The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The ‘fiscal space’ charade – IMF becomes Moody’s advertising agency

The IMF has taken to advertising for the ratings agency Moody’s. It is a good pair really. Moody’s is a disgraced ratings agency and the IMF has blood on its hands for its role in less developed nations and for its incompetence in estimating the impacts of austerity in Europe. Neither has produced research or policy proposals that can be said to advance the well-being of nations. Moody’s has shown a proclivity to deceptive behaviour in pursuit of its own advancement (private largesse). The IMF struts around the world bullying nations and partnering with other institutions to wreak havoc on the prosperity of citizens. Its role in the Troika is demonstrative. Anyway, they are now back in the fiscal space game – announcing that various nations have no alternative but to impose harsh austerity because the private bond markets will no longer fund them. They include Japan in that category. Their models would have drawn the same conclusion about Japan two decades ago. It is amazing that any national government continues to fund the IMF. It should be disbanded.

As background to this blog, please read my blogs:

1. Ratings firm plays the sucker card … again

3. Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies

4. Ratings agencies and higher interest rates

5. Moodys and Japan – rating agency declares itself irrelevant – again

The IMF define – Fiscal Space – to be the :

… room in a government´s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy. The idea is that fiscal space must exist or be created if extra resources are to be made available for worthwhile government spending. A government can create fiscal space by raising taxes, securing outside grants, cutting lower priority expenditure, borrowing resources (from citizens or foreign lenders), or borrowing from the banking system (and thereby expanding the money supply). But it must do this without compromising macroeconomic stability and fiscal sustainability – making sure that it has the capacity in the short term and the longer term to finance its desired expenditure programs as well as to service its debt.

It is always good to work with first principles as they will rarely lead you astray. They cut out all the humbug in the media, the statements by politicians and the ideological ravings of vested interests.

The above definition is not based on first principles but is an ideological statement. It assumes that the government in question has the same constraints that restricted governments during the gold standard when currencies were convertible and exchange rates were fixed.

Here are the relevant first principles, which many of you will know well by now.

In a fiat monetary system:

- A sovereign government is not revenue-constrained which means that fiscal space cannot be defined in financial terms.

- The capacity of the sovereign government to mobilise resources depends only on the real resources available to the nation.

- A currency-issuing government can always meet the liabilities it issues in its own currency.

- Nations that have ceded their sovereignty by entering currency zones (such as the Eurozone); by dollarising their currencies; by running currency boards; and similar arrangements clearly are not sovereign and face the same constraints that a country suffered during the gold standard era.

On September 1, 2010, the IMF released Staff Position Note SPN/10/11 – Fiscal Space. It contained some econometric modelling that sought to define how much scope there was for governments to expand their deficits.

It is a very dodgy piece of analysis (more later).

On December 20, 2011, the credit rating agency Moody’s released a special report – Fiscal Space. This paper informs Moody’s – fiscal space tracker, which purports to present a “fundamentals-based measure of the risk of sovereign debt default”.

The analytical framework used by Moody’s comes directly from the 2010 IMF paper. The credit rating agency just mimics the approach outlined in that 2010 Staff Position Note.

I do not recommend reading either paper. I have done the due diligence for you and I conclude that you are better to watch the grass grow or count socks in your drawer. Something like that.

This week (June 2015), the IMF released a new Staff Discussion Note (SDN/15/10) – When Should Public Debt Be Reduced? – which essentially attempts to repeat the same spurious arguments and methodology presented in the 2010 paper ((some of the authors of the 2010 paper overlap here).

In this new attempt, the IMF is now taken to advertising the work of Moody’s, which was just an application of its own work.

But they clearly thought that the fancy looking, multi-coloured graphic that Moody’s presented is worth repeating as a pedagogical device to ram homethe message.

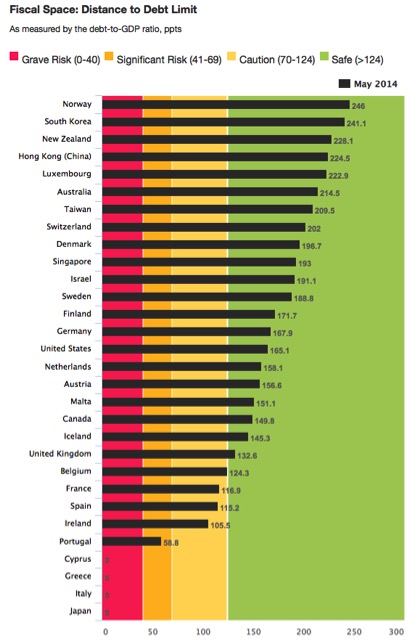

Here is the graph (Figure 1 in the 2015 IMF paper). The graph has 30 nations which are classified as having either grave risk, significant risk, caution or safe in terms of an alleged “distance to debt limit”.

So it is bright enough! But not very smart.

Let’s apply those first principles. Here are the 30 nations with some extra relevant information.

Australia – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt.

Canada – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt (only for central bank reserve management).

Iceland – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

Israel – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

Japan – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt.

New Zealand – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt

Norway – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt.

South Korea – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

Sweden – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

Taiwan – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

UK – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt.

USA – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no or negligible foreign currency debt.

Singapore – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, no foreign currency debt.

Switzerland – sovereign issuer, freely convertible currency, some foreign currency debt.

Denmark – sovereign issuer, loose peg to euro, some foreign currency debt.

Hong Kong (China) – sovereign issuer, pegged to USD

Austria – non sovereign in currency.

Belgium – non sovereign in currency.

Cyprus – non sovereign in currency.

Finland – non sovereign in currency.

France – non sovereign in currency.

Germany – non sovereign in currency.

Greece – non sovereign in currency.

Ireland – non sovereign in currency.

Italy – non sovereign in currency.

Luxembourg – non sovereign in currency.

Malta – non sovereign in currency.

Netherlands – non sovereign in currency.

Portugal – non sovereign in currency.

Spain – non sovereign in currency.

So those sovereign-issuing nations with no or negligible debt denominated in foreign currency have no default risk on their public debt associated with factors such as size of deficit, outstanding debt stocks etc. Their government’s can always meet their liabilities and would only default as an insane act of politics.

There are no financial risks associated with their debt.

I haven’t done a complete analysis of the proportions of debt that are denominated in foreign currency for the other currency-issuing nations. My feeling is (from old data) that the proportion varies but is small.

At any rate, these nations can always meet their domestic obligations (including servicing debt denominated in their own currency which is held by foreigners) but in some weird situation might find it hard to service their foreign-denominated debt. Highly unlikely but there is a smidgen of risk.

For the non-sovereign in currency nations – all of which are ‘happily’ ensconced in the failed Eurozone, they all face public debt default risk. The risk varies but they all are exposed to it.

So the first thing we conclude from this vacuous study by the IMF, which Moody’s thinks is useful for their purposes too (that should be warning in itself that something is not robust), is that it is a meaningless exercise to combine truly sovereign nations with no default risk with another block of nations, all of which face default risk.

The IMF concept of fiscal space is outlined more fully in the 2010 paper I cited above. Basically, they conduct a very contentious econometric exercise where they estimate the “debt limit” of each nation.

How do they do that?

They relate the primary fiscal balance (difference between government spending and revenue net of interest payments) to the outstanding public debt in what they term a “primary balance reaction function”.

This tells them what governments do with respect to fiscal policy at different debt levels.

They claim when debt is low, the primary balance is relatively unresponsive but as the debt levels rise, the primary balance “responds more vigorously but eventually the adjustment effort peters out as it becomes increasingly more difficult to raise taxes or cut primary expenditures further.”

So there is allegedly some debt level where the:

… primary balance does not keep pace with the higher effective interest payments (equal to the interest rate-output growth rate differential multiplied by the debt ratio), there will be a debt level above which the dynamics become explosive, with the public-debt-to-GDP ratio rising without bound. At that point, the government must either undertake extraordinary fiscal adjustment (i.e., primary adjustment beyond the country’s historical response to rising debt) or default on its debt. It is natural to consider this point the debt limit-and the distance to it from the current debt ratio to be the available fiscal space.

Effectively, they claim that the debt limit is when the private bond markets stop ‘funding’ the government and radical austerity is required.

They relate that reaction function with an “effective interest rate schedule”, which tells the government the rate at which interest payable exceeds the real growth rate of the economy multiplied by the outstanding debt. It is a growth-adjusted interest payments relationship. The technicalities need not concern us.

Essentially, the debt limit is reached when the debt and interest payments are so high that:

… there is no sequence of positive shocks to the primary balance (in the absence of an extraordinary fiscal effort) that would be sufficient to offset the rising interest payments. Therefore, debt becomes unsustainable, and the interest rate effectively becomes infinite.

Close down government time!

They put the numbers in the graph (above) to these concepts by econometric modelling. Essentially they run regressions which include explanatory variables such as:

Debt

Output gap

Trade openness

Inflation

Oil prices

Dependency ratio

Political stability

etc

The results should be treated with a grain of salt. I only list a few issues – there are many statistical issues that one could raise but in the interests of keeping this blog readable I will demur.

First, they do not differentiate between currency-issuers (as above) and the Eurozone nations (currency-users).

Second, they use technical dodges (ad hoc autoregressive corrections) to mop up estimation problems. These usually indicate a mis-specified econometric relationship and means that the model is incorrect.

Third, they admit that “the coefficients on the debt ratio, however, are common across countries; this is necessary because (as hypothesized) the response of the primary balance varies by the debt level, but the full range of debt is not observed for any individual country.”

That point is in a small print footnote to the results Table 1. What does it mean. It means they have not been able to freely estimate the most important unknowns in their model (the relationship between the primary balance and debt) and so they have just imposed the relationship on all nations.

In econometrics, this is called imposing a restriction on the model to simplify the estimation process. The problem is that such impositions should be stochastically ‘tested’ using significance tests. One examines the difference between the restricted model and the unrestricted model and uses special tests to determine whether these differences are statistically significant or not. If not, the imposition of the restriction is acceptable and simplifies the estimation process.

They did not do that. So the coefficients on the debt variables are essentially ‘made up’ and cannot be applied with confidence to all the nations (especially those with no relevant data).

Fourth, conceptually, the model ignores basic realities. The central bank of a sovereign nation can set whatever yield on public debt that it considers desirable. These nations might pretend they at the behest of the private bond markets but when push comes to shove, the central bank always dominates.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

So the idea that a government has to stop net spending or needs harsh austerity if the private bond markets start pushing up yields to ridiculous levels is ridiculous.

Even the ECB in the Eurozone has demonstrated it can control yields whenever it wants by buying up government bonds in secondary markets.

Fifth, a sovereign, currency-issuing nation does not even have to issue debt to maintain deficit spending levels at whatever level they desire. It can instruct the central bank to credit bank accounts at will. Given the propensity of such governments to impose voluntary restrictions on themselves, such a move might require a legislative change.

But the fact is that when the crisis hit these governments had no trouble getting cash.

Sixth, the case of Japan. The IMF/Moody’s modelling would have declared Japan to have zero fiscal space nearly two decades ago. This has been a repeated claim.

Since that time, Japan has continued to run large deficits and issue bonds and very low yields. It reached the IMF debt limit from their models years ago.

So how do they explain that?

In this blog – Moodys and Japan – rating agency declares itself irrelevant – again – I discussed earlier attempts by Moody’s to impose this moronic framework on Japan in 2011.

Even earlier, the same pantomime was played out in the 1990s. Japan is an advanced nation with currency sovereignty. In November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s Investors Service began the first of a series of downgradings of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa rating away.

The next major Moody’s downgrade occurred on September 8, 2000.

Then, in December 2001, Moody’s further downgraded the Japan Governments yen-denominated bond rating to Aa3 from Aa2. On May 31, 2002, Moody’s Investors Service cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

The then Japanese Finance Minister responded (with some foresight):

They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.

Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors.

In the New York Times (July 6, 2002) the logic of the rating decision was questioned:

How … could a country that receives foreign aid from Japan have a better rating than Japan itself? Japan, with an economy almost 1,000 times the size of Botswana’s, has the world’s largest foreign reserves, $446 billion; the world’s largest domestic savings, $11.4 trillion; and about $1 trillion in overseas investments. And 95 percent of the debt is held by Japanese people …

Former Moody’s President, John Bohn Jr. had in 1995 claimed that: “We’re in the integrity business: People pay us to be objective, to be independent and to forcefully tell it like it is.” (Reference: Ratings Trouble, Institutional Investor, October 1995: 245).

Integrity business history lesson

In January 2011, the – US Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission – which had been formed by the US government to “examine the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States”, issued its final – Report.

Among the key conclusions were the following:

1. The “financial crisis was avoidable” – it was the “result of human action and inaction … The captains of finance and the public stewards of our financial system ignored warnings and failed to question, understand, and manage evolving risks within a system essential to the well-being of the American public.”

2. “there were warning signs. The tragedy was that they were ignored or discounted.”

3. “The prime example is the Federal Reserve’s pivotal failure to stem the flow of toxic mortgages, which it could have done by setting prudent mortgage-lending standards. The Federal Reserve was the one entity empowered to do so and it did not.”

4. “We conclude widespread failures in financial regulation and supervision proved devastating to the stability of the nation’s financial markets … the financial industry itself played a key role in weakening regulatory constraints on institutions, markets, and products. It did not surprise the Commission that an industry of such wealth and power would exert pressure on policy makers and regulators. From 1999 to 2008, the financial sector expended $2.7 billion in reported federal lobbying expenses; individuals and political action committees in the sector made more than $1 billion in campaign contributions.”

5. “We conclude dramatic failures of corporate governance and risk management at many systemically important financial institutions were a key cause of this crisis … Too many of these institu- tions acted recklessly … Our examination revealed stunning instances of governance breakdowns and irresponsibility”.

6. “We conclude a combination of excessive borrowing, risky investments,and lack of transparency put the financial system on a collision course with crisis … leverage was often hidden – in derivatives positions, in off-balance-sheet entities, and through ‘window dressing’ of financial reports available to the investing public.”

7. “We conclude there was a systemic breakdown in accountability and ethics”.

And in the context of today’s blog:

8. “”We conclude the failures of credit-rating agencies were essential cogs in the wheel of financial destruction:

The three credit rating agencies were key enablers of the financial meltdown. The mortgage-related securities at the heart of the crisis could not have been marketed and sold without their seal of approval. Investors re- lied on them, often blindly. In some cases, they were obligated to use them, or regulatory capital standards were hinged on them. This crisis could not have happened without the rating agencies. Their ratings helped the market soar and their downgrades through 2007 and 2008 wreaked havoc across markets and firms.

The Commission used Moody’s as a case study. They said that the agency “rated 45,000 mortgage-related securities as triple-A. This compares with six private-sector com- panies in the United States that carried this coveted rating in early 2010”.

They found that “83% of the mortgage securities rated triple-A” by Moody’s in 2006 “ultimately were downgraded”.

The financial firms paid the ratings agencies to get these triple-A endorsements, while the ignorant public considered the ratings to be ‘independently’ derived from sound modelling. Nothing of the sort occurred.

Earlier, on April 23, 2010, the US Congress Permanent Committee on Investigations commenced a hearing – Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: The Role of Credit Rating Agencies.

After deliberations and evidence, the Committee, which has used Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s as “case studies” reported that “those credit rating agencies allowed Wall Street to impact their analysis, their independence, and their reputation for reliability. And they did it for the money”.

They found that the rating agencies “were operating with an inherent conflict of interest, because the revenues they pocketed came from the companies whose securities they rated … like one of the parties in court paying the judge’s salary”.

Further, the Committee found that the ratings agencies gave top ratings to financial products that they knew would not be “unlikely to perform”. For some products, up to 97% that had been given triple-A ratings were downgraded to junk status.

The Committee found the “credit rating models” were built on wrong assumptions, which was admitted by Moody’s and S&P.

Evidence showed the S&P operatives knew that there had been “rampant appraisal and underwriting fraud in the industry for quite some time” but the credit rating agencies “failed to adjust their ratings to take … [this criminality] … into account”.

A tawdry story no doubt.

Conclusion

It is amazing to see the IMF and Moody’s playing tag with each other and peddling the myths together. One is a disgraced ratings agency and the other had blood on its hands for its role in less developed nations earlier and more recently for its incompetence in estimating the impacts of austerity in Europe.

A good match I guess. Both should be disregarded.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Quite agree. The concept “fiscal space” is the biggest load of nonsense that’s appeared since the word “nonsense” was invented.

Strange name too. Its called “Back to Basics Fiscal Space” as if this is a 101 subject at a university. Implying this is a building block from which whole swathes of economic though must be extended and constructed.

Then defines the most erronous set of criteria.

When these agencies/IMF talk about fiscal unsustainability I can’t seem to find WHERE it defines HOW these cataclysmic unsustainable debt limits actually come into effect on the physical currency users. How?

Perhaps all the bond purchasing entrepreneurs simultaneously stop mid sentence, half way through their sandwich or coffee one day. Immediately pack up their bags, declare they are not ever going to use the countries currency, any of its services or infrastructure and leer jet it out of there. Followed by other ‘rational’ citizens having near infinite future expectations and clarity having seen their bond purchasing bretheren refuse the currency, they themselves follow suite immediately exiting the country.

This would make a great novel to be placed in the ‘fiction’ category spoecial thanks to IMF and moody’s for the imaginative basis for such a novel.

How come Singapore is not monetarily sovereign?

Seems odd since it has its own dollar.

Dear John Doyle (at 2015/06/04 at 20:27)

It was a typo. I had included it twice and cut and paste in haste given I was running late today.

best wishes

bill

I agree with Ralph.

Surely the main consideration as regards government debt is not debt/GDP ( comparing a stock to a flow) but the finance costs of that debt as a percentage of government expenditure.

But Bill, something that puzzles me as I head into 300 level Macro soon is this: what is the difference, in practical terms, between a govt borrowing overseas to fund expenditure or simply getting the CB to print the money.

And let’s assume that the govt is responsible i.e. Regard for inflation and corruption free.

‘Investors re- lied on them’…. from point 8 above.

Freudian slip- or nor – it made me smile.

Great post, as ever!

@Luc Hansen

what is the difference, in practical terms, between a govt borrowing overseas to fund expenditure or simply getting the CB to print the money”

Borrowing money (overseas or not) provides a risk free interest bearing financial asset to whomever buys the bonds. Since bond buyers are generally banks/insurance companies, this can be seen as corporate welfare.

“Printing” money (or more likely: crediting an account electronically) does not provide any interest to anybody. Actually, the “printing” action, as you call it, can be conflated with the act of spending, since nothing (apart from self-imposed rules and/or laws) prevents the government to just order the central bank to credit whatever account it desires, as payment for good and services purchased by the government.

Luc,

You suggest the “finance costs” should determine how big national debt is allowed to grow. I sort of agree, but I’ll try to be more precise, and as follows.

As MMTers keep pointing out, the state must meet the private sector’s “savings desires”: i.e. the state must issue base money and/or debt. That objective could be met by having base money only and no debt (as advocated by Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler).

Alternatively I can think of arguments for some debt, but paying only a low rate of interest: preferably less than inflation. The advantage of “less than inflation” that is that the state pays a negative REAL rate of interest: i.e. the state profits at the expense of its creditors.

As to whether the state should borrow to fund infrastructure projects, I can make up my mind on that one. So that’s a fat lot of help for you….:-)

As to borrowing from overseas, doing so improves a country’s balance of payments which gives a temporary boost to its living standards. I don’t see any good excuse for doing that on a large scale, which is an additional reason for holding interest on the debt down, as suggested above. I.e. if a country pays a lowish rate on its debt, foreigners won’t buy too much of its debt.

“Followed by other ‘rational’ citizens having near infinite future expectations and clarity having seen their bond purchasing bretheren refuse the currency, they themselves follow suite immediately exiting the country.”

Taxes create demand for the currency. And fees and fines and licenses e.g. immigration fee inposable.

“As to whether the state should borrow to fund infrastructure projects, I can make up my mind on that one. So that’s a fat lot of help for you….:-)”

Ralph, infrastructure leads to increase in land values that is unearned. So I think this is how it should be “funded.”

My two-cents from this side of the pond…..

President Obama/Council of Economic Advisers:

Virtually every pundit, and every concerned person for that matter, agree that our number one problem facing America, today, is the lack of JOBS….

So why are we having so much trouble solving this problem?

And why do we not have more introspection into our asking that question?

If we had the solution, we wouldn’t have the problem-so for starters we need to drill down on our methodology for job creation.

And here we have two opposing mind-sets…..with WW II, and the [FULL] EMLOYMENT ACT OF 1946, as the watershed moment setting us on two distinctly different paths leading into our 21st Century economy.

One path believes that “anybody wanting to work should be able to find a job”–and 86% of Americans believe this should be the case….

The path we have actually taken, however, holds that “the market can provide anybody wanting a job, with a job”–which would be ideal if it were true-

The research, however, shows that it is unworkable-and only ONCE since WW II has this path resulted in an unemployment [hereafter UE] rate below 3%–in 1953-leaving millions jobless in its wake….

It is unworkable, even ignoring the adverse consequences of UE, because if the market fails, the jobless are out of luck-and it has resulted in 60% minority UE in our inner cities, turning them into war zones, with drug economies and an epidemic of homicides.

In short, we have been unable to solve our UE problem because our two choices have been one path that is unworkable, and the other unused….

But what if we took a third path, a blend of the two?

Dr. William F. Mitchell, a world renowned economist, has proposed such a solution in THE BUFFER STOCK EMPLOYMENT MODEL: An expanding and contracting public workforce, that expands during downturns in the market and contracts as employee return to the private sector.

And we have the “legal authorization”, on the books [15 U.S. Code § 3101 ], to trigger this model anytime our UE rate in America rises above “3%”. That is, at no time should our UE rate in America exceed 3% [see also HR 1000].

Further, this is a Pro-Market solution-the market thrives when we have a robust, employed, consuming workforce…

A “win-win”…the American people win, and the market wins….

Ref: FULL EMPLOYMENT IS A PRO-MARKET CONCEPT, Amazon

Jim Green, Democrat opponent to Lamar Smith, Congress, 2000

Jim, Good post. The reason why it does not happen is twofold:

1) Common voters in the U.S don’t understand how the monetary system works, and how it can be used to make sure idle real labor resources are put to work

2) New program proposals come attached to tax increases which make the proposal not very marketable. #1 ties into marketability too with the common refrain “How are we going to pay for it?”

We need Greece to walk away from the Euro.

Then for MMT specialists to advise the country. I don’t know why we are not in constant touch with countries like Russia and South American countries ?

Japan has showed the Neoliberals for decades what can be achieved. We need more countries to be a poster boy so we can debunk the myths on a huge scale.

Only problem is the political elite and the familys who have effectively run these countries will do everything in their power to stop that progress.

Greece would be a great step because it borders the EU. Once the myths are exposed other countries will follow.

MMT need a lobby group that lobbies countries that have fallen out with the Neoliberals.

It is very hard for many people to look beyond their own experiences as a household.

Issuing bonds to account for the gap between government spending and tax returns

does not help the perception problem.What would be the potential problems of a

government leaving international (BIS) agreements?

Is their a role for some open money transfers as investment for public works or

income supplements?Even using QE more openly as an accounting cooperation may be

the least worse option in the current conditions ?A commitment for central banks to

immediately buy back half of bond issues would neutralize the servicing of loan worries as

interest payments would then be fiscally neutral for governments.

Matt McOsker….Thx for considering my post….your key phrase for me is “How are we going to pay for it?”. I know Bill supports deficit spending but that is a very touchy subject in America, at $17 trillion-and I suspect at first glance it is seen as another massive government program-but I don’t see it that way. For instance HR 1000 is deficit-neutral, and would be paid for by a tiny fraction on all stock transactions. My preference, which I call The Neighbor-To-Neighbor Job Creation Act, is a federally mandated Social Insurance, owned by our employed, to provide a fund to hire/train our unemployed. The job creation in either case, would be a grant-in-aid type to local jurisdictions-preferably with a focus on infrastructure repair. In any case I think the job creation must contain these elements:

1] It is based on the truism that we have far more work that needs to be done in America, than we have persons to fill these jobs….the notion that these are make work jobs is nonsensical….

2] Renewable funding is mandatory….this is not a “jump-start” solution until the market kicks in [the methodology driving our policies in America, today]-and preferably based on the BUFFER STOCK EMPLOYMENT MODEL-an expanding and contracting public workforce-that expands during a downturn in the market, and contracts as employees return to the private sector.

3] The funding is deficit-neutral [for the reason cited above-and politically it would never get off the ground otherwise, in America-and for the reason you cited the “Common voter”.

How I read this document is different. It is obviously full of usual invocations of pagan gods and references to alchemy and astrology. It has to be. But the main message is that it’s time to back-pedal on austerity in at least some countries. It is enough. Save it for better time.

This is what I have found in the document:

bs statement 1

bs statement 2

…

bs statement k

“It turns out that the optimal policy involves living with the debt forever, so the new path of debt

is essentially “parallel” to the baseline path.”

bs statement k+1

…

bs statement n

The era of austerity commenced in 2009 after the G-20 summit in London. We are approaching a G-7 summit. The austerity could have run its course and it might be quietly shelved for a while – not because it is less a “brilliant” intellectual concept as in 2009 but because more important global conflicts between the West and Ruso-China have emerged or rather reached a new more aggravated phase. Just look at how the agenda of Tony Abbott’s government has changed – they have quietly accepted rising public debt (because they have no choice).

v good point Adam k.Austerity may be just for ‘leftish’ governments.

But it is hard to get the genie back in the bottle .Very difficult in the eurozone.

Of course the real waste is we have a real historic opportunity certainly here in the uk.

Has there ever been a larger non damaging in inflationary terms fiscal space?

High unemployment and underemployment.Low productivity growth,GDP growth,Inflation

and Interest rates.

The increasing quick buck model of modern capitalism is starving investment in the most

important things for most people.To deliver decent standards for all we desperately need

to improve the amount and particularly the quality of the things the drive for maximizing

short term profits fails to provide for the majority.Housing,Education,Healthcare and Transportation.

For the future add Research and the production of Energy which does not emit CO 2.

By the way I am not a socialist just a strong advocate of a mixed economy.Today here in the uk

and I suspect all over the OECD nations the need for a massive program of public works

in these six key areas is glaring and the fiscal space enormous.To put it into MMT terms

the saving desires of the vast majority remained unfulfilled.

If it makes anyone feel better Russia and China are setting up alternatives to the IMF and World Bank … the BRICS bank, and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank. They are just getting started but could offer a real alternative to the IMF and World Bank. In tandem with that they are also beginning programs to free international trade from dependence on the US dollar, starting with their own trade. Unfortunately a lot of ‘neoliberal’ thought infests Russia and even China to some extent (see Russia ‘cutting back’ to deal with problems related to sanctions, but there seems to be more hope there for more rational policies than there are in the US or Europe.