It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

External economy considerations – Part 8

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to publish the text sometime in 2013. Our (very incomplete) textbook homepage – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice – has draft chapters and contents etc in varying states of completion. Comments are always welcome. Note also that the text I post here is not intended to be a blog-style narrative but constitutes the drafting work I am doing – that is, the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change as the drafting process evolves.

Chapter 21 Policy in an Open Economy: Exchange Rates, Balance of Payments, and Competitiveness

This material updates the work already done on Chapter 21 that appeared in the following blogs:

- External economy considerations – Part 1

- External economy considerations – Part 2

- External economy considerations – Part 3

- External economy considerations – Part 4

- External economy considerations – Part 5

- External economy considerations – Part 6

- External economy considerations – Part 7

Today, I am just continuing filling in the gaps in the Chapter.

21.7 Currency crises

[CONTINUING THIS SECTION FROM LAST WEEK]

The 1994 Mexican Peso Crisis

[MATERIAL HERE INTRODUCING THE CRISIS LAST WEEK]

The decision by the Mexican government to float the peso was forced on it because it ran out of the foreign reserves that were necessary for the central bank to maintain the peg against the US dollar as speculators were selling out the currency and driving its price down in world markets.

The short-term consequences of the depreciation were severe. The severity was linked, in part, to the government’s tardiness in making the decision. The events occurred in an presidential election year and both the instability associated with the bitterly fought campaign (including the assassination of one of the leading candidates) and the reluctance of the incumbent who wanted to avoid the stigma of devaluation meant that the peg remained in place despite massive outflows of funds.

The peg signified a sort of status for the Mexican government who had instilled a sense of confidence in the Mexican economy by becoming a member of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and entering the NAFTA in early 1994.

They also liberalised credit and privatised the banking system, which exposed the nation to rapid capital inflow without a commensurate increase in the ability of its financial institutions to handle the risks involved in international finance.

Once they were forced to float the response of the international markets was extreme. The investors (both foreign and Mexican), who had previously held out Mexico as the exemplar for Latin America to follow, sold off pesos in astonishing proportions in a space of a few days (December 20-22, 1993).

Given the desire to maintain the peg, the government left itself with two undesirable options as the capital outflow accelerated and the central bank foreign reserves rapidly declined.

First, they could have hiked interest rates to encourage investors to leave their funds in Mexico. The problem was that the required interest rate increases would have been so large that tjey would have plunged the economy into a major recession.

Second, they could have broadened the bands in which they allowed the peg to crawl which would have improved the current account a little and perhaps offset some of the mania that was creeping into foreign exchange markets about the likely depreciation of the peso.

But the consequences of that option would have inflated the debt servicing payments on foreign debt held by Mexican companies and the Government with the inevitable consequence of insolvency.

Eventually, a combination of IMF and US government assistance stabilised the financial system and placated the international investment community, which realised that the economic fundamentals were unchanged and had not justified the massive over-reaction.

In summary, the Mexican peso crisis teaches us some important macroeconomic policy lessons.

First, while a floating exchange rate may expose an economy to imported inflation in times of depreciation, the advantages in being able to stabilise domestic output and employment are significant. A nation, which pegs its currency, loses control of monetary policy and forces fiscal policy to play a passive role that becomes destructive when the currency depreciates significantly.

Second, while it is clear that a currency-issuing government should not issue public debt, it is imperative that any liabilities it does issue are denominated in its own currency and assume no foreign exchange risk by way of indexing or insurance arrangements.

The South East Asian Debt Crisis 1997

The last major currency crisis in the 1990s began in 1997 in the South East Asian nations of Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Indonesia and, later, spread to the industrialised East Asian nation of South Korea.

In the two decades leading up to the crisis, the SE Asian nations had attracted large capital inflows and grew rapidly. They were considered by the IMF to be models of sustainable development.

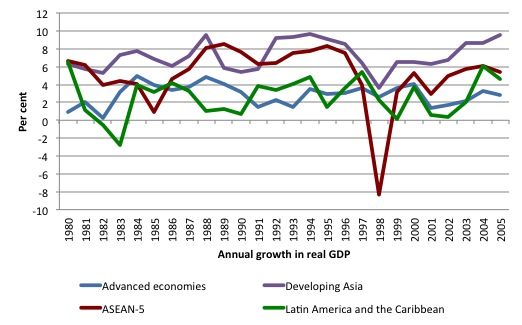

Figure 21.6 compares the annual real GDP growth rates for several blocks of nations including the ASEAN-5, which is comprises: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. You can consult the IMF World Economic Outlook database for full descriptions of the other groupings.

Figure 21.6 Real GDP growth in South East Asia, 1980-2005, per cent per annum

[TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK]

27.8 Capital controls

[UNCHANGED TEXT ON CAPITAL CONTROLS]

Conclusion

DEFINITELY FINISHING THIS CHAPTER NEXT WEEK.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments