Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Australian fiscal statement 2018-19 – an election stunt, limited economic coherence

The Australian Treasurer brought down the 2018-19 Fiscal Statement (aka Budget) on Tuesday evening with much fanfare. The one message that dominated the cant and hypocrisy was that there will probably be an early election, maybe later this year. The Government is scandal-ridden, is enduring destructive infighting over leadership and policy direction, and has made some monumentally disastrous decisions in the current term of office (for example, denying the need for a Royal Commission into the financial sector, which they were bulldozed into finally accepting, and, which is now revealing massive corruption in our banks and insurance companies). Being so far down in the opinion polls means one thing. They use the annual ‘fiscal’ show to make themselves look good and dollop out (albeit with a lag) some scraps (tax cuts) to the masses, while reserving the huge tax cuts for the top-end-of-town. And, for the first time in as long as I can remember, I didn’t even bother to listen to the Treasurer’s speech. In fact, I could write some text generating code which would generate a ‘Budget Speech’ that was remarkably similar to the Treasurer’s speech. So why waste 30 minutes in the evening listening to it. I would prefer to be sorting socks in my sock draw!

Hypocrisy and ignorance knows no limits when it comes to fiscal matters

I deliberately have avoided listening to the radio much in the last few days because of the hysteria associated with fiscal matters at this time of the year.

Commentators airing their ignorance rampage in the media making out they are hard-edged reporters keeping the politicians honest.

The problem is their questions expose their own stupidity and thus the public is mislead and the narrative becomes so distorted from what is actually going on that a fictional world is created.

When it comes to fiscal matters we live in a fictional world and decisions that are of great importance are made on that basis.

It amazes me actually.

Not so long ago, this conservative government was predicting the sky would fall in because the previous Labor government (masquerading as a progressive party but really as conservative and misguided as the actual conservatives) had increased the fiscal deficit during its tenure through the GFC.

Of course the deficit rose during the GFC. It did so because the government of the day, to its credit, introduced a large and rapid stimulus package which saved Australia from recording a recession – there was a slowdown only.

But even if the government had not have acted in that way, the deficit would have risen as a result of the operation of the automatic stabilisers – slowdown in employment and wages growth leading to a fall in tax revenue and rising net public spending.

So while the current government was railing against deficits and public debt a few years ago to win political favour from the voters, times change and now they no longer mention those issues.

Of course, they are overseeing a rise in tax receipts which has reduced the fiscal deficit as a result of on-going economic growth – below trend but still moderately positive.

They are also benefitting politically from the fact that various mining concessions (writing off investment losses etc) are expiring quickly now and so the corporate sector is being forced to pay more tax.

And the rest of us seem to ride this cycle of hypocrisy – deficits are bad, deficits don’t matter much, etc – and seem to forget what our elected representatives said yesterday.

Just wait a while – and we will be back to the deficits are shockingly dangerous narrative before long.

That is, when it is politically convenient for one or both political parties to push that line.

Thank someone for GetUp!

The Australian public advocacy and campaigning organisation – GetUp! – which is funded by grass roots subscriptions, has introduced a new element to its operations.

It has decided to help in educating the public about macroeconomics, specifically about the work that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists, such as myself have been doing.

I met with the campaign director last year and they are now producing some great videos and material.

Among their “seven key policies” is a “National job guarantee” and a “public banking system”.

On the Job Guarantee, they say (Source):

A Job Guarantee is a federally funded, locally administered initiative to directly end involuntary unemployment and underemployment.9 Anyone who wants to work would be able to accept employment in a publicly funded position at a living wage. Crucially, these jobs would come with all the workplace rights of full-time employment: holiday leave, sick leave, and overtime.

Straight MMT.

These developments are much more important to the development of progressive ideas in Australia than anything the Labor Party opposition is touting these days.

You can see a video where GetUp! further explains why the fiscal debate in Australia is nonsensical – HERE.

The fiscal statement – consider these graphs

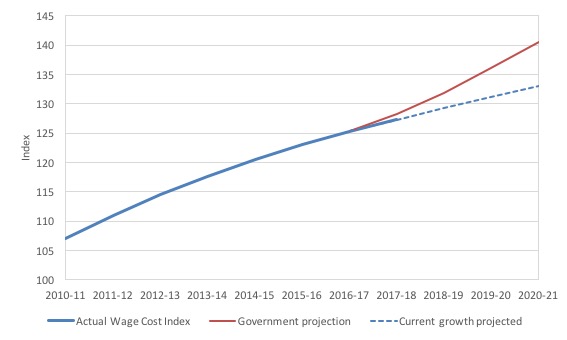

Consider the following graphs. They are two different views of wages growth in Australia, which is now at record lows in relation to the preferred Australian Bureau of Statistics measure the Wage Price Index.

The first graph the actual annual growth (blue bars) since the 1998-99 financial year up until the present period (the 2017-18-17 result is the average of the September and December quarters only). It has been trending down for several years now as the impact of the sustained levels of labour underutilisation take their toll.

The red bars are the estimates and projections in Statement 2: Economic Outlook – published on Tuesday by the Government.

The Government wrote:

Wage growth is forecast to pick up to 2¼ per cent through the year to the June quarter 2018, 2¾ per cent through the year to the June quarter 2019 and 3¼ per cent through the year to the June quarter 2020, as economic growth strengthens to be above its potential rate and excess capacity in the labour market is absorbed.

Note also that the Government is projecting that the unemployment rate is set to remain well above the pre-GFC low (5.25 per cent out to 2018-19) and the participation rate is projected to be constant over the period to 2019-20.

The fiscal estimates make no projections about underemployment, which is a huge problem in Australia now.

Employment growth is projected by the Government rise this year (2017-18) to 2.75 per cent but then drop back to 1.5 per cent per annum for 2018-19 and 2019-20. This is probably realistic.

At present we have:

1. 1107.0 thousand underemployed and taken together with the official unemployed there are 1,841 thousand workers available yet idle. The current broad labour underutilisation rate is 13.9 per cent.

2. With a strong bias towards part-time work, entrenched underemployment, and flat wages growth, it is clear that the Australian economy is not projected to go anywhere near full employment over the projected period of the fiscal aggregates.

So the reasonable question is: Why will the Wage Price Index recover so strongly and so quickly?

The reasonable answer is that it will not – the dynamics are just not going to be there.

The second graph shows the Wage Price Index itself (since 2010-11). The red line is the fiscal projections for the wages growth, while the blue dotted line is a reasonable projection based on recent growth (with no material change in labour market conditions projected).

You can see there is a credibility issue here in terms of a key Government projection.

Why does this matter?

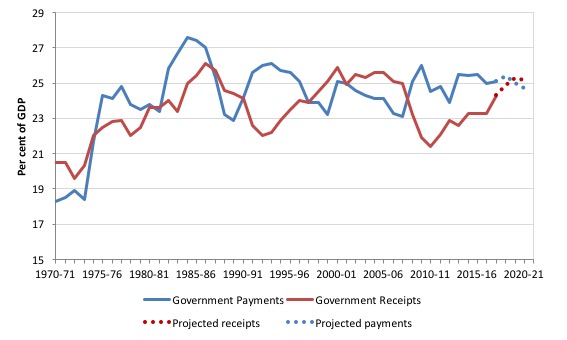

Consider the following graph, which shows government payments and receipts as a percentage of GDP from 1970-71 out to 2021-22

The dotted segments are the fiscal statement projections.

You can see that while payments are projected to stabilise around 25 per cent of GDP, receipts are projected to bolt up from the current 24.3 per cent to 25.5 per cent.

Hence the projected fiscal surplus in 2019-20.

Even though the Government is offering small tax cuts to individuals and larger shifts in company taxation, it is still forecasting solid taxation receipts in the coming years.

This is based on two key projections:

1. The (unbelievable) projected rise in wages growth (as noted above).

2. A massive bounce back in corporate taxation revenue despite the intended cuts in the rate. This is because real GDP growth is forecast to rise from 2.1 per cent in 2016-17 (actual) to 3 per cent per annum by next year.

Will any of that happen? Not likely.

Ridiculous fiscal rules

Some bored economist within Treasury (probably) has wasted his or her time coming up with what the Treasurer is claiming is a new fiscal rule or as he is selling it a “policy speed limit” (Source).

What could that be?

The Treasurer said:

As a Government we have put constraints on how much we spend and how much we tax, to grow our economy and responsibly repair the budget …

We are also keeping taxes under our policy speed limit of 23.9 per cent of GDP set out in our fiscal strategy.

Any fiscal rule that imposes an arbitrary limit like this is not operational.

A future government will either abandon it quickly as it will prove to be unworkable or, if it believes its own narratives, trying to stick to this rule will lead to poor fiscal policies being crafted and implemented.

Think about this scenario:

1. Economic growth booms and tax revenue rises sharply (well above 23.9 per cent of GDP).

2. What is required? Some fiscal tightening – tax increases and/or expenditure cuts.

3. If the government tries to assert the speed limit it will have to cut taxes in this context, exactly the opposite to what a responsible government would do.

4. If it tries to cut spending to slow the economy down unemployment will rise. A poor option as well.

So, either it will be abandoned or dangerous.

Some idiocy has been involved in the construction of that little bit of nonsense.

Tax Cuts

The electioneering in the fiscal statement is clear.

The Government is now offering tax cuts across the board but the detail and subsequent modelling tells us that the cuts are skewed heavily towards high income earners.

Analysis from the NATSEM shows that:

1. “while the government advertised these as payments to low and middle income Australians, most of the benefits would flow through to high income earners in future years.”

2. “a reduced number of tax brackets, and a lower rate of 32.5% to those earning between A$87,001 and A$200,000” – so the degree of progression is being reduced as the tax structure is flattened. Someone earning $A200,000 a year is a very high income earner while someone earning $A87,001 is not.

3. “However this new tax system from 2024-25 is less progressive than the current system. It means higher income inequality – the rich get more of the tax cuts than the poor.”

4. “by 2024-25, the tax cuts means high income earners gain A$7,225 per year, while those earning A$50,000 to A$90,000 gain A$540 per year, and those earning A$30,000 gain A$200 per year”.

5. So a high income earner ($A200,000 pa) gets a tax break 13.4 times what a worker earning $A50,000 will get.

Any notion that the government is sharing out the growth fairly is thus not backed up by the facts.

This is a conservative government bestowing largesse on its key cohort – the top-end-of-town – and pretending it is helping low and middle income earners.

The latter cohort are getting swamped with massive energy cost increases (as a result of ill-conceived privatisations and corporate greed), being ripped off by an obviously corrupt financial sector, and now being dudded by the Government via the flattened tax structure.

The contractionary bias

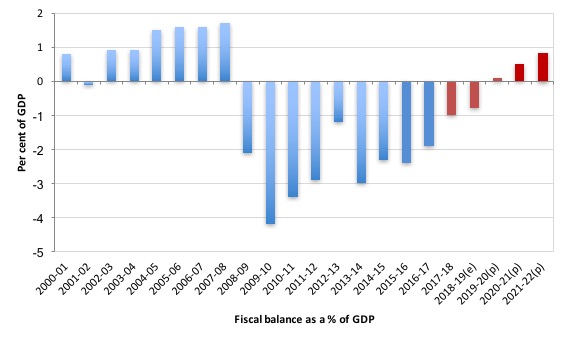

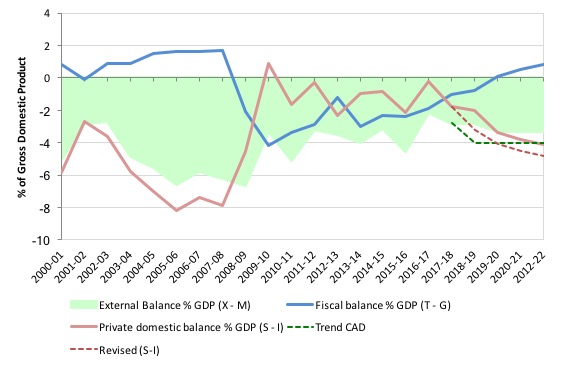

The fiscal statement released last night by the Treasurer has the following forward estimates for the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP. The graph starts in 2000-01 and goes to 2021-22

The red bars are the latest projections from the current Government as outlined in Tuesday’s statement.

The fiscal deficit is projected to fall from $A33,151 million in 2016-17 to $A18,238 million in the current financial year (2017-18). Thereafter, it falls until a surplus of $A2,234 million is projected in 2019-20.

The projected fiscal shift from last financial year is 0.3 points of GDP. The outstanding fiscal deficit is thus estimated to come in at -2.1 per cent of GDP.

The Treasury estimates that the government will reduce its increasingly reduce its contribution to growth in the remaining years of the forecast period until 2020-21, when the fiscal surplus is projected to be 0.5 per cent of GDP.

The fiscal shift from one year to another is the change in the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP changes. It is the result of two factors – the fiscal balance itself (in $As) and the value of nominal GDP (in $As).

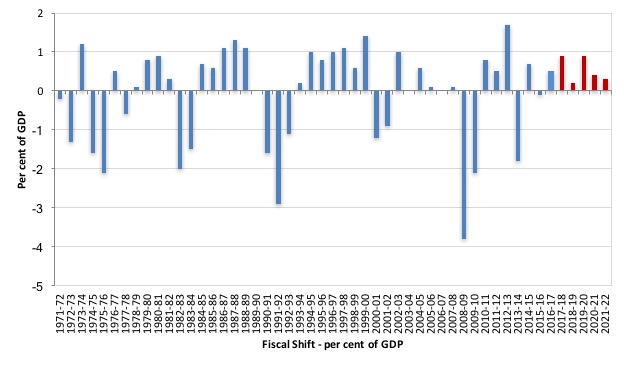

The following graph shows the recent history (from 1970-71) of fiscal shifts.

The biggest fiscal swing in the previous conservative government’s tenure was in the financial year 1999-2000 (a shift of 1.4 per cent).

A sharp slowdown in the economy followed that contraction and the fiscal balance was in deficit two years later (2001-02).

The Australian economy only returned to growth because the Communist Chinese government ran large fiscal deficits themselves as part of their urban and regional development strategy. That spurred demand in our mining sector.

The largest fiscal shift in the sample period shown was the second-last fiscal statement from the previous Labor government in 2012-13 which was equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP. They prematurely withdrew the fiscal stimulus bowing to the assault from the neo-liberal press and commentariat about the dangers of deficits. It was a moronic and damaging retreat.

A major slowdown followed and dented the recovery from the GFC that had been spawned by the fiscal stimulus in the previous two years.

That Labor government was obsessively trying to achieve a fiscal surplus in 2013-14 and was blind to the reality that the private domestic sector was not going to fill the spending gap left by the retrenchment in net government spending.

The result – which was totally predictable – the economy took a nosedive, tax revenue fell even further and the fiscal balance moved further into deficit with unemployment rising.

In Tuesday’s fiscal statement, the forward estimates imply a sharp tightening of fiscal policy (red bars). The fiscal shift in the current year (2017-18) is projected to be 0.5 per cent of GDP, and this increases in the following year (2018-19) to 0.9 per cent of GDP, then 0.2, 0.90 and 0.4 amd 0.3 by 2021-22.

Part of this shift is being driven by the current real GDP growth.

But with record levels of household debt and flat wages growth starting to impact on household consumption spending and business investment still floundering there are real doubts that this level of fiscal drag is desirable.

Unless there is an extraordinary pick up in private spending or net exports then the economy will not achieve the underlying growth assumed and we will be left at the end of the fiscal year with a fiscal deficit higher than they forecast and an even weaker economy than exists now.

My assessment is that the fiscal deficit should be much larger this year and next than it is projected to be and that means the projected fiscal contraction is irresponsible.

The private sector’s debt position is set to worsen

The economic predictions, which underpin the fiscal statement and are contained in Budget Paper No.1, show that the Treasury is forecasting the following outcomes:

1. The fiscal deficit for 2017-18 of just 1 per cent of GDP reducing to 0.8 per cent of GDP in 2018-19, then into surplus -.1 per cent of GDP (2019-20), surplus of 0.5 per cent (2020-21) and a surplus of 0.8 per cent in 2021-22.

2. The current account deficit is projected to be 2.25 per cent of GDP in 2017-18, rising to 2.75 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 and 3.25 per cent of GDP in 2019-20.

The average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2016-17 has been -4 per cent of GDP. So the projections are considerably different to that long-term performance and for that reason they are suspect.

So what does that all mean in terms of the sectoral balances?

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

The sectoral balances equation is:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector to net save (S – I > 0).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to accumulate financial assets.

Expression (1) can also be written as:

(2) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting.

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2021-22, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in ‘Budget Paper No.1’.

The vertical black line demarcates the actual from the projected data.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) more or less projected to be constant over the forward estimates period, the private domestic balance overall (solid red line) is the mirror image of the projected government balance (blue line).

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit. This not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to rebalance its precarious debt position somewhat.

You can see the red line moves into surplus or close to it. The long-run average private domestic deficit is 2.4 per cent of GDP and was achieved largely when the household saving ratio was between 10 and 16 per cent and private investment in capital formation was strong.

The fiscal strategy outlined by the Government last night now implies as the graph shows that the private domestic sector will once again be accumulating debt as it progressively spends more than its income.

If you do not believe the very optimistic external deficit assumptions built into the fiscal strategy (join the crowd), then the dotted lines show an alternative scenario based on the long-term average current account deficit of 4 per cent.

Under this more realistic assumption, the private domestic sector experiences increasing deficits – heading towards the pre-GFC levels.

Either way, we are on the path back to the excessive private domestic debt levels that prevailed before the GFC.

If the projections are to be believed then the Government is expecting the private domestic sector to maintain the growth in the economy by increasing its indebtedness.

That would mean we are heading in the same direction as before the crisis – growth becomes reliant on private debt buildup.

The whole nation is transfixed on fears that the government debt in Australia is too high – courtesy of all the scaremongering that has been going on. But nary a word gets mentioned about the dangerous private debt levels. It is true that most of the debt is owed by higher income people in Australia, which makes an insolvency crisis of the likes of the sub-prime less likely here.

But the reality is that the debt levels and the growth in them (about the same as disposable income) means that consumer spending is likely to remain fairly subdued overall. It is unlikely we will see a return to the pre-crisis period when debt grew much faster than disposable income and the resulting spending maintained stronger economic growth.

Climate issues

Nothing. Which means zilch.

Which means head in the sand.

Which means much more to future generations than any of the fiscal aggregates and speed limits and all the rest of it.

Total abandonment from this government.

Unemployed in Australia forced by government to live below the poverty line – and it is getting worse

In the lead up to this week’s fiscal policy statement from the Treasurer, even conservative commentators and industry group leaders have been calling for the Government to end it malicious treatment of those unemployed living on the Newstart allowance (unemployment benefits).

There has been a growing chorus calling for the Government to significantly lift the Newstart allowance.

The Treasurer ignored the call and continued the Government’s appalling record in this area of socio-economic policy.

I have previously considered the state of poverty among the unemployed in these blog posts:

1. Why are we so mean to the unemployed? (September 23, 2009).

2. The plight of the unemployed – under growth and decay (November 16, 2010).

3. Our pathological meanness to the unemployed is just bad economics (February 15, 2012).

4. Fat cat bankster wants to make the unemployed even more desperate (August 23, 2012).

5. The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals (April 30, 2013).

6. Anti-Poverty Week – best solution is job creation (October 14, 2013).

7. Australia – where victims become criminals (December 12, 2016).

Things have deteriorated further since then.

For overseas readers here is some background. Unlike the unemployment compensation insurance schemes that operate in most countries, the Australian unemployment benefits system is paid by the federal government at set rates for an indefinite period (subject to Work Activity tests).

Employers and employees do not contribute to the scheme and everyone gets the same rate (adjusted for marital and parental status).

The current federal government is attempting to make matters worse for the unemployed. It is hard to see how they can succeed given how bad conditions already are.

The unemployment benefit system was originally designed to provide income support for those who fell into unemployment in an environment where long-term unemployment was rare (and defined as 12 weeks or more rather than 52 weeks or more as it is now) and the nation enjoyed true full employment.

Unemployment overall was always below 2 per cent and there was no underemployment.

At that time, spells of unemployment were short and most people could quickly find a new job if they were unlucky enough to become unemployed. Unfilled vacancies were usually above the level of unemployment which meant that firms were always looking for workers and provided training slots with job offers to ensure they could fill vacancies.

Unemployment benefits were thus designed to be a means of short-term income support in an economy where the national government took responsibility for ensuring there were always enough jobs available to match the preferences of the available labour force.

Fiscal policy settings were adjusted to maintain full employment and there was always a buffer stock of jobs available within various areas of the public sector to absorb workers unable to find work in the private sector.

The system turned in the 1970s as the blight of neo-liberalism started to take hold. On the one hand, the neo-liberals started to obsess about fiscal surpluses, which created rising mass unemployment for the first time since the Great Depression.

On the other hand, they began looking for victims to blame for the mess that their austerity policies were creating – that is, the high unemployment that they created by abandoning active fiscal policy and relying monetary policy to use unemployment as a policy tool to keep inflation low.

In 1994, the OECD consolidated the so-called ‘supply-side’ approach to labour market policy when it released its Jobs Study. The program they outlined accelerated the attacks on the unemployed and began the focus, in earnest, on ‘work tests’ and all the rest of the pernicious suite of administrative practices that have become commonplace.

At the time, it was obvious the economy was not producing enough jobs yet to disguise that a full-blown attack began on the unemployed and the narrative shifted to claims that their allowances were too high and were undermining incentives to work.

Quite simply, it was argued that our disadvantaged citizens preferred the pittance that the government provided them by way of unemployment benefits to working despite the fact that being unemployed exposed them to public humiliation, vilification from the media and civic leaders, and poverty.

Somehow, successive governments were able to convince us that these characters were lazy and living high on the hog and should be working like us. The argument relied on a sort of collective denial or ignorance of the reality – the data – the lack of jobs – whatever you want to call it.

When those arguments were raised, relevant Government Ministers would perjure themselves with creative stories such as “there are plenty of jobs it is just that the firms have stopped advertising them because they know the dole bludgers won’t take them anyway”.

Our national government has led the way in this inhumanity. It has deliberately chosen, not only to ensure their fiscal settings create worsening unemployment by suppressing aggregate spending, but then, if that wasn’t bad enough, to suppress the income support payments to worsen the poverty that unemployment brings.

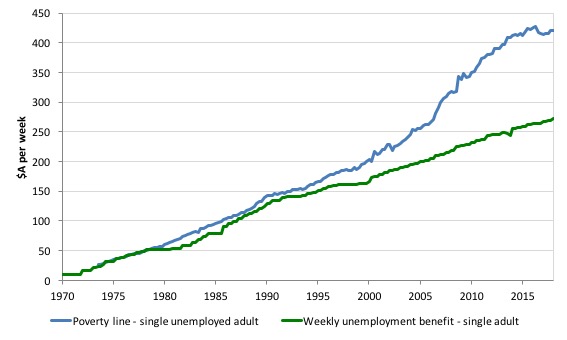

Here is an update to December 2017 (which is when the latest poverty line data is available to).

All the calculations that follow are taken from the following data sources:

The Newstart Allowance (unemployment benefit) is adjusted every March and September.

The following graph shows the evolution of the Single Unemployment Benefit and the Single Unemployed Poverty Line from the March-quarter 1970 until the December-quarter 2017.

The trends are clear.

In the September-quarter 2016, the single unemployment benefit was $A38.99 a day which is well below any reasonable estimate of the poverty line in Australia (for singles at $A60.02 per day).

For married couples the unemployment benefit as $A70.40 per day, while the corresponding poverty line is set at $A85.00 per day.

Whether one is single or in a couple, once accommodation is paid for, there is not very much left of the unemployment benefit income.

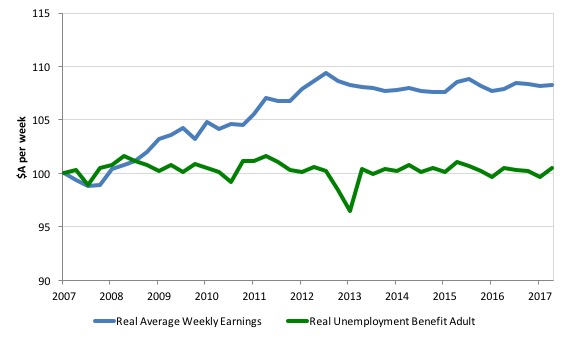

The next graph shows Average weekly earnings and the Adult unemployment benefit delated by the Consumer Price Index and indexed to 100 in the December-quarter 2007. This quarter was the peak of the last cycle. The real single and married unemployment benefits indexes have moved together since that time.

I should note that productivity has been rising well above the rate of real average weekly earnings since the early 1980s so there has been a further redistribution of national income away from workers generally over the last 30 years to profits.

But even with that dynamic unfolding, real average weekly earnings grew modestly up until the June-1uarter 2013 and since then real AWE has fallen slightly – real wages are being cut for Australian workers on average.

Since December 2007, real average weekly earnings have grown by just 8.3 per cent, which is pitiful.

However, real unemployment benefits have not improved at all.

So the Government has not only deprived the unemployed of the chance to gain employment by maintaining fiscal policy excessively tight, but is also denying them, by holding the unemployment benefit constant in real terms, the right to share in the benefits of national productivity gains.

Sure enough the unemployed haven’t done the work. But the Government’s fiscal policy stance has deliberately locked them out of employment and further forced them to fall behind other income groups in Australia.

I know that the unemployed receive some housing assistance in addition to the unemployment benefit which reduces, to some extent, the severity of the problem.

In the past, the Federal government (in liaison with the states) provided public housing to low income earners. While in short supply and of a fairly rudimentary quality, most low income earners could expect to be given access to a secure, affordable home.

But that housing provision changed when the neo-liberal ideology became dominant and the Government moved progressively to providing rent subsidies to private market suppliers rather than taking responsibility for providing housing itself.

There is a large literature which analyses the consequences of this shift for low income earners, which is tangential to this blog post.

The major conclusions of this literature:

1. Commonwealth Rental Assistance has failed to match the rise in housing costs so the real value of the subsidy has been progressively undermined.

2. This erosion in value has meant that single unemployed people find it almost impossible to rent in the private markets in the major capital cities such as Melbourne and Sydney which means that the spatial concentration of disadvantage rises and the unemployed are forced to live in areas where there is less job creation (notwithstanding the overall lack of job creation in Australia per se.

3. Commonwealth Rental Assistance relies on an adequate provision of affordable housing being made available by private providers. It is clear that supply has been lagging well behind demand for a number of reasons including the incentives given via the tax system to high income earners to invest in higher valued investment housing as tax dodges under negative gearing. This high income-earner welfare is a major source of inequity in the Australian system.

4. Many unemployed are forced to live in group (shared) housing and the maximum Commonwealth Rental Assistance entitlement is then dramatically reduced.

For further discussion, please read the blog Our pathological meanness to the unemployed is just bad economics – for more discussion.

The reality is this.

Even if the unemployed person is receiving the maximum rental assistance (around 75 per cent qualify at that rate such is the cost of housing in Australia), they still remain well below the poverty line.

Conclusion

The foresight of the Government and the care for the people it is elected by is severely exposed in this fiscal statement.

It has been framed to improve the election prospects of the Government and has limited economic coherence.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It certainly was a breath of Fresh air amongst all the political cant to see Get Up’s Youtube manifesto.

I mentioned it on Facebook and Steven Hail replied that people with MMT knowledge were behind it. Really good!

“Ridiculous fiscal rules”

Excellent explanation. Thank you.

Would it be much of a tin-foil-hat moment for me to suggest that the Libs know they’re going to lose the election, and are setting up the Budget to predictably tank for Labor?

I doubt they have that level of understanding Matt.

But Labor’s fiscal policy will do it anyway, and then they’ll get to say we told you so: “Labor can’t manage the economy.”

As Labor’s policies currently stand, it might be better for the progressive elements within the party to lose the election and then have a post mortem clean-out of all the Neolibs in the leadership.

The wild card will be GetUp.

I haven’t read all the blog yet, but wanted to thank Bill for the heads up about Get Up getting behind MMT and a JG. That’s great news! Get up have reach and respect- great allies to have.

This is so depressing.

Your unemployment benefits are poverty income. Tight fiscal policy keeps them out of employment. You then say to them: you are a leech.

Can never underestimate how evil the people at the top can be.

I think the problem is much much worse though. Many lucky people can stay with their parents (like me) and still be okay.

“Consider the following graph, which shows government payments and receipts as a percentage of GDP from 1970-71 out to 2021-22”

Hi Bill,

Can you please tell me the ABS data you are using for your govt payments and receipts?

cheers

Dear Dean (at 2018/05/18 at 11:22 am)

The full financial year dataset is published as an historical appendix to the “Budget Paper No. 1” (from 1970-71).

best wishes

bill