In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Trump might do us a favour – expose the myth of central bank independence

Prior to the ‘surprise’ victory of Donald Trump in last week’s US Presidential poll, there was an article (September 28, 2016) in the Financial Times – Trump is right to take aim at the ‘political’ Fed – arguing that Trump had “broken a cardinal rule in US presidential campaigning by openly questioning the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve”. In the Presidential debates, Trump had claimed that the US Federal Reserve banks had been “doing political things” as a result of their low interest rate policy and creating a “false economy”. The central bank governor responded by saying the bank did not take politics into account when changing monetary policy. Apparently, Trump was echoing conservative economists who think the low interest rates have pushed investors into riskier financial investments, which will crash if rates rise. It has to be said that history tells us that Republican party politicians regularly lambast the US central bank along conspiratorial lines (for example, 2011 Rick Perry’s “treasonous” allegations against Bernanke; George W Bush, Richard Nixon). What does it all mean? There was an interesting article in the Financial Times today (November 14, 2016) by Wolfgang Münchau – The end of the era of central bank independence – that claims the tide is shifting and more political interference in monetary policy is to be expected. My conclusion: if so, good. Democracy requires the elected polity takes responsibility for economic policy rather than an unelected, largely unaccountable, group of ‘economists’. But, I also add, the idea of central bank ‘independence’ is one of those neo-liberal myths that allow the elected polity to disassociate themselves from bad economic policy.

So the mainstream economists and many financial commentators are up in arms about the inroads into central bank independence (whatever that is!) as a result of Donald Trump’s ridiculous elevation to President-elect (not to be read as an implicit vote for his opponent – never!).

Wolfgang Münchau also notes that the British Prime Minister ahs also impugned the integrity of the Bank of England’s independence since she took over from Cameron following the Brexit vote.

He is correct in saying that:

At this stage we do not really know what the presidency of Donald Trump will mean. We do not even know exactly what Brexit means.

Except that the scaremongers are in full speed ahead mode and, in Britain’s case, have been since the end of June. There is one thing that we surely know about – the mainstream media seems to have lost its clout, given its overwhelming support for Britain to remain and for Hillary Clinton in the US election.

The mainstream media (including UK Guardian and the New York Times) couldn’t get enough anti-analysis in both instances into their publications every day. And the scale of fear was progressively elevated over time.

So in the UK it reached the point where Brexit was apparently going to cause cancer (Source among others).

In the US election, we now have the extraordinary confession by the New York Times that it “blew it on Trump” and the editor claimed the newspaper would now “rededicate … [itself] …to the fundamental mission of Times journalism. That is to report America and the world honestly, without fear or favor” (Source).

The New York Times coverage was a total disgrace – totally biased towards the establishment that it serves.

Anyway, back to central banking.

Wolfgang Münchau thinks the election (and the Brexit vote) means that we are:

… approaching end of the age of central bank independence; and, as a concomitant, the loss of influence of academic macroeconomists.

Taking his construction at face value for now, if both of these contentions turn out to be accurate, then the world will be better off by far.

The face value part is that the assumption that there is central bank independence at present which is under threat is also contestable as we will see.

Wolfgang Münchau says:

Central bank independence is premised on two conditions. The first, and more important, is that there is a broad consensus on the goals of monetary policy. The second is that an independent central bank board, usually staffed by professional economists, can deliver those goals. The first of these conditions is broken. The second is under a cloud.

Taking a step back, what exactly do economists mean when they talk about central bank independence?

Like most things associated with mainstream economics, the the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

Their use of language is rarely meaningful to those outside the inner sanctum. They exploit this capacity to be obscure by then allowing (prodding) politicians to use economic terms in ways that are both ideologically slanted and at odds with the initial conceptualisation.

So it goes for central bank ‘independence’.

It is one of the several strands that form the mainstream neo-liberal attack on government macroeconomic policy activism.

We get assailed continuously by economists talking about the need for deregulation (particulary of labour and financial markets) on the basis of ‘freeing up’ commerce. We have come to understand that this means nothing at all to do with societal freedom.

Rather it is code for giving capital more freedom to exploit its already powerful position in order to extract more real income from workers and consumers with no societal advantages forthcoming.

Stuff about sovereign debt crises are often wheeled out to disabuse us of government debt, despite that same debt being craved (and demanded) by financial market players who know full well it is risk-free and therefore a low cost benchmar on which to price the risk of their other assets and products.

As long as the deficit spending is going in their favour they shut up. But if it looks like helping the hoy polloi these elites scream ‘sovereign debt crisis’, waste, insolvency and all the rest of it. They are shameless hypocrites.

And then another faux agenda – the demand that central banks should be independent of the political process.

There has been a huge body of literature emerge to support this agenda over the last 30 odd years. The argument for so-called ‘central bank independence’ is always clothed in authoritative statements about the optimal mix of price stability and maximum real output growth and supported by heavy (for economists) mathematical models.

If you understand this literature you soon realise that it is just another ideological front in the political fight against discretionary macroeconomic policy interventions by elected governments.

The mathematical models that are used to ‘prove’ the worth of ‘independence’ are not at all useful in describing the real world. They have no credible empirical content and are designed to hide the fact that the proponents do not want governments to do what we elect them to do – that is, advance general welfare.

The central bank ‘independence’ agenda is also tied in with the growing demand for fiscal rules which will further undermine public purpose in policy.

Take a step back and consider that the Japanese government 10-year bond yield is currently at -0.03 per cent. It is not the only 10-year bond selling at negative yields – which means that ‘investors’ are prepared to park funds in the central bank (effectively) and pay for the privilege.

That tells you that all the scaremongering that has been going on over the last twenty years about hyperinflation, the Japanese government running out of money, the bond markets dumping the yen, and the rest of it were self-serving lies designed to advance a particular ideological position at the expense of the broader social well-being.

The falling yields on government debt have defied the mainstream financial understanding. The bond yields have moved in the opposite direction to that predicted by many mainstream economists, blinded by their irrelevant textbook theories about how markets work.

In that neo-liberal textbook fairyland, the yields should be sky high now, inflation should be accelerating out of control and the Japanese government among others would have been forced to admit they had run out of money.

None of these predictions have been remotely realised. Students of macroeconomics are continually being taught a myth, which is detrimental to their education and life experiences.

Many turn into the future doomsayers and sociopaths in organisations such as the IMF, the European Commission and other like policy making institutions.

Some go onto to gain membership of central bank boards and to reinforce their status they rave on about the need for more central bank independence to insulate monetary policy from political decision-making as if that will foster the well-being of the population.

The idea of central bank independence is a sham and there is ample evidence to support that view.

Central bank independence is part of the grand myth that governments cannot be trusted not to create accelerating inflation as a result of political machinations overriding economic responsibility.

The mainstream Monetarist literature, which emerged in the 1970s, promoted the idea of central bank independence because it was a way to take policy discretion from the democratically elected governments and thus reduce the scope of government economic activity.

It was part of the plan to privatise, deregulate and shift the balance of power to the top-end-of-town after years of social democratic decision making in the Post World War II period.

The concept of ‘dynamic inconsistency’ entered the nomenclature with the Monetarists and highlighted the virtue of so-called monetary rules – where the central bank would announce, say, an inflation target and then adjust policy (interest rates) rather mechanically to keep inflation within the announced band.

The claim was that if the central banks were insulated from ‘political’ influence then the ‘markets’ would form the view that the policy stance was credible and would form expectations accordingly.

An additional claim was that independence would help transparency – another factor meant to establish credibility in the monetary policy stance.

Wolfgang Münchau says that:

The consensus of 1989-2016 – the golden age of financial globalisation – held that central banks should target a low positive rate of inflation. This was supported by macroeconomic theories developed since the 1980s. It seemed natural that a new breed of economists, trained in a newer generation of economic models, would deliver the goals society wants them to deliver, free from the pressures of day-to-day politics.

When there are rich consultancies on offer, you can bet the mainstream economists won’t rock any boats!

Former US Federal Reserve chairperson, Ben Bernanke gave a speech – Central Bank Independence, Transparency, and Accountability – to the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies International Conference, hosted by the Bank of Japan in Tokyo on May 25, 2010.

He spoke about ‘credibility’:

However, a central bank subject to short-term political influences would likely not be credible when it promised low inflation, as the public would recognize the risk that monetary policymakers could be pressured to pursue short-run expansionary policies that would be inconsistent with long-run price stability. When the central bank is not credible, the public will expect high inflation and, accordingly, demand more-rapid increases in nominal wages and in prices. Thus, lack of independence of the central bank can lead to higher inflation and inflation expectations in the longer run, with no offsetting benefits in terms of greater output or employment.

First, he claimed earlier in the speech (correctly) that “monetary policy works with lags that can be substantial”. This is because it operates, principally, via changing short-term interest rates, which then have to feed through the term structure, and then interest-rate sensitive spending decicions have to change.

There is huge uncertainty involved because a rising interest rate helps some and hinders others. There is very little robust work that has been done to show categorically that the winners are overpowered by the losers (so rising interest rates stifle demand).

But the point is, how effective will “short-run expansionary policies” be if there are substantial lags.

Second, the expansion of bank reserves has been quite a characteristic of the monetary policy response to the crisis. This expansion has violated all the mainstream beliefs – erroneous as they are. It hasn’t been inflationary. It hasn’t increased bank lending. It hasn’t led to an acceleration in inflationary expectations.

Since the onset of the GFC, we have lived through a fundamental shift in central bank balance sheets and the question the mainstream economists haven’t been able to answer is: Why haven’t private agent expectations adjusted so that they are demanding “increases in nominal wages and in prices” to insulate themselves from inflation?

Answer: Bernanke’s view relies on the flawed mainstream idea of ‘rational expectations’, which claims that individuals (us) actually have perfect knowledge (errors average to zero) of the economic processes driving the real world and will immediately adjust our expectations of inflation upwards if bank reserves increase.

The theory is logically inconsistent and has no empirical content at all. It is a far-fetched theory devised by ideologues to hide their contempt for government intervention in some ‘hard’ mathematics.

Bernanke also represented the mainstream position by saying that:

… a government that controls the central bank may face a strong temptation to abuse the central bank’s money-printing powers to help finance its budget deficit … Abuse by the government of the power to issue money as a means of financing its spending inevitably leads to high inflation and interest rates and a volatile economy.

Question: the QE policy position has pumped massive volumes of currency into the banking system. While QE might operate via the secondary bond market, the impact on the banks is no different has the central banks been buying the public debt directly (via the primary issue).

No accelerating inflation and inflationary expectations are stable (if not on a downward trend) has been the result.

Exactly the opposite to that predicted by the mainstream economists.

Further, Bernanke’s point is, in fact, the reason why governments should directly control the central bank to avoid issuing debt. The point is that it is the act of net spending in a fiat monetary system that drives aggregate demand and exposes fiscal policy to the risk of inflation. The monetary operations (the central bank liquidity management) do not increase or reduce this risk.

So if the government just leaves the net spending impact on the cash system as reserves (earning nothing) that doesn’t increase the risk of inflation resulting from the spending in the first place, relative to if they drain those reserves by offering an interest-bearing public bond.

From a MMT perspective, the concept of central bank ‘independence’ is anathema to the goal of aggregate policy (monetary and fiscal) to advance public purpose. By obsessing about inflation control, central banking lost sight of what the purpose of policy is about.

Inasmuch as central bankers think they are independent, they advance the ideology that monetary policy should not be focused on advancing public purpose and requires fiscal policy to be subject to an austerity bias (so as not to conflict with the anti-inflationary stance).

But trying to control inflation with unemployment, which is more or less what Monetarism is about (however, ineffective it might have been over the years) is not consistent with advancing public purpose.

Even if increasing interest rates disciplines the inflation process (a contested idea), the costs of inflation are much lower than the costs of unemployment. The mainstream fudge this by invoking their belief in the Non-Accelerating-Inflation_Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) which assumes these real sacrifices away in the ‘long-run’.

Bernanke later on in his speech addresses the degree of independence:

I am by no means advocating unconditional independence for central banks. First, for its policy independence to be democratically legitimate, the central bank must be accountable to the public for its actions. As I have already mentioned, the goals of policy should be set by the government, not by the central bank itself; and the central bank must regularly demonstrate that it is appropriately pursuing its mandated goals.

This is the nub of the issue. When does the public actually get to elect the central bank board? Answer: never.

And with interest rates playing the bogey person role in modern economies given the dependence in the private sector on debt, changes in monetary policy carry political messages for that the elected government has to sanitise.

The point is that this approach to policy-making forces fiscal policy to adopt a passive role. If it doesn’t then it will be seen to be working against the rigid application of the monetary policy rules. The consequences of that have been the persistent labour underutilisation that has plagued advanced nations for 40 years, even during periods of economic growth.

While the central bank ‘independence’ mantra has acted as an effective discipline on fiscal policy (restricting deficits etc) to the detriment of workers and lower-income recipients, the data doesn’t suggest that this era of ‘independent’ central banks has made much difference to the stated targets of the exercise.

The current expected price inflation for the next 12 months derived from the Cleveland Federal Reserve’s – Inflation Expectations – series is 1.75 per cent, and even lower for a 10-year ahead horizon (1.69 per cent).

The the US Federal Reserve doesn’t publish a strict inflation target, they aim to maintain the inflation rate at 2 per cent per annum.

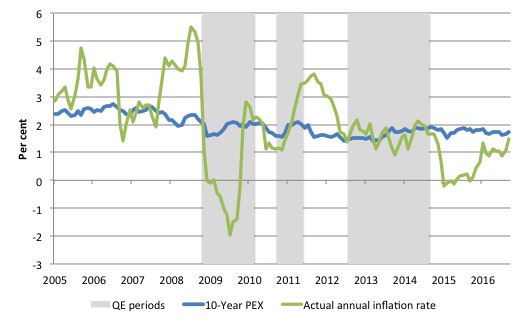

The following graph shows the evolution of the actual consumer price index and the Ten-year ahead inflation expectations series from March 2005 to September 2016.

Despite major US Federal Reserve action in the secondary bond markets, longer-term expected inflation hasn’t budged since 2009 and remains on a slight downward trend.

In fact, if the actual inflation rate, however measured (via the BLS CPI survey or via the PCE measures from the National Accounts), remains at their current low levels, then the expected inflation rate will drop further.

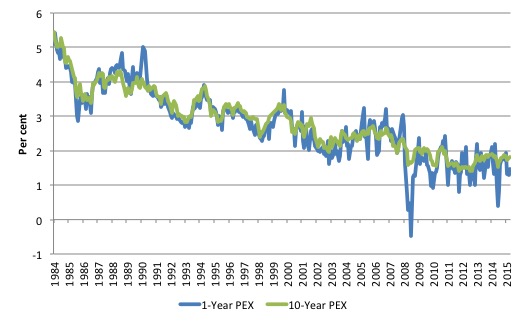

The next graph shows the history of the Cleveland Reserve Bank’s 1-year and 10-year price expectations series from 1984 to September 2016.

Prior to the crisis, inflationary expectations were nudging upwards and have since declined rather sharply and remain on a downward trend.

The decline (as noted above) has been associated with a major shift in central bank policy interventions, which should have pushed long-term inflationary expectations up significantly.

What is the evidence that central bank ‘independence’ delivers superior inflation results?

The so-called Cukierman index of CBI is widely used and “assesses the fulfillment of 16 criteria of political and economic independence using a continuous scale from zero to one, with higher values also indicating higher CBI. The overall index is based on a weighted average of the individual criteria” (Source)

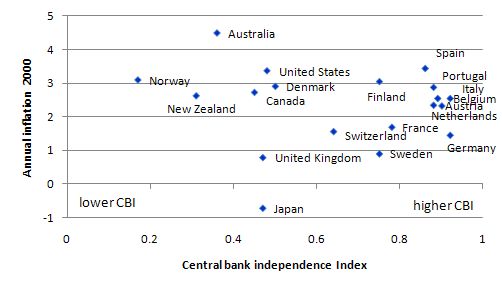

The following graph uses the values of the CBI index for the year 2000 and plots inflation against it for various countries. This is not a robust test of the hypothesis but visually nothing is happening to suspect that nations with more CBI (as measured) have lower or higher inflation rates.

I could have presented the data for any year with similar results.

The more robust empirical work on the subject delivers mixed results and the methodologies are highly compromised.

First, they usually cannot control for other factors which might explain differences in inflation performance across countries. Studies that have gone to some trouble to introduce credible control factors typically find no role for CBI in controlling inflation.

Second, there are the so-called ‘endogeneity’ problems. The studies tend to treat the CBI index value as exogenous (that is, given and not influenced by other factors in the models). It has been shown that nations that have high levels of ‘measured’ CBI also introduce policies that focus on austerity.

In other words, if the political factors supporting the push for austerity were absent, you would not get any traction by making the central bank independent.

The conclusion that I have reached from studying this specific literature for many years is that there is no robust relationship between making the central bank independent (in the way the mainstream use this term) and the performance of inflation.

Trump comes along …

The Monetarist mantra has dominated the conduct of macroeconomic policy for the last several decades, despite the resort to pragmatism in the early days of the GFC, when policy makers suddenly expressed a new found preference for fiscal interventions.

This was mostly because the elites knew that fiscal policy could bail them out of their disastrous situations. As soon as that was accomplished the disdain and misinformation about fiscal policy resumed in force.

But Wolfgang Münchau now thinks that:

The consensus of 1989-2016 – the golden age of financial globalisation – held that central banks should target a low positive rate of inflation. This was supported by macroeconomic theories developed since the 1980s. It seemed natural that a new breed of economists, trained in a newer generation of economic models, would deliver the goals society wants them to deliver, free from the pressures of day-to-day politics.

Donald Trump is not the first to contest this ideological consensus. But he is probably the highest profile critic in recent years.

Wolfgang Münchau thinks that this shift in public dialogue might “see 2016 as an economic policy inflection point”.

If it is a turning point then we can only be happy about that.

Flushing out the ‘independence’ farce into the open would be a socially useful impact of Mr Trump.

Governments are going to have to use fiscal policy more actively if they are to avoid a further financial collapse. Exposing the independence myth for what it is – an ideological ploy to restrict fiscal policy expansion (except when it helps the elites) – is a good thing.

Wolfgang Münchau agrees “with those who argue that central bank independence is neither necessary nor sufficient for price stability.”

He also thinks that the ‘independence’ “consensus has broken down” and this:

… alone means that monetary policy can no longer be relegated to independent experts. It should, and will, revert to what it was in many countries before the 1990s: an integrated function of a government’s broader economic policy.

How that plays out in the Eurozone, with the rabid German mentality in this regard will be interesting.

The ECB has really been playing a de facto fiscal role anyway, given their ill-judged decision not to create a federal fiscal authority.

But it has all been smoke and mirrors – as the bank reserves have been pushed up – the ECB has been claiming it has been just ensuring it can manage its interest rate target. That has been a blatant lie – it has, in fact, been funding government deficits and then forcing the same governments to impose austerity – thereby defeating the purpose.

Elsewhere, the smoke and mirrors might be pulled down more quickly.

Wolfgang Münchau says that

The first stage would be the appointment of politically compliant governors, and members of monetary policy boards more political than the current academic crop. This is how Mr Trump and Mrs May will subvert the system, not necessarily through the formal abolition of the concept of the independent central bank.

I have written about this issue before:

1. Central bank independence – another faux agenda

2. The sham of central bank independence

Conclusion

In fact, I would go much further than the suggestions advanced by Wolfgang Münchau.

There is, in fact, very little need for a separate structure called a central bank.

A progressive position (consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)) would merge the central bank with the treasury.

This would release thousands of bright former central bankers via retraining into the workforce to use their brains doing something useful, and also dismantle the public debt issuance machinery, which works against governments pursuing public purpose because the public debt is a primary target for negative politicisation – aka peddling lies about government insolvency.

Fiscal policy would become the dominant tool for stabilising the economic cycle and sustaining full employment and short-term interest rates would be set at zero.

Please read my blog – The natural rate of interest is zero! – for more discussion on this point.

Stable inflation would be rendered consistent with full employment via a Job Guarantee.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Is there such a thing as ‘exogenous money’?

John T. Harvey

“Thank you for posting a reply, M. Again, however, I’m afraid I don’t see a direct answer to my question. I asked what mechanism in the real world the Fed has available to raise money supply above money demand (something that you said above is necessary if inflation is to occur). Money supply can rise if the Fed buys assets or if loans are made from available reserves. To my way of thinking, neither of these can occur without the full and conscious participation of the other side of the transaction. Hence, the supply of money cannot be increased in the absence of demand.

Yet you say (above) that inflation only occurs when money supply is in excess of money demand. You have defended this with analogies, but not with real-world examples of the underlying process. I am a huge fan of using analogies to get the essential idea across; however, unless these mirror something that is going on in the real world (and in a very real and tangible sense), then recommending policies based on such stories is dangerous to say the least.

I hope you don’t think I’m being rude, but I think this is a key question and one that I have never found a monetarist able to answer: how is it in the real world that the central bank raises money supply above money demand? Can you please tell me this and in the context of actual Federal reserve policy tools?

This is not a trivial question. The entire monetarist superstructure rests on it. If the answer is that in reality this cannot happen, then I’m not sure how the rest of the monetarist analysis survives.”

Andrew Jackson certainly proved that politicians being in control of the central bank wasn’t necessarily a good thing.

http://michael-hudson.com/2015/10/how-the-u-s-treasury-avoided-chronic-deflation-by-relinquishing-monetary-control-to-wall-street/

As far as the NY Times going to, “rededicate … [itself] …to the fundamental mission of Times journalism. That is to report America and the world honestly, without fear or favor” Bull hockey, the rag will always serve its masters.

“As long as the deficit spending is going in their favour they shut up. But if it looks like helping the hoy polloi these elites scream ‘sovereign debt crisis’, waste, insolvency and all the rest of it. They are shameless hypocrites.”

“The central bank ‘independence’ agenda is also tied in with the growing demand for fiscal rules which will further undermine public purpose in policy.”

“The mainstream Monetarist literature, which emerged in the 1970s, promoted the idea of central bank independence because it was a way to take policy discretion from the democratically elected governments and thus reduce the scope of government economic activity. It was part of the plan to privatise, deregulate and shift the balance of power to the top-end-of-town after years of social democratic decision making in the Post World War II period.”

“Second, the expansion of bank reserves has been quite a characteristic of the monetary policy response to the crisis. This expansion has violated all the mainstream beliefs – erroneous as they are. It hasn’t been inflationary. It hasn’t increased bank lending. It hasn’t led to an acceleration in inflationary expectations.”

“The conclusion that I have reached from studying this specific literature for many years is that there is no robust relationship between making the central bank independent (in the way the mainstream use this term) and the performance of inflation.”

“The Monetarist mantra has dominated the conduct of macroeconomic policy for the last several decades, despite the resort to pragmatism in the early days of the GFC, when policy makers suddenly expressed a new found preference for fiscal interventions. This was mostly because the elites knew that fiscal policy could bail them out of their disastrous situations. As soon as that was accomplished the disdain and misinformation about fiscal policy resumed in force.”

………….

A very powerful article. Revolutions have been started for less and given that globally tens or even hundreds of millions of innocent victims of neoliberalism, off shoring and austerity could have instead lead rewarding lives if their governments simply had competent macroeconomic and social policy, the guillotines should be running 24/7. Jail is however a more civilised approach and neoliberalism has fortunately built many appalling private jails which can now be put to good purpose. I am sure many appropriate prison guards can be found from those beaten down by neoliberalism or imprisoned due to poverty.

If I were prone to believe in conspiracy theories.

Trump is the perfect establishment president for the times.

What better anti establishment leader than a born elite

parasitic speculator.Much the same with the leading Brexiters.

If the peasants are revolting we best get that directed in a way

which will not undermine our control of real resources .

As long as the state does not use its’ monetary soveirgnty to undermine

the elites wealth and power claims on the ‘independence’ of the central

bank can be tolerated.

Bill, the Independent did not say that Brexit would cause cancer. They said that cancer funding would be in doubt. The reason they said that is that a good bit of UK research is funded by Brussels and that, should it decrease or disappear altogether, there is little indication from this government that the funding would be replaced by anything comparable. It might, of course, but one should not count on it, given this government’s neoliberal predilections. We both know that there is no economic reason for the UK government not to replace EU funding by comparable UK funding. They probably could not let it go altogether, but it might be anemic. We will see, maybe, on November 23rd.

Is there an example of a political leader in any of the western democracies who is “progressive” and works for the public good, who understands MMT and is not afraid to say it publicly? Even Sanders, who was advised by Stephanie Kelton, did not do this during his campaign for the Democratic nomination.

My recollection of the (mostly right wing) criticisms of the Fed and the calls for an audit were not arguing that the Fed should be less independent, but that they were being controlled by the Administration to serve a political purpose. In essence, they seemed to be calling for more independence. OR, maybe they were actually calling for it to be eliminated and move to a gold standard w/no central bank. In either case, I don’t think they represent an MMT perspective, even accidentally. Will happily stand corrected if that is a mis-interpretation.

In the UK the mainstream media was not in any way completely anti-brexit. The Guardian is read by liberal lefties like me and not paid much attention to by anyone else. Far more widely read and influential papers were strongly pro-Brexit – The Sun, The Daily Mail, and The Daily Telegraph. These are unashamedly right wing. The broadcast media has to try and be impartial and balanced in its coverage but research has shown that they often follow these papers’ leads – ie the story of the day comes from them. The Tories have known how to use this to their advantage in election campaigns. However this didn’t work for the Tory leadership in the EU referendum coverage as for once they were on the opposite side to The Daily Mail.

You are unlikely to see any candidate trying to promote MMT directly – that would just invite “piling on” by the pundits, drowning out the message in a flood of derision and neoliberal propaganda. Sanders’ approach was optimal – outline a plausible approach to “pay for” spending increases, and wait until in office to explain that “deficit is good”.

People can understand the idea of “fiscal stimulus” without necessarily thinking of it in terms of deficit & debt. It is more important to mobilize support for spending than for deficits – spend the money and the deficits take care of themselves (absent legitimate efforts to cut spending or raise revenue elsewhere).

Richard Murphy (who does understand MMT) was advising the Corbyn team at one point.

[Bill notes: deleted link to Murphy interview. He does not “understand MMT” and is not worth promoting via this blog]

.

I’m not sure why, but Murphy and the Corbyn team seem to have parted company, and as we know, John McDonnell has been making very un-MMT-like noises. This may be because he doesn’t want to be seen to be associated with “printing money”-type policies. Or maybe because he doesn’t “get it”. I don’t know which it is.

Mike Ellwood, I have spoken to McDonnell and he has said he gets it but then goes and says things that indicate he doesn’t. I honestly think he doesn’t get it.

@Bill

.

Sorry Bill. I haven’t heard/read his full views on MMT, but the bits and I had heard/read seemed ok, and he has certainly said that he supports MMT more than once in his blog (e.g. in a critique he made of the PM proposals).

.

Without meaning to promote RM, can you briefly sum up what he gets wrong?

.

Do you happen to know of any British or British-based economists with a public profile who do understand (and support) MMT? RM was the only one I had come across, so it’s sad if he doesn’t understand it after all. Perhaps you object to his enthusiasm for tax. I’ve just received his 2015 book on tax (title edited out, before Bill does it for me 🙂 ) , which I ordered to try to get a better idea of where he was coming from, but haven’t got far with it yet.

.

.

.

.

Thanks Larry. Interesting (if depressing).

If Trump knows anyone who’s not a Monetarist, they’re likely Austrian or Libertarian.

It’s true Trump brings a certain flexibility to the table. But he also brings colossal ignorance. This is a man who doesn’t read, he gets his information from television.

So maybe if MMT can produce a hit TV show, Trump might give it a whirl.

Trump as an alternative to neoliberalism?

I know the left has had a lot of setbacks for many decades but this some straw to

be clutching.

Lyle, if they were arguing for removing the central bank due to wanting to go back on the gold standard, they don’t know their history. They would do well to read why McAdoo set it up in the first place in 1913. And the gold standard proved to be a disaster. I don’t know what to say about these people.