It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

External economy considerations – Part 9

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to publish the text sometime in 2013. Our (very incomplete) textbook homepage – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice – has draft chapters and contents etc in varying states of completion. Comments are always welcome. Note also that the text I post here is not intended to be a blog-style narrative but constitutes the drafting work I am doing – that is, the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change as the drafting process evolves.

Chapter 21 Policy in an Open Economy: Exchange Rates, Balance of Payments, and Competitiveness

This material updates the work already done on Chapter 21 that appeared in the following blogs:

- External economy considerations – Part 1

- External economy considerations – Part 2

- External economy considerations – Part 3

- External economy considerations – Part 4

- External economy considerations – Part 5

- External economy considerations – Part 6

- External economy considerations – Part 7

- External economy considerations – Part 8

Today, I am just continuing filling in the gaps in the Chapter. Not much time today – see.

21.7 Currency crises

[CONTINUING THIS SECTION FROM LAST WEEK – PREVIOUS MATERIAL IN LAST POSTS LINKED ABOVE]

The South East Asian Debt Crisis 1997

The last major currency crisis in the 1990s began in 1997 in the South East Asian nations of Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Indonesia and, later, spread to the industrialised East Asian nation of South Korea.

In the two decades leading up to the crisis, the SE Asian nations had attracted large capital inflows and grew rapidly. The period of rapid growth, which started in the late 1980s was accompanied by high private saving ratios and strong investment. Further, inflation was low and the governments were largely running fiscal surpluses.

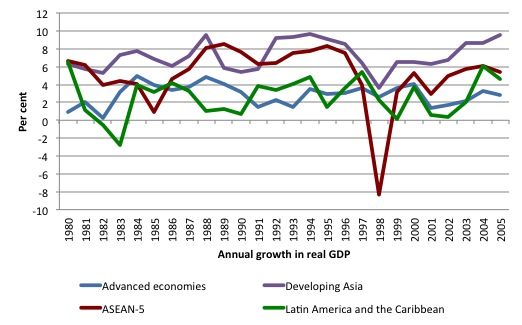

Figure 21.6 compares the annual real GDP growth rates for several blocks of nations including the ASEAN-5, which is comprises: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. You can consult the IMF World Economic Outlook database for full descriptions of the other groupings.

Figure 21.6 Real GDP growth in South East Asia, 1980-2005, per cent per annum

They were considered by the IMF and the World Bank to be models of sustainable development and the expression “The Asian Miracle” was used to describe the rapid growth and rising living standards, particularly in the so-called four “Asian Tiger” economies of Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea.

The multilateral organisations mistakenly considered the rapid growth was the product of fiscal rectitude and free market dynamics, which they considered diverted resources to their highest value use and allowed these nations to be internationally competitive.

However, the reality was different. The Asian nations built their growth strategy based, which began in the late 1960s (with Japan) on a mix of industrialisation, mercantilism and strong state-imposed industrial policies.

In nations such as South Korea, the state played a major role in the development process and defied the advice offered by free market economists at the IMF and the World bank with respect to their development strategy. The latter group considered trade-led growth would only come if a nation exploited its comparative advantage.

However, the South Korean government selected and supported several key sectors to be their growth engines, despite none of them having any relative resource advantage (for example, chemicals). The textiles sector in Korea had indicated that a chemicals industry would support their own development.

The governments, in fact, interfered with the “market” in many ways. They provided credit at below market prices to targetted sectors. Substantial tax breaks were given to firms to increase profits and investment. Protection was provided to local firms against import competition. The state invested heavily in public research and development and shared the results with industry.

By the early 1990s, capital resources were shifting from the Tigers to China and India as a result of the cheaper labour resources available. The growth of China and India challenged the export supremacy of the other Asian nations such as Malaysia, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand, which had led the Asian growth phase in the late 1980s.

The shifting investment and rising export strength of China, in particular, reduced the growth rates in the Tiger nations. Several other shocks occurred in this period which undermined the miracle.

First, the Chinese renminbi and the Japanese yen were devalued. Second, the US Federal Reserve increased interest rates which pushed up the value of the US and placed strain on the currencies which were pegged to it. Third, the fall in export earnings was exacerbated by the large fall in semiconductor prices (falling 36 per cent between 1993 and 1999).

The growth phase was also accompanied by a boom in real estate prices, which was fuelled by significant short-term foreign currency loans, increasing the risk exposure of the private sector reliant on export incomes to service the debts.

The crisis proper began in Thailand in July 1997. The Thai baht was pegged to the US, a practice that was common among the Asian economies. Its real estate sector had pushed the nation’s foreign debt beyond sustainable limits and speculative capital outflows, motivated by the fear of losses if the currency fell in value put pressure on the exchange rate.

In the face of these pressures, the central bank was unable to maintain the peg as it ran short of the required foreign currency reserves. Once the government floated the baht on July 2, 1997, its value fell by more than 50 per cent as international investors dumped it on the foreign exchange rate and created a massive excess supply.

The collapse of the currency effectively rendered the nation bankrupt, given the large volumes of foreign-currency denominated debt held by the private sector. There was a significant fall in the local shares market and several major financial institutions were bankrupted.

The development exposed the dangers of maintaining currency pegs, which required central banks to have sufficient foreign currency reserves to maintain the agreed parities. This made all currencies in the region susceptible to speculative attacks.

While the structure of the Thai economy was very different economy to the Tigers in the East, speculators considered that all currencies were in danger. This belief became a self-fulfilling prophecy and By August 1997, speculative attacks on the currencies of Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines led to declines in their exchange rates.

The crisis spread in September to Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan and, in November 1997, the capital outflow from South Korea forced it to devalue.

[TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK]

27.8 Capital controls

[UNCHANGED TEXT ON CAPITAL CONTROLS]

Conclusion

DEFINITELY FINISHING THIS CHAPTER NEXT WEEK.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

TYPO:

Second, the US Federal Reserve increased interest rates which pushed up the value of the US _____ and placed strain on the currencies which were pegged to it.

Bill –

Were the speculators right? Were those currencies genuinely overvalued? How do you think the ringgit would have done had the government not repegged it?