I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Friday lay day – Minimum wage in Australia creeps up

Its my Friday lay day blog but no rest for the wicked today. The Fair Work Commission, the Federal body entrusted with the task of determining Australia’s minimum wage handed down its – 2014-15 decision – on June 2, 2014. Here is my annual review of that decision plus some. The decision meant that more than 1.86 million of our lowest paid workers (out of some 11.6 million) received an extra $16.00 per week from July 1. This amounted to an increase of 2.5 per cent (down from last year’s rise of 3 per cent). The Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) is now $656.90 per week or $17.29 per hour. For the low-paid workers in the retail sector, personal care services, hospitality, cleaning services and unskilled labouring sectors there was no cause for celebration. They already earn a pittance and endure poor working conditions. The pay rise will at best maintain the current real minimum wage but denies this cohort access to the fairly robust national productivity growth that has occurred over the last two years. The decision also maintains the gap between the low paid workers and other wage and salary recipients, who themselves are suffering a major wages squeeze as corporate profits rise. The real story though is that today’s minimum wage outcome is another casualty of the fiscal austerity that the Federal Government has imposed on the nation which is destroying jobs and impacting disproportionately on low-paid workers.

The Decision

The employer groups opposed the wage rise. The Australian Chamber of Commerce said anything more than a $5.70 per week increase would be unsustainable and “dangerous”. They always say that but seem happy to advocate real wage cuts which have to undermine the sales of their members.

It is a triumph of ideology over fact.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions had sought an increase of $27 per week to ensure that the lowest paid workers participated in the productivity growth over the last year and a reversal in the rising inequality began. Their bid was also rejected in favour of an outcome that just preserves the real minimum wage when measured between June 2014 and June 2015.

In between, the inflation eroded away the real living standards of minimum wage workers.

It also failed to give the minimum wage workers any share of the increase in labour productivity, which the Fair Work Commission noted “rose by 1.6 per cent over the year to the December quarter 2014, following growth over each of the preceding three years.”

More general wage earners are also not participating in the productivity growth which is being largely pocketed by profits (capital).

In delivering the decision, the President of the FWC, Justice Iain Ross said that:

We have had particular regard to the lower growth in consumer prices and aggregate wages growth over the past year because they have a direct bearing on relative living standards and the needs of the low paid.

So as inflation falls and the rest of the workforce is squeezed out of sharing in labour productivity growth, the FWC considers the lowest paid workers should follow suit.

In parrying the complaint from employers that this would cause inflation and/or unemployment to rise, the FWC said:

Recent economic outcomes for the award-reliant industries do not suggest that the most award-reliant industries have faced a relatively difficult economic environment over the past year and provide no basis to conclude that recent minimum wage increases have significantly impacted on the economic performance of the award-reliant industries.

The minimum wage outcome is another casualty of the fiscal austerity that the Federal Government has imposed on the nation which is destroying jobs and impacting disproportionately on low-paid workers.

Minimum wage principles

I regularly write analytical reports for trade unions who are defending industrial matters on behalf of the members in the Fair Work Commission in Australia. That often requires me to appear as an expert witness in the relevant matter. I am currently working on several matters for the unions, particularly with regard to low paid workers.

There is a growing trend among employers to try their hand in the FWC to revise the legal award determinations for particular sectors and eliminate job protection, penalty rates, etc. It is a sort of spray gun approach – attack everything just in case you get something.

The claim is always the same – we cannot pay the conditions we agreed. It says more about their management skill and sense of business ethics than anything else.

Yet the FWC has repeatedly found that the wage determinations over many years across many sectors have not undermined the profitability of the firms.

However, I do not consider minimum wages should be set on private sector capacity to pay principles. The employers should adjust not the workers.

The principle that the FWC should follow is clear.

The minimum wage as a statement of how sophisticated you consider your nation to be or aspire to be. Minimum wages define the lowest material standard of wage income that you want to tolerate.

It should be a wage that allows a person (and family) to participate in society in a meaningful way and not suffer social exclusion or alienation through lack of income.

It is a statement of national aspiration.

In any country it should be the lowest wage that society considers acceptable for business to operate at. Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not have the ‘capacity to pay’ that wage, then a sophisticated society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy.

Such firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear.

This approach establishes a dynamic efficiency whereby the economy is continually pushing productivity growth forward and allowing material standards of living to rise.

I consider that no worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable material standard of living just because some low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country and make ‘cheap’ profits.

I don’t consider that the private ‘market’ is an arbiter of the values that a society should aspire to or maintain. That is where I differ significantly from my profession.

The employers always want the wages system to be totally deregulated so that the ‘market can work’ without fetters. This will apparently tell us what workers are ‘worth’.

The problem is that the so-called ‘market” in its pure conceptual form is an amoral, ahistorical construct and cannot project the societal values that bind communities and peoples to higher order considerations.

The minimum wage is a values-based concept and should not be determined by a market.

All of that is in addition to the usual disclaimers that the pure ‘competitive market, cannot exist for labour given the imbalances between workers and employers and the fact that the use value of the labour power is derived within the transaction (that is, the worker has to be forced to work). This is unlike other exchanges where the parties make the deal and go their separate ways to enjoy the fruits of their trade.

Anyway, those principles govern the way I operate as a professional and make me a ‘martian’ relative to my professional colleagues.

Staggered wage decisions and real wages

An annual wage adjustment cycle as exists in Australia means that minimum wage workers have to endure systematic cuts in their real wages more than they would if the adjustments were indexed through the year after an annual review decision.

With inflation being a continuous process (more or less), the annual adjustments by the Fair Work Commission hand employers huge gains and deprive the workers of real income in between decisions. The following discussion and diagram explain why.

Assume that at the time of policy implementation, the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) wage was w1 and there was no inflation. The wage setting authority manipulates a nominal minimum wage (the $ weekly value) and the real wage equivalent of this nominal wage is found by dividing the nominal wage by movements in the price level. Assume that inflation assumes a positive constant rate at Point 0 onwards.

The nominal wage is the $-value of your weekly wage whereas the real wage equivalent is the quantity of real goods and services that you can purchase with that nominal wage. For a given nominal wage, if prices rise then the real wage equivalent falls because goods and services are becoming more expensive.

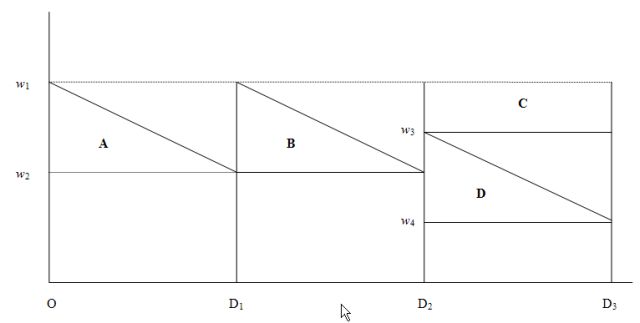

The following diagram depicts the real income losses that arise when wage adjustment is not indexed to the price level on a continuous basis – as is the case when the Fair Work Commission makes an annual adjustment in the FMW:

Over the period O-D1 the rising price level continuously erodes the real value of the nominal wage and immediately before the next indexation decision, the real wage equivalent of the fixed nominal FMW is w2. The real income loss is computed as the area A, which is half the distance (0-D1) times distance (w1-w2).

At point D1 the wage setting authority increases the nominal wage to match the current inflation rate which restores the real wage to w1, but the workers do not recoup the deadweight real income losses equivalent to area A.

The same process occurs in the period between the D1 and the next decision D2, resulting in further real income losses equivalent to area B.

These losses are cumulative and are greater: (a) the higher is the inflation rate; (b) the longer is the period between decisions; and (c) the higher is the real interest rate (reflecting the opportunity cost over time).

Clearly, the patterns of real income loss are different if the wage setting authority adopts a decision rule other than full indexation (that is, real wage maintenance). For example, say it decides not to adjust nominal wages fully at the time of its decision (or in fact at the implementation date of its decision) to the current inflation rate then the real income losses increase, other things equal.

So at time D1 the authority decides to discount the real wage (less than full indexation) and increases the nominal wage rate such that the real wage at that point is equal to w3.

Over the next period to D3, the real wage falls to w4 and at the time of the next decision (implementation time D3) the real income losses would be equal to the triangle D (reflecting the inflation effect over the period D2- D3, plus the rectangle C, which reflects the losses arising from the decision to partially index at D2.

Similarly, one can imagine that the adjustment at a particular time might involve a real wage increase (more than full compensation for the current inflation rate) which would then partially offset some of the real income loss borne in the previous period when nominal wages were unadjusted but inflation was positive.

So if you understand the saw tooth pattern of indexation shown here you will see that the triangles A and B represent real losses for the workers between wage setting points even if real wage maintenance is the preferred policy.

These losses are worse (areas C and D) if there is only partial adjustment. These losses occur because inflation is a more continuous process than the adjustments in FMW and accrue to the employer. The employers are pocketing these wage losses every day because their revenue is geared to the price rises and they are paying constant nominal wages to the workers.

The other problem is that the usual source of growth in real wages for workers is to share in the productivity growth of the nation. Workers not reliant on the annual Federal minimum wage adjustment achieve that through their enterprise bargains although over the last twenty years even those workers have been mostly unsuccessful in achieving a proportionate increase in real wage relative to productivity growth as sequential federal governments have legislated against trade unions and undermined the capacity of workers to bargain on a reasonable basis.

Wage Parity

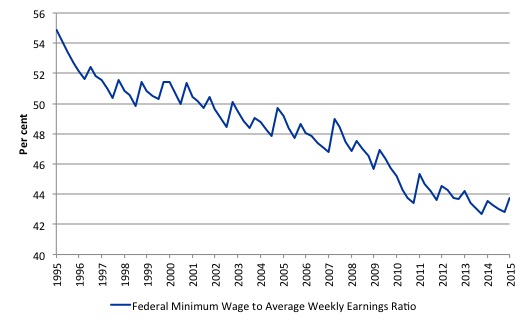

In terms of parities with other wage earners, the following graph shows the ratio of the Federal minimum wage to the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings series provided by the ABS (the latest being for the December-quarter 2013). This series in now bi-annual (previously quarterly). I have interpolated on the basis of the most recent growth.

I simulated this series out to September-quarter 2015 (the quarter in which the latest FWC Annual Wage decision will start impacting) based on a constant growth in earnings (assessed over the last 12 months). The new FWC applies from July 1, 2015 so will be constant over the rest of the 2015-16 financial year.

The logic of the neo-liberal period which encompasses the data sample shown (and then some) was to at least achieve cuts at the bottom of the labour market, given that workers with more bargaining power would put up resistance against generalised cuts.

Successive minimum wage decisions have forced workers at the bottom of the wage distribution to fall further behind in relative terms.

In the December-quarter 1993, minimum wage workers earned around 55 per cent of the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings. By June 2015, this ratio will have fallen to 43 per cent. There has been a serious erosion of parity over the last 18 years.

But whenever the cycle turns down, it is the low-skilled workers who become unemployed first. The neo-liberal logic has not applicability.

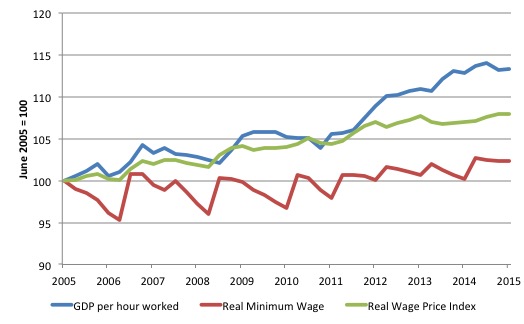

Another way of looking at this dismal outcome is to compare the movement in the Federal Minimum Wage with growth in GDP per hour worked (which is taken from the National Accounts). GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity and tells us about the contribution by workers to production.

Labour productivity growth provides the scope for non-inflationary real wages growth and historically workers have been able to enjoy rising material standards of living because the wage tribunals have awarded growth in nominal wages in proportion with labour productivity growth.

That relationship has been severely disrupted by the neo-liberal attacks on unions, wage fixing tribunals and other legislative initiatives that have eroded the capacity of workers to share in labour productivity growth.

The widening gap between wages growth and labour productivity growth has been a world trend (especially in Anglo countries) and I document the consequences of it in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis.

But the attack on living standards has been accentuated at the bottom end of the labour market.

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (red line), GDP per hour worked (blue line), and the Real Wage Price Index (green line), the latter is a measure of general wage movements in the economy. Th graph is from June 2005 up until June 2015 (indexed at 100 in June 2005).

By June 2015, the respective index numbers were 113 (GDP per hour worked), 107 (Real WPI), and 102.3 (real FMW). This tells us that all workers have failed to enjoy a fair share of the national productivity growth, and that minimum wage workers in Australia are largely excluded from sharing in any of the productivity growth.

The wage tribunals have only allowed the most modest growth in the real standard of living that the minimum wage workers over the last 10 years.

Of-course, like all graphs the picture is sensitive to the sample used. If I had taken the starting point back to the 1980s you would see a very large gap between productivity growth and wages growth, which has been associated with the massive redistribution of real income to profits over the last three decades. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

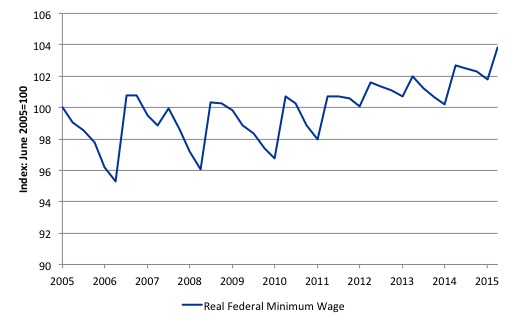

Staggered adjustments in the real world

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) since June 2005 extrapolated out to September 2015 (the quarter in which today’s decision will start impacting) based on a constant (current) inflation rate. You can see the saw-tooth pattern that the theoretical discussion above describes.

Each period that curve heads downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded. Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the Fair Work Commission. If the trough in the saw-tooth lies below the 100 line on the vertical axis then the real wage falls by the end of the period.

If the trough lies above the 100 point then the inflation during the year after the last wage decision has not fully eroded the real wage increase and so there is some modest net real wage increase for Federal minimum wage workers over the period.

In the last two decisions, there has been some modest real income retention by these workers although it depends on how inflation is measured.

But before the workers enjoy the most recent decision to award a wage increase on July 1, 2015, their real wage is lower than it was a year ago as a result of the inflation over the last year.

You can also see the troughs are shallower in recent years than in the past because the inflation rate has moderated as a result of the GFC and the austerity since that has kept economic activity at moderate levels.

So while each adjustment provides some immediate real wage gain for workers, those gains are ephemeral and the inflation process systematically cuts the purchasing power of the FMW significantly by the time the next decision is due – these are permanent losses.

I used the Consumer Price Index to deflate the Federal Minimum Wage to create the real series. The CPI is, in fact, a very limited measure of the cost of living. In May 2011, the ABS published their – Analytical Living Cost Indexes for Selected Australian Household Types – which provided more detailed analysis of the impact of price rises on different household and worker cohorts.

Those on low pay are likely to be significantly worse off than the raw CPI figures suggest.

More drivel from Australia’s national press

The Fairfax media published an article yesterday (June 4, 2015) – Investors queue up for debt bomb party invites – which it shouldn’t have!

The article is written by a seasoned journalist who did an economic degree at Sydney University’s Political Economy program, which is meant to produce progressive thinkers. I wonder what went wrong with their macroeconomics courses?

The article is correct in its conclusion that private bond markets are clamouring for Australian government debt because they know it is risk free and a desirable place to park funds in this era of low fixed income earnings.

We knew that already given Australia issues its own currency and can always service liabilities in that currency. Australia also does not borrow in foreign currencies. It is fully sovereign in that regard.

The author also correctly notes that the clamour for our Government’s debt is in contradiction with “all the hysteria and dire warnings about rising government debt”.

The conservatives have been claiming there is a “debt bomb” that is about to explode. They knew that was a lie but said it anyway because it gave them political leverage amidst a deeply ignorant public.

Where does that ignorance come from? What reinforces it?

Well, one answer is articles like this on.

The author says:

When individuals need to borrow, we go cap in hand to a bank. When AAA-rated governments need to borrow, they hold auctions and let banks, pension funds and others bid for the privilege of lending them money. And investors have been more than willing to come to the party.

The first sentence is fact.

The rest is nonsense. The Australian government never needs to borrow. It issues the currency and floats it freely against other currencies.

It may have set up a host of voluntary constraints to inhibit its obvious intrinsic freedom but they are just regulations or legislations that can be changed at will.

The central bank is a creature of legislation. It could be instructed at any time the government desired to simply credit bank accounts on behalf of the Government with no ‘debt’ instrument matching that transaction.

The author makes a lot of our AAA-rating. The rating is largely meaningless as Japan and other nations have shown in the past. There was no upward blip in Japanese government bond yields when the ratings agencies downgraded its bonds to near junk status some years ago.

Nor when the US was downgraded.

Further, the government can always set yields at whatever level it desires if it insists on issuing debt. It can simply say that they want to borrow X billion at y per cent. If the bond markets don’t like the y per cent then the central bank can fill in for them. That is the way it used to be before the government decided to make the bond issuing system an elaborate system for providing corporate welfare.

The Fairfax journalist then claims that:

Treasury has begun issuing 20-year bonds and recently indicated it is also looking at 30-year bonds. The government has to pay higher rates of interest on longer termed bonds, but they provide greater certainty and could protect us when interest rates around the globe inevitably rise. So what is there really to worry about?

Paying down debts is a form of crisis insurance – best to get the books in order now so that when the next financial crisis hits, you are still deemed creditworthy.

But, as the International Monetary Fund points out in a new paper this week, such insurance comes at a cost, either through higher taxes which distort activity or through the abandonment of social spending, like on infrastructure and education, which would have otherwise boosted social wellbeing.

At which point you know she knows very little about how the monetary system operates and has just been uncritically reading the ‘fiscal space’ paper that I commented about yesterday.

Please read my blog – The ‘fiscal space’ charade – IMF becomes Moody’s advertising agency – for more discussion on this point.

1. There is no meaning to the concept of “crisis insurance” for a truly sovereign government. Such a government can run whatever deficits it chooses, irrespective of whether it ran surpluses or deficits previously.

There are no stock consideration in the capacity of the government to provide a flow of net spending in each period as desired.

2. There is no meaning to the term “get the books in order” for a truly sovereign government. That is a concept that might be applicable to a private sector entity (household, firm) which uses the currency and faces financial constraints on their spending.

3. There is no meaning to the status “creditworthy” for a truly sovereign government. See above. The private bond markets want the debt not the other way around.

4. Governments do not pay off deficits with higher taxes or abandoning social spending. Only misguided governments imbued with fallacious neo-liberal principles do that sort of thing at the expense of the well-being of their citizens. Before the neo-liberal era dominated governments ran continuous deficits which enhanced the prosperity of their population.

Phew! Makes you wonder!

1945 White Paper on Full Employment Workshop – Sydney, May 30, 2015

This is the edited video of my presentation at the Workshop in Sydney last Saturday.

The full workshop video will be available next week.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well that will serve me right for not putting my brain into gear today and just going to the bottom of the article to search out Prof. Mitchell’s musical suggestion. I should of course have tuned into the Workshop video but instead I went to YouTube for this boost to the soul from The Redskins: Keep on Keepin on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=al9CF0qEGq8 . Now I will of course increase my knowledge and critical faculties.

Forgive me if I am not particularly interested in Australian unemployment figures. Could I please hijack your blog by reporting a development yesterday in the UK.

I have been trying to give Osborne the benefit of the doubt in view of the fact that he failed to reduce the deficit in the last parliament to zero as promised in the manifesto. We MMTers know that this is the principal reason why the UK is not as deeply in recession as would otherwise have been the case. (Arguably just about not in recession). So I allowed myself to assume that Osborne did know how the modern monetary system works, and just wasn’t saying so.

Sadly, yesterday, Osborne reiterated his commitment to bring the deficit to zero by 2018 and to be in surplus by the end of this parliament. Now the Conservatives have a mandate they can steam on and just do that. He has already announced £2.2 billion of cuts. As defence is one of these it seems unlikely the UK will meet its obligation to NATO.

In view of the fact (as reported in this blog a few days ago) that the Bank of England clearly understands MMT why does the Chancellor of the Exchequer not?

If the government actually acheives the aim of eliminating the deficit the UK will be thrown into another recession of 2008 proportions.

How can we get through to these numbsculls?

More drivel from Australia’s national press.

Okay, so I decided to read this bit. Couldn’t agree more. Same thing in the UK. The BBC’s economics editor was on TV last night trotting out all the same rubbish we get from the Chancellor. I’ve no doubt the Telegraph, Guardian et all will be similar if I bothered to read them.

Dear Bill

In Canada, the minimum wage is set by the provinces. The federal minimum wage only applies to employees of the federal government. It varies between 10.20 and 11 CAD. Since the CAD is worth 1.04 Australian dollar, you can see that the Canadian minimum wage is considerably lower than the Australian one.

What matters to employers is not only the before-tax income of their employees but also how much they have to pay to the government for each employee. In Canada, employers have to pay contributions to Canada Pension, Employment Insurance and Workmen’s Safety. The cost of an employee to his employer is higher than the before-tax wage that the employee receives.

Regards. James

The federal Australian government NEVER NEEDS to borrow. Anyone familiar with this site would know that.

But it doesn’t mean the fed government does not borrow. Do you know if the government actually borrows?

I mean one hears about projects that are financed by public-private consortiums. These too should be redundant.

I’m having difficulty in understanding what counts and does not count as “Government Debt” so it’s useful to see how much government debt is just ignorance of macroeconomics, etc.

Matt McOsker….Thx for considering my post on “public-sector” job creation, yesterday [perhaps more relevant to Bill’s post today]….your key phrase for me is “How are we going to pay for it?”. I know Bill supports deficit spending but that is a very touchy subject in America, at $17 trillion-and I suspect at first glance it is seen as another massive government program-but I don’t see it that way. For instance HR 1000 is deficit-neutral, and would be paid for by a tiny fraction on all stock transactions. My preference, which I call The Neighbor-To-Neighbor Job Creation Act, is a federally mandated Social Insurance, owned by our employed, to provide a fund to hire/train our unemployed. The job creation in either case, would be a grant-in-aid type to local jurisdictions-preferably with a focus on infrastructure repair. In any case I think the job creation must contain these elements:

1] It is based on the truism that we have far more work that needs to be done in America, than we have persons to fill these jobs….the notion that these are make work jobs is nonsensical….

2] Renewable funding is mandatory….this is not a “jump-start” solution until the market kicks in [the methodology driving our policies in America, today]-and preferably based on the BUFFER STOCK EMPLOYMENT MODEL-an expanding and contracting public workforce-that expands during a downturn in the market, and contracts as employees return to the private sector.

3] The funding is deficit-neutral [for the reason cited above-and politically it would never get off the ground otherwise, in America-and for the reason you cited the “Common voter”.