I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

S&P decision is irrelevant

In the last few days I have read more misinformation and downright lies from financial and economic commentators in the media than I have for the last year. The decision by the irrelevant S&P to get some attention for their corporate profit-making activities by downgrading US government debt has sparked a frenzy of nonsensical “analysis” which is as ridiculous as was the S&P decision. The fact is that the S&P decision is irrelevant as long as the US government makes it so. The danger is that the Government will think there is something to be addressed and the US economy will suffer as a result. As long as the US government realises who calls the shots the S&P decision will be irrelevant.

After seeing the S&P decision pop up on my computer, I tweeted “S&P downgrade US debt – get over it – it doesn’t mean a thing. Just ask Japan. S&P are irrelevant to US gov’t debt dynamics and yields”.

I received instant replies that “yeah it just means we pay higher interest rates, but hey that’s nothing”.

I replied “only if the government lets that happen. The Fed can control that. If they cave in to the ratings agencies then yes. Japan didn’t.”

Later someone said that “Japan has 40 per cent savings rate and fair amount of our debt. That’s why they don’t care”.

There was the skeptical “how is Japan doing these days/years/decades?”. To which I replied to myself – a whole lot better than the US!

But you get the drift – the fears all follow an erroneous understanding of how monetary systems operate – how interest rates are set in fiat monetary systems, the role of government and the discretion that the monopoly issuer of the currency actually has in such a system, and the irrelevance of the ratings agencies to such a government.

The fears all follow from the mainstream economics depiction of the way the monetary system operates that puts the sovereign government at the mercy of these criminal rating agencies. The reality is nothing like that represented by the mainstream economics profession and the fact is that the ratings agencies are at the mercy of the government not the other way around.

I recommend outlawing the agencies entirely – please read my blog – Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies – for more discussion on that point.

You might also like to read – Who is in charge? – for further clarification of who calls the shots in a fiat monetary system.

The problem is that governments lie to the people and hide behind the alleged domination of the ratings agencies and the amorphous bond markets to pursue agendas that they know they would not be able to do politically if they were honest – like cutting pension entitlements.

Take this commentary in the Sydney Morning Herald (August 7, 2011) – Start Fattening the Nest Egg – as an example of the arguments that came out after the S&P downgrade. There are many such articles across the world’s press.

The writer claims that:

BABY BOOMERS have not saved enough for retirement and could face tough government measures aimed at boosting their nest eggs. The government has admitted it cannot fully fund the pension for the unprecedented number of retirees who are set to leave the workforce in the next 10 years.

A significant fall in Australian shares on Friday most likely wiped out last year’s 8.9 per cent average gain by balanced superannuation funds, where most Australians have their retirement savings invested.

It followed the big losses suffered during the 2008 financial crisis, when many superannuation funds were left exposed to the effects of the collapse of the US subprime-mortgage market.

Any sensible person concerned with their future but who didn’t understand how the monetary system works would conclude – the S&P downgrade will damage their retirement income potential and they better save even more now because the Australian government will run out of money. The act of implementing these personal strategies will then further erode aggregate demand and reduce economic growth.

The automatic stabilisers then will push government budgets further into deficit – and the vicious circle of lies would see the call for even more austerity while the rating agencies boost their corporate standing by further threats and downgrades.

Meanwhile more people become unemployed and more people move into poverty.

The reality is that the Australian government is lying to the people when it says it cannot fully fund the pension entitlements that will arise as the baby boomers retire en masse over the coming decade.

What it should say is that it is “unwilling” to fund the pensions which would be equivalent to them admitting that they are cutting pension entitlements. Of-course they will not admit that because they know they would be swept out of office at the next election. No political party will admit to an intention of cutting entitlements.

So instead they lie – and clothe their intentions as a financial necessity knowing that the vast majority of the population will believe them if they say it enough and knowing that the mainstream economics profession will support them and the financial journalists will just ape the nonsense that the economists provide them.

The reality is otherwise. The national government which issues the Australian dollar will always be able to fund whatever legal Australian dollar pension entitlements are in place at any time. What they cannot necessarily guarantee is the on-going real continuity of those entitlements – that is, the quantity of real resources that the pension cheques can buy. That depends on availability of real resources and the productivity of the workforce.

The government can assist in improving productivity by ensuring the public education and health systems are first-class and that there is on-going full employment. Fiscal austerity is the anathema of that sort of productivity-enhancing strategy and represents a deliberate government policy approach which will diminish the future prosperity of the people.

Another example of the appalling reporting was this article (August 7, 2011) – At debt’s door which appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald.

The writers said:

The decision technically means the US is less able to pay its $US14.3 trillion ($13.7 trillion) debt, and makes the world’s richest nation a worse credit risk than Australia, Germany, Britain and the Isle of Man. The House Democratic Whip, Steny Hoyer, said it served ”as yet another wake-up call that we must put politics aside as we work to put our nation’s fiscal house back in order”.

I love it when financial journalists use words like “technical” as if they were getting deep into the bowels of the problem – beyond our simple intuitive grasp.

The fact is that the S&P decision does not technically do anything with respect to the US government’s ability to pay its debts. It is an absolute lie to say otherwise.

The decision doesn’t alter the “credit risk” of the US government. Credit risk is intrinsic to the monetary system not what some corrupt capitalist firm that has been caught out with its hands in the till previously (ratings for dollars!) thinks.

The SMH article also says:

Analysts say it could push up borrowing costs for the US, costing taxpayers tens of billions of dollars a year, and drive up interest rates.

This is the common claim that we address in this blog. It is also a lie.

Note my mention of Japan. Please read the blogs – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates and Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies – for further discussion about Japan.

So let’s first of all look at Japan – an advanced nation with currency sovereignty.

In November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s Investors Service began the first of a series of downgradings of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa rating away. The next major Moody’s downgrade occurred on September 8, 2000.

Then, in December 2001, Moody’s further downgraded the Japan Governments yen-denominated bond rating to Aa3 from Aa2. On May 31, 2002, Moody’s Investors Service cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

The then Japanese Finance Minister responded (with some foresight):

They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.

Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors.

In the New York Times (July 6, 2002) the logic of the rating decision was questioned:

How … could a country that receives foreign aid from Japan have a better rating than Japan itself? Japan, with an economy almost 1,000 times the size of Botswana’s, has the world’s largest foreign reserves, $446 billion; the world’s largest domestic savings, $11.4 trillion; and about $1 trillion in overseas investments. And 95 percent of the debt is held by Japanese people …

Former Moody’s President, John Bohn Jr. had in 1995 claimed that: “We’re in the integrity business: People pay us to be objective, to be independent and to forcefully tell it like it is.” (Reference: Ratings Trouble, Institutional Investor, October 1995: 245).

Later the agencies were forced to admit to the US Congress (at the height of the recent crisis) that they took money from firms in return for their AAA corporate rating. Many of the products the agencies gave top ratings to collapsed as worthless assets in the crisis. The agencies are one of the greatest cons around and can never be considered independent.

How do these agencies approach the rating of sovereign debt? Moody’s defines a rating is “an independent opinion on the future ability and legal obligation of an issuer of debt to make timely payments of principal and interest on a specific fixed-income security”. Similarly, for S&P “a credit rating is S&Ps opinion of the general creditworthiness of an obligor, or the creditworthiness of a an obligor with respect to a particular debt security or other financial obligation, based on relevant risk factors”.

The agencies continually claim that they are providing an indicator of the “probability that the issuer will default on the security over its life…” So when considering sovereign debt as opposed to corporate debt, the agencies are suggesting that as the public debt to GDP ratio rises, the risk that the government will become insolvent rises. And their logic must be that default follows sovereign insolvency even when the sovereign debt is denominated in the government’s own currency. It doesn’t take long to realise that this logic is no logic.

Rating sovereign debt according to default risk is nonsensical. While Japan’s economy was struggling at the time, the default risk on yen-denominated sovereign debt was nil given that the yen is a floating exchange rate.

Once we understand how a sovereign government operates with respect to the monetary system this point become obvious.

First, when a particular government bond matures (that is, becomes due for repayment) the Government of Japan would simply credit the bank account of the holder with the principle and interest and cancel the accounting record of that debt instrument. Simple as that. The banking reserves would rise by that amount and the wealth of the private investor would change in mix from bond to bank deposit.

Second, the relatively large fiscal deficits that the Japanese Government has run since the 1990s just work in the same way – adding reserves on a daily basis to the banking system (as people spend the yen and deposit them back into bank accounts etc). The bond issues are designed to give the private sector an interest-bearing financial asset to replace the non-interest earning bank reserves. The way the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has kept the interest rate in Japan at virtually zero for years now is that they do not issue debt volume of debt to match the reserve-add of the deficit spending. That is, they leave just enough excess reserves in the cash system overnight each day to force the interbank market to compete the rate down to zero. This is a very clever way of ensuring that the longer rates (the so-called investment rates) are as low as they can be.

Third, what if the Japanese Government decided it didn’t want to issue any more debt but still ran the deficits? It has already been established in the recent crisis that the Japanese government can instruct the Bank of Japan to fund its spending. So any net public spending would still occur – day by day – and provide stimulus to the economy. But the liquidity effects would just remain in the excess banking reserves and force the private sector to hold the new net financial assets pouring in each day via the deficits in the form of reserves rather than interest-bearing bonds. The other angle on this that is often overlooked is that the bond holdings of the private sector also constitute an income source – that is, the government interest payments on its outstanding debt constitute another avenue for stimulus. So when the Government retires debt it reduces private incomes.

The Japanese Government is very sophisticated and knew that Government debt was seen as a safe haven during its decade or more of volatile economic times and also realised that the steady and predictable income flow derived by the private sector holding the public debt was a source of security and a positive influence on growth.

So any notion that a government that is running large fiscal deficits and also issuing debt for monetary policy reasons or in the Japanese case (given they have zero short-term interest rates anyway) for risk reduction purposes, might be a risk is ridiculous.

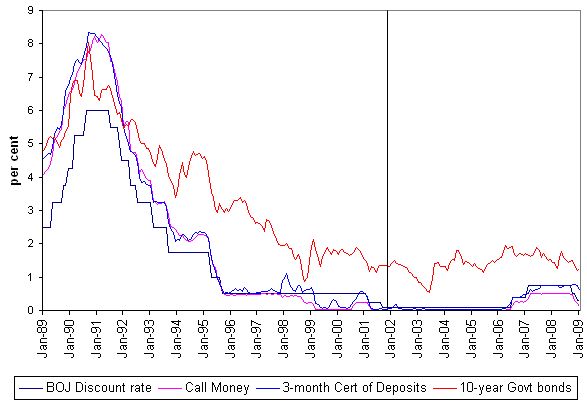

The following graph is a long time-series look at the major Japanese money market interest rates. You will see that over the period that Moody’s was playing stupid downgrading games with the Japanese Government that no interest rate effects were detected. The vertical black line is December 2001.

So the ratings agency decision was irrelevant to interest rates determination – for reasons I will explain.

Note that the logic presented above does not extend to foreign-currency denominated public debt which is subject to exchange rate exposure. Clearly a national government that relies on foreign-currency denominated debt issuance is exposing itself to default risk. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) clearly tells us that a sovereign government should never issue debt in any currency other than its own. But in the Japanese case, the ratings agencies clearly stated they were rating default risk not currency risk.

For Australia, foreign holders of our public debt will clearly face exchange rate (or currency) risk. But that is not related to the decision of the Government to net spend unless you bring the old furphy out that these amorphous hedge funds out there will mark a currency down if a Government borrows to much. That is possible but unlikely. Suggesting that this will push up interest rates (to provide some cover for the currency risk) assumes that the Government is stupid enough to keep borrowing from markets that want to impose this type of penalty.

If that was the case, then you will understand by now that this behaviour is entirely voluntary given they do not have to “finance their deficits”. So it would not be the deficits that were pushing the rates up but the stupidity of the neo-liberal constrained Government policy whereby it has to match net spending with debt issues ($-for-$). Purely voluntary – totally unnecessary – and very stupid.

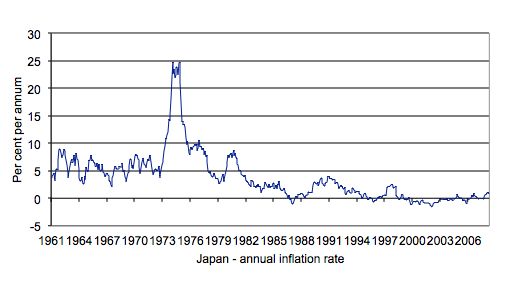

Consider the next graph which shows the annual inflation rate in Japan up until 2006. For those who worry about large deficits being inflationary and/or that the ratings agencies will push up costs in the economy please explain this graph.

So no inflation emerged even though the budget deficits remained relatively high as a percent of GDP.

Further there was no impact on real GDP growth. The following graph shows the annual rate of real growth in Japan from March 1991 (at the onset of the asset price crash) through to the December quarter 2006.

The property crash caused a severe contraction in household consumption and private investment spending which culminated in a brief real contraction in 1994. Once the stimulus from the expanding budget deficit began to work real GDP growth regained momemtum.

By 1996, the same calls for austerity (fears about public debt ratio etc) that dominate the policy debate today were rampant in Japan and the government eventually bowed to political pressure and raised taxes in an attempt to reign in the budget deficit.

The public contraction on top of very fragile private sector spending – akin to the situation that most nations face today – caused a massive contraction in 1997 and 1998 – which increased the budget deficit (via the automatic stabilisers) and added to the public debt ratio (given both debt was rising and GDP was falling).

That was the situation that Moody’s then started to play games by downgrading the sovereign debt. Fortunately, the Japanese government did not take any notice of the agencies and realising the mistake of 1996-1997, expanded their net spending again. The renewed fiscal stimulus saw real GDP grow very strongly in the ensuing years despite the rating agencies decision.

The Japanese government never had any trouble finding buyers for the debt it was issuing, they held complete control over interest rates, inflation fell, unemployment remained relatively stable and real GDP growth was strong through the period of the downgrade.

The decision by Moody’s was rendered irrelevant by the Japanese government who just exercised the power they had as a sovereign issuer of the currency.

You might wonder what happened in 2002? The recession that occurred then in Japan was largely driven by an export collapse (remember the US went into recession during this period) and a tightening of net public spending. This then provoked a fall in private investment spending and a rising saving rate. It had nothing to do with the ratings decision.

Once exports recovered and public spending support resumed the economy then grew relatively strongly despite the lower sovereign debt ratings.

What are the responses to the arguments presented above?

First, they say that Japan is a special case because the government sells most of its debt to local savers (very little to ) and that the Japanese are loyal and have a high saving propensity.

It is true that the US offers a much greater proportion of its public debt to international investors who accumulate US dollars, in part, because the US runs a current account deficit (to the material benefit of its citizens). Japan typically runs current account surpluses.

The trade flows are tied in with the intentions of the exporting nations to accumulate claims denominated in the currency of the importing nation. If, for example, China decided it had “enough” US-dollar denominated assets then it would not be prepared to export to the US on the current terms of trade (which in real terms are all to the advantage of the US – they can get more real goods and services from China than they have to sent back. Living standards are only meaningfully defined in real terms).

The upshot would be that the US current account deficit would decline because the import terms would be less favourable to the US consumers and firms and the private domestic bond market in the US would probably expand. That is, they would become more like Japan. None of this implies that the size of the bond market – international or domestic ultimately matters – it doesn’t. Remember, sovereign governments ultimately do not need to borrow to spend.

But this first concern – the size of the local bond market – is a very common point that is raised. The problem is that it is irrelevant. To understand why we have to consider how the design of the monetary system impacts on interest rate determination.

Second, and related, is the claim that the rating agencies are demonstrating their relevance in the way that things are turning out in the EMU. Yields on sovereign debt in Greece, for example, have risen dramatically after the bond markets withdrew their interest in purchasing the assets. The downgrades from the rating agencies exacerbated the problems for the Greek government.

Once again this is a very common point but again it is based on a misunderstanding of how interest rate determination is dependent on the design of the monetary system.

We cannot compare what might happen in the US to what is happening in Greece (as an example) because the monetary systems in each is different.

The EMU governments have:

- Surrendered their currency sovereignty and effectively spend a foreign currency.

- Have no capacity to issue their own currency at will and thus rely on taxes and/or borrowing to fund their net spending.

- Face interest rates determined by a central bank they do not control (directly or implicitly via legislation/constitution).

In such a system the term structure of interest rate – which describes the spread of rates from the short-term policy rate (set by the European Central Bank) to the long-term interest rates – is determined by a combination of the ECB policy decisions at the short-end of the yield curve and private investment market expecations about inflation and default risk at the longer-maturities.

The ECB could control rates at the longer segments if it chose to – by fixing rates and declaring an intention to buy any debt at that rate – but the individual member states cannot compel them to do that. The member nations surrendered their control when they joined the Eurozone.

The US, Japan and most other nations have:

- Exclusive monopolies over the issuance of their own currency and can always spend in that currency as long as their are real goods and services available for sale.

- Do not have to borrow to fund net spending over taxation. In general, a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

- Have the power to control the central bank and its interest rate setting decisions and/or its asset purchase decisions. In other words, despite the labyrinth of regulations/laws that governments have erected to present the chimera of central bank independence, at the bottom of it all is that the government rules and has intrinsic powers it can call upon to use the central bank to do what it wants.

In this type of monetary system – the fiat currency system – it is the government that rules always. The central bank sets the interest rates at the short-end of the yield curve and the term structure follows expectations of inflation risk rather than default risk.

The private bond markets know that the US government will not default on its debt for financial reasons. The investors have also guessed that the Tea Party blowhards are unlikely to face the chagrin of the public and push a voluntary default by refusing to pass the debt ceiling. We say how gutless they were last week. Even so, the President and Treasury in the US still had ways around the debt ceiling if the Republicans had have had the nerve. The fact they chose not to use those means (coinage tricks, instructing the US Federal Reserve to wipe off its public debt holdings etc) doesn’t mean they wouldn’t in the extreme situation.

Once you understand that distinction between monetary systems you can readily appreciate why the bond rating downgrades in Japan in the late 1990s and early 2000s did not impact on rates or anything else.

Finally, I loved this “assessment” from Barclays Capital in their client newsletter (thanks Marshall).

Here was their advice to their clients yesterday (in part) after the S&P downgrade:

The S&P ratings agency downgraded the US long-term sovereign credit rating from AAA to AA+ with a negative outlook on 5 August. What does it mean for global FX? In our view, there are three issues to consider: what does it imply for risk appetite in the short run, what will the policy response be and what does it mean for USD prospects in the medium to long run? We expect it to initially lead to a further rally in “safe haven” assets, in particular the JPY and CHF, which will likely be met by some policy response to weaken those currencies, but that will limit the appreciation not stop it.

Some questions:

1. To be clear isn’t JPY = Japanese Yen?

2. Isn’t Japan also excluded from the Triple-A debt club? You will note from this map that Japan is also not in the “Triple-A debt club”.

3. Doesn’t Japan have a public debt ratio over 200 per cent which is more than twice the ratio in the US at present?

4. What the F##K?

Which in more polite language asks – how come Japan is now a “safe haven” and its public debt is a “safe haven asset” and the US treasury bonds are not. Answer: there is no logic in any of this other than there is no default risk for sovereign nation debt and the markets know it and they also know they want as much sovereign debt as governments will issue.

Further, recent bond market yields tell us that in net terms none of the investors are selling of US government debt. They know how irrelevant the S&P decision is. Please read my blog – Day by day the evidence mounts – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

The first thing the US government should do today when they wake up is enact legislation to outlaw the ratings agencies. The second thing they should do is increase their deficits and introduce a Job Guarantee. The third thing they should do is enjoy the political credit that will flow from reducing unemployment.

I am rushing to catch a plane this morning so that will have to be it until tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

That’s the wrong answer!

US treasury bonds are no longer a safe haven asset because they still have a debt ceiling. The problem’s not been resolved (it’s merely been postponed for a few months) and the president doesn’t seem to realise he has the power to increase the money supply without taking on more debt.

And even if he does realise it and act accordingly, US treasury bods may still not be a safe haven asset – for though there will be no credit risk, there will be a short term devaluation risk. This is less likely to be a problem for Japan because it’s a net exporter.

That would probably be unconstitutional – but even if they could do it, outlawing them is not the best solution. Making them irrelevant is. Barclays Capital’s assessment regarding ¥ as a safe haven shows the process has already started. News reports that US treasury bond yields actually fell since the downgrading seems to indicate that S&P’s ratings are widely regarded as dodgy.

Bill,

To add to your points on rating agencies’ relevance and validity, there is also their compulsion to genericize instruments of very different natures into their existing (proprietary) ratings categories. In this case the square ‘government debt’ peg is squashed into the round ‘corporate debt’ rating categories hole. If they insist on rating government debt, however pointless that exercise may be, then at least they should be good enough to use sensible descriptors. Perhaps ratings of SCI and SCU, for Sovereign Currency Issuer or Sovereign Currency User. And stop there.

I noted your “coinage tricks” phrasing, and got queasy thinking about the parallel to the hacking of GW analysts’ e-mails and the controversy that was manufactured from the word choice that was found therein. I don’t think anyone advocating from an MMT perspective in regard to US policy should be too sanguine about the availability of the large denomination coin authority remaining open to the Treasury as a functional alternative. Now that they are aware of the possibility, the Austerians will almost certainly try to kill or geld the enabling statute as soon as Congress reconvenes. I doubt that Geithner would put up much resistance.

“It has already been established in the recent crisis that the Japanese government can instruct the Bank of Japan to fund its spending.”

What’s the evidence that the BoJ is actually taking instructions from the government?

Dear anon (at 2011/08/08 at 17:44)

“can” doesn’t mean “actually”.

best wishes

bill

Low yield currencies are “funding” currencies and high yield currencies are “investment” currencies. Hedge funds are short the low yield and long the high yield. So when they delever, it places downward pressure on the high yield and upward pressure on the low yield.

This is why the yen is a “safe haven”. But this also applies to the U.S. dollar, so don’t be surprised if the dollar gains from the downgrade.

Totally agree Bill. Outrageous that the frauds at S&P think they need to play policeman in the global markets after their appalling part in the GFC.

The sad and unforgiveable impact of their actions will be to hurt the already very fragile consumer confidence both in the US and elsewhere which will indeed have tangible negative effects to economies.

Ironic that the very political system that gave them virtual immunity from prosecution (while the Banks suffer the lawsuits) is the one that they are now stabbing in the back.

Bill (or anyone):

“First, they say that Japan is a special case because the government sells most of its debt to local savers (very little to ) and that the Japanese are loyal and have a high saving propensity.”

MMT considers the current Japanese deficits as facilitating the private sector’s ability to net save, right? So, the high savings propensity that supports the bonds in Japan must be tied to the high debt-to-GDP ratio, right?

Anyone with a more organised brain than me want to state this relationship in clearer language — I’d appreciate it.

Phil

@ Max

What you just wrote is very interesting, but I’m not sure I fully understand. Any chance you could be more specific?

When WHO delevers? The governments?

Why does it follow that the Yen is a safe haven?

There was never any real risk of the US defaulting, even if Congress had failed to increase the debt limit. All of the competent reporting on the Treasury Department’s likely courses of action made it clear that Geithner would prioritize debt service payments above all other payments.

In addition, a strong argument can be made that the 14th amendment to the US constitution gives the treasury Department no other choice. The debt “shall not be questioned.” If the Treasury can make its debt service payments, than it must make its debt service payments.

Had the debt ceiling not been raised, the probable result – given that Obama and Geithner were unlikely to take the Big Coin approach, for political reasons – would have been that a bunch of other payments would not have been made – including payments to people least able to afford the cuts. These cuts would have further starved the economy of sorely needed income and spending.

Unfortunately, rather than stalwartly defend the need to continue those payments and programs, the Obama administration, pursuing its own austerity line, chose to misrepresent the battle over the debt ceiling as a battle over whether or not the US would default.

One might say, then, that it’s no wonder that a credit ratings agency like S&P, whose analysts are reportedly not the swiftest folks out there, would be snookered by these political shenanigans into thinking that the US actually came close to defaulting. However, given the fact that it was widely reported in the major mainstream media during the last week of the debate that failure to raise the debt ceiling would not lead to default, I suspect even the S&P folks were not duped by the politics. So they are now just making up this default risk out of whole cloth, for either political or business reasons.

And none of the above touches on the large point that S&P gave AAA ratings to mortgage-backed derivatives that disintegrated into sludge in 2008.

Alan Greenspan reads Bill Mitchell:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6vi528gseA&feature=related

That clip in itself is worth the downgrade, methinks…

Did anyone see this comment from Greenspan:

“The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEKhxdeadk0

Greenspan understands the basics of MMT??

Excellent post, as always! Now I can just send the link around rather than write my own, thanks!

Allow me to reinforce that japan’s deficit spending adds the yen balances to boj accounts that then buy the jgb’s.

The concern over whether those yen balances are held by residents or non residents has always escaped me.

http://www.moslereconomics.com

The salient point is in Bill’s lead: ” As long as the US government realises who calls the shots the S&P decision will be irrelevant.”

The White House is occupied by Chicago School guy. He may not have studied economics there but he certainly breathed the air and drank the water which is all grotty with hard money cant and laissez-faire mythomania. He really believes those great guys on Wall Street that give to him so prolifically in the hoydens den of “campaign finance” know how to make the world a better place: they have certainly made his world a better place. These idiots, from Wall Street to the White House seem to really believe that they are doing gods work. Obviously Mammon is their god.

Unfortunately the US remains a rich country and this slow bleed could go on for years. It leaves one hoping the markets explode, just to get the pain over with: if the non-financial economy is to be left to starve, I’d just as soon get on with it and get it over one way or another.

Bill:

Excellent article; one of your best, I think for all of us students.

This one pretty much whacks down every loose nail in the mainstream coffin.

You and your colleagues provide my sole intellectual solace in trying to survive through this mass insanity.

Thank you.

On your blog (and Warren Mosler’s) I always read comments that seem suprised when a Treasury/Fed official seems to understand the basic tenets of MMT. I think that position is rather naive to say the least. These individuals have dealt with monetary issues and reserve accounting their whole lives – it is impossible that they would not have figured out the rather straightforward concepts that MMT describes.

The issue here is purely political. It is impossible for for an acting politician, treasury official, or central bank official to come out in the open and call a spade a spade, for the simple reason that the language of MMT sounds, to the uninitiated, mad – especially more so when taken as a soundbite. “Deficits don’t matter!”, “We can always print more!”, “Deficit needs to increase!” are not soundbites that sell a political career.

That is the biggest challenge that MMT faces – that it is not a politically palatable idea. Let me delve deeper – it is not a philosophically palatable idea. The biggest victory of neoliberal economic policy is that it melds so perfectly with the Judeo-Christian moral tradition of Western civilisation, that presents suffering, sacrifice, and the destruction of the self as intrinsically noble and worthy. Thus ideas of austerity, forced unemployment, and recession are seen as justifiable punishment for our transgression of debt-fueled indulgence.

MMT writers will argue that this suffering is not necessary; deficits can fill the spending gap; millions needn’t be unemployed; growth can return, tomorrow, if we wanted it to. Economically and logically sound as that response is, it simply doesn’t satisfy the ingrained desire for cruel divine justice that Western society still, unfortunately, holds so dear.

Put simply – everyone would be somewhat uncomfortable if we got out of this financial crisis with no-one suffering for it.

And that is why MMT will never be mainstream.

In other news, did anyone catch the great Paul McCulley interview on Bloomberg.

http://www.bloomberg.com/video/73591226/

He said sovereign governments should run deficits “without apology”.

AK

“These individuals have dealt with monetary issues and reserve accounting their whole lives – it is impossible that they would not have figured out the rather straightforward concepts that MMT describes.”

I don’t think that’s true. Bill and Warren — among others — are always writing anecdotes about how when they encounter central bankers and government economists they don’t understand the fundamentals of the monetary system. They often tell anecdotes of how they lead these folks around by the nose until, lo and behold, they agree with them — but then they quickly forget the implications of what they have just agreed with.

“That is the biggest challenge that MMT faces – that it is not a politically palatable idea. Let me delve deeper – it is not a philosophically palatable idea.”

I don’t think this is remotely true. An MMT-informed political party could offer the population a lot. I don’t think what you outline is some deeply ingrained ‘moral imperative’ so much as it is a reflection of the times we live in. If we look back on history we see many instances in which governments offered the population hope rather than damnation.

The most obvious example would be Communism — which essentially controlled half the world a few decades ago and was remarkably popular in Europe. A better example would be the Northern European Social Democracies in the early and mid twentieth centuries. There was some amazing visions among them and, in contrast to the Communists, they initiated them quite well.

(There’s also the rather less palatable example of Fascism which, disgusting as it may have been, was offering people a new political program and a new form of social organisations — remember one of Hitler’s key promises was to wipe out unemployment and put Germany back to work… which he did quite successfully).

Once again, what you’re pointing to is a malaise among the contemporary political classes; not some deeply held Christian conservatism at the heart of Western Man.

Bill,

“has already been established” necessarily means action has been taken in the relevant context

“When WHO delevers? The governments?

Why does it follow that the Yen is a safe haven?”

Hedge funds. It’s not that low yield currencies are intrinsically safe, but when speculators liquidate their positions those currencies rise. So they move inversely to stocks.

AK

“These individuals have dealt with monetary issues and reserve accounting their whole lives – it is impossible that they would not have figured out the rather straightforward concepts that MMT describes.”

Philip P.

“I don’t think that’s true. Bill and Warren – among others – are always writing anecdotes about how when they encounter central bankers and government economists they don’t understand the fundamentals of the monetary system. ”

Is this still true? The anecdotes in Warren’s book about the 7 deadly innocent frauds took place a long time ago, in the 1990s. Warren’s first book on all this came out in 1993. Given the fact that he has had spectacular success in his career, surely any book of his would be widely read? Even in the 1990s, all Warren had to do was ask the Italian government financial official the right question, when the scales fell from his eyes, he and all his colleagues realized that there was no way the Italian gov’t was going to default, and celebratory capuccino was had by all. The fundamentals of MMT are not rocket science, even for a functional mathematical illiterate like me. Given all this, how can career accounting types be ignorant of MMT?

Philip questions AK’s contention that in the US “The biggest victory of neoliberal economic policy is that it melds so perfectly with the Judeo-Christian moral tradition of Western civilisation, that presents suffering, sacrifice, and the destruction of the self as intrinsically noble and worthy. Thus ideas of austerity, forced unemployment, and recession are seen as justifiable punishment for our transgression of debt-fueled indulgence.”

Philip’s counter examples of Communism and the social democracies of western Europe may not be relevant here in the US because, believe it or not, the fundamental world view of the Puritans who founded New England continue to be important for large segments of the population. Much of Europe has managed to move beyond the Judeo-Christian outlook, but the US lags behind in this, in part because of the work of corporate propagandists in launching the culture wars as a weapon of mass distraction – see Thomas Frank’s “What’s the Matter with Kansas?” which showed how Republicans used the abortion issue to get people to vote against their own economic interests. I just hope AK isn’t right that MMT will never be mainstream.

Hi Bill;

First off, thanks for one of the best posts I can remember.

But. The following paragraph is capable of confusing people. The same point confused me over at the MMP primer and Professor Wray said I was right to bring it up.

‘First, when a particular government bond matures (that is, becomes due for repayment) the Government of Japan would simply credit the bank account of the holder with the principle and interest and cancel the accounting record of that debt instrument. Simple as that. The banking reserves would rise by that amount and the wealth of the private investor would change in mix from bond to bank deposit.’

When you say ‘…the Government of Japan would simply credit the bank account of the holder…’ aren’t you leaving out the simultaneous credit to the reserve account of the private investor’s commercial bank? It’s true that the next sentence only makes sense because this reserve account has been credited. But MMT rookies like me need it to be spelled out. Otherwise, we may think that the bank deposit *itself* is the increase in ‘banking reserves.’

Cheers

AK said:

“And that is why MMT will never be mainstream”

I think Some Guy contradicts that assertion, with some authority, in his answer to Sean’s question in Bill’s previous post “A totally confected crisis”:

It was applied worldwide, when it was called functional finance and Keynesian economics. It led to the greatest prosperity the world has ever seen, before or since, the post-war golden age…

That was a time when 2% unemployment was enough to threaten a government’s hold on office.

@ Cathy Mason

The New Deal was, in all essentials, in line with the northern European Social Democratic outlook. It may have been a little watered down but it was still based on progressive principles (in Europe these were often called ‘radical’ rather than ‘progressive’, but they mean the same thing).

I don’t see much point in drawing conclusions based on religious demographics. Lutheran Sweden adopted strong Social Democracy while Catholic Ireland remained staunchly conservative. Meanwhile Catholic France instigated a strong welfare state and voted in strong Communist blocs into government in the post-war years.

The causes of these differences had nothing to do with religion. In France, for example, Communism was popular because (a) ever since the French Revolution the French people have been quite radical in their outlook and (b) many Communists were heroes having been resistance fighters during the Nazi occupation. While in Ireland the Catholic Church wielded great power in a semi-feudal society and crushed/co-opted any reforms that manifested themselves.

As for Sweden, it had a very strong working class movement — being a predominantly working class society. And the US? It had a very well organised political system and a tendency to deal with problems in technocratic terms.

Religion or religious ideas explain very little here as far as I can see.

Oh, and let’s not forget that, as Christopher Lasch has shown, American progressivism had its roots in the Protestant tradition:

http://www.amazon.com/New-Radicalism-America-1889-1963-Intellectual/dp/0393316963

In the case of a figure like William Jennings Bryan it even adopted a preacher-man posture. After he said that they “would not nail him to a cross of gold” he used to outstretch his arms as if he were being crucified. You don’t get more Christian than that — and those were the actions of a man calling for soft money and greater prosperity for all.

Religious doctrines of Sin and Redemption work both ways, it would seem.

This is good and it makes sense but the problem I have is that if the vast overwhelming majority don’t know, or don’t understand, or refuse to accept, any of this then we have disasters. It is kind of like going over a company accounts and finding something that makes you conclude it is undervalued. You can’t make money until the rest of the make comes to the same conclusion. Likewise while all this makes sense, to a man (and woman) all countries seem to be run by people in denial of all of this. Ultimately the majority has its way. So the real question is not so much about how clueless these people are it is how change can ever occur?

My 2c is that given that 2008 didn’t cause a major rethink of how things work (other than a very superficial mea culpa and then back to business) it seems like only something that is much much worse, an actual world collapse, would force a change in the thinking of governments.

I think AK makes a great point about our Puritanical roots and even Calvinistic self flaggelation as somehow noble but this is not a mythos entirely shared by the younger generation. Yes the 50 and older crowd still has waaaay too much of that in them and they are still in charge in most cases but things are a changin’ (and this is what scares so many of our elders)

To me the power of MMT is it takes the focus off finance. Any group can do anything they want provided they have the real resources to do it. Monetary cost is NOT a hinderance. Do you really want red wine flowing through your water fountains (to steal an analogy from Prof Wray)? Well if you have enough land to grow the grapes and enough people to smash them and enough barrels to make the wine yes you can. Is it a good use of land and other resources? Thats a different question. Can you really afford to be the policeman of the world? Well if you have access to enough oil/fuel to run your planes, tanks and armored vehicles plus enough willing and able bodies you can.

“The reality is otherwise. The national government which issues the Australian dollar will always be able to fund whatever legal Australian dollar pension entitlements are in place at any time. What they cannot necessarily guarantee is the on-going real continuity of those entitlements – that is, the quantity of real resources that the pension cheques can buy. That depends on availability of real resources and the productivity of the workforce.”

My admittedly ignorant questions is, what happens to Australian ability to purchase real resources via foreign exchange if it spends too much on domestic programs and consequently devalues its currency? Please indulge me, as I have no understanding of the effects of MMT on foreign exchange. Obviously. 🙂

A citation to other posts is fine, thanks.

hi Bill

A friend pointed me to your writings. I went through the introductory material on MMT and faced one confusion, which happened to crystallise while reading this article (section quoted below):

—- The national government which issues the Australian dollar will always be able to fund whatever legal Australian dollar pension entitlements are in place at any time. What they cannot necessarily guarantee is the on-going real continuity of those entitlements – that is, the quantity of real resources that the pension cheques can buy. That depends on availability of real resources and the productivity of the workforce. —-

From what I understand, money, whether fiat or gold-backed is meant for enabling exchange.

Increasing supply of the exchange-medium does not necessarily create wealth or feed ppl. Basically, what I am trying to say (hopefully clearly) is that I reckon having the govt print money and distribute it for well-intentioned causes/projects seems to gloss over the immense, real-world difficulty of the process of wealth-creation.

New wealth does not necessarily arise when new money is created. From what I understand of the world, we need a competitive, creatively destructive, bottom-up market in which economic actors can compete to win customers and thus (as a by-product) create wealth in the process. Money (fiat or gold-backed) is simply a lubricant to facilitate exchange, but abundance of it does not guarantee wealth-creation.

If the above is reasonable, then expecting a govt to intervene in a top-down manner to put the unemployed back to work and to do it competently, seems to be a forlorn hope. If top-down economic decision-making/guidance could work reliably, then it would be plausible to advocate such a policy. But empirics are not on our side.

i dunno if my blathering makes any sense, but this is as far as i have got and would appreciate your inputs.

thanks for your time.

kal

P.S. It is not that I am against reducing suffering, but the most likely outcome of govt driving/guiding economic investments is that the extra money printed will lead to sub-par wealth creation and the currency will essentially be inflated. And if it leads to wealth being destroyed, the currency will suffer even more.

Kal,

Nice to see you here. Stick with it – it takes a while before the scales fall from the eyes and you see how it works.

You are quite correct. Money does not create real stuff automatically. However not having enough money circulating *will* stop real stuff from being created.

If the non-government sector saves overall (people are saving their money, and the banks are unable to find enough people to borrow money) then the amount of money circulating decreases. It’s like the oil in a car engine – if there isn’t enough the engine loses power an eventually seizes up.

What MMT points out via circuit theory is that money is endogenously created. Credit Money expands and contracts based on private sector saving and spending decisions. Classical economics assumes a fixed amount of money – and they are surprised when we have bubbles.

When Credit money contracts, capacity in the real economy goes – the good stuff along with the malinvestments.

To counter that the government needs to accommodate those extra savings with an expansion of Fiat Money.

The challenge is to design a dampening system that allows malinvestments to resolve safely without destroying too much of the good stuff at the same time.

The Job Guarantee is one of the best ways of doing that as it maintains skills, motivation and a level of spending throughout the Credit money contraction period. People will likely have lost some income as they move from a higher paid job to a maintenance job on the Job Guarantee scheme, but they won’t have lost everything.

Remember also that the government doesn’t have to do the organisation for a Job Guarantee. It just has to provide the Fiat money to pay the workers that are not otherwise engaged. It should be perfectly possible to delegate the decision on the type and nature of the work to charities, voluntary organisations and other social enterprises. There is no need for a tall centralised bureaucracy.

hi Neil, thanks for your reply.

There are some parts I understand and agree with, but some parts I don’t get and would like to discuss in more detail if possible. Would it be ok to do so on this forum or is it preferred that commentors discuss further via email?

cheers

kal

Best here so that others can find it.

Sorry about the slow response, Neil.

I agree completely that “not having enough money circulating *will* stop real stuff from being created”. To that, I would add the counter-balancing statement that “having too much money circulating will cause damage.” So, I guess the issue is how much money should be in circulation. But I think that is why the Fed exists (as I understand it).

Are we in agreement thus far? Or is there some part I got wrong? =)

cheers

Kal