Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australian real wages growth flat – the ripoff of workers continues

Today (November 15, 2017), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the – Wage Price Index, Australia – for the September-quarter 2017. Private sector wages growth was marginally higher in the September-quarter at 1.86 per cent (annualised) after six consecutive quarters of record low growth. However, with the annual inflation rate running at 1.83 per cent, real wages barely moved. This follows two-quarters of real wage cuts. With real wages growth lagging badly behind productivity growth, the wage share in national income is now around record low levels. This represents a major rip-off for workers. The flat wages trend is also intensifying the pre-crisis dynamics, which saw private sector credit rather than real wages drive growth in consumption spending. Further, the forward estimates for fiscal outcomes provided by the Australian government are now not achievable, given the flat wages growth. There is no way the tax receipts will rise in line with the projections, which assumed much stronger wages and employment growth than will occur under current austerity-type fiscal settings.

Nominal wage and price inflation and real wage trends in Australia

The ABS Media Release (November 15, 2017) said:

The seasonally adjusted Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.5 per cent in the September quarter 2017 and 2.0 per cent over the year …

The WPI, seasonally adjusted, has recorded quarterly wages growth in the range of 0.4 to 0.6 per cent for the last 13 quarters (from the June quarter 2014).

Seasonally adjusted, private sector wages rose 1.9 per cent …

This result continues a sequence of quarters where wages growth has been just on or slightly below the annual inflation, meaning real wages have been static at best.

The wage series used in this blog is the quarterly ABS Wage Price Index published by the ABS. The Non-farm labour productivity per hour series is derived from the quarterly National Accounts.

Productivity data available via the RBA Table H2 Labour Costs and Productivity.

Please read my blog – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

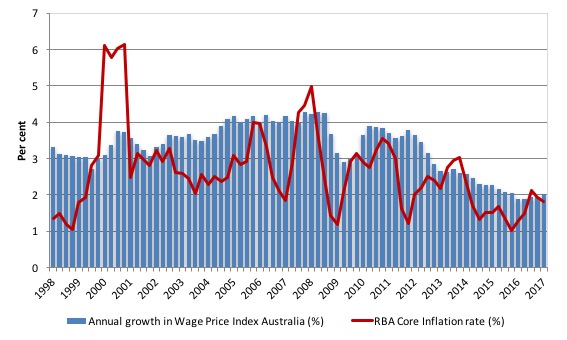

The first graph shows the overall annual growth in the Wage Price Index since the September-quarter 1998 (series was first published in the September-quarter 1997).

I also superimposed the annual inflation rate (red line). The bars above the red line indicate real wages growth and below the opposite.

In the September-quarter, the private sector WPI rose by 1.83 per cent on an annual basis compared to the RBA core inflation measure of 1.86 per cent, meaning that the real purchasing power of the vast majority of workers’ wages rose marginally after two quarters of cuts.

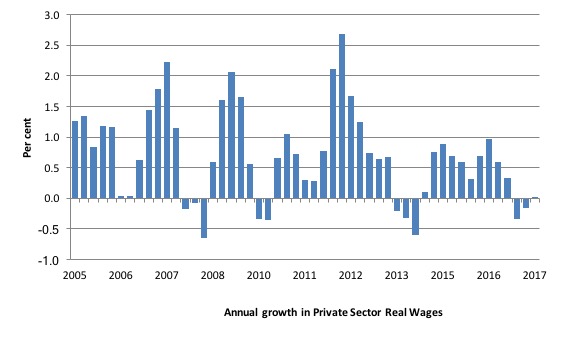

The following graph shows the annual growth in private sector real wages since the June-quarter 2005 to the September-quarter 2017.

After a few quarters of hard real wage cutting in 2013-14, the private sector returned to positive real wages growth but at very subdued rates.

In the March-quarter 2017, real wages growth was negative (-0.3 per cent) and in the June-quarter it was -0.2 per cent.

The two-decimal point results for the September-quarter show that private sector WPI rose by 1.86 per cent on an annual basis while the inflation rate was 1.86.

In other words, after rounding is taken into account, there was virtually zero real wages growth.

The rise in real wages in 2012 into 2013 was the result of the strong economic growth supported by the fiscal stimulus. The declining profile after that is associated with the end of the mining investment boom exacerbated by the obsessive fiscal restraint that was introduced (too early) and has led to the economy stalling.

The low wages growth raises several questions that are not unique to the Australian setting.

1. The low wages growth threatens to undermine household consumption expenditure, which is the largest component of aggregate spending. This fuels renewed demand for credit despite the fact that Australian households are already carrying record levels of debt (see Point 3).

2. The Australian government is mired in a trap of its own making – it still seeks to withdraw billions in public spending (a significant cut) because in its blinkered eyes the fiscal deficit is too large. Its fiscal aspirations for a surplus not only require this withdrawal but also a major rebound in tax revenue.

With wages growth so low – there is no income tax bracket creep going on (people paying higher tax because they move into higher brackets) and tax receipts are falling well below forecasts.

The ‘surplus obsession’ mindset is likely to see the government try to cut elsewhere to make up the shortfall – and the vicious cycle of fiscal austerity, low growth, low wages growth – and more mindless austerity will continue.

3. Australian households are carrying record levels of debt and their position is made more precarious by the low wages growth. Please read my blog – Australia’s household debt problem is not new – it is a neo-liberal product – for more discussion on this point.

The most recent retail sales data showed that household spending has fallen dramatically in recent months, indicating that perhaps the debt-fuelled growth phase is faltering.

Please read my blog – Retail sales dive in Australia – neoliberal contradictions now obvious – for more discussion on this point.

As households cut spending, growth will falter and growth in taxation receipts will fall – the Federal government is then just chasing its own tail at the expense of the unemployed who have to wear the costs of this folly.

Suppressing growth also leads to this declining wages growth profile, which further undermines the tax base of the Government.

Damaging circularity like this are characteristic of the neo-liberal era.

Workers not sharing in productivity growth

Not only has real wages growth ground to a standstill in Australia but it is clear that workers have not been sharing in the productivity growth generated in the Australian economy for several quarters.

Productivity growth provides the ‘non-inflationary’ space for real wages to grow and for material standards of living to rise.

But, one of the salient features of the neo-liberal era has been the on-going redistribution of national income to profits away from wages. This feature is present in many nations.

This has occurred because real wages growth has lagged behind productivity growth and the extra real income produced as been expropriated by capital in the form of profits.

The suppression of real wages growth has been a deliberate strategy of business firms, exploiting the entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment over the last two or three decades.

The aspirations of capital have been aided and abetted by a sequence of ‘pro-business’ governments who have introduced harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce the trade unions’ ability to achieve wage gains for their members. The casualisation of the labour market has also contributed to the suppression.

The so-called ‘free trade’ agreements, which are currently in the spotlight, have also contributed to this trend.

That redistribution of national income to profits continues in Australia. The wage share is now at around its lowest historical levels (at 51.9 per cent)

I consider the implications of that dynamic in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis. As you will see, I argue that without fundamental change in the way governments approach wage determination, the world economies will remain prone to crises.

In summary, the substantial redistribution of national income towards capital over the last 30 years has undermined the capacity of households to maintain consumption growth without recourse to debt.

One of the reasons that household debt levels are now at record levels is that real wages have lagged behind productivity growth and households have resorted to increased credit to maintain their consumption levels, a trend exacerbated by the financial deregulation and lax oversight of the financial sector.

Historically (for periods which data is available), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards. Higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth then spawned new activity and jobs, which absorbed the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

The neo-liberal period marked a shift in that relationship.

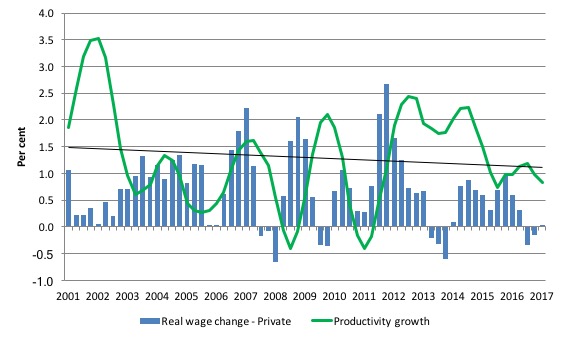

The next graph shows the annual hourly real wage change for the private sector (blue bars) and the annual hourly productivity growth (green line) since the June-quarter 2001, expressed as a 6-quarter moving-average to filter out the volatility in the series. The black line is the trend productivity growth over the same time period.

Productivity growth is currently close to trend and over the last 5 years has been mostly well above the growth in real wages.

Clearly, since the March-quarter 2011, the payoff to workers from the positive productivity growth has been less than proportional with real wages growth lagging productivity growth.

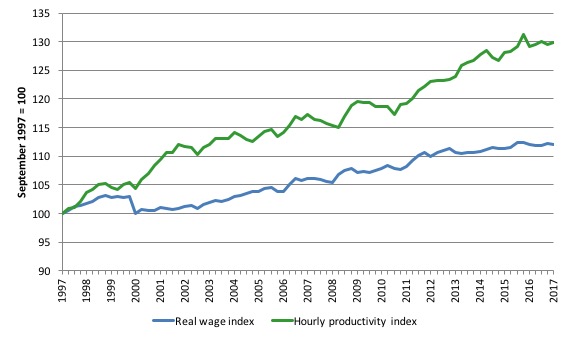

Taking a longer view, the following graph shows the total hourly rates of pay in the private sector in real terms (deflated with the CPI) (blue line) from the inception of the Wage Price Index (September-quarter 1997) and the real GDP per hour worked (from the national accounts) (green line) to the September-quarter 2017.

Over that time, the real hourly wage index has grown by 12.1 per cent, while the hourly productivity index has grown by 29.8 per cent.

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the productivity index would stand at around 180 and the real wage index at around 115. Data discontinuities however prevent a concise graph of this type being provided at this stage.

This gap represents a massive redistribution of national income to profits and away from wage-earners. For more analysis of why the gap represents a shift in national income shares and why it matters, please read the blog – Australia – stagnant wages growth continues.

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Mostly to profits.

One might then claim that investment will be stimulated.

At the onset of the GFC (December-quarter 2007), the Investment ratio (percentage of private investment in productive capital to GDP) was 23.8 per cent.

It peaked at 24.3 per cent in the September-quarter 2013. But in recent quarters as the gap between real wages growth and productivity growth widens, the Investment ratio has fallen and in the June-quarter 2017 (most recent data) it stood at 19.2 per cent (down from 19.6 per cent in the March-quarter 2017).

Some of the redistributed national income has gone into paying the massive and obscene executive salaries that we occasionally get wind of.

Some will be retained by firms and invested in financial markets fuelling the speculative bubbles around the world.

Real wages growth and employment

The recent labour force data has revealed that employment growth has been picking up in recent months after several years of very flat outcomes.

The standard mainstream argument that unemployment is a result of excessive real wages and moderating real wages should drive stronger employment growth.

The problem with this ‘theory’, when applied to the recent Australian experience, is that wages growth has been moderate for several years now while employment growth has been zig-zagging across the zero line over the same period – but generally very weak itself.

Very long (unbelievable) lags would have to be operating in the relationship for it to have any empirical credence.

The coincidence of both the predominantly flat wages growth and the poor employment growth for the last several quarters is supportive of the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position – that both are responding to the weak overall spending in the economy.

Firms will not employ new labour, no matter how cheap it becomes, if they cannot sell the extra goods and services that would be produced.

The claim that real wage cuts or growth retardation is necessary to stimulate employment is never borne out by the evidence.

As Keynes and many others have shown – wages have two aspects:

First, they add to unit costs, although by how much is moot, given that there is strong evidence that higher wages motivate higher productivity, which offsets the impact of the wage rises on unit costs.

Second, they add to income and consumption expenditure is directly related to the income that workers receive.

So it is not obvious that higher real wages undermine total spending in the economy. Employment growth is a direct function of spending and cutting real wages will only increase employment if you can argue (and show) that it increases spending and reduces the desire to save.

There is no evidence to suggest that would be the case.

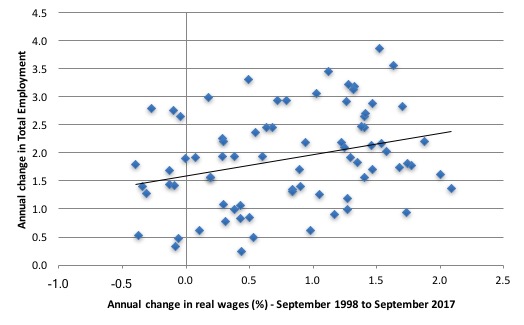

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages (horizontal axis) and the quarterly change in total employment (vertical axis). The period is from the September-quarter 1998 to the September-quarter 2017. The solid line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: When real wages grow faster so does employment although from a two-dimensional graph causality is impossible to determine.

However, there is strong evidence that both employment growth and real wages growth respond positively to total spending growth and increasing economic activity. That evidence supports the positive relationship between real wages growth and employment growth.

Conclusion

Australia continues to endure near record-low wages growth. In the September-quarter private sector real wages growth was around zero, which followed two consecutive quarters of negative real wages growth.

The slow wages growth is a cause and reflection of the slow growth in overall economic activity and employment as well as major shifts in the type of employment that is on offer.

The persistent unemployment, the rise in underemployment and the depressed participation rates (rise in hidden underemployment) mean that broad labour underutilisation is over 15 per cent (conservative estimate) in Australia.

That is a massive waste of labour and foregone income. It cannot be explained through worker preference. It is all about a shortage of job creation stifled by excessively restrictive fiscal policy settings.

In turn, workers are adopting a much more cautious approach to spending and firms are demonstrating that they will not lift the investment rate while sales are flagging.

Taken together, these are the reasons that real wages are flat.

The resulting subdued economic activity will also undermine the Government’s fiscal strategy, which can be summarised as squeezing net public spending out of the economy in the hope that they will achieve a fiscal surplus by 2020-21.

Economic growth and wages growth, in particular, will not be strong enough to match their assumptions and that means the growth in tax receipts will be less than assumed.

It would be better for the Government to stimulate the economy more now with larger fiscal deficits and then see the fiscal balance drop on the back of income growth.

Higher (and more reasonable) wages growth would both benefit from and provide support to such a fiscal strategy.

At the moment, we are in a race-to-the-bottom, which is nowhere any reasonable policy strategy should aim for.

Celebrating the 61.6 per cent YES vote in Australia’s same-sex marriage survey

This is worth noting for historical purposes.

Australia just completed a national postal vote on the question: Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?

The ABS released the results today (November 15, 2017) – Australia supports changing the law to allow same-sex couples to marry.

61.6 per cent voted Yes nationally with 79.5 per cent voting (it was voluntary – normal elections are compulsory).

About time.

74.8 per cent in Newcastle electorate (my main home) voted Yes.

83.7 per cent in the Melbourne electorate (my other home) voted Yes – this was the largest support nationally.

Good to be living near sensible people.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Is it that an “internal devaluation” is being pursued? Business lobbyists accuse our wage level of being internationally “uncompetitive”. If so they are aiming for a race to the bottom.

How long can the remarkable divergence of outcomes for workers/consumers and business conditions continue I wonder?

Australian workers income growth posts yet another dismal result……while the business conditions survey posts yet another roaring positive with overall conditions at the highest level on record. Perhaps one is weighted incorrectly or something.

Clearly, retail business overall is feeling the pinch but despite it being a large part of the domestic economy, it’s boom times for business generally apparently.

The spending to fuel strong business performance and an at least somewhat improved labour market must be coming from somewhere, it obviously isn’t from wage and salary growth.

Bill,

What specific data series from the spreadsheets are used for the annual growth in private sector real wages graph?