Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australia’s race to the bottom to part-time jobs with low-pay

To coincide with the US Bureau of Labor Statistics release of the May 2016 Employment Situation I updated my analysis on the pay characteristics of the net job creation in the US labour market – see Bias toward low-wage job creation in the US continues. The overwhelming finding was that the jobs lost in low-pay sectors in the downturn have more than been offset by jobs added in these sectors in the upturn. However, the massive number of jobs lost in above-average paying sectors have not yet been recovered in the upturn and do not look like being so, given the labour market is slowing again. In other words there is a bias in employment generation towards sectors that on average pay below average weekly earnings. In the last 12 months, 86 per cent of the net jobs added in the Australian labour market have been part-time and underemployment has risen, suggesting a rise in casual work as well. Further analysis in this blog reveals that this accelerated trend towards part-time employment creation has been accompanied by a disproportionate shift towards low-pay employment (and below-average employment in general). The shifts over the last 6 months, in particular, towards below-average employment has been alarming. So come on down to Australia as our politicians take us on a race to the bottom in the part-time nation with low-pay, that barely grows at all. We are a very stupid nation supporting the policy structures that deliver this poverty of outcomes.

Over the 12 months to July 2016, the Australian labour market added only 219.8 thousand (net) jobs. 190.1 thousand of them have been part-time – that is 86.5 per cent.

In that time, underemployment (part-time workers who cannot find enough hours of work to satisfy their desires) rose from 7.8 per cent (951 thousand persons) to 8.9 per cent (1133.7 thousand persons).

So there is now an extra 182.6 thousand workers who are in part-time employment but not working to capacity.

These trends have led me to refer to Australia as the ‘part-time employment nation – see Australian labour market – the part-time employment nation

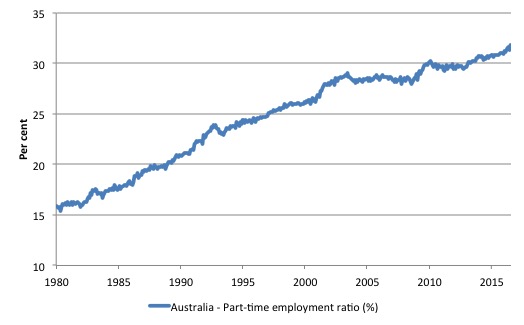

The following graph shows the acceleration of part-time employment over the three or more decades since 1980. In February 1978, 15.3 per cent of workers were part-time. This ratio had risen to 31.9 per cent by July 2016.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics does not collect data on ‘casual employment’ in the monthly Labour Force survey.

The (latest data for casual arrangements is for May 2104, when the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 21.6 per cent of the 9,898.9 employees at that time were causal.

Total employment in May 2014 was 11,503 thousand so the incidence of casualisation will be even higher.

Since 1992, the percentage of employees without paid leave entitlements (one of the several characteristics that define casual work) has risen from 21.3 per cent to 23.9 per cent in 2013 (latest data).

On average an underemployed worker desires an additional 15 odd hours per week – so the labour wastage implied by the massive number of unemployed workers is no trifling matter.

A question that you will not see answered in the usual press coverage is the pay characteristics of the net jobs being added to the Australian labour market.

It is one thing to say that Australia is becoming a part-time employment nation but another dimension worth considering is the trends in pay.

We know that the overall wages growth in Australia is at record low levels. But the employment trends within the distribution of average weekly earnings is also interesting.

That is what the rest of the blog examines.

The Australian employment by industry data can be obtained – HERE.

The average weekly earnings data by industry can be obtained – HERE.

In a related study I have done for the US economy – see US jobs recovery biased towards low-pay jobs and the updated version – Bias toward low-wage job creation in the US continues – the questions asked were slightly different.

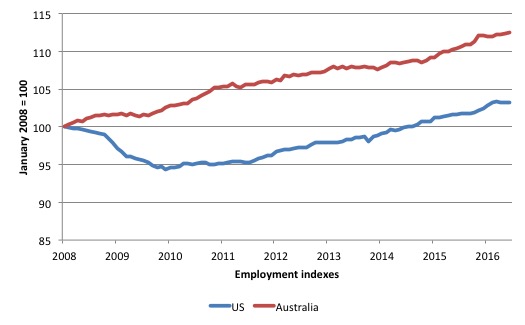

The following graph tells us why.

It shows total employment in the US (blue line) and Australia (red line) from the pre-GFC peak (January 2008) until June 2016.

In the case of the US, my analysis compared the number of jobs lost in the downturn up to December 2009 by their pay characteristics to the number of jobs gained in the upturn from the trough of December 2009.

That allowed me to conclude as in the introduction – that net job creation in the US has been biased towards sectors that on average pay below average weekly earnings.

Clearly an examination of the graph shows that the Australian path after the GFC began was more of a slowdown and as a result of of the early and large fiscal stimulus, employment continued to grow.

So for Australia I have examined three periods:

1. The period since the peak (January 2008) to July 2016.

2. The last 12 months.

3. The last 6 months.

Has the trend to low-paid jobs accelerated over those three time horizons? Is the dominance of part-time work over the last 12 months a sign of more low-paid jobs relative to higher paying jobs?

The following tables tell the story.

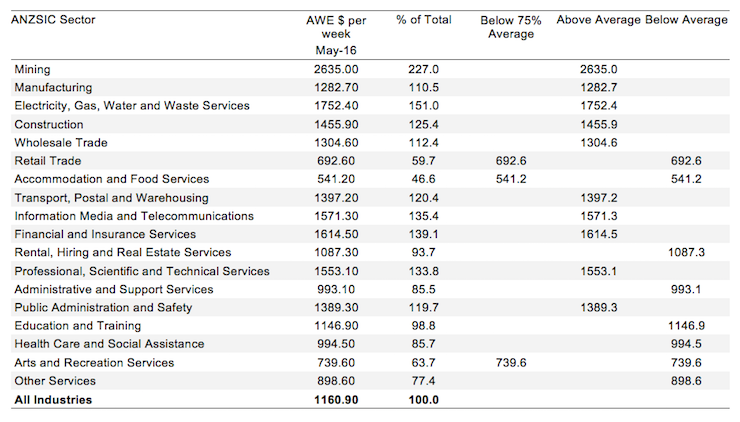

The first table looks at the industry distribution of total earnings as at May 2016 using the top level ANZSIC (Australian and New Zealand Standard Industry Classification).

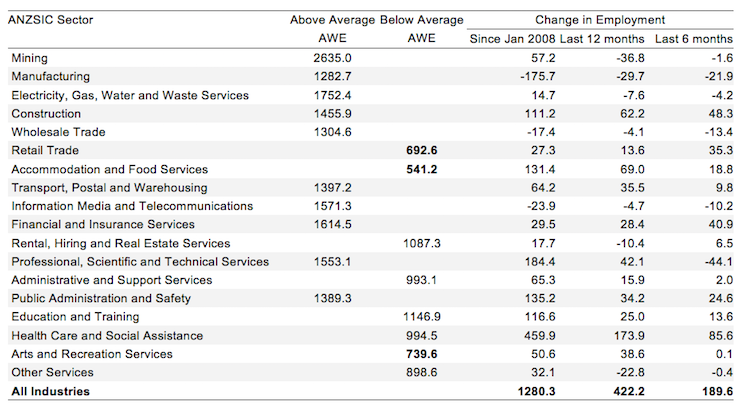

The next table shows the distribution of net job changes across industry for the three periods analysed matched with their place in the pay distribution.

The bold entries in the Below Average AWE column are those industry sectors that are 75 per cent or less of the All Industries AWE (that is, our low wage sectors).

The slowdown in the last 6 months is apparent as is the sectoral decline in Manufacturing, Wholesale Trade, Information, Media and Telecommunications.

There has also been a collapse in Professional, Scientific and Technical Services in the last 6 months, which is consistent with the declining full-time employment growth over that period.

These are all above-average paying industry sectors.

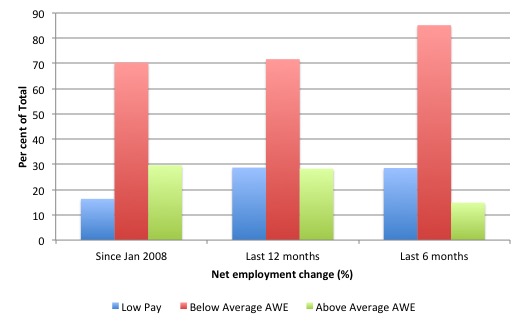

The following graph summarises the results for the three periods.

For the overall period since January 2008, which incorporates the slowdown after the GFC, the expansion on the back of the fiscal stimulus, and then the slowdown up until July 2016 as the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn and mining investment collapsed, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for 16.3 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 20 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 70.4 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 50.9 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 29.6 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 49.1 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

Over the last 12 months, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for 28.7 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 20 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 71.7 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 50.9 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 28.3 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 49.1 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

Over the last 6 months, the following results are found:

1. Low Pay sector jobs change account for 28.6 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 20 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

2. Below-average AWE jobs change account for 85.2 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 50.9 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

3. Above-average AWE jobs change account for 14.8 per cent of the total change in employment (at May 2016 these jobs accounted for 49.1 per cent of total non-farm industry employment).

Overall conclusions from the analysis:

1. It is clear that in the more recent periods, the bias towards low-pay work has intensified along with the rising part-time ratio and the rising underemployment.

2. Over the last 12 months, the low-pay jobs are being created in far greater proportion than one would expect from their overall place in the jobs distribution as at May 2016.

3. Over the last 6 months, the disproportionate growth in below-average paying jobs has been accentuated.

Conclusion

In a similar vein to the results I found for the US (albeit with slightly different research questions), the analysis of the Australian labour market over the last several years shows a bias towards the net creation of low-paid and below-average pay jobs, which would have to be considered a disturbing trend given the implications for long-term productivity growth and material prosperity.

This trend has intensified over the last 12 months and especially the last 6 months.

So not only has Australia become a part-time employment nation, it is also heading the way of a low-pay nation with the commensurate negative impacts on productivity that will follow from that.

The race to the bottom that has been spawned by the simmering fiscal austerity in the face of weak non-government spending growth is now in full flow.

Far from being a clever nation, Australia is allowing its politicians to reduce our future prospects at a fairly alarming rate.

The conservatives constantly rave on about flexibility and choice when confronted with the reality that 86 per cent of jobs created in net terms over the last 12 months have been part-time.

But they cannot run that line when we understand that an alarming increase in underemployment has accompanied that trend.

And today’s analysis shows the disproportionate shift in that part-time work world towards below-average paying jobs and, within that cohort, low pay jobs (less than 75 per cent of the All Industry Average).

Clearly, this analysis is at the aggregated 1-digit ANZSIC level and a richer story could be told if we used the two-digit and three-digit typed drill downs into the industry classification.

That sort of analysis is more time-consuming than is feasible for a blog post.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Any confirmation of drop in wages such as an increase in debt, reduced sales of basics or negative equity reduced net worth?

Same thing seems to be happening in Canada. Even the technical professions are affected. For example, a quick look at the job postings this morning reveals that a chemist specialising in analytical organic chemistry can expect offers of a whopping $15/hr, (if you have at least 5 years experience) for all of his/her hard effort and expense in getting enough education to pursue such a career. This isn’t quite a living wage here.

If you search cross country for postings of the once abundant professional positions, a person searching today only finds a few dozen scattered about on a good day, and usually they appear as temporary; hardly worth uprooting and moving hundreds or thousands of km for. There are people who refuse to give up hope and have been searching for years unsuccessfully for that first or second job.

I’m not sure a job guarantee by itself could turn this unfolding disaster around any longer. The marketplace itself needs resetting. There needs to be public credit available to the unemployed for startups, because they are in the best position to see the market failures and to see the real opportunity existing today, if only.. The large corporations really only understand how finance works now, and how to exploit that for the benefit of the few; and, that is a dead end for the real economy that the rest of us depend upon for all our needs.

It is every elected politicians duty to restore the health of the real economy. To do less is negligence.

I don’t contribute much here as its sort of over my head. Thought you may be interested in this though. Its from a Brisbane Australia property researcher on the same ideas as Billy writes above.

“’25 years ago there were five full-time jobs for every one part-time job. Today, that ratio – with the above statistical skulduggery included – is two to one. And little old me thinks – when you measure full-time as someone who works 40 hours a week for the same company and with the appropriate benefits – that proportion is closer to 50-50.” He has a good Graph too.

http://us8.campaign-archive1.com/?u=1c5572de85655446f0c283f04&id=68834ffa99&e=beea0bf23d

Cheers Punchy

@J Christensen: the “system” is getting worse. The race to the bottom in a globalised world seems to be the root cause. I agree that the amoral transnational corporations have relentlessly driven this race to the bottom with only the executive elite being immune from this pernicious trend.

Barri Mundee: I agree; the elite are not doing global trade well at all. This is all supported by faulty economic ideas.

No one is really immune in a world were poverty has become the chief product though. The brain dead managerial class will be the last to understand that cost cutting is no replacement for developing new sales opportunities.

All this talk of a race to the bottom in an globalised world is just pointless. You can stand there and bleat this for the next 50 years and it wont make one iota of difference. The global supply of labour, and educated intelligent labour in increasing and as much westernized Keynesians think they can totally engineer around the laws of supply and demand, so that working populations in western nations can sit in their little comfy deluded worlds and expect to fell no pain, it aint going to happen chaps, dream on. There are limits to everything. Whether a Keynesian likes it or not there is 2 billion people in India and China , rapidly getting educated along with their economies rapidly industrializing. This idea that people in the West have that the world owes their perfect well paying job just because they went to university is stupid beyond belief. What holds true in the world of products holds true in the world of labour as Bates Clark rightly pointed out. If mate in Canada wants to earn more than $ 15 per hour, do a degree the market wants like technology or computer programming, don’t do the degree you want and then expect the world to deliver you up the reward you think it should be.

If you really want to do something to help our westernized workforces, we need to embrace raising productivity which means learning skills through our lifetimes that allow technology to be incorporated more into the work patterns to increase output and diversity of products produced which in turn will help entrepreneurs to open up innovative markets for new products. Capital + labour + technology = wealth of which a worker should get a fair share, same formula as when Adam Smith was around. The labour in that equation intrinsically is becoming worth less without education, so people have to work smarter and learn more. That’s just life. Instead of being adults and telling our kids this and preparing them, we teach them , hey the world owes you something and even more so if you have done a degree at a uni.

Dear Paul Farmer (at 2016/09/01 at 12:48 pm)

If you were correct then how do you explain the increasing share of national income to profits (in most countries) and the increased inequality in the size (personal) distribution of income such that the top 10 per cent have almost exclusively appropriated all the growth dividends in the last several years.

best wishes

bill

Paul farmer (Sept 1, 12:48pm),

Not to diminish Prof Mitchell’s point; however, the job advertisement itself is a good indication that there is a market for the advertised qualification. The employer just feels it can get away with $15/hr (That figure is no joke. That is what the ad says) An analytical chemist is the sort who works in a lab. Since they are advertising a position in Canada, it does not appear that the job can be practically off shored to India or China etc.

The person who will fill that position had to pay North American size tuition to become qualified, and has to pay North America size rent and grocery bills etc.. So were are the North American size wage offers? That people are paid relatively less in dollar terms elsewhere is immaterial.

With all of these people in the world there is a great deal of work to be done if we want to avoid returning to stone age living conditions. There has to be equitably distributed and adequate money available to allow all the trade in skills and labor effort to make that possible.

Turning off the spigot while a handful of people sit on all the money watching the economic cogs grind to halt, for the sheer fun of it, is not an option for a sovereign money issuing government.