The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

IMF comes late to the party but then cannot quite admit it

In an early blog post – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy (October 15, 2009) – I outlined prior research that I had done on the issue of inflation targetting (IT). In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – we provided further analysis on the issue. We found that there was no significant difference in inflation and output dynamics between IT and non-IT nations. This was consistent with the evidence from other studies. Mainstream economists continually claim that IT delivers a range of virtues and central banks that implement IT use interest rates hikes aggressively when there is a hint of price pressure emerging. The latest evidence from an IMF study is that there was no significant difference between IT and non-IT nations in the recent inflationary episode. The research exposes IT for what it is – an article of ideological faith rather than an evidence-based and responsible policy approach.

When central banks, infested with Milton Friedman’s Monetarist ideas, tried to implement them in the form of monetary targetting – that is, attempting to set limits on the growth of the money supply, they soon found out that they had little control over the growth.

This was a period when inflation was accelerating largely due to the OPEC oil price hikes in October 1973 and the subsequent distributional struggle between capital and labour as to who would take the real income loss arising from the more expensive oil imports.

The UK went early to the party, even before the inflation had emerged, when in 1971 it introduced its – Competition and Credit Control (CCC) – policy, which saw the Bank of England use open market operations (liquidity management measures) to control the money supply.

By 1973, the Bank acknowledged total failure and the policy was scrapped.

Other central banks didn’t heed the lesson and tried to conduct monetary policy by controlling the growth of the money supply.

Many OECD countries didn’t heed the lesson and explicitly adopted monetary targeting as their monetary policy framework, including the US, Australia, and Canada.

They were completely dominated by the Friedman resurrection of the old Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) which sourced the accelerating inflation in the growth of the money supply.

That theory had been completely discredited during the Great Depression by the work of John Maynard Keynes and his colleagues but somehow made a comeback in the 1970s.

As a result the central banks thought they could control inflation via monetary targetting.

The aim was to automate monetary policy by forcing the money supply to follow some long-run real output growth path.

If this trend growth rate was 4 per cent per annum, and a 2 per cent inflation rate was desired, then the monetary growth target would be set at 6 per cent per annum.

The claim was that maintenance of that growth volume would result in stable macroeconomic conditions.

The erroneous assumptions underlying this experiment were that the monetary authorities actually had control over the money supply and that there was a solid connection between the volume of money and nominal gross domestic product (that is, velocity was stable and predictable).

These assumptions were simply assertions derived from the QTM.

The monetary targeting experiment during the 1980s failed everywhere as measured velocity proved to be highly volatile, as different measures of money moved in different ways and as commercial banks and other financial intermediaries innovated around regulations imposed by the monetary authorities.

Like the UK, other nations also found out that such an approach could not achieve the aim and that the money supply growth rate was not something that the central bank could just set as an achievable policy outcome.

Suffice to say that the progressive economists (Post Keynesians, etc) had long shown that the money supply was an endogenous outcome driven by the demand for loans from businesses and households.

The banking system would respond to that demand by issuing loans (loans create deposits), which would see the money supply grow.

The central bank could do little to constrain that activity.

These insights, in turn, revealed that the mainstream depiction of the banking system – where banks are just intermediaries who accumulate reserves which then allows them to make loans – was completely at odds with the reality of the system it sought to explain.

The reality is that banks make loans independent of their reserve holdings and then worry about reserve management separately.

By the early 1990s, it was apparent that the monetary targetting approach – and Milton Friedman’s main ideas – were inapplicable to modern monetary economies.

One wonders how the Monetarists were able to maintain credibility in the face of the total failure of their fundamental ideas.

But Groupthink does not honour empirical credentials, which is a separate story that I won’t discuss here.

As a consequence of the failure of monetary targeting, monetary authorities in many OECD countries reconstructed their approach to monetary policy during the 1990s by introducing regimes that targeted the inflation rate directly – or, similarly, regimes that placed a large and explicit emphasis on inflation.

What are the main arguments made by the proponents of inflation targeting and the alleged benefits of the monetary policy framework?

In our 2008 book (cited above) we characterised the shift to inflation targeting as the triumph of the NAIRU ideology.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand adopted inflation targeting first in 1990.

This is no surprise given the country had been undergoing a vast neo-liberal unwinding of its Keynesian Welfare State since the mid-1980s.

Canada was next to formally announce inflation targeting guidelines in February 1991 then Israel in December 1991, followed by the United Kingdom in 1992, Sweden and Finland in 1993.

Australia and Spain followed in 1994.

Inflation targeting refers to a monetary policy framework where the central bank explicitly and publicly declares a target inflation (or price) quantum and changes short term interest rates to manipulate economic activity (and inflationary expectations) in order to maintain actual inflation within the pre announced target, which may be represented by an acceptable range.

The strong focus on maintaining a low and stable inflation was consistent with the belief in a NAIRU view of the world, whereby there is some unique real level of activity (summarised in either output or employment) that the economy gravitates to, and any episodes of price disinflation will only temporarily push the real economy below these levels.

The move to inflation targeting, be it formally announced or more pragmatically implemented, reflecting an overwhelming faith in NAIRU ideology, marked the final stages in the abandonment of full employment in OECD countries.

The modern policy framework is in contradistinction to the practice of governments in the Post World War II period to 1975 which sought to maintain levels of demand using a range of fiscal and monetary measures that were sufficient to ensure that full employment was achieved.

Over this period – the Keynesian era of full employment, unemployment rates were usually below 2 per cent.

Since the mid-1980s unemployment rates in most OECD countries were usually above 6 per cent

More recently, underemployment has become a serious issue as labour markets are casualised and demand for labour suppressed.

Inflation targeting proponents claim that it has several advantages over previous monetary policy approaches.

Many of the gains are attributed to the fact that inflation targeting allegedly provides the central bank with the independence it needs to be credible, transparent and accountable – essential conditions for an effective policy regime.

The enhanced policy credibility allegedly allows a higher sustainable growth rate.

The enhanced central bank independence allegedly overcomes the time inconsistency problem whereby an inflation bias is generated by the pressure the elected government places (implicitly or explicitly) on non elected officials in the central banks to achieve popular outcomes.

Thus inflation targeting can allegedly lock in a low inflation environment.

There were also claims that inflation targeting not only reduces inflation variability but also reduces the variance of output growth.

If certainty in monetary policy generates more stable nominal values, it is argued that lower interest rates and reduced risk premiums follow.

This allegedly stimulates higher real growth rates via an enhanced investment climate.

Further, inflation persistence is allegedly reduced because one time shocks to the inflation rate are quickly eliminated by the policy coherence.

It was claimed that the reduced inflation variability allows more certainty in nominal contracting with less need for frequent wage and price adjustments.

This in turn means less need for indexation and short-term contracts.

However, the implications of this are a flatter short-run Phillips curve.

In other words, higher disinflation costs – more unemployment and real GDP losses.

How large are the output losses following discretionary disinflation?

Can these output losses be attenuated by the design of the monetary policy?

The conservatives argue that the losses are minimised if the disinflation is rapid.

But the credible research literature shows that the losses are inversely related to the speed of disinflation.

There has also been no credible empirical research which shows that a more politically independent central bank can engineer disinflations with attenuated real output losses.

The evidence is that while inflation targeting does not generate significant improvements in the real performance of the economy, the ideology that accompanies inflation targeting does damage to the real economy because it embraces a bias towards passive fiscal policy which locks in persistently high levels of labour underutilisation.

Disinflationary monetary policy and tight fiscal policy can bring inflation down and stabilise it but it does so at the expense of creating and maintaining a buffer stock of unemployment.

The policy approach is seemingly incapable of achieving both price stability and full employment.

An examination of the research literature that followed the introduction of this approach suggests that inflation targeting has not been effective in achieving its aims.

The most comprehensive and rigorous work on the impact of inflation targeting is the 2003 study by Ball and Sheridan who aimed to measure the effects of inflation targeting on macroeconomic performance in 20 OECD economies, of which seven adopted inflation targeting in the 1990s.

They used special econometric techniques (which are widely accepted) to compare nations that had adopted targeting to those that had not.

Overall, Ball and Sheridan found that inflation targeting does not deliver superior economic outcomes (mean inflation, inflation variability, real output variability, long-term interest rates).

One of the claims made for inflation targeting is that central bank independence and the alleged credibility bonus that this brings should encourage faster adjustment of inflationary expectations to the policy announcements.

Ball and Sheridan found that there is no evidence that targeting affects inflation behaviour in this regard.

Here is a link to – The problem with inflation targeting – which is a 2004 Working Paper version which you can get for free – (it was subsequently published elsewhere).

We found similar results for Australia with the degree of persistence in the inflation rate being unaffected by the transition to inflation targeting in 1994.

A related perceived benefit of inflation targeting is that it expunges inflationary expectations from the economy.

There is virtually no research in this area which uses survey data on expectations from consumers, and only little research which uses forecaster’s data.

In our 2004 study we found that, among other things, the major mean-shift in inflation and inflationary expectations occurred during the 1991-2 recession and had nothing at all to do with the onset of inflation targeting (1994).

In fact, there were no inflationary pressures in the economy (apart from a brief period in early 2000 when a 10 per cent value added tax was introduced for the first time) after the 1991-2 recession.

For Australia, at least, it is hard to attribute the lower inflation in the 1990s and beyond to the conduct of inflation targeting at all.

The decline in the inflation juggernaut occurred around the 1991 recession in most countries.

So there was no hard evidence available to support the rhetoric of the proponents of inflation targeting.

Considered in isolation, inflation targeting does not appear to make much difference.

It is certainly hard to distinguish it from non-inflation targeting countries.

But the real damage comes from the discretionary fiscal drag which is the ideological partner to inflation targeting.

Economists use a concept called the sacrifice ratio as a standard measure of the costs of disinflation.

The sacrifice ratio shows the percentage cumulative loss of real output divided by the cumulative reduction in the inflation rate over the disinflation period.

Thus, a sacrifice ratio of three implies that a one-point reduction in the trend inflation rate is associated with a loss equivalent to 3 per cent of initial output.

There is a vast literature on the estimation of sacrifice ratios which typically find that disinflations are not costless and, are in fact, significant.

Our 2004 study calculated three measures of the sacrifice ratio for eight countries over country-specific episodes.

The findings were consistent with other research.

Of note, is the finding that the average estimated GDP sacrifice ratios have increased over time in Australia, from 0.6 in the 1970s to 1.9 in the 1980s and to 3.4 in the 1990’s.

That is, on average reducing trend inflation by one percentage point results in a 3.4 per cent cumulative loss in real GDP in the 1990s.

The IMF comes late to the party

For years, the IMF pushed the inflation targetting line hard as part of its role as a global neoliberal attack dog.

In doing so, it ignored the research evidence to the contrary.

Well, it seems to finally be acknowledging that the approach has not fulfilled its promises.

In a recent IMF Working Paper No. 2025/212 (published October 24, 2025) – Navigating the 2022 Inflation Surge – the authors find:

… that (de jure) IT frameworks did not systematically deliver better inflation outcomes during this episode. The decline in inflation back towards historical norms was broadly comparable across (de jure) IT and non-IT country groups.

The important point that I made repeatedly from 2021 onwards as central banks started to hike interest rates was that the inflationary episode that followed COVID-19 and the Ukraine invasion was not driven by excess spending.

Central banks around the world (bar Japan) all claimed that they had to hike rates to suppress aggregate spending but failed to acknowledge that the pressures were all supply-oriented and that the major drivers were not at all sensitive to interest rate changes.

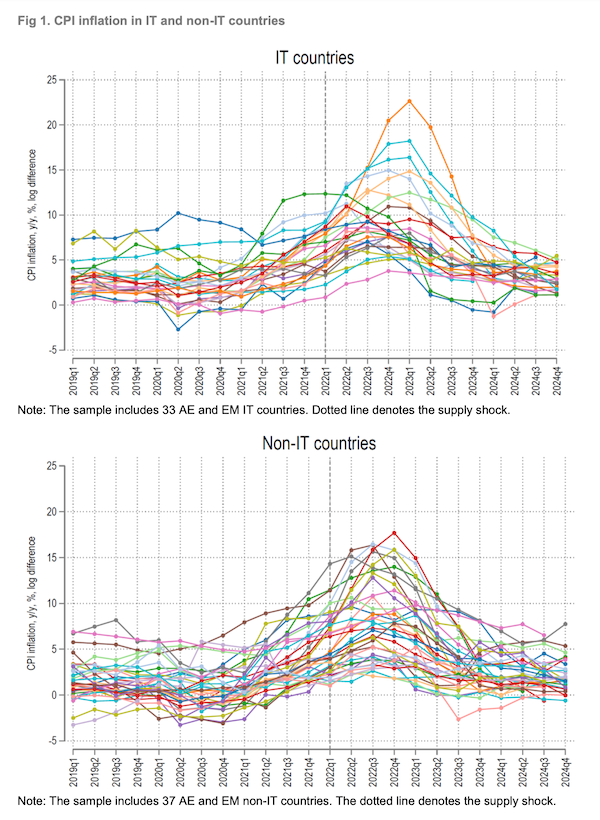

The IMF compared the performance of “33 advanced and emerging market IT countries and 37 non-IT peers” over the period following 2022.

They found:

Despite stronger institutional signaling, IT central banks did not consistently achieve better inflation outcomes than their non-IT peers. Inflation expectations were not more firmly anchored, real economic costs were not unambiguously lower, and although IT central banks were somewhat more proactive, their policy stance did not produce significantly different macroeconomic results. These findings point to a disconnect between the theoretical promise of IT and its practical effectiveness in navigating supply-side shocks.

Who would have thought?

The findings also support the view I expressed that the central banks should not have hiked interest rates in the face of supply-side inflationary pressures.

The IMF researchers found that:

These findings underscore a broader vulnerability of IT when inflation is driven by geopolitical events, climate shocks, or structural supply constraints. In such settings, the relationships embedded in standard forecasting models shift rapidly, pass-through becomes highly state-dependent, and projection errors widen, undermining the role of baseline forecasts in policy calibration. The 2022 post-invasion surge, dominated by energy and food prices, illustrated these limits.

In other words, the IT consensus is not fit for purpose (and never was).

They also admit that:

The credibility case for IT is also less persuasive under persistent supply shocks.

In other words, central banks lose their authority when they needlessly hike rates and damage the well-being of mortgage holders.

This graph shows that “the difference in inflation trajectories between IT and non-IT countries was not statistically significant”.

So the IMF’s position is that IT does work but not when inflation is being driven by supply-side factors.

First, the evidence reported above does not support the faith in IT.

Second, the inflationary episodes of any significance over the last 5 decades have been supply-side events.

The period of extended austerity and the abandonment of full employment (and the attacks on trade unions) have all combined to render excess demand events virtually extinct.

Interestingly, the IMF found that:

… IT countries, on average, experienced about 1.5 percentage points higher inflation than their non-IT counterparts throughout the sample period. While the inflation gap has remained broadly unchanged immediately after the shock, a divergence re-emerged after 2023. Inflation declined more sharply in non-IT countries, widening the difference once again.

They are at wits end to explain that while trying to hold onto the faith that IT still works.

The evidence that I have found in examining this period is that the IT countries which hiked the most actually caused the supply-side inflationary pressures to worsen.

MMT economists point to factors such as increased business costs in concentrated markets being passed on to consumers and in Australia, for example, it was obvious that the RBA hikes were being passed on by landlords in the form of higher rents.

Even as the supply-side factors abated, the rent component of the CPI in Australia was still driving the inflation rate – courtesy of the RBA interest rate hikes.

These impacts help explain why the inflation was higher in IT nations compared to non-IT nations.

The IMF is silent on this obvious causation.

The other IMF finding is that there was no difference in measured inflationary expectations between IT and non-IT nations – “inflation expectations held steady in both IT and non-IT countries”:

The main takeaway is that IT central banks have not offered any edge in stabilizing short-term expectations and the gap between IT and non-IT central banks is surprisingly narrow. At longer horizons, the difference is negligible. Simply put, IT did not deliver a decisive advantage when it came to anchoring inflation expectations during this supply-side inflation shock

Which puts a sword through the narratives that the likes of the RBA kept using to justify continuing to hike interest rates even though inflation was already falling.

They kept claiming that expectations would ‘break out’ and become a separate problem.

No such evidence – nor was there in 2022 or 2023 when the hiking was going on.

It was a sham cover to justify the unjustifiable.

A final point is that the IMF research found that the IT nations were more aggressive in pushing up interest rates:

This raises a question if IT central banks delivered more forceful tightening without achieving better results, what exactly was gained?

They don’t really answer that question.

But I can.

A massive redistribution of income from low-income mortgage households to high-income financial asset holders occurred.

That is what the central banks actions achieved.

The other findings relate to exchange rate volatility and output volatility – no discernible IT superiority.

Conclusion

While these results should be another nail in the neoliberal coffin – they won’t be.

IT and all that goes with it is an article of faith – not an empirically-grounded and justified approach.

So they will persist with it despite the evidence that it doesn’t live up to its claims (by some margin).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill this article seems rushed. It’s evident with tenses used.

Was link to Ball’s & Sheridan 2003 working paper meant to be included? -> https://www.nber.org/papers/w9577 . Your 2004 article is also missing and one has to dig it from archiving sites -> https://web.archive.org/web/20050131224945/https://e1.newcastle.edu.au/coffee/pubs/wp/2004/04-04.pdf

Regards,

Adrian Teri

I was left puzzled by this statement: “Second, the inflationary episodes of any significance over the last 5 decades have been supply-side events.”

I would not have thought that this describes the inflation in the UK in the 1970s which led to the election of Thatcher. I would have thought this inflation was cost push inflation.

In this context there’s an interesting article here: https://labouraffairs.com/2025/09/01/the-significance-of-the-rejection-of-bullock-by-the-trade-unions/

Main 70s inflation event was OPEC embargo, so supply driven. Following this, highly unionised workforces fought for compensating wage rises.

Bill covers this in the post, which is clear and strong.

Can anyone credibly argue with this succinct summary of recent economic history on this topic:

“The period of extended austerity and the abandonment of full employment (and the attacks on trade unions) have all combined to render excess demand events virtually extinct.”