In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Should we be concerned with a fall in the Nikkei?

Up until a while ago, it was the government bond market that was going to crash in Japan if the government didn’t do something serious about implementing fiscal austerity. The bond market is still very healthy and yields are very low around the world and in Japan negative on some government bonds and bills. With that scare campaign defeated by reality, the doomsayers are now moving into making predictions about equity markets. The latest is that the Nikkei is about to crash unless the Japanese government significantly tightens fiscal policy some more. Remember this is in the context of a 3 percentage points rise in the sales tax in April which left consumers flat and real GDP growth collapsed in the second-quarter as a result.

I last wrote about Japan in this blog – Japan’s growth slows under tax hikes but the OECD want more.

And a week before that I wrote – Our poster child keeps exposing the myths – which provided updates on the Japanese bond markets and the role played by the Bank of Japan as the major purchaser of Japanese government debt at present.

I emphasised that we should never believe anyone who says the bond markets call the tune when it comes to a currency-issuing government. The central bank in that sort of nation always calls the tune. It can set the yields and other rates at whatever level they choose, including zero, by using their currency-issuing capacity (which is infinite) to demand any volume of debt that the government chooses to issue.

So that just about puts the sovereign bond market to rest. Meltdown theories, governments running out of money, investors fleeing, international investors turning their backs on the nation – whichever way the doomsday scenario is expressed on a recurring and often hysterical basis, there is nothing in it.

So with that in mind, the doomsayers now have a new target in sight for Japan. The private share market. Apparently that is about to collapse and engender mayhem and Japan will sink into the sea and disappear from the wealthy nations’ list.

There is just a few slight problems with that prophecy. First, it wouldn’t matter much if the share market went south. Second, share market investors are not so dumb as to be influenced by state of Japanese government debt levels, especially as they can read the newspapers and realise that the Bank of Japan has infinite (minus one yen) currency issuing capacity.

But still, in a Bloomberg article yesterday (September 22, 2014) – Nikkei Crash a Risk Seen by Posen If Abe Blinks on Tax – US economist, Adam Posen who is the President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, claimed that unless the Japanese government relents from its current fiscal austerity program, the share market in Japan will collapse, inflation will rise and real incomes will fall – hence undermining any chance of recovery.

In my previous recent blogs we saw that the first of the scheduled rises in the sales tax as part of the austerity plan has returned Japan to 1997 by creating the worst decline in real GDP since the GFC.

Japan’s economy suffered its worst contraction since 2011 in the second quarter as consumer spending on big items slumped in the wake of a sales tax rise …

Japan’s consumption tax was increased to 8 per cent in April as part of an ill-considered drive to fiscal austerity and in the second-quarter national accounts results we see private consumption plummetting and private capital formation slowing.

With that in mind, the Japan government should be seriously reconsidering the decision to introduce a second-round of sales tax increases.

Adam Posen claimed that deferring further fiscal consolidation would be a disaster. I think the opposite. He is not, in fact, an hysterical free market type despite his position as President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

In 2010 he published a working paper – The Realities and Relevance of Japan’s Great Recession: Neither Ran nor Rashomon – and wrote:

Whether in Japan in the 1990s or in the United States in 2008-10, heated discussions take place as though the short-run effects of fiscal policy were in dispute. They should not be. Fiscal policy works when it is tried.

So his views are more nuanced than the hysteria you get from the usual advocates of fiscal austerity.

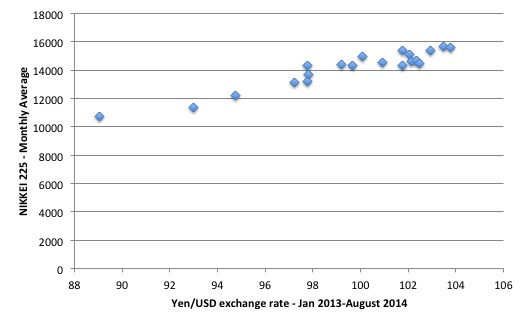

His main claim is that the Nikkei Stock Average 224, the share market index in Japan, has grown substantially since 2013 (from 10,688.11 on January 1, 2013 to 16,205.90 on September 22, 2014) is:

largely due to foreign investors banking on Abenomics.

What is the evidence for that?

The article claims that “Net purchases of Japanese stocks by overseas investors amounted to 14.3 trillion yen ($132 billion) through August since Abe took office in December 2012”. You can check the data at – JPX. I had a look and the figure looks about right.

It is clear that overseas investors (both institutions and individuals) have been large players on the Tokyo and Nagoya exchanges over the last 2 years or so.

But of course we do not know about the motivations that underlie the equity speculation decisions. It is a difficult argument to make that speculative investment will be encouraged by an economy that is falling off the cliff.

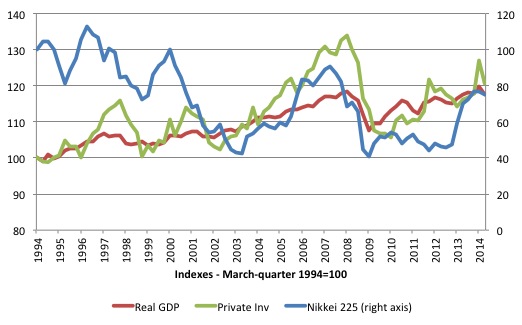

Strong equity markets normally accompany a positive growth enviroment. The following graph shows the movement of the Nikkei 225 (quarterly averages), real GDP and private capital formation all indexed to 100 at March-quarter 1994. The Nikkei is on the right-hand axis.

While eye-balling graphs can be a dangerous exercise, it seems that the three series move in some sort of pattern together with the Nikkei usually lagging growth (turning point comes before the real spending shifts).

I haven’t time today to go into the theories that suggest this – they relate to expectations of expected future dividends as corporate earnings rise in an upturn. The opposite occurs when sentiment weakens and the private investment (in real capital) cycle undermines real growth.

Keynes referred to “animal spirits” when discussing general movements in sentiment among the participants in the economy. He thought share prices would rise when people determined that the economy was likely to improve and were willing to undertake risky positions in financial assets such as shares.

So it could be expected corporate earnings or generalised sentiment. The evidence for these theories is mixed and some nations fit the prediction more than others.

As an aside, In Chapter 12, Section V of the General Theory, Keynes wrote of the behaviour of the professional investor in terms of a ‘beauty contest’:

Or, to change the metaphor slightly, professional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

In other words, share market investors would consider the price of a share not in terms of what they thought was its fundamental value but what they thought all the market participants would consider the value to be.

Which suggests that share market participants are less likely to even include the fiscal position of the government in their evaluations of risk and return. But if they did, it would appear they would be more concerned with the fiscal stance in relation to its impact on real expenditure rather than nuanced meanings of a shift in the public debt ratio.

The beat up about public debt ratios is something that bored financial market commentators rave on about. Most people who put their money at stake are more concerned with corporate earnings, security of yields etc.

A government that is announcing that it will put up the sales tax a second time after the first rise (of 3 per cent) killed consumer spending would be sending a signal to equity markets that corporate earnings are likely to slow and generalised expansion of investment opportunities would weaken.

But Posen thinks otherwise and was quoted, by way of conclusion that:

Failure to face up to the fiscal situation is not going to be taken well by those investors,” Posen said, noting that the subsequent decline in the yen could force up inflation enough to hurt the real incomes Abe wants to spur.

First, the aim of the Bank of Japan is to increase the inflation rate at present anyway. A few weeks ago, the BOJ succeeded in pushing the short-term interest rate below zero which means that it is lending yen to the large banks and paying them to do so – the BOJ paid more for three-month and six-month bills than their redemption value.

How can it do that – that is, guarantee itself a loss? Easy, it creates yen ‘out of thin air’ – it can supply as much yen to anyone as it chooses. Losses on trades like this have no impact on its operations.

Last Friday, the BOJ bought one-year government bonds at negative yields so it is extending its operations along the maturity curve. The aim is according to the BOJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda to ensure that:

… the monetary base will be doubled in two years

He said that during a speech on March 21, 2014 at a conference held at the LSE – How to Overcome Deflation.

The belief that the monetary base expansion will lead to higher inflation is of course part of the mainstream mythology. The extra money has to be spent before it can impact on the price level.

With fiscal austerity being pursued, the chances of consumer and private investment spending taking up the slack left by they contraction in public spending are slim. It would be far better for the government to jack up its fiscal deficit and increase real incomes that way in the short-term and push the inflation rate up through aggregate spending outstripping supply.

Second, as the NIKKEI 225 has risen, the yen has fallen! The following graph shows the movement in the Nikkei 225 since January 2013 until August 2014 (vertical axis) against the Yen/USD parity over the same period.

The influx of foreign investors into the Japanese share market hasn’t been a positive influence on the Yen/USD parity.

So it is far from certain that the Yen would fall further if the private investors reduced their commitment to the Japanese equities market. It might but then again …

Third, would it matter if the exchange rate fell? Clearly, it would push the inflation rate in the direction the BOJ desires. It would also stimulate Japan’s trade position. Any influence on the exchange rate would be small and finite and the damage being wrought by the fiscal austerity on real GDP and national income is of a much larger order of significance.

Fourth, would it matter if the Nikkei 225 (or any of the other indices fell)? Not a lot. There is a view that it would damage consumption expenditure because of the wealth effect – the falling share values reduce private wealth.

Wealth effects are usually estimated to be very small.

As noted above, it is highly unlikely that private investment will be stimulated at a time consumption spending is being hammered by the rise in sales tax and real GDP is contracting on the back of fiscal cut backs. The opposite would be the prediction.

Most share market trading is not in the service of funding new companies but shuffling wealth in bets among the financial sector.

But at any rate, the government can always offset any shifts in private spending by expanding its own net position.

Fifth, do equity investors really make their decisions by consulting the fiscal position of an advanced nation? See the argument above.

The other thing to note is that government bond yields are now very low (in historical terms) all around the world. For savers who typically might have opted to have larger government bond portfolios, the search for higher returns have moved them into the riskier equities market.

This is likely to explain the upsurge in foreign interest in the Nikkei. What other option have they got?

Conclusion

The Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe wrote an Op Ed last week (September 18, 2014) – The Next Stage of Abenomics Is Coming – where he boldly predicted that the sharp decline in economic growth in the second-quarter of 2014 would reverse as the Government pushed ahead with its austerity measures.

The next step – his “third arrow” of policy moves willl involve major “structural reforms”, which will include opening up energy markets for competition, allowing more foreigners to enter Japan, deregulating the agricultural sector (farm consolidation etc), reducing labour market protections for workers in prescribed new companies etc – all policies that other nations have tried with little success.

I measure success here in terms of achieving stable economic growth, low unemployment and underemployment, declining income and wealth inequality and reduced poverty rates.

Adam Posen should be recommending that the Japanese government forget about its fiscal austerity plans and instead stimulate the economy and provide a strong corporate profits environment upon which the Nikkei is driven.

Not that I care at all for the gambling casino that we call sharemarkets.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“….Adam Posen…claimed that unless the Japanese government relents from its current fiscal austerity program, the share market in Japan will collapse, etc…”

That “unless” should most probably be an “if”.

Thanks once again, Bill.

When I think of Japan I am always reminded of soldiers returning from some tropical island many decades after the war is over.

I imagine to a man they are shocked that the war economy has entered the family home.

Does it really benefit a family if they can go out and buy a tank / car ?

GDP has no relationship to people.

Its growth merely makes debt dynamics more sustainable.

You are a supercapitalist Bill.

The detachment of people from each other in Japan reflects a deep spiritual pain.

Go ahead and win the great war of GDP.

If i knew how i would short Japan.

Apart from being overweight, having a big mouth and knowing nothing about economics, what other qualities are required when it comes to being President of the Peterson Institute?

I could of course say something more intelligent, but it would be lost on supporters of the Peterson Institute, so what’s the point? No point in casting pearls before swine as it says in the Bible.

Hey Dork,

1.When I think of Japan ,I think of Sushi Train,Karaoke,and Toyota,not wars.

2.Sorry I’m not aware that Japan was at war or had been threatened by terrorist.

3.Does if you’re trying to pick-up the kids from school,and you’d have to be more specific on the tank,but

could be yes ,if it’s for water collection , no if it’s an army tank ,I’ve heard their awfully rough on the road surface

and almost impossible to get the garage door close at home without cutting the cannon off.

4.Okay,some people may not need to know about it ,although if it’s turning negative then i say lots of humans will be affected

5.c4

6.Yeah, I can’t believe the amount of advertisements I see every-time I visit Bill’s Blog.

7.Now,that’s a hard one,for I’m not into spirits and I’m guessing you’d love a wine, but

anyway you do know it’s mainly a small Island nation.

8.Okay again,after-all it’s better than losing..c4

Thanks Bill

“How can it do that – that is, guarantee itself a loss? Easy, it creates yen ‘out of thin air’ – it can supply as much yen to anyone as it chooses. Losses on trades like this have no impact on its operations.”

As I’ve debated why this isn’t more obvious to people I concluded that part of the problem may be improper accounting practice on the part of central banks of monetary sovereigns. When a commercial bank generates a deposit as part of lending it correctly generates a new asset for the loan and a new liability for the deposit because it has a contingent liability to supply base money if the deposit is moved (via writing a check for example). Central banks do exactly the same accounting when they generate new base money for loans or quantitative easing or whatever. The difference for them is that they have no actual liability associated with the deposits they create. So the proper offset to the asset should be an increase to a capital account rather than an increase in liabilities. They are effectively “mining” new money, just as if they were mining gold, which should rightly be considered a profit from operations and booked that way.

When the U.S. first went off the gold standard, the Fed should have booked a windfall profit by debiting their liability for outstanding currency and crediting some sort of earning or profit account. I’ve checked and can find nothing of the sort. They have continued to account for new money generation as an increase in liabilities, compounding their mistake.

I think if they did this proprly there might also be some interesting implications for treasury debt since the Fed turns over excess profits to the treasury at the end of each year.

@laerreal

I would like to have what you are smoking……….

You are not on my cloud man – thats for sure……….and I do like wine , my economics is coming around to the ghost of Christmas present you see – as Calvinist efforts to save and blow various Darian schemes has proven itself to be a cathastrophic experiment again and again and again.

I have come to the conclusion that the Tudor capitalist experiment was the greatest disaster ever to befall humanity.

I feel sorry for Japan and its society as it was one of the first Asian societies to embrace the satanic mill back in the 19th century .

And now look at it ?

The poor Japanese society which always valued beauty cannot even see the night sky now.

The more yee guys win the great GDP war the more people will be crushed by it.

Even the so called opponents of Neo-Liberali$m can’t get it right.

Here is a quote from the Australia Institutue:

“Australian debt are at record-low levels (and likely to stay that way for years), further reducing the burden of net interest payments. In short, Australia’s ability to manage public debt is very strong”

What interest burden ? This lot might as well merge with the right-wing think tanks they supposedly oppose.

Central Banks do the accounting properly. You’re not reading it right.

The main central bank asset is actually a contingent asset – taxpayer equity. It is the capitalised value of the country to infinity!

So when Central banks issue reserves they mark up ‘Other Assets’ – representing a charge against taxpayer equity – and issue a liability which is transferred to the commercial banks. That becomes the commercial bank asset and the central bank’s liability.

There is no flow here. It is just a balance sheet expansion. Similarly with commercial banks. The implicit contract to convert to/deliver central bank liabilities is a separate issue IMV.

Alan Dunn –

The interest on government bonds, plus the interest the RBA pays to banks minus the interest banks pay to the RBA.

So the Australia Institute is correct.

Bill’s error (pointed out by Vassilis Serafimakis) highlights a great irony:

Adam Posen thinks that if the Japanese government relents from its current fiscal austerity program, the share market in Japan will collapse, etc…

But in reality it’s likely that unless the Japanese government relents from its current fiscal austerity program, the share market in Japan will collapse, etc!

Neil,

It would be interesting to have a more in depth conversation than is possible here, but let me respond to your points. I would truly be interested in understanding your view better, but honestly can’t make sense of several of your comments. I’ll restrict my comments to actions of the U.S. Federal Reserve. I presume that other central banks account in much the same way, but since I have no real knowledge of their actions, I’ll stay with the one system that I can speak about somewhat knowledgeably.

“Central Banks do the accounting properly. You’re not reading it right.”

Not reading what right exactly? Their accounting statements? They are pretty straight forward. Deposits with the Federal Reserve are explicitly listed as a liability and not some sort of equity, if that is what you were trying to say.

“The main central bank asset is actually a contingent asset – taxpayer equity. It is the capitalised value of the country to infinity!”

I’m not sure what you are trying to say here. There is no such asset on their balance sheet (which would not be unusual for a contingent asset), but to be a contingent asset, there would have to be at least some theoretical way to derive a value from it. There is nothing in the Fed’s charter that would permit them to do so and frankly, there is no need to do so since there is no contractual obligation for the Fed to convert Federal Reserve notes into anything else. I suppose you could assert that congress could always use its taxing authority to provide some benefit to the treasury, but to what end? Has this contingent asset ever been realized in any part since the end of the gold standard?

“So when Central banks issue reserves they mark up ‘Other Assets’ – representing a charge against taxpayer equity – and issue a liability which is transferred to the commercial banks.”

There is no such transaction that I can find anywhere in Fed statements. The total of “Other Assets” on the Fed’s balance sheet is only a very small fraction of its assets and not the huge amount that it would need to be if the Fed was accounting in the way you seem to suggest here. The assets on the Fed’s statement are mostly either financial instruments that have been purchased with the funds they created or outstanding loans to banks. And bank deposits are accounted for one-for-one as liabilities (not equity) on the Fed’s balance sheet. See for example their most current statement (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1).

“That becomes the commercial bank asset and the central bank’s liability.”

Certainly bank deposits at the Fed are bank assets, but why exactly should they be considered a liability for the central bank? That is mostly my point. There is no contractual obligation to convert those deposits into anything else. When the U.S. guaranteed conversion to gold it was entirely reasonable to consider deposits as liabilities, but not it is not. I’m certainly not alone in this thinking. See for example Benes, J. and Kumhof, M. (2012) “The Chicago Plan Revisited,” International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 12202 which says:

‘In this context it is critical to realize that the stock of reserves, or money, newly issued by the government is not a debt of the government. The reason is that fiat money is not redeemable, in that holders of money cannot claim repayment in something other than money. Money is therefore properly treated as government equity rather than government debt, which is exactly how treasury coin is currently treated under U.S. accounting conventions.’

which may be how treasury coin is treated, but is most emphatically not how bank reserve balances are treated.

“There is no flow here. It is just a balance sheet expansion.”

Balance sheet expansions are a combination of an increase in some asset and an offset that is either a new liability (as for example when you take out a loan or assume some other contractual obligation) or an increase in equity which typically results either from selling shares in return for an investment or from profits realized from operations. Currently, the Fed accounts for its expanded balance sheet with an increase in liabilities rather than an increase in equity and I’m simply pointing out that this is incorrect.

“Similarly with commercial banks. The implicit contract to convert to/deliver central bank liabilities is a separate issue IMV.”

There is a fundamental difference in the money created by commercial banks and the money created by the Fed. The former undertake a real contractual obligation when they create money. If that money is withdrawn as cash, they have an obligation to supply that cash. If it is transferred via check, the bank has a real obligation to provide reserve funds when the check clears. In contrast, the Fed has no corresponding contractual obligation for funds deposited at Federal Reserve banks. They are convertible into exactly nothing (except perhaps vault cash, which similarly represents no real liability to the Fed). Again, that was not true when such funds were backed by gold and this form of accounting was entirely reasonable at that time.

It is something of a truism in accounting that contractual obligations must be represented as liabilities and that all liabilities have an associated contractual obligation. This is precisely why commercial banks represent deposits as liabilities, so this is not “a separate issue”, whatever you mean by that. An this is precisely why reserve deposits should NOT be represented as liabilities, even though that is exactly what the Fed’s balance sheet shows.

Aidan – There is no interest burden because the bonds are denominated in $AUS – and last I checked the RBA had a monopoly on their issue.

With respect to the interest rate the RBA can choose any rate it likes by simply adjusting the liquidity of the exchange settlement accounts.

The person that wrote the article for the AI knows better and that’s what is so disappointing.

Alan Dunn – Interest is paid on the bonds, therefore your claim that the debt burden doesn’t exist is a lie.

The fact that there are no circumstances under which we can’t pay it doesn’t change anything.

I’m not sure what you mean about adjusting the liquidity of the settlement accounts, as it seems to me any attempt by the RBA to do so would impede their function. However, the RBA can alter the interest rate easily enough, though doing so has consequences in the real economy.

You’ve been here long enough that you should know better and that’s what is so disappointing.