These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Helicopter money is a fiscal operation and is not inherently inflationary

There was a Project Syndicate article (September 2, 2016) – The Unavoidable Costs of Helicopter Money – claiming that “In fact, there are major downsides to helicopter money”. Hmm. Should I read this article was my thought at the the time. Waste a few minutes of my life. I wondered if I could pen the article in advance and then check to see how close I was. The theme would be inflation. In that I was correct. But the author really innovated a bit and, in doing so, undermined his own argument. What we learn is fairly straightforward. If a government continues to increase nominal spending growth ahead of the growth in productive capacity then there will be inflation. The argument presented is, in fact, nothing to do with the monetary operations that accompany government spending – helicopter or otherwise. The inflation risk is in the spending. If private investment expenditure outstripped the capacity of the supply-side to produce the capital equipment demanded then the same outcome. Should we caution against such expenditure? Should be make it taboo? Obviously not.

The Project Syndicate article (cited above) by banker Michael Heise asserts that:

What hasn’t changed is that embracing helicopter money would be a very bad idea.

What is helicopter money?

I have discussed helicopter money previously:

1. Keep the helicopters on their pads and just spend.

2. Overt Monetary Financing would flush out the ideological disdain for fiscal policy.

3. Overt Monetary Financing – again.

4. OMF – paranoia for many but a solution for all.

Heise’s description:

… helicopter money is newly printed cash that the central bank doles out, without booking corresponding assets or claims on its balance sheet. It can come in the form of cash transfers to the public or as the monetization of government debt; in both cases, it is a permanent loss for the central bank.

This is misleading.

First, newly printed cash (currency notes) is not typically the way that governments spend. Governments spend by crediting bank accounts (and in some cases sending out cheques to recipients), which then are deposited in bank accounts.

Either way, the printing presses are silent!

No printing presses or coin stamping machines are involved. Progressives should stop using the term ‘printing money’ when discussing these matters, even if they make finger gestures as they speak to indicate the term is in inverted commas!

Second, there is no sensible meaning to the idea that if the central bank credits bank accounts on behalf of the treasury side of government that this is a “permanent loss”.

The concept of a “loss” is inapplicable to a currency-issuing unit within government.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a helicopter drop is equivalent to an increase in the fiscal deficit in the sense that new financial assets are created and the net worth of the non-government sector increases.

It occurs when the government uses its currency-issuing capacity (linking treasury spending to central bank operations) without matching its deficit spending with debt-issues to the non-government sector.

So the central bank adds some numbers to the treasury’s bank account to match its spending plans and in return may be given treasury bonds to an equivalent value.

Instead of selling debt to the private sector, the treasury simply sells it to the central bank, which then creates new funds in return.

This accounting smokescreen is, of course, unnecessary. The central bank doesn’t need the offsetting asset (government debt) given that it creates the currency ‘out of thin air’. So the swapping of public debt for account credits is just an accounting convention.

To understand the consequences of this policy choice, ask the question, what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) increased its fiscal deficit without issuing the matching $ in debt to the non-government sector?

First, governments spend in the same way irrespective of the monetary operations that might follow. There is no sense in the claim that the government gathers money from taxes or bond sales in order to spend it.

If they didn’t issue new debt to match the increase in their deficit, then like all government spending, the treasury would instruct the central bank to credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the ‘cash system’ (bank liquidity) which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to ‘hit’ a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market (where banks loan reserves to each other) do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

The alternative is that the central bank can offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with ‘financing’ government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So the monetary measure – M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) – rise as a result of the rise in the fiscal deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

So when the government matches its deficit spending with debt-issuance to the non-government sector it is really only altering the composition of the wealth portfolio of the non-government sector. It swaps bonds for bank deposits essentially.

What would happen if there were bond sales to the non-government sector? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury ‘borrowing from the central bank’ and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target.

If private debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the long-time Bank of Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

You are now in a position to realise that Michael Heise clearly misunderstands what a helicopter drop is.

He writes:

In practice, helicopter money can look a lot like quantitative easing – purchases by central banks of government securities on secondary markets to inject liquidity into the banking system.

In fact, the helicopter option is not akin to quantitative easing – that is a common misperception.

QE is a monetary operation that is nothing more than the central bank swapping bank reserves (central bank money) with bonds (or other financial assets) held by the non-government sector.

It was introduced on the false premise that banks were not lending because they had insufficient reserves. Cure? Boost their reserves. How? Use central bank money which is in inexhaustible supply to buy bonds held by the banks in return for reserves. QED! Right?

Wrong! Even the mainstream economists must surely be catching on by now that banks do no need reserves to lend. They worry about reserves after the fact and know they can always get them from the central bank anyway, who operates to prevent financial instability, which might include large scale defaults within the payments system (that is, cheques bouncing because banks didn’t have the reserves to back the loans they had issued).

The only way QE could boost economic activity was because it reduced longer interest rates (because it increased the demand for longer-term bonds and drove down their yields). However, this mechanism also didn’t work because the state of sentiment has been so poor that households and firms have been reluctant to borrow no matter how cheap the loans might have become.

The helicopter option is a fiscal intervention which injects new net financial assets into the non-government sector and directly stimulates aggregate spending.

There is a world of difference between the two actions.

Further, whether governments issue debt to the non-government sector or not, there is no difference in the inflation risk of the deficit spending.

Michael Heise falls into the mainstream trap by assuming increases in bank reserves are inflationary.

He links a helicopter drop to Milton Friedman and then tries to invoke the standard Monetarist line with respect to inflation:

As Milton Friedman often said, in economics, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

In historical terms, Milton Friedman introduced the terminology of a ‘helicopter drop’ into the literature. The association is flawed.

In his 1948 article by Milton Friedman wrote (p.5):

… government expenditures would be financed entirely by tax revenues or the creation of money, that is, the use of non-interest bearing securities. Government would not issue interest bearing securities to the public.

[Reference: Friedman, M. (1948) ‘A Monetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability’, American Economic Review, 38, June, 245-64.]

But while it might give progressives strength to argue for what is essentially Overt Monetary Financing (OMF) because even the arch free market economist supported the approach, the reality is somewhat different.

Friedman’s proposals were part of what was known as the Chicago Plan (emanating out of the free market bastion at the University of Chicago), which proposed a broad regime change where private banks would be prevented from creating new money and public deficits would be the only source of new money.

Equally, the government would run a balanced fiscal position over the cycle and destroy the money created in the downturn when they ran offsetting surpluses in the upturn.

This is a very different proposition to the MMT (and other) suggestions for OMF to become part of a bringing together of monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate economic activity.

Michael Heise thinks that OMF (helicopter money) would be inflationary:

In fact, there are major downsides to helicopter money. Most important, by enabling the monetization of unlimited amounts of government debt, the policy would undermine the credibility of the authorities’ targets for price stability and a stable financial system. This is not a risk, but a certainty, as historical experience with war finance – including, incidentally, in Japan – demonstrates only too clearly.

He is referring to the intervention in Japan by its “Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo” in the early 1930s as a means of heading off the Great Depression.

I discussed that in detail in this blog – Takahashi Korekiyo was before Keynes and saved Japan from the Great Depression.

Michael Heise claims that the stimulus from Takahashi Korekiyo’s helicopter drop generated “a powerful wave of inflation”.

But his historical recall is poor.

There were three notable sources of stimulus introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo:

1. The exchange rate was devalued by 60 per cent against the US dollar and 44 per cent against the British pound after Japan came off the Gold Standard in December 1931. The devaluation occurred between December 1931 and November 1932. The Bank of Japan then stabilised the parity after April 1933.

2. He introduced an enlarged fiscal stimulus. In March 1932, Takahashi suggested a policy where the Bank of Japan would underwrite the government bonds (that is, credit relevant bank accounts to facilitate government spending).

This proposal was passed by the Diet on June 18, 1932. The Diet passed the government’s fiscal policy strategy for the next 12 months with a rising fiscal deficit 100 per cent funded by credit from the Bank of Japan.

Bank of Japan historian Masato Shizume wrote in his Bank of Japan Review article (May 2009) – The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Ipact of the World Depression – that:

Japan recorded much larger fiscal deficits than the other countries throughout Takahashi’s term as Finance Minister in the 1930s.

On November 25, 1932, the Bank of Japan started ‘underwriting’ the government’s spending.

3. The Bank of Japan eased interest rates several times in 1932 (March, June and August) and again in early 1933. This easing followed the cuts by the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank in the US. Monetary policy cuts were thus common to each but the size of the fiscal policy stimulus was unique to Japan.

[Reference: Shizume, Masato (2009) “The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Impact of the World Depression”, Bank of Japan Review, 2009-E-2]]

What followed is clear:

1. Real GDP growth returned quickly and stood out by comparison with the rest of the world which was mired in recession. Between 1932 and 1936, real industrial production grew by a staggering 62 per cent.

2. Employment, which had also plummeted in the early days of the Great Depression, grew robustly after the Takahashi intervention.

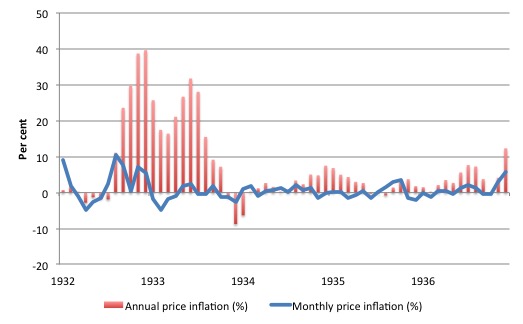

3. Inflation spiked as a result of the exchange rate depreciation in 1933 but quickly fell to low and relatively stable levels in 1934 as the economy’s growth rate picked up under the support of the fiscal and monetary stimulus.

It was clear that abandoning the Gold Standard was a crucial first step because it gave the government space to introduce major domestic stimulus policies. These policies were not possible under the Gold Standard because they would have pushed out the external deficit and the nation would have lost its gold stocks.

The following graph uses price data from the Bank of Japan to show the annual and monthly inflation between January 1932 and December 1936 in Japan.

The fiscal stimulus continued well beyond inflation spike, which was largely due to the exchange rate depreciation engineered by the Bank of Japan.

To claim that the OMF policy adopted by the Japanese government led to “a powerful wave of inflation” is false.

Michael Heise also falsely imputes causality when he says that:

Korekiyo’s subsequent attempts to rein in public deficits by slashing military spending failed. The military rebelled, and Korekiyo was assassinated in 1936.

However, a close reading of history will tell you that his monetary acumen or otherwise had anything to do with his assassination (in his sleep by gunshot and sword) by rebel army officers in 1936 during the so-called – February 26 Incident – which was a failed coup d’état.

He had in fact reduced military funding because he was a moderate and wished to reduce Japan’s martial tendencies. Enemies were thus made and they were the type of enemies that carried weapons and knew how to use them!

Michael Heise also reprises the Weimar scare story.

Hyperinflation examples such as 1920s Germany and modern-day Zimbabwe do not support the claim that fiscal deficits cause inflation.

In both cases, there were major reductions in the supply capacity of the economy prior to the inflation episode.

Those examples provided very little guidance on what would happen to a modern state which abandoned matching fiscal deficits with debt issuance to the non-government sector as noted above.

There is a dishonesty in journalism that keeps throwing those examples up without informing the reader of what actually happened in each case.

Please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.

But we soon get to the nub of the story – which reveals the incongruity of his argument.

He says that it would be politically difficult to rein in government spending under OMF:

The truth is that the central bank would struggle to defend its independence once the taboo of monetary financing of government debt was violated. Policymakers would pressure it to continue serving up growth for free, particularly in the run-up to elections …

The problem, which Friedman identified in 1969, is that while helicopter money generates more demand in an economy, it does not create more supply. So the continued provision of helicopter money after an economy has returned to normal capacity utilization – the point at which demand and supply are in equilibrium – will cause inflation to take off.

So there you see the concern in a nutshell.

First, he believes we cannot trust our elected representatives. So it is better to constrain them with voluntary rules and straitjackets, which then create mass unemployment and low growth.

I find that argument ridiculous. The ballot box constrains politicians. And progressives have to also work hard to improve governance and oversight.

Second, you see that he is confusing the monetary and fiscal operations (spending with no debt issuance) with the inflation risk inherent in spending.

No-one who advocates OMF is suggesting that a government would continue expanding nominal spending via ever-growing deficits once an economy had reached full capacity and full employment. It is obvious that if such a strategy was pursued then ever-increasing inflation would be the result.

This is because firms cannot squeeze any more real output out of the resources in use.

Alternatively, when there are idle resources (such as unemployed labour and machines), an expansion of nominal spending will likely be mostly absorbed by higher production (real output) and firms will be highly reluctant to try to increase prices for fear of losing market share to other firms in the sector.

Most importantly, growth in nominal spending can continue even when the economy is operating at full capacity as long as it matches the growth in that productive capacity and doesn’t strain the capacity of the economy to respond to the extra spending with output growth.

So it is false to claim that ‘helicopter money’ (OMF) after full employment is reached becomes inflationary. It does not if the supply side expands in proportion.

Once you understand that it is the spending growth that carries the inflation risk rather than the monetary operations that might accompany that growth, you realise that commentators like Micheal Weise really do not grasp the essentials of the monetary system they claim expertise over.

He conflates the monetary gymnastics with the spending and thinks it is the former that is the inflation risk.

As noted above, the inflation risk is not reduced if governments sell debt to match the increase in their deficit or not.

A simple way of thinking about it is that the cash to buy the bonds issued by the government was not being spent anyway. The bond sale just offers the non-government sector a chance to swap a non-interest bearing financial asset for an interest-bearing asset (a swap within the saving or wealth portfolio).

The US government can buy as much of its own debt as it chooses

Here is an update on some research I did in this regard a few years ago which appeared in these blogs – The nearly infinite capacity of the US government to spend – When the government owes itself $US1.6 trillion – and more recently (September 2013) – The US government can buy as much of its own debt as it chooses

There are a few data sets that you can pull together to break the total US public debt outstanding into various categories. The US Treasury Department provides an extensive data resource – search for Ownership of Federal Securities. The US Treasury also provide data which provides a Foreign breakdown.

The US Federal Reserve provides Consolidated Balance Sheet data.

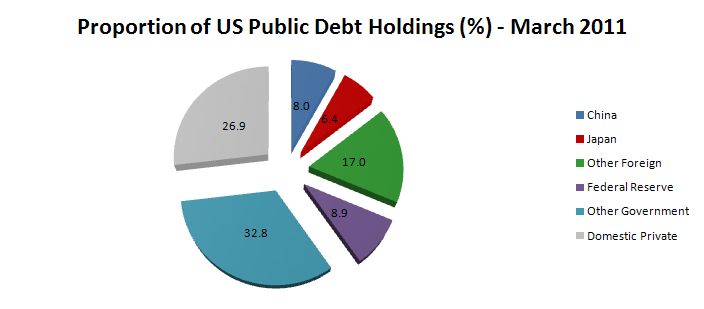

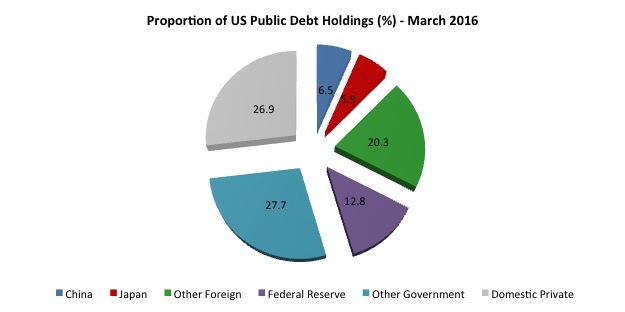

The following pie-chart shows the proportions of total US Public Debt held by various “interesting” categories as at March 2011. This chart tells you that the government sector held about 42 per cent of its own debt in March 2011. These holdings were either in the intergovernmental agencies or the US Federal Reserve.

The Chinese holdings were around 8 per cent of the total and hardly consistent with the rhetoric of the deficit terrorists that China was bailing the US government out.

The three largest foreign US debt holders at March 2011 were China (8 per cent); Japan (6.4 per cent) and Britain (2.3 per cent). The total foreign held share was equal to 31.4 per cent in March 2011.

The US Federal Reserve held 8.9 per cent of total US public debt in March 2011 – that is, more than China. The total holdings were around $US 1,274,274 million.

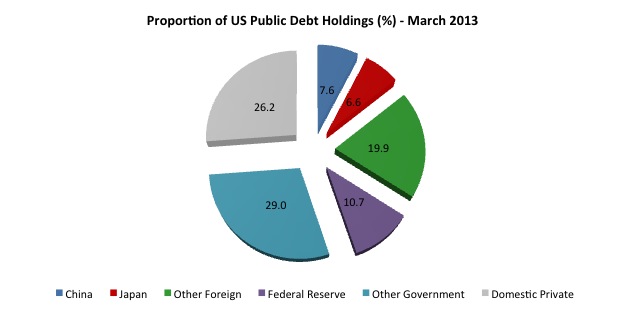

The following pie-chart represents the situation in March 2013, two years later. This chart tells you that the government sector held about 39 per cent of its own debt in the March-quarter 2013 and the private sector held the rest.

The Chinese holdings had fallen to 7.6 per cent which has been about constant since the end of 2011.

The three largest foreign US debt holders at March 2013 are China (7.6 per cent); Japan (6.6 per cent) and the so-called Caribbean Banking Centers, which include Bahamas, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Netherlands Antilles and Panama (1.7 per cent). The Oil Exporters come next (1.6 per cent). The Oil Exporters include (Ecuador, Venezuela, Indonesia, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Gabon, Libya, and Nigeria).

The impact of the British austerity is noticeable. In March 2011, Britain was the third largest holder of US public debt (at 2.3 per cent of total US public debt). By March 2013, this had dropped to 0.95 per cent. They shed $US166 billion worth of US treasury securities in that 24 month period).

The total foreign held share of outstanding US public debt was equal to 34.1 per cent in March 2013 – which is a relatively stable proportion.

The following pie-chart represents the situation in March 2016, three years later. This chart tells you that the government sector held about 39 per cent of its own debt in the March-quarter 2013 and the private sector held the rest.

The Chinese holdings had fallen further to 6.5 per cent in the three years to the March-quarter 2016. The two largest foreign US debt holders at March 2016 were China (6.7 per cent) and Japan (5.9 per cent).

The data no longer allows an easy breakdown for the Caribbean Banking Centers (Bahamas, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Netherlands Antilles and Panama), which had been the third largest and the Oil Exporters (Ecuador, Venezuela, Indonesia, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Gabon, Libya, and Nigeria) who had previously been number four.

The total foreign held share of outstanding US public debt was equal to 32.7 per cent in March 2016 – which is a relatively stable proportion but slightly down on the proportions found in 2013.

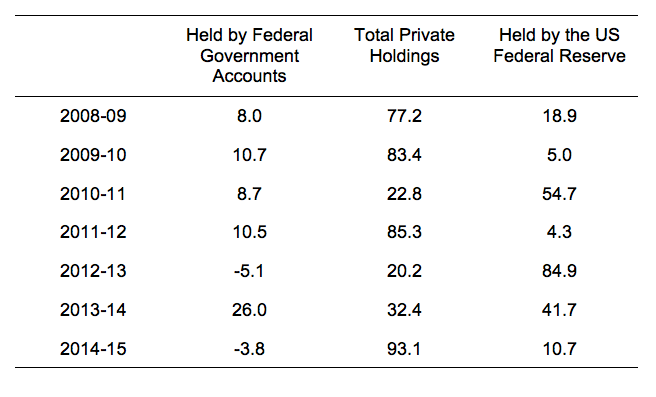

The following Table shows the proportions of the total change in US federal government debt for the calendar years 2009 (so the change is between 2008-09 and so on) to 2014-15 (up to December 2015) accounted for by the main holders – Federal Government Accounts, Total non-government (private), which is, in turn, decomposed further into US Federal Reserve holdings. There are other components not included.

In 2011, the increases in the US Federal Reserve’s holdings accounted for 54.7 per cent of the total increase in US federal government debt. That fell away to 4.3 per cent in 2012 and then rose again to 84.9 per cent in 2014. In 2015, the proportion was 10.7 per cent.

There was a dramatic shift in the mix of debt holders other than Federal Government accounts in 201 and 2013. The central bank can alter this proportion whenever they choose and that includes to purchase any debt that the private sector chooses not to purchase.

Proportions of the total change in US federal government debt (% of total change)

In other words, the US government (consolidated Treasury and central bank) can always assume the role as its own largest lender. That is, the Government can always borrowing from itself!

That is how nonsensical these voluntary conventions are. They sound robust but in the end the currency-issuer is the currency-issuer and can always work around the so-called constraints.

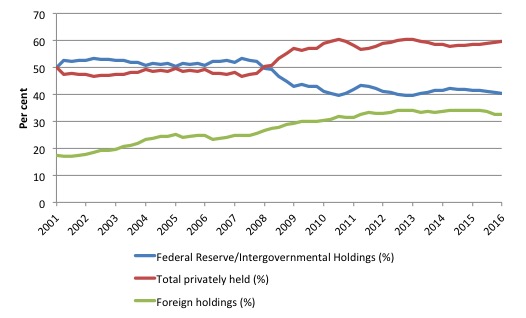

The next graph shows the evolution from March 2001 to March 2013 of the US public debt by private, public and foreign holdings (%). The foreign holdings are a subset of the private series.

There are some interesting points to note. At a time when the US public debt ratio has risen beyond what the mainstream claim is the danger point (80 per cent) – the point after which those spreadsheet mavens claim insolvency is nigh (Rogoff etc) – the private demand for US public debt has risen.

Private markets know that there is no substantive default risk involved in holding the US Treasury debt.

The other point, in relation to the rising foreign share is that you cannot conclude that the foreigners (China, Japan etc) are ‘funding’ the US government. The US government is the only government that issues US currency so it is impossible for the Chinese to ‘fund’ US government spending.

To understand the trend shown in the graph more fully we need to appreciate that the rising proportion of foreign-held US public debt is a direct result of the trade patterns between the countries involved (and cross trade positions).

For example, China will automatically accumulate US-dollar denominated claims as a result of it running a current account surplus against the US. These claims are held within the US banking system somewhere and can manifest as US-dollar deposits or interest-bearing bonds. The difference is really immaterial to US government spending and in an accounting sense just involves adjustments in the banking system.

The accumulation of these US-dollar denominated assets is the ‘reward’ that the Chinese (or other foreigners) get for shipping real goods and services to the US (principally) in exchange for less real goods and services from the US. Given real living standards are based on access to real goods and services, you can work out who is on top (from a macroeconomic perspective).

Note that a worker in Detroit or some other degenerate industrial region in the US who is suffering from unemployment as a result of cheaper imports coming from nations with lower labour standards (pay and conditions) than the US is unlikely to agree with me. In his/her case I wouldn’t agree with me either.

But from the perspective of macroeconomics there is no issue.

The point is that the US Federal Reserve Bank (as in the case of other central banks around the world) have been taking up significant proportions of the outstanding government debt in the last 10 years. In some years, this proportion has been very high.

We didn’t observe any major inflationary spikes associated with these shifts in monetary operations underpinning the government debt-issuance (and deficit) outcomes.

Please read my blog – Direct central bank purchases of government debt – for more discussion on this point.

Also please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Conclusion

Mainstream economists just cannot get out of their rut when it comes to understanding OMF and its impacts.

Until they fully appreciate that helicopter money is a fiscal intervention rather than a monetary intervention (such as QE) they will keep writing ridiculous Op Ed pieces.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill (referring to Friedman’s 1948 paper) says “Equally, the government would run a balanced fiscal position over the cycle and destroy the money created in the downturn when they ran offsetting surpluses in the upturn.”

That’s a correct interpretation of that paper far as I can see. But didn’t Friedman argue later in his career that government should effect the same small annual increase in the money supply?

Weimar and Zimbabwe not only suffered from a loss in productive capacity but were also creating currency to pay off large foreign currency debts (treaty of versaille was reparations and IMF USD loans) which created and reinforced huge exchange rate depreciation which led to runaway inflation.

I have to take issue with this statement:

“when there are idle resources (such as unemployed labour and machines), an expansion of nominal spending will likely be mostly absorbed by higher production (real output) and firms will be highly reluctant to try to increase prices for fear of losing market share to other firms in the sector.”

That may be the result initially, but shortly thereafter most likely nearly all businesses will inflate their prices…because as Minsky correctly observed “the fundamental direction of capitalism is up” and who and what is to stop them from doing so?

Now this is certainly not an argument for the idiocy of austerity and the further rule of the business model of Finance over every other business model and 95% of the general population. What it is, is an argument for is the intelligent policy of a reciprocally gifted (first to the consumer and then back to the merchant) discount substantially higher than any rate of inflation at the point of retail sale which would be

1) irresistible to every enterprise,

2) would not be intrusively stupid because the discount would not be implemented until AFTER the enterprise’s best competitive price was discovered at the terminal end of the entire productive process which is point of retail sale,

3) democratically increase aggregate demand

4) be price deflationary and yet fit seamlessly within profit making systems

5) severely reduce the dependence of both enterprise and the individual on the Banking and Financial systems whose utterly idiotic monopoly on credit creation, claim to ownership of that credit despite the fact that they create it out of nothing and whose 5000 year old problematic status is way over due for terminal correct.

Jake,

“…were also creating currency to pay off large foreign currency debts…”

The problem there was not that money was being created to pay those debts. It would not matter where the money came from to pay them – they might have issued debt and probably did. The problem was simply the conversion to foreign currencies IMO.

Kind Regards

or let the target rate fall to zero (the long-time Bank of Japan solution). Bill Mitchell

It sounds absurd that interest rates in fiat would ever fall to zero but if they do so is it not because the general population may not use fiat except in the form of unsafe, inconvenient physical fiat, a.k.a. currency, but is instead forced to work through a government privileged usury cartel of depository institutions who alone may have accounts at the central bank?

May I humbly suggest that the root of our problems with the banks is their special privileges?

Andrew Anderson,

MMT says that the natural short term interest rate is zero percent.

In my view, the only reason why central banks have an interest rate above zero is so that they can attempt to influence inflation by, in turn, attempting to control the provision of credit.

In reality this is a vain attempt, because central banks can barely control the provision of credit, let alone inflation -that role should naturally fall to fiscal policy.

Kind Regards

“From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a helicopter drop is equivalent to an increase in the fiscal deficit in the sense that new financial assets are created and the net worth of the non-government sector increases”

Given Bill’s strictness in applying the necessity modality to statements from the mainstream, I do feel uncomfortable it his continual association of the word deficit with increasing expenditure. If I correctly understand the MMT view, raising government spending in absolute terms does not necessitate an increase in the deficit. It does not even necessitate an increase in spending as percentage of GDP. It seems just as likely to have the opposite effects if the increased spending is correctly judged to maximise growth and spending multipliers.

Given the negatives associated with the word deficit and the irrelevance of the quantity from a policy perspective, why continue to use it?

“who and what is to stop them from doing so?”

Competition.

IF a firm raises prices, then it will lose out in competition to a firm that pushes volume and maintains prices.

So if prices go up, then you have a monopoly or oligopoly in your economic system and should address that via the usual state competition authority responses – break up large firms or capitalise a competitor.

“Given the negatives associated with the word deficit”

Given the negatives associated with the word spending why continue to use it? It’s what the government chooses to buy and what it chooses to stop the population buying that matters.

Well there’s the competition for market share and then there’s the impulse to profit….which every enterprise has, and within the latter more basic impulse you will find that an enterprise seeing another enterprise raising its prices will tend to match it, not via collusion, but because in an environment of perceived high level of demand it’s a doable thing with little or no market loss consequences.

If, however, you had a retail discount of sufficient percentage, say 40% and up, all of which was rebated back to participating merchants, it would render petty and creeping inflation impossible, make it more visible to consumers and likely discourage it altogether despite the increase in purchasing power because profits from volume of sales would rise.

And, if an enterprise was a serial inflater of its prices without real cost accounting cause, gracious and yet hard and fast consequences like taxation and/or loss of discount privileges in addition to loss of market share could be regulatory policy options.

Mainstream economics is a faith Japans long term government sector deficit levels ,QE levels

and inflation levels have not stopped assertions that QE is inflationary so if reality cannot dent the faith

largely untried OMF is bound to be considered as inflationary.If you start by believing the invisible hand

sets the right price then anything that upsets the price mechanism is inflationary.If however you understand

inflation by conflict models and price as costs plus mark up dependent on competition then no such

inevitability exists .

Firms will try to maintain profit levels if wages rise by rising prices dependent on existing mark up and

competition.

Here in the UK there is insufficient competition in the rental sector and of course there are real land limits.

General increased spending without rent controls are likely to see rents rise even more.

“That may be the result initially, but shortly thereafter most likely nearly all businesses will inflate their prices…because as Minsky correctly observed “the fundamental direction of capitalism is up” and who and what is to stop them from doing so?”

we have 35 years of down, and falling global inflation, and we may be about to enter a period of widespread deflation, unless some bright spark decides to turn one of our current small wars into a large one 😉

MMT says that the natural short term interest rate is zero percent. CharlesJ

Who can know what the natural short term interest rate in fiat is since only depository institutions may use it*?

So I suggest that MMT advocates broaden their outlook to consider a world without government privileges for banks – especially since the banks are a recurrent threat to peace and prosperity.

*except for unsafe, inconvenient physical fiat, notes and coins which the general population may still use to some extent.

Not that non-low interest rates are good but how those are brought is very important – unless we think systematically looting the poor and other less and non so-called creditworthy for the benefit of the banks and the most so-called credit worthy, the rich, is inconsequential.

It is correct that helicopter money is not INHERENTLY inflationary. The economy as a whole however IS inherently cost inflationary by the cost accounting convention that all costs must go into price. This may be galling to those who are hung up in general equilibrium theory, “hard money” beliefs and even left leaning economists like Steve Keen whose “emergent qualities” are actually just the failure to observe and account the moment to moment rate of flow of total individual incomes in ratio to total costs accurately. And if the system IS inherently cost inflationary in this manner, then injecting money into it in any way that doesn’t immediately reverse this ratio (classical notions of equilibrium are just another orthodoxy to overcome) and make it “the higher disequilibrium” that sets both the individual and the system free and rectifies the long standing unethical dominance of the business model of Finance….misses the mark.

Andrew,

FYI Bill has previously advocated a fully nationalised banking system. Perhaps that covers your concerns. I think that regulating banks to within an inch of their lives might be good enough. As for the “short term interest rate” I referred to, I am talking about the rate at which banks lend to each other.

Kind Regards

As for the “short term interest rate” I referred to, I am talking about the rate at which banks lend to each other. CharlesJ

Of course. My point is that interest rates in fiat are unjustly suppressed in that only banks in the private sector may deal with fiat in the form of convenient, inherently risk-free accounts at the central bank. Why can’t we all do so?

So basically the banks are glutted with fiat “reserves” while the population may not even use fiat except in the form of unsafe, inconvenient physical fiat, aka “currency.”

Regulate or nationalize? Are those our only choices? Why not DE-PRIVILEGE the banks? Think that might reduce problem? Hmmm?

Andrew,

“Why not DE-PRIVILEGE the banks? Think that might reduce problem? Hmmm?”

You can do that by nationalising them or heavily regulating them. Nationalising them, for example, removes any profit motive and allows governments to force them to pass on all privileges to their customers.

Kind Regards

Nationalising them, for example, removes any profit motive and allows governments to force them to pass on all privileges to their customers. CharlesJ

It’s not just the banks who unjustly benefit but also the more so-called credit worthy at the expense of the less and non so-called credit worthy.

So what will determine so-called credit worthiness if the banks are naturalized?

1) Wealth? As is the current situation?

and/or

2) Politics?

The problem is that government privileges for the banks allow one segment of the population, the wealthy and/or politically connected, to legally steal from the rest of the population.

The ONLY solution is to de-privilege the banks – leaving them 100% private with 100% voluntary depositors.

But you’ll say that free banking has been tried and failed? But not so since citizens, their businesses, etc. have NEVER to any significant extent been allowed accounts at the central bank itself. Instead, the horrible mistake of government-provided deposit insurance and other privileges for depository institutions was instituted.

get rid of banks altogether.

why create a interest burden on the economy and on the people, and besides the central bank has timing mismatch issues with trying to have any effect on credit growth, and are unable to forecast pricing with any degree of confidence, given recent history, and given the prediliction of bankers to run their balance sheets like casinos, it all ends in tears periodically, leading to financial instability, depressions and wars.

we are 98% chimpanzee, with all the bad habits , and banks and nuclear weapons should be big no no’s .

banks will be an artefact of history within the next 200 years.

“Who can know what the natural short term interest rate in fiat is since only depository institutions may use it”

firstly , in a highly inelastic market without government intervention through a support price , you would have a zero price at zero bid.

but yes, the central bank makes its best guess at where it thinks the price ought to be, and usually gets it wrong when you look at the data, so they certainly don’t know what the price should be at any given moment 😉 the magic number appears to 1.5 at the moment.

the support rate pegs the yield on the rest of the maturity structure , so it is highly relevant to all of us, not just depository institutions.

I deal with trying balance yield and volume for my job on a daily basis, and I can tell you now, if you don’t have reliable market data that tells you what the volume might be, you can forget about working out what the yield should be.

central bankers curse, reacting defensively to movements in volume generated by the banks, and that’s why they haven’t got a snowballs chance in hell of getting the price right. so why take risk. let it fall to zero.

“and within the latter more basic impulse you will find that an enterprise seeing another enterprise raising its prices will tend to match it,”

They won’t in a sufficiently competitive market. If that happens, then you have a problem with competition and need more of it in that market segment. So at that point you start breaking up firms, and introducing competitors *including government funded ones*. And most importantly you let market participants know that is what the government will do if it sees price rises and that the government expects to see quantity responses to increased demand, not price responses.

Then you will get a quantity response to maintaining profits, not a price response.

Yes, well that’s the orthodox explanation/justification. But orthodoxy as we see is not always accurate. But let’s suppose what you say is correct. What do we do about:

1) the almost complete dominance of the economy and nearly everyone in it by Finance

2) the fact that the cost accounting convention that all costs must go into price which means that the additional costs of depreciation and waste as a flow as well as the increasingly disruptive forces of innovation and AI on aggregate demand are making modern capital intensive economies price inflationary

“Yes, well that’s the orthodox explanation/justification.”

No, that’s how businesses actually work internally when you work in them. Prices aren’t set by accountants. They are set by businessmen based upon what they can get for their product pretty much regardless of the costs. There is no guarantee that the markup you want for your product is what you are going to get and it is the job of the government to contain capitalism in a competitive environment that keeps that uncertainty going – largely by ensuring that those who raise their prices have a tendency to go to the wall.

“No, that’s how businesses actually work internally when you work in them. Prices aren’t set by accountants.”

Precisely….and devastatingly for both the system and the individual that the businessmen are so unaware of the economic and monetary significance of cost accountings’ conventions…..and accountants aren’t mathematically trained to do calculus with the datums they work with constantly. If it weren’t so tragic, it would be hilarious.

What you say is undeniably how business decisions actually are made, and there is undoubtedly legitimate temporal reasons for that, but if there is an underlying and ever present inherent cost factor still de-stabilizing the system….then the analysis is incomplete. Integrate truths and relevancies. That is the process of Wisdom whether it be personal or economic and monetary.

get rid of banks altogether. mahaish

De-privileging* the banks would leave them with deposits that were, by definition, at-risk, not necessarily liquid investments, not co-mingled with necessary liquidity as is the case today.

“The issue which has swept down the centuries, and which will have to be fought sooner or later, is the people versus the banks. “-John Acton (1834-1902)

*We have a one-time opportunity with the proper abolition of government provided deposit insurance to reverse a lot of relative wealth inequality since new reserves should be needed for the transfer of at least some currently insured deposits to inherently risk-free individual citizen, business, etc. accounts at the central bank itself. Those new reserves should be equally distributed in step with the progressive abolition of deposit insurance to all adult citizens.

“Prices aren’t set by accountants. They are set by businessmen based upon what they can get for their product pretty much regardless of the costs”

indeed neil,

marginal cost pricing is relevant, even though its part of the orthodoxy. when you go for yield and when you go for cash flow is a tricky business in competitive markets with transparent pricing.

and because of googlenomics, most markets are more competitive rather than less competitive these days, with some glaring exceptions offcourse, one being google themselves 😉

depending on market conditions, and the price sensitivities involved, even if prices are rising, gap pricing to get volume effects so you can meet your targets is highly relevant. so a competitor might actually drop prices, or let them rise more slowly than there competitors in a rising market in order to steal market share.

the nature of market competition determines the level of convexivity of the yield curve, or even if you run a inverse yield curve, assuming managers know what their doing.

this is how you would run a truly proactive business, but a lot of busineses arent all that proactive, and they are left scratching their heads as to how they have been robbed by their competitors 😉

@Neil and Mahaish

You’ll note that the problem I’m referring to is a systemic/macro-economic inherent state of a continual scarcity ratio of total individual incomes to total costs that drives and necessitates the build up of debt in order to palliate but not resolve that scarcity ratio,…..not the micro-economic decisions and policies of individual enterprises.

First, thanks again to Bill for going where nobody else seems to be going here – the actual postulation of the social-economic benefits to ‘publicly-issued’ exchange media.

There seems little appreciation for Bill’s correct explanation of the errors of the PS piece, notably regarding that there would never be any need for an offsetting ‘chit’ to be held by the CB, or anyone, ever, when that institution (being not really part of the government) makes the payments for government spending as ordered by the Treasury.

What it seems is lacking is in this discussion is, from where does Treasury obtain its authority to make such an order.

Authority to issue any nation’s money is notably inherent within monetary sovereignty, but the free exercise of that sovereignty is limited by laws that transfer that money-issuing authority to other, private, autonomous operations, such as the FRBS in the U.S.. Also notable is the fact that this FRBS – FRBNY “acts as” the central-bank-US (thus ‘consolidated’) but is a completely private Bank-corporate institution. As are the private FOMC Members, all of whose salaries are paid from the private earnings of the Cartel. Not a public nickel spent there, except as to reduce the repayment of interest TO the government.

At any rate, the more widely advanced the discussion of public money becomes – no matter what the term du jour – the better off we will all be , and the sooner.

[Bill deleted link to a report on PM]

Thanks again, Doctor Bill .