It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Ratings firm plays the sucker card … again

Companies that sell shonky products under false pretenses are typically prosecuted by the authorities. Those that sell shonky products generally are typically run out of business. But there is one class of such products that seem to escape the scrutiny of both the authorities and the market. Indeed, they seem to have bluffed many governments into believing that shonky is good. Last week, the patently irrelevant Moody’s rating agency downgraded Britain’s sovereign debt ratings from Aaa to Aa1. The fact it was headline news indicates how stupid we all are. The fact that George Osborne then had to lie about what it meant showed how stupid he is. The fact that the Opposition leader described it as a humiliating blow showed how stupid (and opportunistic) he is. How a company that was complicit in the financial crisis can command so much free advertising is beyond me. I must be stupid! The fact is that the latest ratings are without meaning or import.

The ABC (our national broadcaster) has a program Business Today and it featured the ratings downgrade. The first segment was a cross to a so-called expert in Sydney holding a tablet to look important with her private bank’s logo occupying about half the screen in the background. The ABC has a strict non-advertising policy. Since when does one of the big four banks get free advertising on our national broadcaster

It wasn’t as if the analysis was worth listening to. We got gems like the Moody’s decision was “Well priced in” and that she was “Not expecting a market reaction today on the market”, which I thought was about the most intelligent statement among the 2 minutes of platitudes. Really, play school is better than that trash that goes as informed reporting.

The segment that followed featured George Osborne saying that the downgrading confirmed everything he has been saying – too much debt. He lied.

The press release (February 22, 2013) – Moody’s downgrades UK’s government bond rating to Aa1 from Aaa; outlook is now stable – outlines the “key interrelated drivers” of the decision to downgrade:

1. The continuing weakness in the UK’s medium-term growth outlook, with a period of sluggish growth which Moody’s now expects will extend into the second half of the decade;

2. The challenges that subdued medium-term growth prospects pose to the government’s fiscal consolidation programme, which will now extend well into the next parliament;

3. And, as a consequence of the UK’s high and rising debt burden, a deterioration in the shock-absorption capacity of the government’s balance sheet, which is unlikely to reverse before 2016.

If someone out there who knows anything can tell us how any of these “drivers” can alter the following realities then please come forth:

1. Britain issues its own currency.

2. Britain has total control of its own fiscal and monetary policy.

3. Britain floats its currency.

4. Britain has never voluntarily refused to honour its liabilities under these arrangements.

I am sure there is someone out there who wasted their cash and bought the book by Reinhart and Rogoff about sovereign debt defaults. Even on the remainder desk, the book is not worth the money. At any rate they will claim Britain defaulted in 1932, which is near enough in history to be worried about.

The reponse is that Britain did not satisfy conditions 1-3 as above.

But at any rate, the “default” was an invitation only to bond holders to take a lower interest rate and extend the maturity date on the 5 per cent War Loan Bonds, which were issued in 1917 to “pay” for the prosecution of the First World War effort.

At the time (June 30, 1932), the British Prime Minister (Neville Chamberlain) told the – British Parliament – that:

Talk of conversion, has been in the air a long time, and naturally so, for it has been growing increasingly obvious that the War Loan at 5 per cent was out of relation to the yield of other Government securities, and, moreover, that the maintenance of that old War-time rate attaching to so vast a body of stock and hanging like a cloud over the capital market was a source of depression and a hindrance to the expansion of trade …

After a long period of depression we have recovered our freedom in monetary matters. We have balanced our Budget in the face of the most formidable difficulties, and we have shown the strongest resistance of any country to the general troubles affecting world trade. I am convinced that the country is in the mood for great enterprises, and is both able and determined to carry them through to a successful conclusion …

It is my confident hope that the great mass of the holders will respond to this invitation …

For the response we must trust, and I am certain we shall not trust in vain, to the good sense and patriotism of the 3,000,000 holders to whom we shall appeal.

The reference to regaining its “monetary freedom” was the decision to abandon the Gold Standard (temporarily) in September 1931, after the Bank of England lost nearly all of its foreign currency reserves trying to defend the Pound, which depreciated sharply after the decision.

However, despite struggling through the 1920s, the British government held onto the budget surplus mantra, which Chamberlain’s government was still holding out as a virtue in the midst of the Great Depression. So even though they abandoned convertibility they really didn’t understand what “monetary freedom”, as the currency issuer, required in the face of major non-government spending collapse.

In other words, even if the terms of the bodn issue at the time were nonsensical, the 5 per cent yields was in no way a “source of depression” nor a “hindrance of trade”.

The source of depression in the UK at the time was the fiscal drag arising from the obsession with budget balance and the weakness of private spending. The “Treasury View” exacerbated the problem by trying to solve the rising unemployment with money wage cuts.

In fact, the income flow from the bonds were supporting growth and the conversion offer had the effect of stifling growth because 90 odd per cent of the bond holders, which included households as well as large institutional investors agreed to the offer.

The other obvious point to note is that the so-called “default” was not any such thing. It was a voluntary offer which could have been rejected. The Government did not propose to coerce investors and force non-payment. It just said “be nice Brits and believe our lies and give up some of your income entitlements”. Most did but that is not the point.

But in the modern day, the sovereign debt ratings are about “credit risk”, which means the investor faces a risk of not being paid the amount they expect at the time they contract for.

One of the big four ratings agencies offer the following – definition:

Credit ratings are forward-looking opinions about credit risk. Standard & Poor’s credit ratings express the agency’s opinion about the ability and willingness of an issuer, such as a corporation or state or city government, to meet its financial obligations in full and on time

That definition is representative.

The conclusion is that in the case of a private firm, the ratings may have some relevance, given that such debt carries a risk. Whether the corrupt ratings agencies are the appropriate vehicle to provide the “markets” which such intelligence is another matter.

But in the case of sovereign debt (by which I mean a government satisfying the terms above 1-3, plus not issuing any debt obligations in a foreign currency) the ratings are irrelevant. Why we think otherwise is a mystery that can only be explained as falling into the same class of transactions as the shonky salesperson trying to sell new immigrants the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

In other words, fraud.

The same company also offers a document – Sovereign Government Rating Methodology

And Assumptions – outlining in general terms what sovereign debt ratings are all about.

The opening salvo says that the document:

… provides additional clarity by introducing a finer calibration of the five major rating factors that form the foundation of a sovereign analysis and by articulating how these factors combine to derive a sovereign’s issuer credit ratings …

Clarity and articulation are about education. Education is about knowledge.

While the documents very authoritative it doesn’t take long to find that it presents a confused conflation of different monetary systems, exchange rate arrangements and pure conservative ideology – which means it should be disregarded as mis-informed hype rather than insightful analysis.

Paragraph 11 gives the game away:

A sovereign local-currency rating is determined by applying zero to two notches of uplift from the foreign-currency rating following our methodology outlined in subpart VI.D. Sovereign local-currency ratings can be higher than sovereign foreign-currency ratings because local-currency creditworthiness may be supported by the unique powers that sovereigns possess within their own borders, including issuance of the local currency and regulatory control of the domestic financial system. When a sovereign is a member of a monetary union, and thus cedes monetary and exchange-rate policy to a common central bank, or when it uses the currency of another sovereign, the local-currency rating is equal to the foreign-currency rating.

That should be enough to tell anyone that those “unique powers” preclude credit risk unless there are extraordinary political factors, which would predispose a government to default voluntarily. Which would suggest that the ratings agencies were staffed by political scientists rather than economists who rave on about deficits and growth.

You will read on to find out the “overall calibration of the sovereign ratings criteria is based on our analysis of the history of sovereign defaults” and they use various data sources including Reinhart and Rogoff. They consider the data to be continuous from the “beginning of the 19th century”.

A lot of commentators have seized on the recent book by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff entitled This Time is Different as an authority on the question of sovereign default. It might be an historical documentation of sovereign debt events. But trying to link these events and presenting them as a meaningful guide to the present day is where the problem lies.

Here is draft version of This Time is Different that you can read for free.

Of critical importance, quite apart from the other issues that one might have with Reinhart and Rogoff’s analysis (and I have many), one has to appreciate what they are talking about. Most of the commentators do not spell out the definitions of a sovereign default used in the book. In this way they deliberately (or through ignorance – one or the other) blur the terminology and start claiming or leaving the reader to assume that the analysis applies to all governments everywhere.

It does not. On Page 2 of the draft, Reinhart and Rogoff say:

We begin by discussing sovereign default on external debt (i.e., a government default on its own external debt or private sector debts that were publicly guaranteed.)

How clear is that? They are talking about problems that national governments face when they borrow in a foreign currency. So when so-called experts claim that their analysis applies to the “entire developed world” you realise immediately that they are in deception mode or just don’t get it … full stop.

Many advanced nation have no foreign currency-denominated debt. They might have domestic debt owned by foreigners – but that is not remotely like debt that is issued in a foreign currency. Reinhart and Rogoff are only talking about debt that is issued in a foreign jurisdiction typically in that foreign nation’s currency.

It turns out that many developing nations do have such debt courtesy of the multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank who have made it their job to load poor nations up with debt that is always poised to explode on them. Then they lend them some more.

But it is very clear that there is never a solvency issue on domestic debt whether it is held by foreigners or domestic investors.

Reinhart and Rogoff also pull out examples of sovereign defaults way back in history without any recognition that what happens in a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates is not commensurate to previous monetary arrangements (gold standards, fixed exchange rates etc). Argentina in 2001 is also not a good example because they surrendered their currency sovereignty courtesy of the US exchange rate peg (currency board).

Further, Reinhart and Rogoff (on page 14 of the draft) qualify their analysis:

Table 1 flags which countries in our sample may be considered default virgins, at least in the narrow sense that they have never failed to meet their debt repayment or rescheduled. One conspicuous grouping of countries includes the high-income Anglophone nations, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. (The mother country, England, defaulted in earlier eras as we shall see.) Also included are all of the Scandinavian countries, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark. Also in Europe, there is Belgium. In Asia, there is Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Korea. Admittedly, the latter two countries, especially, managed to avoid default only through massive International Monetary Fund loan packages during the last 1990s debt crisis and otherwise suffered much of the same trauma as a typical defaulting country.

We have seen the circumstances of Britain’s 1932 “default”. Britain has never defaulted when its monetary system was based on a non-convertible currency.

A large number of defaults are associated with wars or insurrections where new regimes refuse to honour the debts of the previous rulers. These are hardly financial motives. Japan defaulted during WW2 by refusing to repay debts to its enemies – a wise move one would have thought and hardly counts as a financial default.

But if you consider the “virgin” list – how much of the World’s GDP does this group of nations represent? Answer: a huge proportion, especially if you include Japan and a host of other European nations that have not defaulted in modern times.

Further, how many nations with non-convertible currencies and flexible exchange rates have ever defaulted? Answer: hardly any and the defaults were either political or because they were given poor advice (for example Russia in 1998).

Reinhart and Rogoff don’t make this distinction – in fact a search of the draft text reveals no “hits” at all for the search string “fixed exchange rates” or “flexible exchange rates” or “convertible” or “non-convertible”, yet from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective these are crucial differences in understanding the operations of and the constraints on the monetary system.

Further, if you consider the Latin American crises in the 1980s, as a modern example, you cannot help implicate the IMF and fixed exchange rates in that crisis. The IMF pushed Mexico and other nations to hold parities against the US dollar yet permit creditors to exit the country. For Mexican creditors this meant that interest returns skyrocketed (the interest rate rises were to protect the currency) and the poor Mexicans wore the damage.

It was clear during this crisis that the IMF and the US Federal Reserve were more interested in saving the first-world banks who were exposed than caring about the local citizens who were scorched by harsh austerity programs. Same old, same old.

What about the detail provided by Moody’s?

In their press release explaining the decision, they introduce several concepts of “risk” without really telling readers that they are not talking about sovereign credit risk.

We read about “interest rate risk” – which relates to movements in bond prices. We read aout “risk exposure” in the context of a further European slowdown impacting on the real GDP growth rate in Britain. That has nothing to do with the capacity of the British government to honour its liabilities.

But the “main driver” in their decision:

… is the increasing clarity that, despite considerable structural economic strengths, the UK’s economic growth will remain sluggish over the next few years due to the anticipated slow growth of the global economy and the drag on the UK economy from the ongoing domestic public- and private-sector deleveraging process ….

The sluggish growth environment in turn poses an increasing challenge to the government’s fiscal consolidation efforts, which represents the second driver … the rating agency cited concerns over the increased uncertainty regarding the pace of fiscal consolidation due to materially weaker growth prospects, which contributed to higher than previously expected projections for the deficit, and consequently also an expected rise in the debt burden …

More specifically, projected tax revenue increases have been difficult to achieve in the UK due to the challenging economic environment. As a result, the weaker economic outturn has substantially slowed the anticipated pace of deficit and debt-to-GDP reduction, and is likely to continue to do so over the medium term …

Taken together, the slower-than-expected recovery, the higher debt load and the policy uncertainties combine to form the third driver of today’s rating action — namely, the erosion of the shock-absorption capacity of the UK’s balance sheet. Moody’s believes that the mounting debt levels in a low-growth environment have impaired the sovereign’s ability to contain and quickly reverse the impact of adverse economic or financial shocks.

So pursuing fiscal consolidation causes the economy to tank (given slow private growth) which reduces tax revenue and means that the fiscal consolidation fails which is bad.

The circularity of the reasoning is mind-boggling. They support the fiscal austerity but also think slow growth is bad. Why? Not because it creates unemployment and rising poverty etc. But because it gets in the way of the financial goals it thinks are important.

First, they claim the currency issuing government has to reduce its budget deficit (engage in fiscal consolidation) because somehow a rising deficit is bad and erodes “the shock-absorption capacity of the UK’s balance sheet”.

Even that last statement is false and confusing. The balance sheet is a record of stocks whereas the deficit is a record of flows. A currency-issuing government can increase its spending and change tax rates any time it chooses.

There is no path-dependency of its capacity to do that. Running a surplus last period, provides the government with no extra capacity in this period to meet a spending gap opened up by an unexpected shift in non-government spending.

Running a deficit last period, provides the government with no less capacity in this period to meet a spending gap opened up by an unexpected shift in non-government spending.

In fact, we know that most times governments attempt to run surpluses (when the external account is not booming) a downturn soon follows as a result of the combination of the fiscal drag and the reliance on private credit expansion for growth.

These rating agencies seem to think that h means nothing at all. What fiscal space are we talking about? Earlier they admitted that the “risk of a fiscal financing crisis to be negligible”. That is, there is as much financial space for deficit spending as is required in the UK – as there is for any currency-issuing government.

There is near infinite financial space, which is the concept of “fiscal space” that they are referring to. There isn’t infinite real space – that is, the availability of real goods and services that can be purchased at any time with government spending.

But whatever is available for sale in UK Pounds – including all the unemployed and underemployed workers – can be purchased at any time by the national government. There is never an intrinsic financial constraint on that capacity.

Once again, we encounter lots of arbitrary (voluntary) constraints. When people say to me that the government has run out of money I just look at them (quickly recall which currency is being discussed) and say: What the Australian Government has run out of dollars?

The fact is that the British government can absorb any “adverse economic shock” at any time without exception. It might choose, as it is now, not to do so. But then the public debate would turn to examining why it was deliberately allowing unemployment to increase when it has all the means at its disposal not to have that happen.

Second, they acknowledge that the “the ongoing domestic public- and private-sector deleveraging process” is dragging down growth. Which means that their first demand – fiscal austerity – is creating the conditions that they think require a downgrade. You cannot win with that sort of logic. A is bad and has to alter but that causes B which is also bad and has to alter which would cause A to be worse which …. mindless logic.

Third, they note that the slow growth has made “projected tax revenue increases have been difficult to achieve” which is pushing up the deficit and debt ratio. Which any person with a modicum of understanding would realise was the obvious thing that would happen.

Why they thought that there would not be a increased deficit once the fiscal consolidation undermined growth is another matter that bears on their basic macroeconomic understanding in the first place. Like the IMF and the OECD, these agencies demand fiscal cuts, yet pretend that they will be offset by private sector spending growth. Even the most basic understanding of psychology tells us that confidence does not increase when sales are falling, jobs are being cut and unemployment is rising.

Fourth, in light of the weakening economy and the fact that the Government will not meet its deficit and debt reduction targets within the time frame specified in recent budget statements is also somehow bad. Why is a 90 per cent general government gross debt to GDP ratio any different to 80, 85, 120, etc.

What mindless rule is being applied here?

The whole thing is mindless. To repeat, the logic appears to be: Cut deficits to keep the Aaa rating – but that would undermine growth and push up the deficit and debt – which undermines the Aaa rating.

And the politicians and everyone else goes along with this nonsense. We really are not a very bright race of people.

Please read my blogs – Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies and Ratings agencies and higher interest rates and – Moodys and Japan – rating agency declares itself irrelevant – again – for more discussion on why the ratings agencies should be ignored and … outlawed.

The commentary by Moody’s has a lot to do with whether the government lives up to its promises (it won’t). It clearly has a lot to do with the capacity of the UK economy to grow (it won’t while all expenditure sources are in austerity mode).

The important point is what has all this to do with the default risk of the British government? The answer is none.

The bond markets certainly understand that.

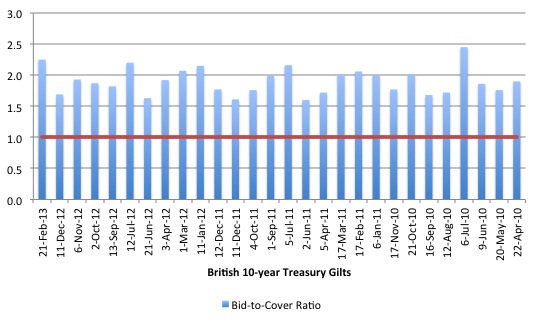

The UK Debt Management Office define the – Bid-to-cover ratio

The ratio of the total amount of bids to the amount on offer at a gilt auction or a Treasury bill tender.

The following graph using – data – from the UK DMO shows the bid-to-cover ratios for the 10-year treasury bond auctions since the current government was elected. As the recent (February 21, 2013) – Wall Street Journal article – UK Gilt Auction Attracts Very Strong Demand – noted, the ratio is a “gauge of demand”.

The data runs from left to right in time (the most recent auction being the left-most column). The red line is obviously a situation where the demand is below the funds sought (which is often referred to as an “underbought” auction).

What does this tell us? In the vernacular – the bond markets have been consistently lining up for their dose of corporate welfare.

Every auction has been oversubscribed, which is the usual state.

Conclusion

Given their propensity to corrupt behaviour (as evidenced in the various hearings that have been conducted in the fallout of the financial crisis) I would outlaw the ratings agencies immediately.

But if I was in government I would also be engaging in a large education campaign trying to inform people about how moronic the logic used by these agencies is.

This is nothing more than a game of bluff and the government has the power but pretends it doesn’t. Ridiculous.

Tomorrow I am off to Dili (Timor Leste) and will be there until early Friday of this week. I have a lot of commitments and do not know whether I will find any time to write my blog. Maybe, maybe not. But if nothing appears then you will know why. I may find it hard to get connectivity even.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Predictibly in the UK press and most of the comment, the politics is all that matters. the truth takes a back seat again. It’s rather pathetic and I’m starting to get annoyed with stupid people.

The neoliberal “meme” has it’s tentacles deeply embedded in our media, politics and educational structures as well as the general population. The truth is met with a confused and often angry retort; “everyone knows that the deficit is too high, we have run out of money, nothing can be done….what the hell do you mean the government is not ‘financially constrained’ ?”. I am not sure how it’s going to be dug out…notwithstanding excellent blogging of course!

I was at a conference over the weekend and had a discussion with a few of the participants, all educated to university level and some university teachers for many years. One of the topics discussed was where the money that the government pays for things comes from. I gave the standard MMT account. The almost universal response I got was that the situation showed that, if a fiat economy was as I had described, this showed that such a system did not work. This may have been due to my exposition or the fact that we had had a bit to drink or it was late at night, but I don’t think so. Basically, the others believed that government spending was based on taxation in one way or another. I didn’t have the conversational space to go into much detail, but it was clear that at least two of the others believed such a system to be completely unworkable and the crisis showed this to be so. The upshot of this is that we seem to have a long way to go to get the message across. I should add that although my colleagues have had social science training, none have had any training in economics. Perhaps had I been able to lay out the case in some detail, I might have been able to instill some doubt. But unfortunately … .

Larry & Neil,

MMTers (like adherents to any other set of ideas) can get too assertive, or overstate their case. And I suspect that puts potential converts off.

E.g. saying “tax and government borrowing don’t fund government spending” is too assertive. It’s better to prefix the above phrase with “strictly speaking”. And then go on to explain that if government wants to spend $X more, it will not necessarily need to collect exactly $X of tax or borrow $X. What it WILL NEED to do is to collect and amount of tax (or borrow) such that the deflationary effect of that tax/borrowing equals to stimulatory/inflationary effect of the extra government spending.

I’m reading “The nature of money” by Geoffrey Ingham. Although not always very clear in my opinion, it’s certainly a good read. Ingham acknowledges that MMT has it right operationally, but:

“Neo-chartalist seek to establish that the state does not in fact have need of its citizens’ money from taxation and bond sales in order to spend. But, as we have noted in Part 1, they appear to have missed the significance of the political nature of both origins and functions of the system. These links did not originate, for example, in the function of draining excess reserves that might exert downward pressure on interest rates. Rather, they were the historical consequence of an emerging bourgeois class’s resistance to the attempt of a powerful sovereign arbitrarily to control spending and taxation. Subsequently, the concern with the balance between spending, borrowing and taxation in, say, principles of sound money has become a matter of an implicit settlement between the state, capitalist ‘rentiers’ and the tax-paying capitalist producers and workers. Moreover, the stability of any settlement is greatly increased by its legitimization in terms of economic principles and practice. Ultimately, the political balance of these economic interests that the state is able to forge is concerned with checking its arbitrary power and establishing its creditworthiness – that is, its ability to pay its debts. This is not so much a matter of what the state is capable of in a de facto practical sense, but of how this is interpreted as legitimate or not by groups and classes (including the state itself) whose struggle for economic existence produces money. This is the actual function of sound money principles. Holders of Treasury bonds must be encouraged to believe that the state can pay interest and redeem the bonds.

The state and the market share in the production of capitalist credit-money, and, as I have stressed, it is the balance of power between these two major participants in the capitalist process that produces stable money.”

I’m not sure what to think of it. MMTers surely don’t underestimate the political side of money creation. Ingham is in fact arguing that the foundation of the BoE took place in peculiar circumstances – the struggle between the state and the bourgeoisie – 300 years ago and that you cannot just ignore those circumstances today. But then isn’t MMT part of this endless struggle?

Has anyone here read this – interesting – book?

Alex

I haven’t read it but I think the ‘Modern’ in ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ may be significant here.

Ralph, I didn’t have any opportunity of overstating the case. What I was up against was an entrenched view that took on the character of some kind of common sense status and it would have taken me more than the time I had available to me to even begin to convince them that how they saw the ‘mechanical operations’ of the economic system needed new foundations, even beginning with what might seem to a straightforward set of principles, like the relationship of taxation to government spending.

Alex,

Ingham is just plain wrong to infer MMTers miss the significance of the political origins of the system. It is implicit in so many MMT articles, the bourgeoisie rentier class are using their economic power to disproportionately influence the political system. Gaming the monetary system to further their own economic well being, whilst filling the ether with a barrage of misinformation.

The last I heard we live in a democracy supposedly with one man one vote. He offers little more to the discussion than a lame apology for the 1% to wield extraordinary political power. You can say he is simply stating the facts of the status quo. The fact also is the majority of us would prefer to live in a more egalitarian, more meritocratic society with greater economic equality.

I assume he is just leaving the gate open for the typical right wing straw man attack. The narrative is usually framed something like this……Place more power in the hands of Government (aka the people) and we will all be headed for a Stalinist gulag. The counter argument of course is…Place more power in the hands of the rentier class/ corporatocracy and we are headed for a feudalist/ facist society.

The truth is we need to prevent economic elites wielding excessive political power for their own gain (Like the robber barons) we also need to prevent entrenched Government elites abusing their power (like Stalin). The proletariat need to find a properly functioning democratic system to advance public purpose and prevent elite capture. That’s got squat all to do with Ingrams puny critique of MMT.

Ralph,

“MMTers (like adherents to any other set of ideas) can get too assertive, or overstate their case. And I suspect that puts potential converts off.”

Come on Ralph, I think you are seeing things too much from the perspective of your own personality type and belief system. if MMTers get any less assertive they might as well shut their mouths completely. There is more than one way to gain acceptance for your ideas….timidity is rarely effective.

MMT is facing a huge uphill battle on several major fronts. 1. Entrenched and antagonistic vested interests with a giant propaganda machine. 2. A right wing political consensus with very narrow framing of economic issues. 3. Institutionalised neoliberal ideology. 4. Broad public acceptance of an intuitive (but false and misleading) description of monetary operations. 5. Normal human resistance to change.

You really expect dialing back the assertiveness will further MMT…… Please…. It often takes something more than a polite nudge to make people question a deeply rooted belief.

Alex,

Please note. I have interpreted Ingham out of context. He is wrong to infer MMT lacks political perspective. However, as to his motives, you will have to read his full works to understand his bias. I don’t know his works. I just read your snapshot and fired off a few extra rounds from the hip. I am too used to dealing with the general neoliberal bias in todays society. (Pale smile)

” And then go on to explain that if government wants to spend $X more, it will not necessarily need to collect exactly $X of tax or borrow $X.”

The approach to take is neither of those.

The problem is that the individual thinks the government is constrained like they are.

The solution is to take the individual and give them the financial power of a government. Get them to imagine that they own a bank with no capital restrictions. Ask them then if it would make sense to borrow from a third party?

Get them to imagine they have a Super Platinum Credit Card with no credit limit and that can pay itself off. What would the restrictions on spending be then?

Get them to imagine that they got paid every time there was a transaction in the economy no matter where it was or who initiated it. What would that motivate them to do?

My experience trying to explain MMT usually meets with derision, followed by glimpses of understanding (after lengthy one on one discussions and debate) followed by a complete lapse of comprehension a day later when “common sense” kicks back in. This process seems to repeat endlessly 🙁

@Neil Wilson

Thanks for the suggestions, Neil. I’ll try them the next time, if I get a chance.

@Bruce

I’ve managed to convince a lady friend of mine, but she admits that there are aspects of it that she doesn’t quite understand. While my possibly faulty exposition may be the reason for this, it is true that getting this point of view across is no easy task. One person asked me why none of the financial journalists of the broadsheets ever discuss the economic system in the way that I do.

**********************************************

In the ’70s, while I didn’t develop an alternative theory, I criticized my colleagues’ neoclassical positions and the math they were using. One answer I invariably received was that I didn’t quite understand the model and that my problem could be dealt with by manipulating a few parameters. Mostly, however, the response was a kind of stonewalling. Questions involving economic history were quickly dismissed as irrelevant to contemporary concerns.

“The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd.”

– Bertrand Russell

Russell is telling us that widespread belief has no relationship with objective truth. The problem with a number of MMT ideas is that they are counterintuitive, and therefore those ideas are not widely held. Scientists and philosophers are adequately trained in handling counterintuitive ideas, but the average person in the street, and those within other pofessions, are not.

Only after Economics as a whole has emerged from the darkness and become a real science should the pronouncements of the economic mainstream be taken seriously. In the meantime their ramblings should be treated with derision.

@Andrew

Thanks for your insight. I more or less agree with you, but :

– The book is still very instructive, although I haven’t finished it yet. Ingham believes credit is endogenous and acknowledges that “neo-chartalists” are operationally right. I often cites R. Wray, by the way.

– I’ve also read “Capitalism” by the same author, which shows that Ingham isn’t neoliberal at all.

Alex,

Have you seen Ann Pettifor’s recent interesting critique of Geoffrey Ingham’s ‘Capitalism’?…

http://www.primeeconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/The-power-to-create-money-out-of-thin-air5.pdf

Ann’s not an MMT economist, but seems to have a similar point of view (she quotes Bill in her essay). I wonder if Bill agrees with Ann?

Ralph – is it overassertive or overstating a case to say that 2 + 2 =4? That statement is as true and intuitive as 2 + 2 =4. It is not a matter of emotions or framing – but of truth or falsity. To disagree with that statement is to be very confused.

Alex Hanin, Andrew, Andy, :

Wray considers Ingham’s book “The best place to start for a sociological approach to money” A Meme For Money, Part 2: The Conservative Framing. See also Ingham’s & others’ contributions to the Mitchell-Innes volume. I agree, it is a wonderful book. IMHO, the criticisms there should not be taken as a groundless attack, but observations from a somewhat different point of view than usually propounded among MMTers, and a very helpful one.

larry:if a fiat economy was as I had described, this showed that such a system did not work. One route, my preferred one is the historical / logical one, for which Ingham’s book is a fine reference: All money is “fiat” money, and always was, and always must be. Maybe it doesn’t work, but it’s been not working for many thousands of years now. 🙂