Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian labour force – negative employment growth and rising unemployment

This analysis is coming from Brussels and the data doesn’t look any better here than it does back in Australia. The situation being revealed is very poor. The latest labour force data released today by the Australian Bureau of Statistics – Labour Force data – for February 2017 shows total employment fell by 6,400 and repeats the behaviour of the last few years where it has been zig-zagging around the zero growth line on a more or less monthly basis. Australia’s status as a part-time employment nation continues, despite a modest rise in full-time employment this month. Over the last 12 months, Australia has lost 23.2 thousand full-time jobs (in net terms) and gained 127.8 thousand part-time jobs. Overall, employment has grown by only 104.6 thousand jobs (net) – a very low annual figure. This status as the nation of part-time employment growth carries many attendant negative consequences – poor income growth, precarious work, lack of skill development etc. The failure of employment to keep pace with the labour force growth saw unemployment rise sharply in February 2017 by 26 thousand and the unemployment rate to rise by 0.2 points to 5.9 per cent. Underemployment also rose sharply by 0.3 points to 8.7 per cent and taken together (unemployment and underemployment) there were 14.6 per cent of the labour force counted as broadly underutilised (1,862.7 thousand). The teenage labour market remains in a poor state and deteriorated further in February. It requires urgent policy intervention. Overall, the Australian labour market is weak and showing no signs of improvement. The poor outlook signals the need for a policy shift biased to expansion. It is clear that the current restrictive fiscal policy position adopted by the Federal government is not sufficient to redress the inadequate non-government spending growth.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for February 2017 are:

- Employment decreased by 6,400 (0.1 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 27,100 and part-time employment decreasing by 33,500.

- Unemployment increased by 26,000 to 748,100.

- The official unemployment rate rose by 0.2 points to 5.9 per cent.

- The participation rate was steady at 64.6 per cent. Its behaviour has been quite erratic over the last 6 months. It remains well below its December 2010 peak (recent) of 65.8 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 20.5 million hours (1.22 per cent).

- The latest quarterly broad labour underutilisation data was published this month (for the February-quarter 2017). Underemployment rose from 8.4 per cent of the labour force in the December-quarter 2016 to 8.7 per cent in the February-quarter 2017. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) rose from 14.1 per cent to 14.6 per cent (as a result of both elements rising). There were 1,114.6 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1,862.7 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

Employment growth – turns negative again

Employment decreased by 6,400 (0.1 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 27,100 and part-time employment decreasing by 33,500.

While full-time employment rose a little this month, it remains the fact that Australia has become a part-time employment nation.

In seasonally-adjusted terms, 127.8 per cent of the net jobs created in Australia in the last 12 months have been part-time.

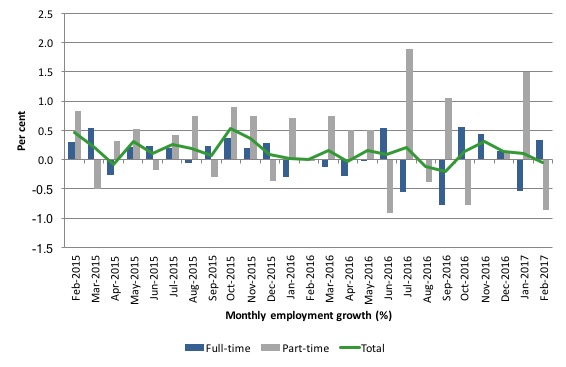

The zig-zag pattern that we have observed over the last 36 months or so – where the employment estimates have been switching back and forth regularly between negative employment growth and positive growth with the occasional spikes – continues.

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to February 2017 using seasonally adjusted data.

It gives you a good impression of just how flat employment growth has been over the last 2 years. You can also see the dominance of part-time employment growth over the same period, especially in the last year or so.

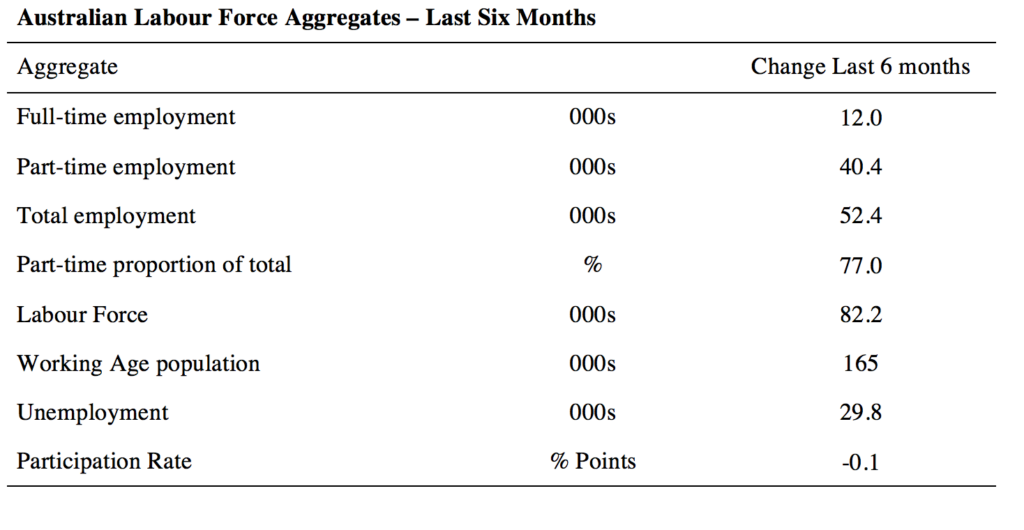

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. The monthly data is highly variable so this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends. WAP is working age population (above 15 year olds).

Full-time employment has risen risen by 12 thousand jobs (net) over the last 6 months (the shift from a negative to positive change all occurring this month), while part-time work has risen by 40.4 thousand jobs.

The conclusion – overall there have only been 52.4 thousand jobs (net) added in Australia over the last six months while the labour force has increased by 82.2 thousand. Employment growth has thus failed to keep pace with underlying population growth (even with the participation rate falling by 0.1 points). The result has been that unemployment has risen by 29.8 thousand.

Overall – a very weak labour market.

And a failing policy structure.

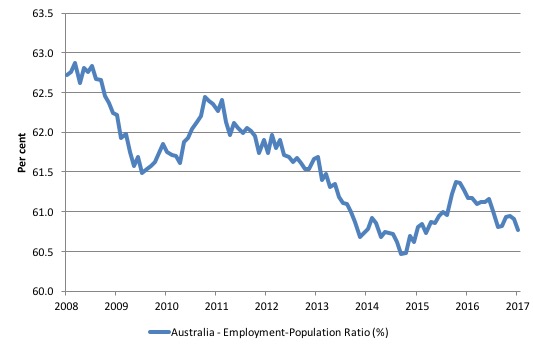

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since February 2008 (the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

It dived with the onset of the GFC, recovered under the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus packages but then went backwards again as the last Federal government imposed fiscal austerity in a hare-brained attempt at achieving a fiscal surplus.

The ratio began rising in December 2014 which suggested to some that the labour market had bottomed out and would improve slowly as long as there are no major policy contractions or cuts in private capital formation.

However, the peak in December is now gone and the ratio is once again in retreat.

The on-going fiscal deficit is still supporting some growth in the economy as the spending associated with the mining boom disappears. But the deficit is clearly too small given the behaviour of the real aggregates.

The series fell by 0.1 points in February 2017 to 60.8 per cent and remains a staggering 2.1 percentage points below the April 2008 peak of 62.9 per cent.

There is no good news here.

Teenage labour market – deteriorates further in February 2017

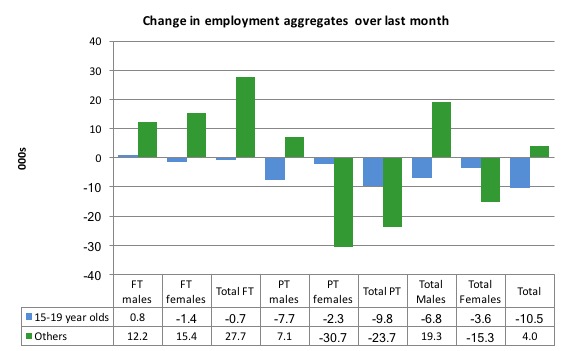

The teenage labour market saw full-time employment fall by 0.7 thousand jobs and part-time employment fall by 9.8 thousand (net) jobs in February 2017.

Total employment thus fell by 10.5 thousand (net), which continues a long-term deterioration in this labour market segment.

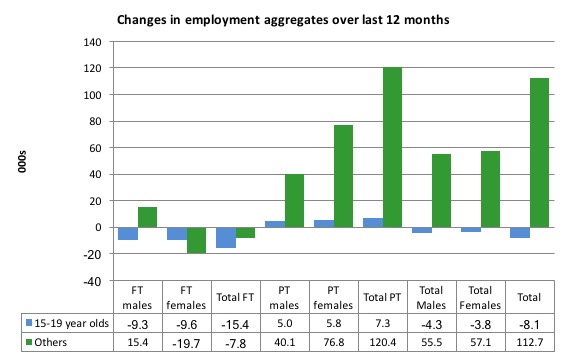

The following graph shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest)

Over the last 12 months, teenagers have lost 8.1 thousand (net) jobs overall while the rest of the labour force have gained 112.7 thousand net jobs. Remember that the overall result represents a fairly poor annual growth in employment.

Full-time employment for teenagers over the last 12 months has fallen by 15.4 thousand and they have barely participated in the part-time employment growth (where they are traditionally strongly represented) – up 7.3 thousand.

The teenage segment of the labour market is being particularly dragged down by the sluggish employment growth, which is hardly surprising given that the least experienced and/or most disadvantaged (those with disabilities etc) are rationed to the back of the queue by the employers.

The following graph shows the change in aggregates over the last 12 months. It is as if the teenagers have not had a stake in the labour market either way (blue bars barely visible).

In terms of the current cycle, which began after the last low-point unemployment rate month (February 2008), the following results are relevant:

1. Since February 2008, there have been only 1,351.3 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a staggering 107.8 thousand over the same period.

2. Since February 2008, teenagers have lost 126.1 thousand full-time jobs (net).

3. Even in the traditionally, concentrated teenage segment – part-time employment, teenagers have gained only 18.3 thousand jobs (net) even though 833.5 thousand part-time jobs have been added overall.

4. Overall, the total employment increase is modest. Further, around 61 per cent of the total (net) jobs added since February 2008 have been part-time, which raises questions about the quality of work that is being generated overall.

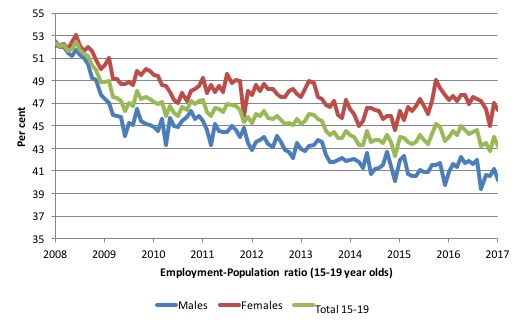

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since February 2008.

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The facts are that the absolute loss of jobs reported above is depicting a disastrous situation for our teenagers. Males, in particular, have lost out severely as a result of the economy being deliberately stifled by austerity policy positions.

In the latter months of 2015, with the part-time employment situation improving, there was some reversal in the downward trends in these ratios.

However, that short improvement has now disappeared and the ratios are once again trending downwards.

The male ratio has fallen by 12.3 percentage points since February 2008, the female ratio has fallen by 5.7 percentage points and the overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 9.1 percentage points. That is a substantial decline in the employment market for Australian teenagers.

The other staggering statistic relating to the teenage labour market is the decline in the participation rate since the beginning of 2008 when it peaked in January at 61.4 per cent. In February 2017, the participation rate was just 53.3 per cent.

That is an additional 121 thousand teenagers who have dropped out of the labour force as a result of the weak conditions since the crisis.

If we added them back into the labour force the teenage unemployment rate would be 29.6 per cent rather than the official estimate for February 2017 of 18.9 per cent.

Some may have decided to return to full-time education and abandoned their plans to work. But the data suggests the official unemployment rate is significantly understating the actual situation that teenagers face in the Australian labour market.

Overall, the performance of the teenage labour market remains extremely poor. It doesn’t rate much priority in the policy debate, which is surprising given that this is our future workforce in an ageing population. Future productivity growth will determine whether the ageing population enjoys a higher standard of living than now or goes backwards.

I continue to recommend that the Australian government immediately announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing all the unemployed 15-19 year olds, who are not in full-time education or a credible apprenticeship program.

Unemployment increased by 26,000 to 748,100

The official unemployment rate increased 0.2 points to 5.9 per cent in February 2017 because employment growth was negative and the labour force grew modestly.

Overall, the labour market still has significant excess capacity available in most areas and what growth there is is not making any major inroads into the idle pools of labour.

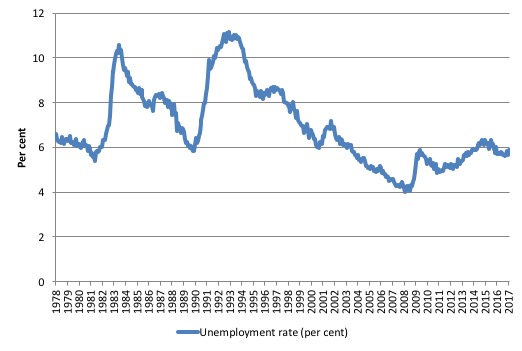

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from February 1978 to February 2017. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

After falling steadily as the fiscal stimulus pushed growth along, the unemployment rate slowly trended up for some months.

It is now above the peak that was reached just before the introduction of the fiscal stimulus. In other words, the gains that emerged in the recovery as a result of the fiscal stimulus in 2009-10 have now been lost.

Given the weak (negative) employment growth, the unemployment rate would be much higher if the labour force was growing as previous trend rates (see analysis below).

Broad labour underutilisation – rises sharply to 14.6 per cent

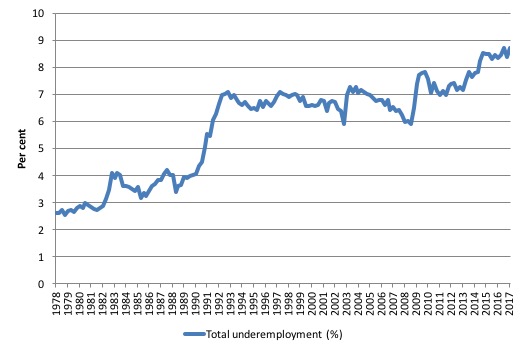

The ABS publishes monthly and quarterly labour underutilisation data. The quarterly data was updated this month (for the February-quarter 2017).

1. Underemployment rose from 8.4 per cent of the labour force in the December-quarter 2016 to 8.7 per cent in the February-quarter 2017.

2. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) rose from 14.1 per cent to 14.6 per cent (as a result of both elements rising).

3. There were 1,114.6 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1,862.7 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

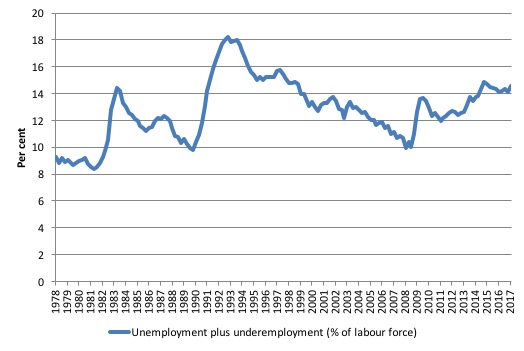

The following graph plots the history of quarterly (seasonally-adjusted) underemployment in Australia since February 1978 to the February-quarter 2017.

The next graph shows the evolution of the broad underutilisation rate over the same period. You can see the three cyclical peaks corresponding to the 1982, 1991 recessions and the more recent downturn.

Unemployment was a higher proportion of the two earlier peaks but underemployment now dominates the current cycle (just).

The other difference between now and the two earlier cycles is that the recovery triggered by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 did not persist and as soon as the ‘fiscal surplus’ fetish kicked in in 2012, things went backwards very quickly.

The two earlier peaks were sharp but steadily declined. The last peak fell away on the back of the stimulus but turned again when the stimulus was withdrawn.

If hidden unemployment (given the depressed participation rate) is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate well above 16 per cent at present. Please read my blog – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

The next update will be for the May-quarter 2017 and will be published published in the June 2017 Labour Force release. In between those releases, the monthly estimates are available to guide our thinking.

Aggregate participation rate – steady at 64.6 per cent and remains at depressed levels

The participation rate was steady at 64.6 per cent.

The participation rate remains substantially down on the most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.8 per cent when the labour market was still recovering courtesy of the fiscal stimulus.

There is considerable monthly fluctuation in the participation rate but the current rate of 64.6 per cent is a long way below its most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.8 per cent.

What would the unemployment rate be if the participation rate was at the last November 2010 peak level value?

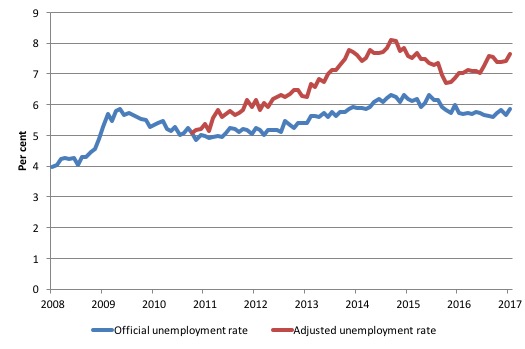

The following graph tells us what would have happened if the participation rate had been constant over the period November 2010 to February 2017. The blue line is the official unemployment rate since its most recent low-point of 4 per cent in February 2008.

The red line starts at November 2010 (the peak participation month). It is computed by adding the workers that left the labour force as employment growth faltered (and the participation rate fell) back into the labour force and assuming they would have been unemployed. At present, this cohort is likely to comprise a component of the hidden unemployed (or discouraged workers).

In recent months the gap between the lines has diverged which signals a deteriorating situation.

Total official unemployment in February 2017 was estimated to be 748.1 thousand. However, if participation had not have fallen relative to November 2010, there would be 992.5 thousand workers unemployed given growth in population and employment since November 2010.

The unemployment rate would now be 7.6 per cent if the participation had not fallen below its November 2010 peak of 65.8 per cent. The official unemployment in February 2017 was 5.9 per cent.

The difference between the two numbers mostly reflects, the change in hidden unemployment (discouraged workers) since November 2010. These workers would take a job immediately if offered one but have given up looking because there are not enough jobs and as a consequence the ABS classifies them as being Not in the Labour Force.

There has been some change in the age composition of the labour force (older workers with low participation rates becoming a higher proportion) but this only accounts for less than 1/3 of the shift. The rest is undoubtedly accounted for by the rise in hidden unemployment.

Note, the gap between the blue and red lines doesn’t sum to total hidden unemployment unless November 2010 was a full employment peak, which it clearly was not. The interpretation of the gap is that it shows the extra hidden unemployed since that time.

This gap shrinks as participation rises relative to the November 2010 peak.

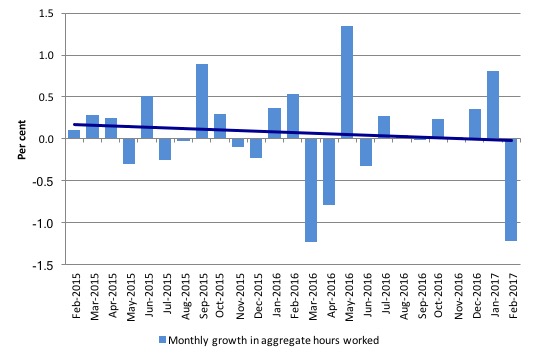

Hours worked – fell sharply by 1.22 per cent in February 2017

Seasonally-adjusted aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 20.5 million hours (1.22 per cent) in February 2017 despite the modest increase in full-time work.

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months. The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts a distinct negative trend.

You can see the pattern of the change in working hours is also portrayed in the employment graph – zig-zagging across the zero growth line.

Conclusion

I repeat my standard monthly warning – we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

Today’s figures show that the Australian labour market remains in a weak state. Total employment fell by 6,400 and repeats the behaviour of the last few years where it has been zig-zagging around the zero growth line on a more or less monthly basis.

Over the last 12 months, Australia has lost 23.2 thousand full-time jobs (in net terms) and gained 127.8 thousand part-time jobs.

Overall, employment has grown by only 104.6 thousand jobs (net) – a very low annual figure.

This status as the nation of part-time employment growth carries many attendant negative consequences – poor income growth, precarious work, lack of skill development etc.

The failure of employment to keep pace with the labour force growth saw unemployment rise sharply in February 2017 by 26 thousand and the unemployment rate to rise by 0.2 points to 5.9 per cent.

Underemployment also rose sharply by 0.3 points to 8.7 per cent and taken together (unemployment and underemployment) there were 14.6 per cent of the labour force counted as broadly underutilised (1,862.7 thousand).

The teenage labour market remains in a poor state and deteriorated further in February. It requires urgent policy intervention.

Overall, the Australian labour market is weak and showing no signs of improvement. The poor outlook signals the need for a policy shift biased to expansion.

It is clear that the current restrictive fiscal policy position adopted by the Federal government is not sufficient to redress the inadequate non-government spending growth.

Australia needs a rather sizeable fiscal stimulus.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

An increase in part-time employment plus a cut to wages thanks to the ‘fair’ work commission equals disaster at many levels

The aim; to ensure everyone is employed (who desires it) raises important issues for any economy operating in globalized trade, especially in terms of its competitive implications.

MMT seems to regard the stresses of international trade (strongly implying foreign superiority is often gained by unfairness) are sufficient to warrant a form of nationalism; the imposition of import tariffs etc.

This would provide a justifiable re-assertion of home production (mass manufacturing being a prime example), so that full employment programs can be established as an option for government policy; effectively a basis for a more equal and humanitarian society.

It might soon become apparent however, that this form of economic solution has the capacity to create its own disruption; causing home product costs to become internationally uncompetitive (raising the home-produced cost of goods in what is otherwise an international industry).

The outcome of this situation has the makings of its own unrest; because living standards are likely to be adversely affected during any home resistance to international evolution in either cost efficiency or new products.

In either outcome, MMT supporters may need to adjust to employment upheavals that contradict political and ideological aims; the resolution of social/industrial conflicts having become of prime political and moral importance – unlike when economic priorities held a more detached moral influence, and social (unemployment) issues tended to take a secondary role, except in grotesque periods of industrial-age history.

What appears to be inadequately recorded by MMT supporters is the overriding role of international competition in human affairs and its potential impact on living standards. Even if employment was rebuilt, productivity (which again we hear about inadequately) continues to play a decisive role in economic success, not least in the latest, advanced stage of industrial revolution that humanity has now entered.

And the encroaching influence of robotic development has not even been mentioned.

We live in an increasingly networked society (internet), so it is fair to ask whether society is inevitably becoming totalitarian anyway; or might we in the West describe it as a more open society.

China, which has its own broad internet services, could perhaps be described as having societal control. In the West our internet is dominated by the likes of Google, Facebook, Amazon.

These enterprises are nevertheless, able to learn a great deal about ourselves by virtue of our use of the internet.

We have long derided the encroachment of Communism into peoples lives. Is Western society also becoming totalitarian.

In Reply to Gogs;

I have only been reading about MMT for a short time but have not yet seen anything about the imposition of import tarriffs. I’m also confused about the ‘etc.’ you placed at the end of that sentence. Hopefully you can supply some link which can help me understand your criticism.

Dear Guy,

The imposition of import tariffs stems from evidence that the price of goods/commodities have been manipulated by way of subsidy, or similar process.

Bill has tackled the problem, emphasizing, among other things, the difference between “Fair” trade and “Free” trade. You can explore this matter more fully by referring to the blogs covering the issues: bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=34677 https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=34864, https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=34743,

Trade manipulation is not confined to a narrow range of actions, which is why I referred to the possibility of etc in my submission.

My regards