Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Manufacturing in Australia can survive if it shifts focus

Last week, the Holden Motor Car Company, a division of General Motors announced it was intending to close its Australian operations down in 2017 after having operated on a continuous basis in one form or another since 1856. The decision has led to outbreaks of nostalgia, worries about our national identity (since when has a national identity been tied up with a foreign-owned capitalist firm?), and calls for more government subsidies to the industry that has been in decline for years. The problem is that thousands of jobs are directly and indirectly impacted by the closure (although there are some years before the full brunt will be experienced) and that is an issue that the government has to manage through appropriate policy interventions. The real issue is that the current thrust of aggregate (macroeconomic) policy does not provide one with much confidence that the government will introduce appropriate responses to the closures. I offer some thoughts by way of an introduction in this blog.

The first point is to provide some perspective.

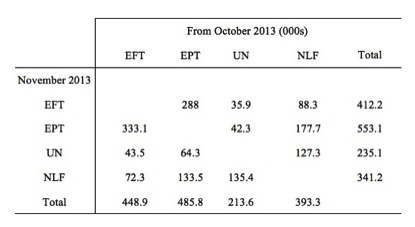

The Table shows the flows in the Australian labour market (in 000s) between the various labour force states: Employed full-time (EFT), employed part-time (EPT), unemployment (UN) and Not in the Labour Force (NLF). Please read my blog – What can the gross flows tell us? – for more discussion on how gross flows data varies from the standard labour force results published every month.

The flows from the labour force to NLF are shown by the sum of the NLF row. The flow the other way is the sum of the NLF column.

The data shows, for example, that between October 2013 and November 2013, 333.1 thousand people flowed from full-time employment into part-time employment while 72.3 thousand flowed outside the labour force.

Similarly, 35.9 unemployed people flowed into full-time employment, 42.3 thousand flowed in part-time employment, and 135.4 exited the labour force.

The point of the table is that the labour force flows every month are large relative to to the size of the labour force of 12,348 million.

I considered some of the issues surrounding the viability of manufacturing in this blog – What you consume or what you produce?.

I noted that in general I do not support protection policies to subsidise industries that have been in operation decades. Having said that I acknowledge that Australian subsidies to the car industry are not unique and are not even large in per capita terms.

We learn in this article – Do other countries subsidise their car industry more than we do? – that “international standards our support [of the automotive industry] is modest”.

For example, the US and various European nations heavily subsidise car manufacturing relative to Australia. Of-course, for example, if you are a purveyor of French cars (not mentioning anyone) then one gets a highly engineered vehicle with more sophistication that the equivalent Australian-produced car for around the same price, courtesy of the French government. Merci beaucoup!

But, in this context, I don’t buy the arguments from the “free market” lobby such as the Institute of Public Affairs that we should have a level playing field to ensure sustainability driven by competition. Where actually is the playing field level? Germany, the US, France etc – all exporting cars into our market.

I also note at the outset that the big foreign-owned car manufacturing companies are experts at triggering the emotional response in various nations that accompanies threats to close their operations. They know that governments are highly compromised in these situations and are prey for to demands for larger cash handouts.

I have never understood the progressive support for handouts to foreign-owned multinationals in return for a temporary promise to keep the factory doors open.

In general, tariffs and other forms of protection just provide massive profit subsidies to foreign capitalist interests and provide disincentives to invest in best practice, high productivity, high real wage capital.

The evidence is clear – they do not sustain growth in employment or long-term certainty of operations.

In the late 1970s a major Australian government report (I can no longer find the reference to it) said that the levels of protection to car manufacturing in Australia were so high that the Australian government could “save” outlays by closing the industry down and paying the same wage bill to the workers. Meanwhile all the rest of us consumers were getting cars that were of no quality or reliability match to the Japanese imports.

Some industries might be considered to be of strategic importance – such as the steel industry – in times of war you need to build tanks (do you anymore?). In that case, tariffs are still not useful. Procurement decrees requiring defense contractors to buy local steel would be help to reach scale but transparent subsidies and even nationalisation might be required.

Further, if we do not like the labour or environmental practices of some of our trading partners then we can deal with that by government to government dialogue, which may mean the Australian Government (legitimately) bans some imports and/or provides consumers with adequate levels of education and information so that we will also not purchase unfair traded goods.

My dislike for government handouts to multinational or domestic capitalist firms which effectively operates to allow returns to be privatised and losses to be socialised is not based on any idea that the government has limited funds, which is the standard objection.

The Australian government can clearly afford (in a financial sense) to offer whatever dollars its likes to these firms. My objection relates to the desirability of encouraging that sort of public-private economic activity over other uses of those real resources. I don’t like the Australian public sector underwriting the profits of North American capitalists.

Also, at the outset, this discussion in no way should be seen as diminishing the costs borne by the workers in the industry closure regions. The evidence is that without adequate transition policies workers who lose their jobs suffer disproportionately relative to the benefits the rest of us get from the cheaper and better cars.

If there is hope that the plant can return what an economist might call “normal profit” (meaning its current use is not wasteful – that is, a better use of the resources cannot be found), then the Argentinean solution of worker takeover might be aided by government.

I agree with the unions here, as outlined by Chris White in his blog – Disastrous GMH closing – that:

So, GMH pulls out of Australia after years of financial assistance and, reportedly exporting on average profits at $50 million per year. All of those dollars originate in the muscle and brain power of the workforce as a whole across 3 or 4 generations. The Australian people deserve some recompense. What will GMH do with the sophisticated tooling that the Australian people have paid for, at least in part?

That capacity should not be lost. It is clear that the motor vehicle industry has been a public-private partnership for the entire life of the sector.

While the car companies will claim the return has been the employment generated, I would argue that the technology development and tooling are also part of the return we should expect.

I will come back to that point in a moment when I outline how the manufacturing sector can survive in Australia.

The general point is that as a private capitalist industry closes and moves to where there is cheaper labour that presents an opportunity to the nation to harness that labour in more productive and forward-looking sectors. It does require a policy framework based on what I have called a Just Transition approach.

Economic restructuring at a regional level is always painful and the decline of manufacturing usually hurts specific cities/regions. In a Commissioned Report that I co-authored modelling the transitions away from coal-fired power to renewables, we noted that a just transition policy recognises that people and ecology are both important.

The just transition policy approach can be applied to any industrial restructuring. A just transition ensures that the costs of economic restructuring and the shift to new industries do not fall on workers in declining industries and their communities.

A just transition in any declining region requires government intervention and community partnerships to create the regulatory framework, infrastructure and market incentives for the creation of well-paid, secure, healthy, satisfying environmentally-friendly jobs with particular attention to appropriately meeting the needs of affected workers and their communities.

Please read my blogs – The Budget (what else) and a parrot or two and Would the Job Guarantee be coercive? – for more discussion on this point.

The government should also ensure that these structural shifts occur at a time when the overall economy is strong. It is virtually impossible for a worker displaced from a manufacturing job to get a new job easily in a stagnant economy.

This is one of the fallacies that the world is caught in at present. The IMF/OECD/EU etc rave on endlessly about the need for structural reform and fiscal consolidation. The latter prevents the effective implementation of the former. They would be able to shift workers from “inefficient” uses to other more desirable uses (for example, get rid of the coal export industry and energise (excuse the pun) the renewable sector if the labour market was very tight).

One of the problems with the current debate is that it is focused on car production when I would prefer to have the debate about the future of manufacturing per se.

I read an interesting news report a few months ago (August 7, 2013) about the growth of Norwegian manufacturing in recent years which I think provides a context for considering the demise of our domestic car production and also a vision for the future.

The Reuters news report – Oil boom drives Norwegian manufacturing to new peak – which said that:

Norwegian manufacturing output surged to a record high in the second quarter, moving firmly past levels last seen before the global financial crisis, as the booming oil industry keeps the economy on pace for solid growth.

The Report indicated that the traditional manufacturing sectors were being squeezed (by high labour costs coming from the bouyant energy sector but that oil and gas manufacturing was booming.

Norway is an exporter of oil and gas and enjoys strong external conditions in these sectors. Norway does not build motor vehicles.

The – International Labor Comparisons – provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that when compared to the US (index of 100), Norway’s hourly compensation costs in manufacturing in 2012 were 178 (that is, 78 per cent higher), while Australia was 134.

Australia is also a small, open economy with a strong mining sector at present pushing up the exchange rate and labour costs which is undermining the viability of other export-oriented sectors.

The clue is for manufacturing firms to ride on the back of the export sectors that are enjoying strong world demand and relinquish investment in areas wehre we clearly cannot compete with other nations (such as, motor vehicles).

There is evidence that some firms are increasingly retooling to orient towards the mining and construction sectors (although a report today suggested the boom in construction in Australia related to the mining sector is coming to an end).

That is the future of manufacturing not cars.

In the Melbourne Age article (December 15, 2013) – Big players unlikely to survive unless the dollar drops – written by economics correspondent (Peter Martin), we read that the common element in the struggles of some of our well-known firms (Holden and Qantas) is not the carbon tax; nor “rapacious unions” but the exchange rate.

Peter Martin wrote that:

The dollar is the common thread in the death spirals of Qantas and Holden … In the quarter of a century to January, 2010, the Aussie averaged US72¢. In recent months, it has been US105¢. It has been great for car buyers and great for travellers. A foreign car that cost $20,000 now costs $14,000. An overseas air ticket that was $2000 now costs $1400.

For companies like Holden and Qantas, on the edge before the dollar soared, it means anything they try to sell overseas costs 45 per cent more …

One way or another we will have less buying power next Christmas. Either the dollar will be dramatically lower, allowing us to compete again, or more Australian firms will fold, causing a recession. It’s time to talk seriously about how we can bring the dollar down.

I considered the issue recently in the blog – Manufacturing employment trends in Australia.

A major point established in that blog was that for Australia movements in competitiveness are driven by the shifts in the nominal exchange rate rather than disparate inflation trends between Australia and the rest of the world.

The dollar will come down (and is) as the record terms of trade falls. But there are other controllable factors which are maintaining a higher value of the dollar than might be considered desirable.

In discussing- The Exchange Rate and the Reserve Bank’s Role in the Foreign Exchange Market – the RBA note that other factors include:

… relative rates of return on Australian dollar assets, changes in the relative risk premium associated with investing in Australian dollar assets, and more broadly, changes in investors’ appetite for taking on risk. Anecdotally, there have been a number of periods since the float when relative rates of return were seen as being a major influence. One such episode occurred in the late 1980s, when Australian real interest rates were much higher than those overseas and the exchange rate rose sharply. The second was in the late 1990s, when Australian real interest rates fell below those in the US and the exchange rate depreciated. The third was in the first half of the 2000s, when Australian real interest rates were again notably higher than those in the major economies, as the major economies experienced a downturn and monetary policy was eased in these countries. Since mid-2009, relatively high real interest rates in Australia compared to the major economies have again likely influenced the appreciation of the Australian dollar.

While the RBA Governor was trying to ride the Australian dollar down last week, in his November 20, 2013 speech – The Australian Dollar: Thirty Years of Floating – and more recent statements he has made to the press, it is clear that he is not prepared to implement the monetary policy necessary to achieve a significantly lower dollar.

The fiscal and monetary policy settings in Australia are wrong at present and they are both contributing to well-below trend growth and rising unemployment on the one hand and a higher dollar on the other hand.

Our cash rate of 2.5 per cent, while very low by our historical standards is well above equivalent rates in other nations.

It is clear that combined to the uncertainty in other markets that has shifted sentiment towards the acquisition of Australian dollar-denominated financial assets, the on-going interest rate differential (with stable inflation rates) is putting upward pressure on our exchange rate.

It is also obvious that fiscal policy is too tight and with the state of the external and private domestic sector spending it is constraining real growth to the low 2 per cent range when trend growth is around 3.25 per cent per annum.

The result is that employment growth has been flat for the last two years and failing to keep pace with the underlying population growth. Accordingly, unemployment has been rising steadily over the last year.

Some of the slack performance is no manifesting in these headline corporate closures.

So I agree that it is “time to talk seriously about how we can bring the dollar down” and the solution is relatively simple.

1. The RBA should cut target rates to close to zero.

2. The Treasury should increase net public spending by at least 1.5 per cent of GDP.

3. The Treasury should scrap all tax system incentives which encourage speculative behaviour in real estate markets.

4. The Treasury should focus the net spending increase on the provision of state housing and public employment.

That would go a long way to improving the economy.

Conclusion

A strong economy with low levels of unemployment can handle structural transitions more easily than an economy where there is already at least 15 per cent of the willing labour force either unemployed, underemployed or discouraged (hidden unemployed).

Further, attacks on higher education and technical training institutions by both the federal and state governments in Australia in the name of “saving public money” are mindless attacks on our future and undermine our capacity to develop best-practice manufacturing.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The European car assembly system is not centered around the nation state !!!

For example France is seeing continued declining production for labour theory of value reasons.

Morocco is now part of former French companies (Renault ) supply chain.

Production is shifting east of Germany and now beyond into Russia.

This can be contrasted to 1960s/70s typical supply chains – for example the old British car industry centered around a rectangular box of a few 100km with Coventry at its center.

Now the Vauxhaul plant in the UK gets much of their parts from Poland via the channel tunnel !!!

The Euro free banking system (in particular Londons oil focus) needs & uses the car Industry to regulate scarcity in the union as the true function of a capitalist system is not to produce goods which are useful to the majority.

Iceland burns more diesel on is fishing fleet then its road transport for a reason.

Its not a member of the IEA and not a member of the EU.

If it were you would see a very different energy balance.

A Irish like energy balance sheet where we burn energy on European added value toys before the energy can be made useful.

Forced car sales via free banking activities is a crucial part of the EU entrepot as it is a simple means to regulate scarcity in the interests of the financial sector.

Look at Londons balance of payments…its income from the rest of the world and especially the EU declined during the start of the economic crisis.

Now that its collecting more interest on the money supply rather then depending on credit expansion (Ulster Bank free banking operations) in the euro area it can only burn the oil in a more direct fashion in its home market.

The UK is the only growing large car market in the EU for this reason.

We now live in a oil standard rather then gold standard world.

If so lets pour oil down their throats by banning car consumption in various new national autocracy systems of the euro periphery.

It will be a sort of modern Marcus Licinius Crassus moment.

The financial sector won’t know what to do with the surplus.

If they are to burn it a massive car boom would be needed in England destroying what remains of their once green and pleasant land

I have to say my previous predictions have been proven correct.

http://www.smmt.co.uk/2013/12/november-new-car-registrations-overtake-2012-full-year-total/

The car industry is a legacy of the Keynesian war economy…….as a result its the easiest method to burn through the capital base thus maintaining scarcity and therefore the financial sectors ascendancy over all life.

The Irish will buy 70,000 new private cars this year alone – that more vehicles then what the Germans used to invade France !!

We in Europe have lived under a constant war economy for at least 100 years !!

The car Industry is the chief physical mechanism through which this evil operates.

sorry – Autarky rather then autocracy.

Perhaps a anti auto-cracy is a better term.

In a humane distributionist economic system cars would have a very minor function in economic life.

Mass car production is a feature of our present Capitalist state fueled at this time by oil.

The best definition of the Capitalist State I have come across : “A society in which the ownership of the means of production is confined to a body of free (economic) citizens not large enough to make up properly a general character of that society , while the rest are dispossessed of the means of production and are therefore proletarian , we call capitalist ”

Belloc

Cars maintain that crucial difference of wealth via the mechanism of waste.

I love and value your exhaustive work immensely, Bill, so please take the next line as a form of endearment! 🙂

As usual, this is incredibly long-winded 🙂 … but it talks all around a concept that hit me from day one.

In scaling up from a tribe to a nation, the hardest things to conserve are:

1) affinity, that YOUR people are your greatest value;

2) the REAL return-on-coordination that comes as a benefit to and consequence of affinity.

Sure, we’ve lost both affinity, and hence return-on-coordination. (In ALL large economies. It’s largely a problem of system scale outracing old, mostly tribally-developed methods.)

The only question that matters is this.

“What methods can return us to national affinity, and systemic loyalty?”

(“Over the rampant treason we have now?”)

“What methods can return us to national affinity, and systemic loyalty?”

Why?

Shouldn’t better questions be asked?

* What are the people of Earth trying to achieve for their family, their species, all life and the planet it resides on?

* What problems will we face, moving from religion, nationalism, war and tribalism towards enlightenment, sustainability of life and of the technological wonders we have conjured up, and how do we best utilize (for the greater good, of course) the hive mind (internet) we have developed?

And more on topic, if we have vehicle manufacturing plants and we’re not building high-end electric (or other sustainable) cars (given our high-ish wages AND incredible logistics and export costs), then it stands to reason that those workers and tooling should be used for something else entirely, doesn’t it?

One of the better posts. Great blog.

Dear Dork, fancy meeting you here. It’s a small cyberworld :0)