Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australia races to the low-pay bottom while employers’ lies are exposed

Over the last 12 months, it has been increasingly obvious that the Australia has become a part-time employment nation. While the trend towards increasing part-time employment as a proportion of the total has been with us since the 1970s, the nature of that trend has been changing in recent years and belies the claims by the mainstream that it is a reflection of increased choice by workers for better life-work balance and the rising proportion of women in the workforce combining family responsibilities with income earning opportunities. The reality is different. Overall, there is a lack of working hours being generated in Australia (as elsewhere) because macroeconomic policy is restrictive (fiscal deficit to low as a proportion of GDP). That rationing of job creation is giving way to more part-time work, higher levels of underemployment (part-time workers who desire more hours but cannot find them), higher proportions of casual work, and a bias towards jobs that provide low (below average) pay. And the pressure is on to cut pay and conditions even further as employers make spurious claims about the damage penalty rates (overtime rates at weekends) cause the economy. The problem for them is that a recent (leaked) report by a Citi Research (part of Citigroup), hardly a friend of the unions and workers, has exposed the truth – cuitting penalty rates will just boost profits and will not lead to increased employment.

Background

Coinciding with the latest ABS Labour Force data release, the agency said:

In October 2016, trend employment decreased by 1,000 persons to 11,946,600 persons, the first decrease in the trend series since November 2013. This slight fall in trend employment reflected an increase in part-time employment of 8,400 persons being more than offset by a decrease in full-time employment of 9,500 persons.

Since December 2015 we have seen a continued decline in trend full-time employment and an increase in part-time employment, with a corresponding increase in the share of hours worked by part-time workers. This shift to part-time employment has been more pronounced for males compared to females.

Over the past year, part-time employment has increased from around 31 per cent of employment to 32 per cent. That’s a relatively large shift, if you consider that it was around 29 per cent 10 years ago.

Since December 2015, there are now around 132,700 more persons working part-time, compared with a 69,900 decrease in those working full-time.

In seasonally-adjusted terms, 134 per cent of the net jobs created in Australia in the last 12 months have been part-time.

Over the last 6 months this trend intensified, with full-time employment going backwards and part-time employment accounting for 183 per cent of the net job creation.

It is also apparent that there has been an increasing trend to low-paid employment creation, which we consider later.

The penalty rates scam by employers exposed

A recent UK Guardian article (November 30, 2016) – Penalty rate cuts would boost retailer profits rather than jobs, study suggests – reported on a report produced by Citi Research (a division of Citigroup) which analysed the impacts of a cut in penalty rates in Australia.

The report was confidential and commissioned by “institutional investors in retail shares” but has become public in the best tradition that these sneaky documents that expose the lies of the elites seem to have a habit of reaching the public eye.

As background the following blogs might be of use:

1. No case made to cut penalty rates.

2. Penalty wage rates are still justified for non-standard hours work.

I have done a lot of work in the past on this topic and written several ‘cases’ for unions who have had to defend the retention of penalty rates in the Australian wage setting tribunals.

The employers’ groups have long seen penalty rates as a sort of beach head that they attack relentlessly. They seem to think if they can get rid of them, they are that much closer to cutting into holiday conditions, safety rules, and base pay rates. Their relentless attack on penalty rates has been nothing short of disgusting in its self-interest.

That is especially as it is typically the lowest paid workers in cleaning, cafes, accommodation etc that rely on the weekend rates to push themselves over the poverty line. Hacking into their wages – given how low their base rates for standard hours are – guarantees to push them back into poverty – working poverty.

While the pressure from the employers has been relentless in this regard they have so far they have been largely unsuccessful.

This is because their arguments always deny the obvious (the specialness of public holidays) and rely on the flawed reasoning that mainstream microeconomic textbooks inflict on students in our universities, which conclude (erroneously) that cutting wages increases employment and getting rid of penalty rates will somehow see lower prices and more food outlets (as if there aren’t already enough!).

In the blog – Penalty wage rates are still justified for non-standard hours work – I go through the reasons why the wage setting tribunals have to date rejected the stupid arguments presented to them by the employer groups.

The current conservative Australian government is very keen to get rid of penalty rates given it receives a major share of the corporate funding dollar and wants to be helping its rich mates get more of the real income pie rather than less.

The employer groups always claim that cutting penalty rates would boost employment and increase worker incomes as a result. It is a lie and has always been a lie.

Even the Productivity Commission, a neo-liberal, pro-market agency in Australia that examines big microeconomic issues, issued a report in August 2015 – Workplace Relations Framework – which couldn’t really find anything significantly wrong with our industrial relations system, despite the employer groups and the sycophantic economists they wheel out to support them, claiming that Australia was an impoverished, low productivity nation in danger of being left behind by the rest of the world as a result of out overly-generous wages and job protections.

The Productivity Commission, which grew out of the old Tariff Board (then Industries Assistance Commission) and so administered the trade protection policy of the Federal government in the C20th and has morphed into its current guise, which is to give advice to government on how to deregulate, privatise, outsource and other trash the conditions of workers, concluded, for example, in relation to unfair dismissal rules (job protection legislation) that our practices were “unlikely to have significant negative impacts on medium to large businesses, especially considering that their purpose is not to minimise costs to employers, but to balance the interests of both employees and employers”.

The Report had to admit that increases in our minimum wage levels (“high in Australia compared with most other countries”) do not have the disastrous effects that the employers keep predicting.

The Report also found no evidence that penalty rates should be scrapped. After making that case, almost out of thin air, the Commission claimed that double-time Sunday rates should be lowered to time-and-a-half Saturday rates. No reason was given other than the employers had long been arguing this – as the first chink in the system to create – on their way to scrapping rates altogether, which is their stated aim.

Now we have more information. It doesn’t help the employers’ case at all. In fact, it confirms what those who have been defending the existing penalty rate system (including yours truly) have been arguind all along.

The Citi Research report concluded that:

1. “A decrease in penalty rates would boost major retailers’ profits or result in tiny reductions in consumer prices without changing employment levels”.

2. “cutting Sunday penalty rates from double-time to time-and-a-half would increase earnings per share by up to 8%” for the large retailers.

3. “Citi does not anticipate retailers would hire more workers or increase shifts.”

4. “while Australia had higher wage rates, ‘productivity is also higher than offshore peers’. For example, Australian supermarkets have 10%-30% more sales per employee than their UK peers.”

Peak employer organisations, such as the Australian Industry Group have long argued otherwise. They lie.

Casual work is increasing

Which brings me to casual work.

In my recent October 2016 Labour Force analysis – Australian labour market – staggering along and in trend deterioration, I wrote:

The combination of very weak pay outcomes and an increasing bias towards part-time and casualised work has major ramifications for the nation, where the household sector is now bogged down with record levels of indebtedness. A perfect storm is brewing.

This was challenged by a commentator who cited a so-called Fact Check on The Conversation – FactCheck: has the level of casual employment in Australia stayed steady for the past 18 years? – published on March 23, 2016.

The FactCheck specifically analysed the veracity of claims made by the Australian Industry Group (AiG) as part of their on-going attack on penalty rates that “the level of casual employment has not increased in Australia for the past 18 years”.

The Conversation analysis found that claim to be true. Casual work has remained at around 20.1 per cent of total employment.

The data they draw on comes from the Australian Bureau of Statistics where the relevant publication is – 6105.0 Australian Labour Market Statistics – which was last published on July 8, 2014. It is an infrequent publication.

The relevant dataset from this publication is Employment Type.

As background, you might want to consult the briefing from the Australian Parliamentary Library (January 20, 2015 ) – Casual employment in Australia: a quick guide.

That guide helps understand that it is difficult to compute anything about casual employment because there “is no formal definition”.

The Australian Fair Work Ombudsman defines a casual employee as one who:

– has no guaranteed hours of work

– usually works irregular hours

– doesn’t get paid sick or annual leave

– can end employment without notice, unless notice is required by a registered agreement, award or employment contract.

They can be full-time or part-time.

To get some idea of the trends, the ABS collects data of employment type and distinguishes four categories which make up total employment:

- Employees with paid leave entitlements

- Employees without paid leave entitlements

- Owner managers of incorporated enterprises

- Owner managers of unincorporated enterprises

Within that classification, the proxy that people use to assess trends in casual work is the category – Employees without paid leave entitlements.

It is unsatisfactory but the best that we have data for.

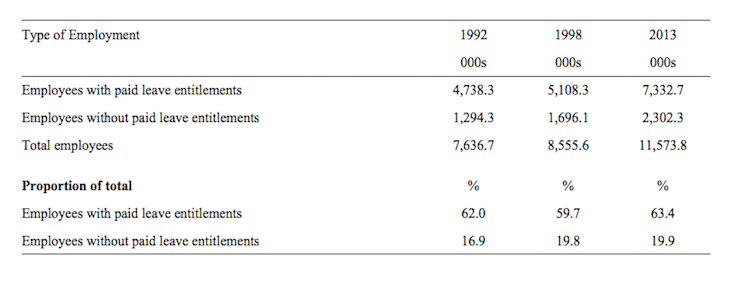

The following table summarises the results (noting the most recent data goes to 2013 only). It shows that the proportion of Employees without paid leave entitlements has in fact risen since the last recession.

From the Table 1, we see that between 1998 and 2013, the ratio of Employees without paid leave entitlements to total has risen marginally:

- 1998 1,696.1 thousand (total 8,555.6 thousand) proportion = 19.8 per cent.

- 2013 2,302.3 thousand (total 11,573.8 thousand) proportion = 19.9 per cent.

That was the point the commentator on my blog made. But the commentator didn’t mention that the data that was being quoted came from the Conversation Fact Check cited above, which was responding to a claim by an industry employer body (AiG) who have a vested interest in making out that there has not been an increase in casual employment as a proportion of the total.

That group consistently tries to use the wage setting tribunals in Australia to reduce working conditions and suppress wage rises.

So the choice of the sample (1998 to 2013) is very convenient and deliberately made to suppress the longer-term reality.

As the Table shows, the actual ABS data set runs from 1992 to 2013 and once we use this full period (which is the actual cycle since the 1991 recession) we get a very different story and one that is consistent with my claim that casual employment has risen in the cycle as a proportion of total employment.

Employees without paid leave entitlements:

- 1992, employees without paid leave entitlements (1,294.3 thousand) comprised 16.9 per cent of total employment.

- 2013 (the latest data available), this proportion had risen to 19.9 per cent (2302.3 thousand).

There is another Australian Bureau of Statistics data source that sheds some light on ‘casual employment’ (from the monthly Labour Force survey).

The latest data for casual arrangements is for May 2014, when the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 21.6 per cent of the 9,898.9 employees at that time were causal.

Total employment in May 2014 was 11,503 thousand so the incidence of casualisation will be even higher.

Bias towards Low Pay

I have previously analysed the bias towards low-pay jobs in the US. Please read my blog – Bias toward low-wage job creation in the US continues – for more discussion on this point.

I last analysed this issue for Australia in this blog – Australia’s race to the bottom to part-time jobs with low-pay.

This section updates that analysis to the August-quarter.

For Australia I have examined three periods:

1. The period since the peak (February 2008) to August 2016.

2. The last 12 months.

3. The last 6 months.

The questions of interest:

1. Has the trend to low-paid and/or below-average pay jobs accelerated over those three time horizons?

2. Is the dominance of part-time work over the last 12 months a sign of more lower-paying jobs relative to higher paying jobs?

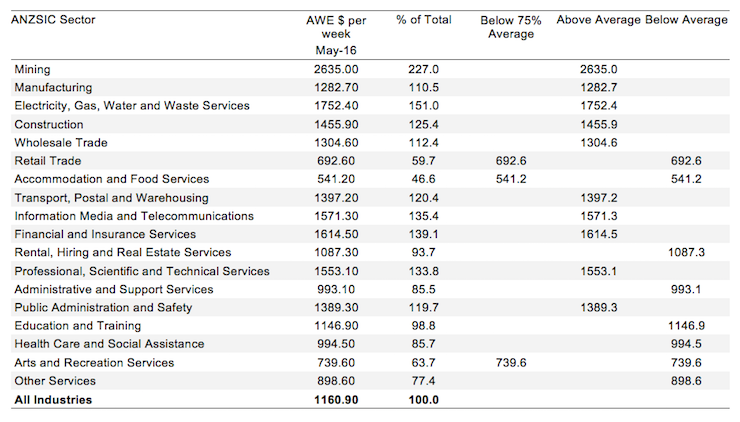

The first table looks at the industry distribution of total earnings as at August 2016 (the latest earnings by industry data available) using the top level ANZSIC (Australian and New Zealand Standard Industry Classification).

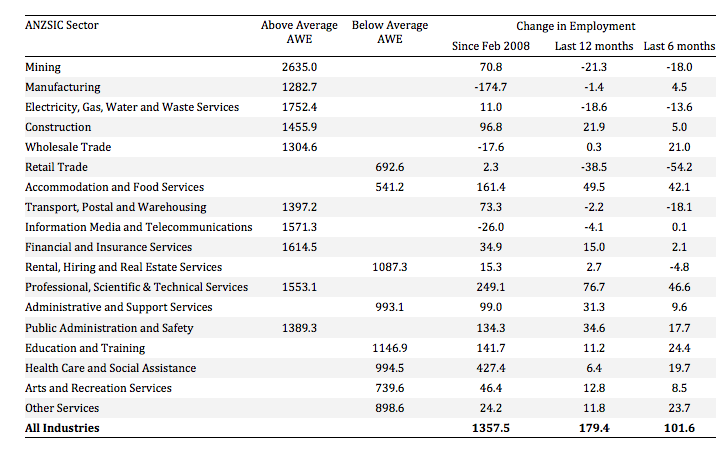

The next table shows the distribution of net job changes across industry for the three periods analysed matched with their place in the pay distribution.

Low-pay sectors (75 per cent or less of average weekly earnings) are Retail Trade, Wholesale Trade and Arts and Recreation Services.

The sectoral decline in Manufacturing, Wholesale Trade, Information, Media and Telecommunications is evident, losing employment since over this cycle, all above-average pay sectors.

In the last six months, there has been a sharp decline in employment in Retail Trade and Transport, Postal and Warehousing.

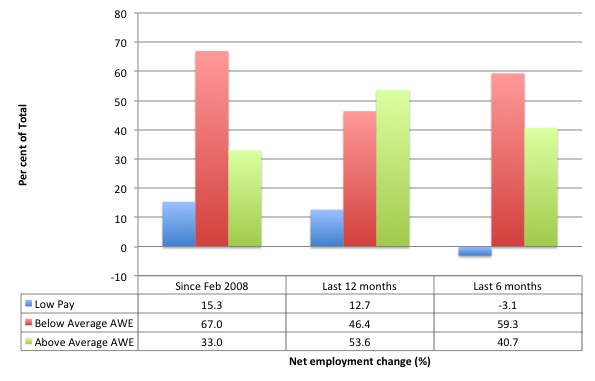

The following graph summarises the results for the three periods.

For the overall period since February 2008, which incorporates the slowdown after the GFC, the expansion on the back of the fiscal stimulus, and then the slowdown up until July 2016 as the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn and mining investment collapsed, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for 15.3 per cent of the total change in employment (at August 2016 these jobs accounted for 19.9 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 67.0 per cent of the total change in employment (at August 2016 these jobs accounted for 50.8 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 33.3 per cent of the total change in employment (at August 2016 these jobs accounted for 49.2 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

Over the last 12 months, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for 12.7 per cent of the total change in employment.

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 46.4 per cent of the total change in employment.

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 53.6 per cent of the total change in employment.

Over the last 6 months, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for -3.1 per cent of the total change in employment.

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 59.3 per cent of the total change in employment.

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 40.7 per cent of the total change in employment.

Overall conclusions from the analysis:

1. It is clear that in the more recent periods, the bias towards low-pay work has intensified along with the rising part-time ratio and the rising underemployment.

2. Over the last 6 months, there has been a disproportionate growth in below-average paying jobs. The decline in share of low-pay jobs is the result of the major decline in retail employment.

Conclusion

In a similar vein to the results I found for the US (albeit with slightly different research questions), the analysis of the Australian labour market over the last several years shows a bias towards the net creation of low-paid and below-average pay jobs, which would have to be considered a disturbing trend given the implications for long-term productivity growth and material prosperity.

This trend has intensified over the last 6 months.

So not only has Australia become a part-time employment nation, it is also heading the way of a low-pay nation with the commensurate negative impacts on productivity that will follow from that.

The race to the bottom that has been spawned by the simmering fiscal austerity in the face of weak non-government spending growth is now in full flow.

Far from being a clever nation, Australia is allowing its politicians to reduce our future prospects at a fairly alarming rate.

The conservatives constantly rave on about flexibility and choice when confronted with the reality that 86 per cent of jobs created in net terms over the last 12 months have been part-time.

But they cannot run that line when we understand that an alarming increase in underemployment has accompanied that trend.

And today’s analysis shows the disproportionate shift in that part-time work world towards below-average paying jobs.

Clearly, this analysis is at the aggregated 1-digit ANZSIC level and a richer story could be told if we used the two-digit and three-digit typed drill downs into the industry classification.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The race to the bottom that has been spawned by the simmering fiscal austerity in the face of weak non-government spending growth is now in full flow. Far from being a clever nation, Australia is allowing its politicians to reduce our future prospects at a fairly alarming rate. The conservatives constantly rave on about flexibility and choice when confronted with the reality that 86 per cent of jobs created in net terms over the last 12 months have been part-time.”

The electorate has voted for its own destruction.

The whole scam is neoliberal economics! Professor Joseph Stiglitz, John Ralston Saul. Steve Keen, and you professor, Michael Hudson and Professor Richard Wolff! We could list a whole heap of them still outcast by the mainstream! Fraud is so entrenched into the system it is hard for these people ever to get a voice as politicians and elected officials are influenced so heavily with this financialised global system! Any economists outside the system are cheapened and ridiculed by the media and planted trolls controlled by the mainstream economic mantra! Airtime is given significantly to mainstream economic dogma! You often see word for word narrative repeated from one mainstream outlet to the next across the globe with stories planted by the vested interests to keep the status quo! Sometimes I think this swill when they sleep they dream about the good old days when slaves were kept, now that was better than cutting penalty rates!

casual employment is becoming more rampant. Too easy for bosses to avoid Fair Work obligations (accumulate leave entitlements, sick leave, notice-periods and payouts), and also pressure is on to toe the line (eg NOT raise things like unsafe work practices, or lacking training) for employees to hold onto job. I know of company with numerous employees all with 12 months continuous full-time employment and still on casual classification. A LOT of flaky businesses forming whose model is margins subcontracting a casual workforce (eg cleaning) that would not otherwise stand up to any degree of financial diligence. It’s a jungle out there!

Dear Bill

You wrote that the Conservative Party gets most of its funding form businesses. I believe that political parties should receive enough public money to allow them to dispense with donations altogether. A generous fixed sum should be made annually to political parties. This sum should be divided among the parties in proportion to the votes received, while excluding parties which didn’t get 4% of the vote.

For instance, in Canada the sum could be 338 million dollars, 1 million for each constituency. If a party gets 40% of the votes cast for parties which passed the 4% hurdle, then it will receive 40% of that sum. Donations to political should still be legal, but there should be no tax advantage for them, and all donations should be public and posted on a website.

Elections aren’t really that expensive as a percentage of GDP, and complete independence of political parties from donations would eliminate one plutocratic contamination of democracy. 338 million would be just over 0.1% of the federal budget in Canada.

Regards. James

I have to stop reading this blog sometimes because of how confronting it can be about my future in Australia as a young Australian. Good analysis as always Bill.

Bill,

Are the part time/ underemployment trends you describe showing up in the income tax take yet?

In the UK the level of working tax credits and the newly coined JAMs (just about managing ) are indicative of the problems of insufficient jobs etc.

Dear Chrislongs (at 2016/12/01 at 10:46 pm)

Yes, indeed. Tax revenue is well below that projected in the fiscal statements. Another statement is coming soon and we will see what the government has to say then.

best wishes

bill

Dear Jordan (at 2016/12/01 at 10:07 pm)

We are relying on you as a young Australian to take action as a cohort and stop this rot continuing into the far distant future.

best wishes

bill

In Australia do you include the self employed as casual or is there a separate category. You may know that there have been and are being pursued cases to challenge the enterprise definition of self employment (e.g. Uber – successful challenge; Deliveroo – pending. There may be appeals). As you will appreciate it is difficult for authorities to enforce minimum wage rates (NLW) when work is handed over as transactions i.e. taxi journeys which will vary enormously in terms of completion times etc. I can confirm there is a race to the bottom even in the public sector with changes to T&C’s and pensions (no more final salary). I also feel the public sector has traditionally set the ‘gold’ standard in conditions and pay and obviously decline in that area may additionally accelerate the decline in the private sector.

To me the trend is from employment to jobs to work to task. From salary to pay to price to total piece work. Does that help?

Apologies my contribution is referring to the UK which I forgot to mention.

Where are the unions in all this?

Where there are unions, they seem to be more interested in feathering their own nests. There is evidence of corruption, even criminality. Unions seem more interested in political power than discharging their industrial duties.

Immigrants coming from countries without a union culture have weakened the system of unionized work and leave themselves prey to unscrupulous employers, with employers in many cases coming from the same countries as the exploited.

And now the 457 visa system is being rorted to the advantage of employers and to the disadvantage of mainly young Australians. I have a friend who has a son who applied for 300 accounting positions over a 3 year period, receiving acknowledgement of his application from only a handful of job advertisers over that period. He spent the 3 years washing dishes in a restaurant. Earlier this year, I read that over 5,000 accountants had been imported in the 2014/15 year. Go figure.

Henry, the unions need both members and political power to change industrial relations for the better. Both have fallen off in recent times. I’ve been employed by four companies over the last 10 years and each time I’ve been the only union member. It’s also an educational aspect – I asked my friend the other day if they have read their Award, they had no idea what I was talking about.

Quote:

.

I agree with the principle of doing away with donations, at least large donations from single sources.

And in principle, public funding would seem to be the way to go.

The UK does this to a very limited extent – so called “Short Money” (named after a politician surnamed Short, I believe). I think it only covers the official opposition, and probably only for their parliamentary activities.

.

The problem with allocating funds according to votes received, is that it will obviously favour already large and powerful parties, and disfavour small, new, struggling parties (which may be progressive in nature – of course, they could also be the opposite – extreme right-wing etc).

.

I’m not sure what the solution is, but I think you’d have to allow an element of legal donation, so long as it could be genuinely limited to small individual donations. But that would be tricky to enforce. Smart operators would find ways round it, and smaller parties would still be disfavoured.

.

As we see in the USA, both major marties are by now essentially just two different versions of neo-liberal orthodoxy, and many would hope to see the solution in some form of “third party”. (Mind you we now have a variety of “third parties” in the UK, and the results haven’t always been ideal). We saw that Sanders was quite successful in raising funds via crowdfunding….lots of small donations, and that seems like a way to go. But he was still running under the Democrat banner. Meanwhile Jill Stein was apparently unable to get airtime, which seemed to be her major problem (I don’t know how successful she was at fundraising).

.

Ideally though, democracies would get rid of all corporate political funding, and corporate lobbying, and in the UK, get rid of the corrosive “honours” system, whereby Lordships and knighthoods and the like are traded for influence. But no government or party is brave enough to do anything about it.

“..the unions need ………. political power to change industrial relations for the better..”

Matt,

I believe they have too much political power. This corrupts them and it corrupts our political system. It has corrupted the Australian Labour Party. What they need to do is get their house in order and focus on the multiplicity of industrial issues that need attention and winning credibility back.

Mike Ellwood, in Australia candidates who receive more than 4% of the first preference vote in their electoral division receive from the government about $2.60 per vote following the election. Donations from big business and other vested interests are however poorly regulated and the Liberals and Nationals receive the vast bulk of these. In my opinion donations should only be allowed from individuals with a cap on donations and real time disclosure as well as legislation to block all secondary funding methods. The 4% bar for government funding unfairly hampers legitimate micro parties and I would drop this to 1% as parties and candidates already undertake a registration qualification process.

Henry, in regard to trade and professional unions I feel they have performed a primary role in ensuring adequate wages and conditions that many of us still enjoy. Unions have been deliberately targeted by the neoliberal elites especially over the last 30+ years and have been relentlessly demonised and weakened whilst at the same time astronomical levels of price gouging, tax evasion and fraud by the business sector have remained unpunished. A balance of power is the best guarantor of fair outcomes for workers as well as genuinely democratic governments which unfortunately we no longer have due to the march of neoliberalism and the effective corporate control of governments at present.

Unions like our political representatives and governments are vulnerable to being led by self serving and corrupt individuals and the same solutions apply. Greater openness, legitimate media investigation and exposure, appropriate regulations, prosecution by the courts and genuine democratic elections and processes.