It is a public holiday in Australia today celebrating our national day - the day…

The income-expenditure relationship in macroeconomics – graphic treatment

We have been doing a lot of work developing the MOOC at the University of Newcastle which will also mark the first – MMTed material. We will follow up the MOOC with more detailed learning options in subsequent months. Tomorrow, we will be filming some more material for the MOOC and I think you will enjoy what we have planned when the MOOC begins on March 3, 2021. As part of the planning I have been thinking of simplified frameworks for teaching rather complicated concepts and relationships. Here is an example of that sort of thinking.

MOOC Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century

Over the last several months by way of advancing Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) education initiatives, we have been involved in development a MOOC that will be launched in March 2021.

I am working with – NewcastleX – which is my university’s digital team to create the course material which will be available all around the world for free.

Anyone can enrol and participate and the material is suitable for anyone who is keen to learn new things and discuss these things with others of a like mind.

That is the philosophy of a MOOC.

The course – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century – will start on March 3, 2021 and you can get all the enrolment details (it is free) from the link.

This will mark the first stage of the – MMTed project – that I have been trying to get off the ground for a while now.

We have been hampered by lack of funds to date, but the partnership with the University on this MOOC has really been a massive first step. The digital learning team at the University is first-class and have really helped me understand how these new platforms work.

Understanding the importance of fiscal deficits

What follows is a teaching device I use in introductory programs on macroeconomics which allow students to understand the basic rule of macroeconomics – spending equals output equals income, which drives employment.

It helps us understand the concept of equilibrium in macroeconomics and disabuses us of any notion that equilibriums is equivalent to ‘market clearing’ or full employment, which is the way the mainstream economists think of it.

We learn that an equilibrium can persist at very high levels of unemployment indefinitely without some external influence, like a fiscal stimulus entering the picture.

It can also be used as an alternative form of pedagogy (to algebraic derivations) of the sectoral balances and makes the role of fiscal policy very obvious.

Some people prefer this form of elaboration to the more concise algebra.

We also can easily establish the principle that if there is mass (involuntary) unemployment then we know at least one other thing – the fiscal deficit is too small or the surplus too big.

So I thought I would share this exposition with you all on my blog to diversify the way I usually present things.

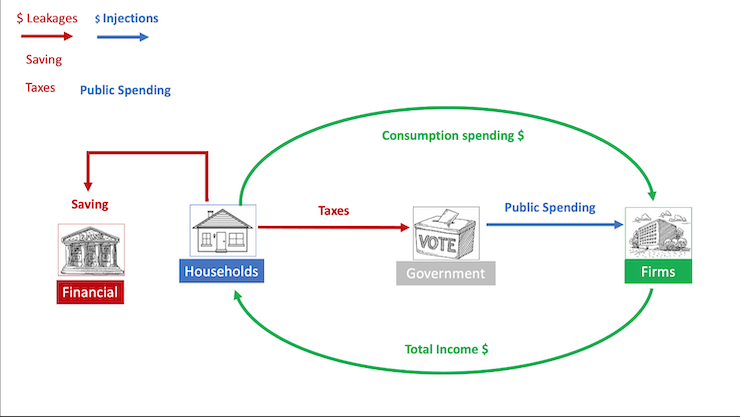

And those who have previously studied economics will identify that this sort of structure is based on the long-standing circular flow exposition, which I tailor to suit my Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective.

So a series of pictures which start from a simple basis and then get increasingly complicated as we introduce more and more real world elements.

Households and Firms

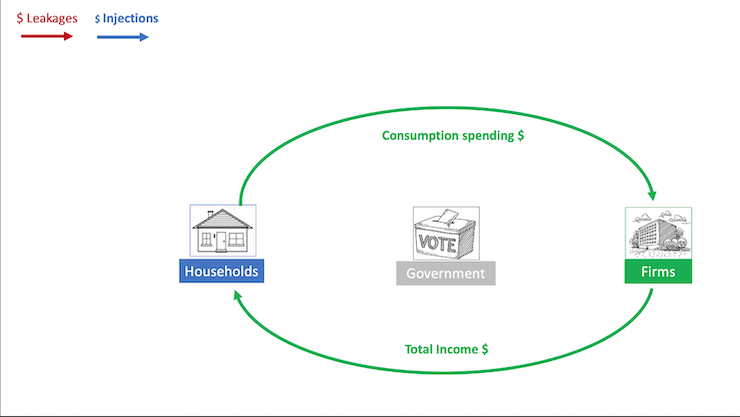

We start with a simple representation of the economy where we have households and firms.

The government is there too but we will abstract from its role at first even though none of this could happen without currency injections from the government.

Throughout this analysis, we assume that prices are stable so that all the dollar flows are effectively in real purchasing power terms.

Business firms form expectations of what total spending in the economy will be and then assemble working capital and workers to produce to that expected sales volume. They price according to their unit cost estimates and their desired markup, the latter which reflects their profit ambitions.

That deployment then pays incomes to the suppliers of productive inputs.

Household consumption expenditure is then driven by total income, which returns revenue to the firms and around we go.

Spending drives output and employment which equals income.

If there are no leakages from this circular flow and/or external shocks, then the system would be stable and persist indefinitely.

This is what we call a macroeconomic equilibrium state.

Now there is no presumption that this steady-state will coincide with full employment. It might but it is highly unlikely.

And it was this sort of underemployment equilibrium state that Keynes said justified government stimulus to break it up and push the economy to a higher employment state.

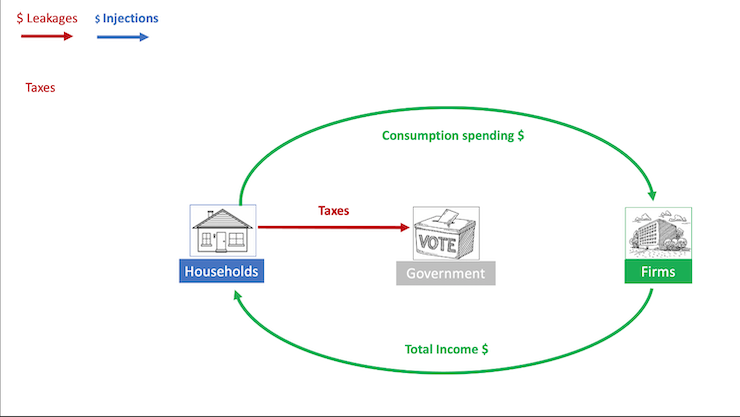

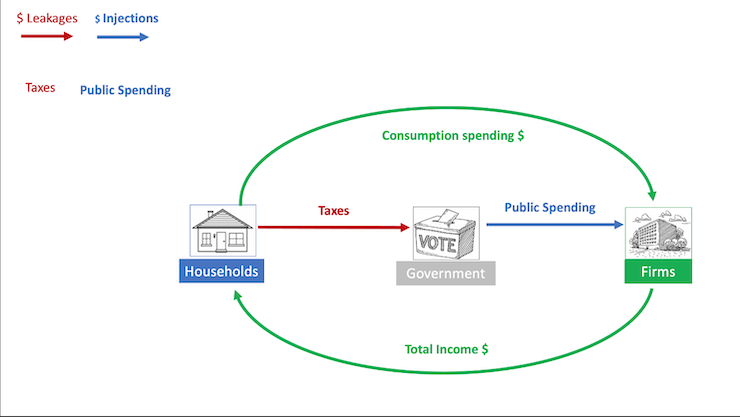

Tax leakage

Now what happens if we disturb this state by forcing the non-government sector to pay taxes?

In this example, I am abstracting from corporate taxes (and, as you will see social transfers). Their inclusion doesn’t fundamentally alter the story.

Now if that is all the happened – the taxes draining income out of the non-government sector into the government sector then total income flow becomes a disposable income flow and the consumption spending flow would be less.

As a result, firms would respond to the rising unsold inventories and produce less and lay off workers.

So, in a modern monetary system, the imposition of taxes creates the condition where idle resources increase.

To return the economy to the previous equilibrium (restore the level of GDP and national income), the flow of government spending must at least offset the leakage of purchasing power from the tax drain.

Now, we stated before that the original steady state was probably one where involuntary unemployment existed even though firms’ expectations of sales volumes were being continually met.

So even if the government spending injection offset the loss of consumption spending arising from the tax leakage, the economy would still be at below full employment.

In other words, the only way the economy could move towards full employment in this context (noting that households consume 100 per cent of their disposable income), would be for the government deficit to rise.

The excess government spending over taxes (G > T) would stimulate sales and firms would hire more workers and pay out higher incomes, which would then lead to higher tax revenue (if the tax system was linked to incomes) and higher household consumption expenditure.

This adjustment process – to the increase in government spending into deficit is what is called the expenditure multiplier.

Please read my blog post – Spending multipliers (December 28, 2009)- for more discussion on this point.

So under these conditions it is easy to understand that if there is involuntary unemployment (which means that people would take a job at the current wages if one was offered to them), then we know the fiscal deficit is too low.

You may also wonder how this new deficit spending state would restore equilibrium.

Well in these simplified conditions, the initial government spending impulse (into deficit) would stimulate rising income, rising taxation, rising consumption, with each additional induced increase in taxes and consumption spending being smaller than the last (because of the tax leakage at each step).

A new equilibrium would be reached at a higher income level once the change in tax revenue reached zero and total tax revenue was equal to the new level of government spending – thus wiping out the fiscal deficit.

If households consume all their income (as is being assumed at present) then equilibrium can only occur with the government in balance once a tax leakage is created.

The general rule is that equilibrium occurs when the leakages equal the injections.

This doesn’t mean we support fiscal balance. It is just a condition that would have to apply in this highly simplified case.

So let’s complicate it further.

Saving leakage

Now what happens if we are at a new equilibrium and households decide to save a proportion of their disposable income.

So now the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), which is the proportion of every extra dollar of disposable income receive that households consume is less than one.

That means that the marginal propensity to save (MPS) would be equal to 1 minus MPC.

We now have an additional leakage from the income-expenditure stream, which if nothing else happened would reduce output, income, employment and subsequent consumption expenditure.

So higher saving alone will create unemployment in the non-government sector at the current settings.

With the current institutional complexity, the unemployment could be mopped up if government went into deficit (remember under our simplistic conditions the government was in balance previously).

The rising fiscal deficit could offset the loss of household consumption expenditure arising from the saving leakage.

The adjustment process would see national income rising again (as government spending exceeded the current tax revenue), tax revenue rising, household consumption spending and saving flows rising and would reach a new national income level when the sum of the leakages (taxes plus saving) equal the injection of government spending (into deficit).

So now there is no requirement that the fiscal position remain in balance. It has to be in deficit under these conditions to maintain full employment when household saving propensity is greater than zero.

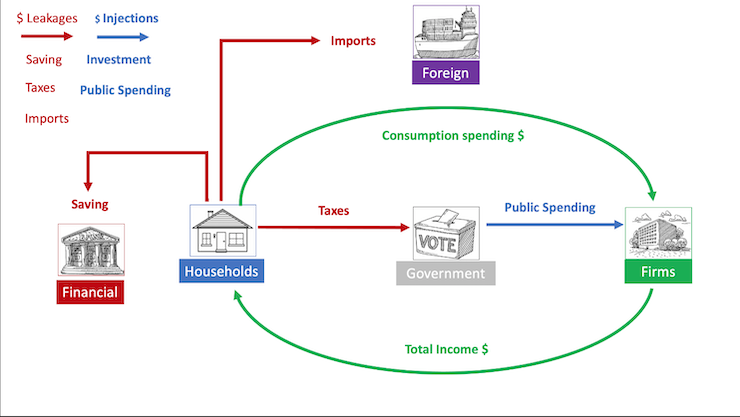

Introduce imports

Now we add the foreign sector and recognise that the domestic economy spends some of its income each period on goods and services produced abroad – imports.

The flow of spending on imports constitutes an additional leakage from the leakage from the income-expenditure stream, which if no other intervention occurred would reduce output, income, employment and subsequent consumption expenditure.

Leakages reduce spending on domestic production and reduce national income.

Injections add to spending on domestic production and increase national income.

Again, the loss of national income could be avoided if the fiscal deficit rose again to counter the leakages of imports.

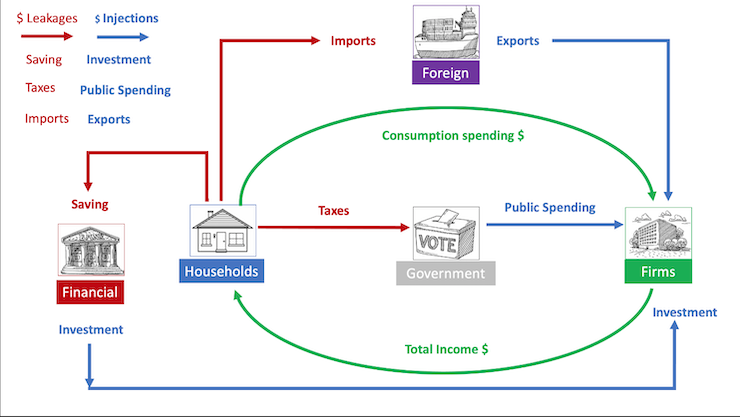

Introduce Business Investment and Exports

In this framework, there are two additional injections that can offset the saving, tax, and import leakages – business investment and exports expenditure from the rest of the world.

At the current fiscal deficit, the spending flow injections from investment and exports would drive the economy beyond the full employment income level.

In fact the government could cut its net spending as these other spending injections entered the expenditure stream in order to maintain the output level at full employment.

There are, of course, many different scenarios that we could play with in this framework.

One could construct a situation where export revenue is so strong relative to the import leakage that the economy could sustain full employment with the government in fiscal surplus.

The condition for equilibrium is that the leakages have to equal the injections.

So:

Saving + Taxes + Imports = Investment + Government + Exports

That condition will hold in equilibrium, and, given that in this simple model the three leakages are also functions of income (they rise when national income rises according to the propensities to save and import and the tax rate), there is a unique sum of injections that are required to offset the sum of the leakages that would be forthcoming at a full employment level of national income (GDP).

That doesn’t necessarily mean a government deficit is required.

But it does mean that if the sum of business investment and exports, given current government spending is not sufficient to equal what the the sum of the leakages that would be forthcoming at a full employment level of national income (GDP), then the only way the economy can reach full employment is if government spending rises.

So the equilibrium condition will deliver a stable level of output, but that, however, does not guarantee full employment.

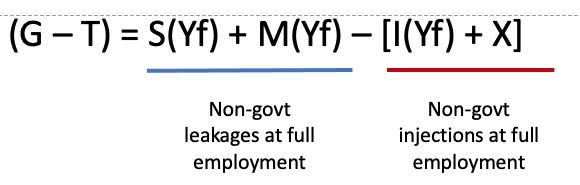

Accordingly, to sustain full employment the condition for stable national income above can be re-written more specifically in this way:

G = Government spending

T = Tax revenue

S = Saving flow

M = Import spending

I = Investment spending

X = Export spending

The Yf qualifier refers to the value of the flow in question at full employment given that the S, T and M flows will be higher at full employment than if the economy is in recession.

If the non-government drains > the injections which would occur at full employment, then for national income to remain stable, there has to be a fiscal deficit (G – T) sufficient to offset that gap in aggregate demand.

Conclusion

We eventually reached the sectoral balance relationship.

But the graphical exposition might provide further understandings that evade those who dislike the algebraic exposition.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Prof. Mitchell,

Respectfully, I would like to make a suggestion. I am sure that for you it’s obvious that those financial flows between Households and Firms have counterparts in physical flows: for example, from Households flows of labour depart and arrive into Firms, while from Firms depart flows of physical goods and services, which arrive into Households. People work for firms, so as to buy stuff they need and their employers sell.

I have observed that that seems less than obvious for beginners and even some more advanced students.

To make that even more evident, I would also suggest explicit references to physical flows within the text. Goods and services are only mentioned once, when imports are introduced.

Cheers.

Dear Bill,

In the spirit of constructive criticism:

1. Some of the colours in your diagram are doing double duty – red for leakage flow and financial sector, blue for injection flow and household sector. For me it would be simpler to distinguish these with different colours, e.g. primary for flows, pastel for sectors?

2. Your equation has unbalanced brackets.

3. You probably disagree with this view, and it certainly is not part of the standard sectorial model, but in the diagram with imports but no exports, you have a foreign sector, while in reality the currency (almost) never leaves the country. This seems to be a common misconception, that is reinforced by the diagram as it currently stands.

I forgot to add that, of course, comment 3 applies to a country with a fiat currency.

Dear dnm (at 2021/02/16 at 6:09 pm)

Thanks for the comments.

1. The colours seem okay to me – the induced flows are green, the leakages are red and the injections are blue. There is no difference between the financial flows as you call them and the expenditure flows for the purposes of this exercise – they either add to spending or breach the relationship between spending and income.

2. Fixed the equation – Thanks.

3. It doesn’t matter that the currency remains in local banks when imports are bought. The point is that that the flow of income is not recycled back into local production. That is the point that matters. Where the revenue from the imports (via a local distributor) is held is irrelevant for this exercise. The diagram is about income-expenditure relationships (flows) not about the stocks of financial assets in whatever currency.

Best wishes

bill

With my slow 78 year old brain this will be a huge help. I say will be because I will still need to read and re-read. I wonder if a further aid to those slow-coaches like me (if such exist)

, animation of this series of diagrams might be of yet further benefit? Feeling guilty to keep asking for yet more!!!

Dear Bill,

The word “abstract” in the context of “The government is there too but we will abstract from its role at first . . .” is not plain in its meaning and might be better stated as “exclude” or “omit” for ease of understanding, as I see it. And similarly here: “In this example, I am abstracting from corporate taxes (and, as you will see social transfers). Their inclusion doesn’t fundamentally alter the story.”

As a matter of framing, the terminology used in the flow diagrams may be improved if “Firms” be renamed “Business” or “Private Business”. With the latter term it is readily understandable that “Public Business” such as public service employment is excluded from the depicted model.

I hope this has been helpful.

Fred

Personally Stephanie’s bath tubs and water flows works well with flows stocks and leaks. Real simple put the labels G, X etc simple visualisation. Overflow the bath and inflation, drain the bath and bankrupt, float all the boats full employment.

Dear Kento (at 2021/02/16 at 8;27 pm)

The problem is that the bath tub example is incorrect and confuses stocks and flows. GDP is a flow not a stock. The bathtub example make it out to be a stock.

Please read this for clarification

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=44232

best wishes

bill

When differentiating using colour alone in infographics, please be aware that one in twelve males and one in twenty females are colour blind.

Differentiation using varying line widths, dotted and dashed lines, varying patterned fills in graph bars, etc. in addition to simply using colour, can really help those who live with this very common disability.

With respect to the equation, the functions (in terms of the equations), S, M, and I, are specified but the argument to the functions, Yf, is not. It needs to be specified as well along with everything else. It shouldn’t be assumed that the reader will know from reading the text or from anywhere else or remember it. A standard reaction is: What does that refer to (mean) again?

Is the principal goal of MMT, along with all other disciplines, to fine tune the economy or to make human life in all of its aspects compatible with planetary constraints? “Now there is no presumption that this steady-state will coincide with full employment. It might but it is highly unlikely.” Understood, but full employment will mean little, and even then not for long, if the elephant in the room is not directly addressed NOW. Here’s where we are, in a pressing, terrifying existential predicament, which makes the fine-tuning of capitalism trivial at best, part of the problem at worst.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2021/02/15/can-we-exit-this-road-to-ruin/

Dear Larry (at 2021/02/16 at 9:31 pm)

The Yf is specified specifically with the other variables – The text reads “The Yf qualifier refers to the value of the flow in question at full employment given that the S, T and M flows will be higher at full employment than if the economy is in recession.”

I guess you skimmed that part.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill I have left a donation for the course. I will look forward to undertaking the study and work involved. I am a slow learner, but still enthusiastic to learn new things Thank you for all your hard work.

I’m not sure why the blue arrow for public spending only goes to firms and there is not also another line to households

Dear Prof. Mitchell

Regarding Larry’s point about the Yf qualifier and to avoid future confusion I’d propose S, M, and I to be written with a subscript instead of in parentheses. I think it makes more sense because the equation is an identity and doesn’t include any functions.

@Newton: “Is the principal goal of MMT, along with all other disciplines, to fine tune the economy or to make human life in all of its aspects compatible with planetary constraints?”

Isn’t the principal goal of a good government ensuring that every citizen has sufficient of the basic necessities of food and shelter from the elements – within ‘planetary constraints’?

MMT shows that the government of a monetarily sovereign state has the power to control the allocation of resources – and not just in wartime. There is plenty of scope for markets to decide how less important resources are allocated. The question ‘Why are people starving and living on the street in a rich country like ours?’ should be answered.

Bill, you are right. I missed it. I don’t know how. Sorry for the confusion.

Totally agree, Carol. Food and shelter, all the basic necessities, are essential for the flourishing of human life. But our providing of these for ourselves, in large part, I believe best, through democratic government guided by MMT, must also allow other living things to flourish. We and they, of course, are all part of that increasingly fragile thing we call “the environment.”

Yes, Newton, food provision works well through the markets, with regulation, but housing does not. Government must intervene in the land market, just as the labour market (JG). Then decent wages and benefits for those who cannot work or have special needs, is the basis of good government.

Your work is brilliant and much appreciated. However, I have to wonder about the value or meaning of full employment. I assume you will deal with the leakages from the firms in another post, but what if full employment were a myth. How would that affect your equation?

Dear Ron Vormald (at 2021/02/18 at 3:19 pm)

Thanks for your comments and appreciation.

But what exactly is ‘mythical’ about the 877,600 persons in Australia who are currently without work and desire to work and are available to start work today. And what about the 1,125.7 thousand underemployed workers in Australia who, on average, desire 15 extra hours of work a week.

Repeat for almost every country in the world.

Where is the myth?

best wishes

bill

Well Bill, perhaps they are unemployed because they are demanding excessive real wages that cause the capitalist class to refuse to invest their money. Been told that on your quiz answers at least. Their excessive wage demands could be causing the massive underemployment you describe.

But more likely is the general MMT story about insufficient government spending or excessive taxation leaving potentially productive people without productive employment.

All unemployment is voluntary (Patrick Minford, Thatcher go-to – still around). Just need to lower your offer till an employer can afford you.

Yeah Carol but we know that all unemployment is not voluntary and that Thatcher was wrong more than occasionally. Lowering your wage demand is not a guaranteed path to employment even as an individual let alone cutting wages in general and expecting increases in employment to result from that.

But Bill Mitchell has developed the best understanding of mass unemployment that I have ever encountered yet sometimes discounts it for reasons that are not apparent to me. And so sometimes I will be a pain in the ass about telling him he is right. Hopefully he can handle someone who argues he is correct after dealing with so so many people who have said he is wrong for so many wrong reasons. I suspect he can.

Carol,

“All unemployment is voluntary”

Imagine you’re an employer. The bank has just told you to zero the overdraft. There has been a stock market collapse. Overleveraged investors are liquidating like mad. The credit markets are frozen and there is a liquidity shortage. Hence your bank is pulling in every cent it can. Your sales have collapsed. You are liquidating stocks to get cash and there are a bunch of people (employees) who expecting to be paid at the end of the week. You have to let go of as many as you can without destroying the long term prospects of the business. No matter what wage they are willing to work for, you don’t want them.

This is involuntary unemployment and it is very real.

(Perhaps you’re just being sarcastic?)

Henry, I think Carol was being sarcastic and ripping on some of the lies that people like Margaret Thatcher dealt in.

Not enough British on here. We invented sarcasm.

Thumbs up for Mr Shigemitsu’s comment.

Also, if we are serious about making mainstream econs obsolete, it might pay to not use the word “equilibrium” for the balances in such models. Equilibrium in economics is a mainstream term, a badly used term. Just use the word “balance”. The analogy is with mass-energy and charge conservation in physics: both are conserved (in “balance”) in either equilibrium or highly non-equilibrium systems.

Every model drawn by Bill could be describing flow balances in a highly out-of-equilibrium economy w.r.t. wealth distribution and resource consumption.

@’Carol Wilcox’ except sarcasm comes from the Greek sarkasmos “a sneer, jest, taunt, mockery.” So what you’re saying is the British really invented language and cultural appropriation I guess? Or did they even steal that! 😉

Brian Romanchuk (bondeconomics.com) wrote an article, titled “The Great Vacation: Recessions In DSGE Models (Part I)”, and pointed out that “equilibrium” is an obsolete term, since it’s not what the mathematics of current DSGE models actually leads to.

In one of his recent critiques of MMT, Thomas Palley used the term “steady state”. Don’t know whether that’s the new term of art, or Palley just wanted some variety in his wording. (The statement was that Palley himself was most interested in return to the steady state after a shock; there’s no reason to doubt that he really is most interested in that, assuming there is that kind of return.)

Hello.

I am Japanese.

I am writing by machine translation.

In your text, you have the following formula:

Saving + Taxes + Imports = Investment + Government + Exports

Does “investment” on the right mean investment by bank borrowing?

Or does it mean investing by using the “savings” on the left?

Dear kyunkyun (at 2021/02/22 at 6:12 pm)

Investment is the spending by business firms on productive capacity – machines, technology, equipment etc.

How it is funded is a separate issue.

best wishes

bill

Thank you Bill.

There is the following logic about the case where savings are used for investment.

This logic is that “Production using savings increases production without increasing income. Therefore, production using savings creates a gap between production and income”.

Let me hear what you think about this logic.

The following is a quote of this logic.

https://www.michaeljournal.org/articles/social-credit/item/douglas-s-three-propositions

– And what is Douglas’s second proposition?

“Why finance production this way, with new credits, and not with savings? Because savings come from money that has been distributed in relation with a realized production. Now all this money has gone into the cost price of the realized production. If this money is not used to buy production, the gap between the means of payment and prices will increase.

One can put forward that the savings used to finance a new production flow, through investments or otherwise, comes back into circulation as purchasing power. It is true, but it is as expenses made by the producer, therefore creating a new price. Now, the same amount of money cannot serve to pay, at the same time, the corresponding price of the former production and the corresponding price of the new production.

Each time saved money thus comes back to the consumers, it is by creating a new price, without having paid a former price left without corresponding purchasing power when this money becomes savings.

Let us clarify this point by an example:

Here is a worker who draws a monthly wage of $300. On this amount, he draws out $50.00 to buy shares in an enterprise that is building a new factory.

The $300 in wages is most certainly listed in the prices of the goods for which the worker worked; but in front of this price of $300, there is only $250 left in purchasing power.

The building of the factory will put back the $50 as purchasing power through the wages distributed to the construction workers. But the goods which will come out of the new factory will have to include the $50 in their prices. The $50, which has become again purchasing power, will most certainly not be able to pay, at the same time, the $50 price of the former production and the $50 price of the new production.

This does not mean that the saver is doing the wrong thing by investing his money in the expansion of production. He is perfectly free to do what he pleases with a money that belongs to him. But the subtraction to the global purchasing power, made by savings, must be compensated in some way through an equivalent amount of money coming into the consumers’ hands (through the social dividend, for example, or through an increase in the compensated discount). Once this is done, the effect on the purchasing power will be the same as if the production had been financed directly through new credits, since these new credits replace the savings diverted from the purchasing power.

The present system does not make this compensation. It insists on financing through savings, without worrying about the cut made into the purchasing power. It is not the only cause, but one of the causes, of the gap between the consumers’ means of payment and the prices of goods.”