Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – June 5-6, 2021 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Central bankers are talking about retaining quantitative easing to ease the aggregate demand losses associated with the implementation of withdrawal of fiscal stimulus programs. If calibrated correctly, QE can replace the net financial assets destroyed by the withdrawal of the fiscal injection.

The answer is False.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt.

So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves.

So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank).

The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for ‘long maturity’ assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve.

These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates.

This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop.

But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Question 2:

If the growth in wages (the money you get paid) keeps pace with inflation which is accelerating at the same rate as labour productivity is growing then the wage share in GDP remains constant.

The answer is True.

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP. Economists differentiate between nominal GDP ($GDP), which is total output produced at market prices and real GDP (GDP), which is the actual physical equivalent of the nominal GDP. We will come back to that distinction soon.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. Stocks (L) become flows if it is multiplied by a flow variable (W). So the wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period.

So the wage bill = W.L

The wage share is just the total labour costs expressed as a proportion of $GDP – (W.L)/$GDP in nominal terms, usually expressed as a percentage. We can actually break this down further.

Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP per person employed per period. Using the symbols already defined this can be written as:

LP = GDP/L

so it tells us what real output (GDP) each labour unit that is added to production produces on average.

We can also define another term that is regularly used in the media – the real wage – which is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

We might consider the aggregate price level to be measured by the consumer price index (CPI) although there are huge debates about that. But in a sense, this macroeconomic price level doesn’t exist but represents some abstract measure of the general movement in all prices in the economy.

Macroeconomics is hard to learn because it involves these abstract variables that are never observed – like the price level, like “the interest rate” etc. They are just stylisations of the general tendency of all the different prices and interest rates.

Now the nominal wage (W) – that is paid by employers to workers is determined in the labour market – by the contract of employment between the worker and the employer. The price level (P) is determined in the goods market – by the interaction of total supply of output and aggregate demand for that output although there are complex models of firm price setting that use cost-plus mark-up formulas with demand just determining volume sold. We shouldn’t get into those debates here.

The inflation rate is just the continuous growth in the price level (P). A once-off adjustment in the price level is not considered by economists to constitute inflation.

So the real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command and is obviously influenced by the level of W and the price level. For a given W, the lower is P the greater the purchasing power of the nominal wage and so the higher is the real wage (w).

We write the real wage (w) as W/P. So if W = 10 and P = 1, then the real wage (w) = 10 meaning that the current wage will buy 10 units of real output. If P rose to 2 then w = 5, meaning the real wage was now cut by one-half.

Nominal GDP ($GDP) can be written as P.GDP, where the P values the real physical output.

Now if you put of these concepts together you get an interesting framework. To help you follow the logic here are the terms developed and be careful not to confuse $GDP (nominal) with GDP (real):

- Wage share = (W.L)/$GDP

- Nominal GDP: $GDP = P.GDP

- Labour productivity: LP = GDP/L

- Real wage: w = W/P

By substituting the expression for Nominal GDP into the wage share measure we get:

Wage share = (W.L)/P.GDP

In this area of economics, we often look for alternative way to write this expression – it maintains the equivalence (that is, obeys all the rules of algebra) but presents the expression (in this case the wage share) in a different “view”.

So we can write as an equivalent:

Wage share – (W/P).(L/GDP)

Now if you note that (L/GDP) is the inverse (reciprocal) of the labour productivity term (GDP/L). We can use another rule of algebra (reversing the invert and multiply rule) to rewrite this expression again in a more interpretable fashion.

So an equivalent but more convenient measure of the wage share is:

Wage share = (W/P)/(GDP/L) – that is, the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (GDP/L).

I won’t show this but I could also express this in growth terms such that if the growth in the real wage equals labour productivity growth the wage share is constant. The algebra is simple but we have done enough of that already.

That journey might have seemed difficult to non-economists (or those not well-versed in algebra) but it produces a very easy to understand formula for the wage share.

Two other points to note. The wage share is also equivalent to the real unit labour cost (RULC) measures that Treasuries and central banks use to describe trends in costs within the economy. Please read my blog – Saturday Quiz – May 15, 2010 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on this point.

Now it becomes obvious that if the nominal wage (W) and the price level (P) are growing at the pace the real wage is constant. And if the real wage is growing at the same rate as labour productivity, then both terms in the wage share ratio are equal and so the wage share is constant.

The wage share was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this constancy was so marked that Kaldor (the Cambridge economist) termed it one of the great “stylised” facts. So real wages grew in line with

productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

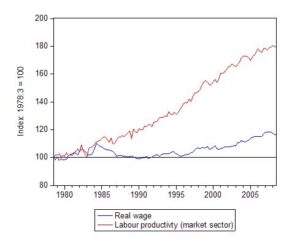

In this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I provided these graphs. First, the movement real wages and labour productivity since 1979. Both series are indexed to 100 as at the September quarter 1978. So by September 2008, the real wage index had climbed to 116.7 (that is, around 15 per cent growth in just over 12 years) but the labour productivity index was 179.1.

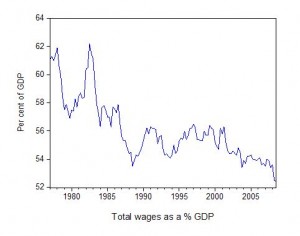

This suggests from our discussion that the wage share should have fallen. That is what the next graph depicts – it shows how far the wage share has fallen in Australia over the last two decades. The trend has been common across the globe during the neo-liberal years and is one of the pre-conditions that explain our current economic crisis.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

Question 3

The government is attempting to stimulate the economy via an expansion in the fiscal deficit. The private market orientated advisors tell them to cut taxes and “privatise” the expansion whereas the more civic-minded advisers argue that there is a need for improved public infrastructure which requires increases in government spending. So imagine that the government is choosing between a tax cut that will reduce tax revenue at the current level of national income by $x and a spending increase of $x. Which policy option will have the greater initial impact on aggregate demand?

(a) Tax cut

(b) Spending increase

(c) Both will be equivalent

(d) There is not enough information to answer this question

The answer is Spending increase.

The question is only seeking an understanding of the initial injection into the spending stream rather than the fully exhausted multiplied expansion of national income that will result.

It is clear that the tax cut approach will have two effects: (a) some initial demand stimulus; and (b) it increases the value of the multiplier, other things equal.

We are only interested in the first effect rather than the total effect.

But I will give you some insight also into what the two components of the tax result might imply overall when compared to the stimulus motivated by an increase in government spending.

To give you a concrete example which will consolidate the understanding of what happens, imagine that the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income is 0.8 and there is only one tax rate set at 0.20.

So for every extra dollar that the economy produces the government taxes 20 cents leaving 80 cents in disposable income.

In turn, households then consume 0.8 of this 80 cents which means an injection of 64 cents goes into aggregate demand which them multiplies as the initial spending creates income which, in turn, generates more spending and so on.

Government spending increase

An increase in government spending (say of $1000) is what we call an exogenous injection into the spending stream and stimulates aggregate demand by that amount. So it might be an order of $1000 worth of gadget X which advances human welfare immeasurably!

The firm that produces gadget X thus increases production of the good or service by the rise in orders ($1000) and as a result incomes of the productive factors rises by $1000.

So the initial rise in aggregate demand is $1000.

This initial increase in national output and income then stimulates (induces) further consumption by 64 cents in the dollar so in Period 2, aggregate demand increases by $640.

Output and income rises by the same amount to meet this increase in spending.

In Period 3, aggregate demand rises by 0.8 x 0.8 x $640 and so on.

The induced spending increase gets smaller and smaller because some of each round of income increase is taxed away, some goes to imports and some is saved.

Tax-cut induced stimulus

The stimulus coming from a tax-cut does not directly impact on the spending stream in the same way as the rise in government spending.

First, imagine the government worked out a tax cut that would increase its initial fiscal deficit by the same amount as would have been the case if it had increased government spending (so in our example, $1000).

In other words, disposable income at each level of GDP rises initially by $1000. What happens next?

Some of the disposable income is saved (20 cents in each dollar that disposable income increases). So immediately some of the tax increase is lost from the spending stream.

In this case the injection into aggregate demand is $800 rather than $1000 in the case of the increase in government spending.

What happens next depends on the parameters of the macroeconomic system.

The multiplied rise in national income may be higher or lower depending on these parameters.

But it will never be the case that an initial fiscal equivalent tax cut will be more stimulatory than a government spending increase.

You may wish to read the following blog posts for more information:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well I’m really going to have to examine the answer for question 2 because straight away I am thinking that if my wages are keeping pace with inflation I may be maintaining a same share of GDP. But if I am also at the same time producing more with my labor but only getting the increase in line with inflation there is more nominal GDP out there because of inflation AND there is more GDP on top of that because I am so much more productive. But you’re only giving me the inflation part so my percentage of total GDP is declining because someone else is getting the productivity part. I will have to review all the equations in the answer when I am not so sleepy. But I can’t really see how I am wrong at this point. But then it has happened that I have been wrong other times.

Well maybe if inflation and my productivity both grew at 0% the answer makes sense.

Alright, so I am not so sleepy now. So I have ten workers who work 100 hours and I pay them $10 an hour and they produce 10 cars for me that I sell for $2000 each. Total GDP- $20,000, total wages $10,000 labor share of GDP-50%

Then there is inflation of 10%, and my workers increase their productivity 10% and I pay them 10% more to keep up with inflation. So now I have ten workers who work 100 hours and I pay them $11 an hour. But they make 11 cars for me that I sell for $2200 each.

Total NGDP is $24,200. Total wages are $11,000. Labor share has dropped to 45.4% of GDP.

Would I be wrong to calculate things this way rather than with all the algebra and formulas in the answer given? Why does my answer conflict with your answer?

Bill,

“If the growth in wages (the money you get paid) keeps pace with inflation which is accelerating at the same rate as labour productivity is growing then the wage share in GDP remains constant.”

I think this question is ambiguous and can be interpreted in two different ways. 1) All variables grow at the same rate and in this case, as you’ve shown, the wage share remains the same and the answer is T. 2) Real wages stay the same but productivity rises at the same rate as money wage and inflation and in this case the answer is F, because now only the denominator rises in the ratio (W/P)/(Y/L).

Also, I would like to indicate that using GDP for nominal product and Y for real product contributes to algebraic exposition clarity.

Best regards!

Jerry,

I think your example is excellent and it shows in a simple way that when labor is deprived of all productivity gains, as it happened during the last half century, real wages stagnate. On the other hand, algebra adds clarification and makes the analysis more general. In your example every bit of extra productivity is captured by the capitalist class and nothing goes to labor. However, if you adjust labor remuneration to reflect productivity gain, the the share of labor remains constant. Conclusion: capitalism in essence is a struggle between the two classes over the distribution of income!

Thank you Demetrios. In my example, the workers are technically no worse off than they were before, but the capitalist (me) is better off. Well actually, if the increase in productivity was because they had to work harder then they are worse off. At least the hours at the imaginary Jerry Brown car company are not very demanding even if the wages are low.

But question 2 was not ambiguous about what it asked. The answer did not follow from the stated conditions. The most important thing is that just possibly Bill will admit I was right just once on one of these quiz questions and then I will be able to die a happy man- just not anytime soon hopefully. I figure with your support the odds of that happening have improved to about one in a hundred 🙂

Jerry, in your example the answer conflicts with Bill’s because you interpreted the question according to my (2) reading. That is, all productivity gain is confiscated by the bloody capitalist, or in Marxian terms more surplus value is extracted from the proletariat. And workers are naturally worst off in “relative” terms, to use a favorite approach of neoclassicalism.

Cheers!

Hi yes. I too am a bit confused. I did a scenario similar to Jerry’s and I found that the real wage workers get can stay the same as nominal wages keep pace with inflation but the overall wage share go down as the bosses get the productivity increase that is accelerating at the same rate as inflation.

What am I not getting?

“What am I not getting?” cs- what you are not getting is a share of the increase in your productivity- the owner is getting that. You read the question the same way I did and I obviously think you were right to read it that way.

Hi yes, from my simple model it seems to me for the wage share to remain constant if say inflation is 10% and productivity increase is 10% is for nominal wages to go up 20% – to cover both inflation (so you can still buy what you used to be able to buy) and the increased amount of stuff being produced (so you get a share of that too).

In Jerry’s example the wage bill adjusted only for 10% inflation becomes W=10,000*1.1=11,000, and real wage (W/P) stays the same.

If the real wage is further adjusted for 10% productivity increase, it becomes W’=11,000*1.1=12,100, which is exactly 50% of new GDP of 24,200.

Therefore, labor share stays the same!

At first I came up with the same answer as Jerry, but reading through Bill’s answer I think we both made the assumption that real GDP increases as a result of productivity… but the question doesn’t say that. In Jerry’s example, the factory should still make ten cars. So wage share stays the same… but hours worked decreases i.e. unemployment increases.

ce

To be precise, in order for the wage share to remain constant the nominal wage must increase by 21%, because of the interaction effect between productivity and inflation (1.1^2).

SomeGuyOnTheInternet

Labor productivity is defined as increase in output per unit of labor, that is LP = GDP/L in Bill’s formulae. Looked from a different angle, productivity shifts down the ATC curve creating a competitive advantage for the firm and assuming that the extra output is absorbed in the market more will be produced instead of laying-off workers. After all, one of the reasons firms invest in new techniques is to reduce cost.

Having said that, I agree with Jerry’s version.

The real question, however, is who reaps the benefits of productivity; the wage share will remain the same only if the entire productivity gain is enjoyed by workers, otherwise it will decrease. And, this is where I spotted the ambiguity of the question. It doesn’t explicitly make clear who benefits from productivity gain.

SomeGuyOnTI

Labor productivity is defined as increase in output per unit of labor, that is LP = GDP/L in Bill’s formulae. Looked from a different angle, productivity shifts down the ATC curve creating a competitive advantage for the firm and assuming that the extra output is absorbed in the market more will be produced instead of laying-off workers. After all, one of the reasons firms invest in new techniques is to reduce cost.

Having said that, I agree with Jerry’s version.

However, the issue is who reaps the benefits of productivity; the wage share will remain the same only if the entire productivity gain is enjoyed by workers, otherwise it will decrease. And, this is where I spotted the ambiguity of the question. It doesn’t explicitly make clear who benefits from productivity gain.

OK I’ve changed my mind I think Jerry is right. Even if real GDP stays the same (as I suggested), the numbers don’t work.

The key paragraph from the solution is this:

“Now it becomes obvious that if the nominal wage (W) and the price level (P) are growing at the pace the real wage is constant. And if the real wage is growing at the same rate as labour productivity, then both terms in the wage share ratio are equal and so the wage share is constant.”

How can the real wage be simultaneously a) constant and b) increasing at the same rate as labour productivity?

I think the key lesson Bill is trying to get across is that unless real wages grow at the same pace as labour productivity, then the wage share decreases. Which I expect we all would agree with.

@ Bill,

Q2 is trickier to answer than it might be, IMO, because of the use words ‘growing’ and ‘acceleration’. I would take ‘accelerating’ to mean that if inflation was 5% one year and 6% the year after, then 7% the year after that etc, then the acceleration would be 1% pa pa.

Then 1% would equal the rate of increase of labour productivity ???

Or in mathematical terms, inflation is the first derivative against time wrt prices whereas its acceleration is the second derivative.

So, tbh, I don’t really understand the question.

Oh well. I guess Bill won’t admit I might be right even once. On a positive note- maybe that’s because he doesn’t want me to die anytime soon… But I’m giving myself full credit for my answer to question 2 in light of my explanation and in the absence of the teacher explaining why I am wrong. So there.