It is a public holiday in Australia today celebrating our national day - the day…

Rounding off the Masterclass in London last weekend

Last Saturday, I held an MMT Masterclass or Teach-In in London. It was an experimental session because I wanted to see what level of difficulty people would find useful as we work on developing the pedagogy and materials for MMTed, which is intending to provide free teaching resources for those interested to learning Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) from first principles. Given the time constraints, I didn’t quite finish Module 1. So I thought I would provide the slides here with a written explanation of what I would have said so that you get the complete context and application of the concepts that we developed together during the class. So this blog post completes the lecture. Thanks to all those who attended and to those who have sent me the requested feedback. This will help us improve the material and presentation approach.

Rounding up the Masterclass in London last weekend

Given the time constraints, I didn’t quite finish Module 1. So I thought I would provide the slides here with a written explanation of what I would have said so that you get the complete context and application of the concepts that we developed together during the class.

I had reached a point where we understood the following relation, which we derived sequentially from the basic National Accounts framework.

At this stage all we had done was manipulate accounting statements, which are true by definition but only take us so far.

As I have said previously, if that was all there was to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) then we would not have much to say at all.

Please read my blog post – Understanding what the T in MMT involves (September 20, 2018) – for more discussion on this point.

We had also found that a macroeconomic equilibrium (or ‘steady-state’) was reached when there were no forces present to change the current level of output and income.

I made it clear that this state was not necessarily associated with ‘market clearing’ (that is, full employment) and that the Capitalist monetary system as a result of the decentralised nature of spending decisions has a propensity to be at rest with mass unemployment.

This was the point that Keynes made in the 1930s and was the reason he considered the system needed ‘exogenous’ spending injections needed to disturb the ‘rest’ if there was an under-full employment equilibrium.

In terms of the expenditure-income flow model we developed (the slide with all the arrows going everywhere), we defined the equilibrium, where the GDP flow is constant to be where total leakages (T + S + M) from the expenditure-income system were equal to the total injections (G + I + X).

That knowledge allowed us to develop and explicated the expenditure multiplier, which is a central concept in macroeconomics.

So, this is the last part of the Module, that I was unable to finish in London.

The question then arises: What happens if the equilibrium is disturbed?

We already saw in our expenditure multiplier simulation, what happened as the initial increase in one of the injections, in that example, government spending, as the economy responded to the increased aggregate demand by producing more income and employment, which, in turn, induced additional household consumption expenditure.

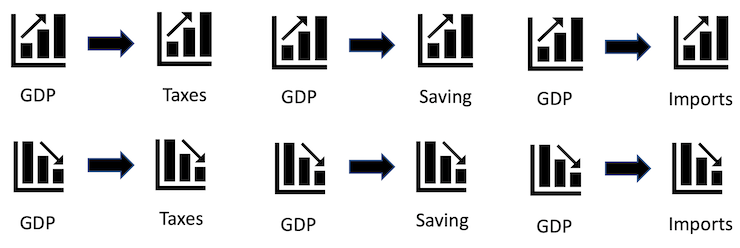

At at each sequence the three leakages rose according to their relation to income changes – saving via the 1 minus the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC), taxes via the tax rate, and imports via the Marginal Propensity to Import (MPM).

Viewed in a differ way, we have the accounting expression for the sectoral balances;

(G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M + FNI)

And we know that:

We also made it clear that the increase in taxes is not because governments have increased the tax rate but arises as a result of more people being in work and companies selling more goods and services, which means the overall tax revenue rises.

In other words, when there is an initial shock arising from a rise (or fall) in the injections (G , I, or X), which leads to a rise (fall) in GDP and national income, the leakages rise (or fall) via the multiplier process and the system eventually comes to rest when the change in the sum of the leakages equals the initial increase (fall) in the spending injection.

So we have moved beyond meagre accounting at this stage.

We need to have behavioural insights about consumers (households) and business firms about their spending behaviours, tax propensities etc to understand the way in which income changes bring forth ‘endogenous’ changes via these conjectured behaviours that eventually restore equilibrium.

In our expenditure multiplier example, we saw how the initial injection of government spending led to a change on equilibrium income that was 79.6 currency units higher than where it started from.

We are now able to appreciate the so-called automatic stabilisers that are present because the fiscal parameters are sensitive to national income changes as discussed above.

The only additional statement to make here is that while we have seen how tax revenue rises and falls with changes in national income, without the tax rate changing at all, government spending, in some jurisdictions, may also rise (fall) with national income changes, except in this case the spending response will be counter-cyclical, whereas the tax sensititivity is pro-cyclical (that is, moves up (down) with the non-government spending cycle).

This is because governments also pay out welfare payments when unemployment rises and vice versa.

Consider the government fiscal balance: (G – T).

We now can see why this cannot be a policy target because it is not fully controlled by government.

Why?

The final fiscal balance is determined by both discretionary fiscal policy settings and the spending decisions of the non-government sector.

I often tell audiences (particularly those in the business community) who indicate they think the fiscal deficits are too large, that if they want to have lower government deficits then they can do something about that themselves – spend more on capital investment and less on financial assets that deliver hardly any value to society and just shuffling existing national income around.

So, in summary, we know that:

1. When economic activity is strong, T rises and G falls which reduces the deficit or increases a surplus (other things equal) depending on where you start from..

2. When economic activity is weak, T falls and G rises which increases the deficit or reduces a surplus (without any policy change).

This cyclical effect is known as automatic stabilisation because they are triggered by the spending cycle and do not require any shift in government fisal policy.

This insight then allows us to understand the difference between the structural and cyclical fiscal balance, which regularly pop up in government resports, statement by the IMF etc.

The structural balance is the balance that would be achieved when the system was full capacity and the leakages from the income-expenditure stream were at their maximum value (as a result of income being maximised).

We discussed in the Masterclass how agencies manipulate the full employment benchmark when they are computing potential GDP and the derivative output gaps.

The same problem arises here because to estimate a structural balance we need to estimate a benchmark level of output that would be coincident with full employment. In other words, the division between the structural balance and the cyclical balance is highly sensitive to how we construct our full employment benchmark.

The IMF tends to define full employment as coinciding which much higher unemployment rates than I consider to be irreducible.

In other words, they produce estimates of the structural deficit that are much higher than I would produce and, as a result, conclude that the economy is at full capacity well before it is truly reached that point.

This has ideological value for them, given they tend to argue against fiscal deficits.

Please read my blog posts for more discussion on this point.

1. The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise (February 27, 2019).

2. The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

3. Why we have to learn about the NAIRU (and reject it) (November 19, 2013).

4. NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy (November 19, 2010).

5. The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 16, 2009).

We are now in a position to derive the MMT fiscal rule, which doesn’t bear any similarity to the types of rules you see coming out of the mainstream economics paradigm.

We have to ask: What is the purpose of fiscal policy?

The answer will never include to achieve some specific fiscal to GDP ratio or to shift to surplus in the medium-term, or any other similar statements.

When considering what is the desirable fiscal stance of government, we have to define the aim of the government, as our agent, to be working to increase well-being and avoid resource wastage.

In that context, the aim of the government should be to achieve GDP commensurate with full employment.

Of course, that GDP should be ecologically sustainable and equitably distributed.

That leads to a broader concept of efficiency than you will find in the mainstream macroeconomics narrative.

Efficiency has to be defined in terms of maximising net social benefit rather than confining the calculation to private benefits and costs.

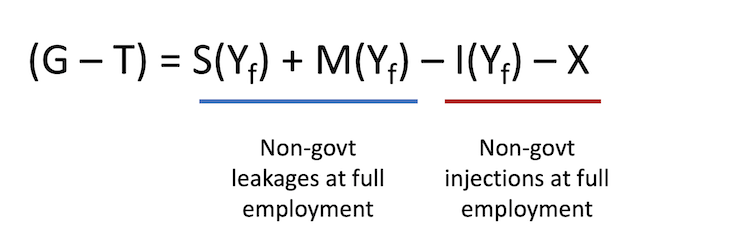

Given that, we can restate our sectoral balance accounting statement to see how we can gain further insights from it.

(G – T) = (S – I) – (CAB)

We know that for national income to be stable, the fiscal deficit has to equal the desired overall saving of the private domestic sector (S – I) minus the current account surplus.

The Right-hand expression is overall non-government saving.

But even though a fiscal deficit of that magnitude will stabilise national income it will not necessarily sustain full employment.

This is another way of stating what we determined previously.

The GDP flow that stabilises when the spending injections equal the spending leakages may not be commensurate with the GDP that will generate enough jobs to satisfy the aspirations of the available labour supply.

Accordingly, to sustain full employment, the condition for stable national income is written more specifically:

Yf is the full employment GDP flow level. So, for example, S(Yf) is the total household saving that would be forthcoming when economic activity is at full employment (capacity).

The only term you will not have encountered is I(Yf) and I didn’t discuss this earlier when I was talking about the leakages and injections. I asserted, for simplicity, that private capital expenditure (I) was an exogenous injection.

The fact that I have now indicated here that it also is sensitive to the strength of economic activity relates to the accelerator theories. I clearly did not have time to advance these notions in Module 1.

I discussed the ‘accelerator’ model of investment in this blog post – Investment and profits ( July 27, 2012).

There is a chapter on this material in our textbook – Macroeconomics.

If the non-government drains are greater than the non-government spending injections at the full employment GDP flow level then for national income to remain stable, there has to be a fiscal deficit (G – T) sufficient to offset that gap in aggregate demand.

In other words, the appropriate fiscal position is determined largely by the non-government spending and saving decisions.

If we spend more and save less, pay less tax or import less, then the fiscal deficit required to sustain full employment will be lower (or the surplus higher) than otherwise.

We should think of the fiscal balance as being whatever it takes to maintain the full employment fiscal condition specified by that equation.

That was where Module 1 would have ended at the London Masterclass.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.