It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

External economy considerations – Part 4

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to publish the text sometime in 2013. Our (very incomplete) textbook homepage – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice – has draft chapters and contents etc in varying states of completion. Comments are always welcome. Note also that the text I post here is not intended to be a blog-style narrative but constitutes the drafting work I am doing – that is, the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change as the drafting process evolves.

Chapter 21 Policy in an Open Economy: Exchange Rates, Balance of Payments, and Competitiveness

This material updates the work already done on Chapter 21 that appeared in the following blogs:

- External economy considerations – Part 1

- External economy considerations – Part 2

- External economy considerations – Part 3

The material was previously in Chapter 15 but some re-arrangement of the sequence of the pedagogy has resulted in this discussion now becoming Chapter 21.

The earlier draft had some gaps and some sections to complete which is what I am doing today. The sections I am working on today are not in any particular sequential order.

21.2 The Balance of Payments

Residents (households, firms, and governments) of every nation conduct economic transactions with residents of other nations and the record of all these transactions is recorded in the international accounts for each nation. The international accounts are made up of a number of component accounts (IMF, 2011:7):

- The international investment position (IIP) which “shows at a point in time the value of: financial assets of residents of an economy that are claims on nonresidents or are gold bul- lion held as reserve assets; and the liabilities of residents of an economy to nonresidents” (IMF, 2011:7).

- The balance of payments which is “a statistical statement that summarizes transactions between residents and nonresidents during a period. It consists of the goods and services account, the primary income account, the secondary income account, the capital account, and the financial account”(IMF, 2011:7).

- All “other changes in financial assets and liabilities accounts” (valuation changes etc) (IMF, 2011:7).

The Balance of Payments and related accounts are compiled by national statistical agencies (such as the UK OFfice of National Statistics, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis) using international standard set down in the International Monetary Fund’s <Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6) (IMF, 2011), augmented by the System of National Accounts 2008 (2008 SNA). While there are variations in terminology used by different nations the principles are universal.

The IMF Manual is seen as the “standard framework for statistics on the transactions and positions between an economy and the rest of the world” (IMF, 2011: 1).

The IMF define the Balance of Payments as:

… a statistical statement that summarizes transactions between residents and nonresidents during a period. It consists of the goods and services account, the primary income account, the secondary income account, the capital account, and the financial account.

The differentiating feature of these different accounts relates to “the nature of the economic resources provided and received” by the nation (IMF, 2011: 9).

Like any accounting framework, the Balance of Payments is based on a double-entry debt and credit system of record. Every transaction that is recorded has two equal and offsetting entries, each of which corresponds to the inflow and outflow of funds.

Credit entries consist of transactions where foreign residents make payments to local residents. Examples include exports of goods and services, income recievable from investments abroad, reductions in external assets, or increases in external liability.

Debit entries consist of transactions where local residents have to make payments to foreign residents. Examples include imports of goods and services, income payable, increases in assets, or a decrease in liabilities.

|

Balance of Payment examples Example 1: Export of goods and services An Australian resident sells $1000 worth of goods to a resident in the US. The Balance of Payments in Australia will record:

Example 2: Australian resident borrows from a US bank An Australian resident takes out a loan for $1000 from a US bank. The Balance of Payments in Australia will record:

|

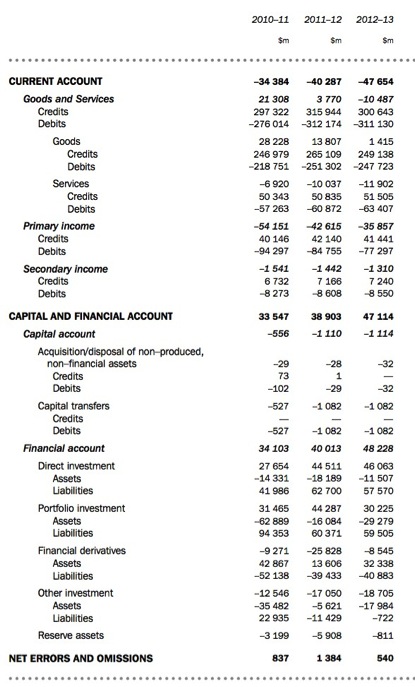

Table 21.1 shows how the Australian Bureau of Statistics presents the Balance of Payments data for Australia. Observe the heading structure: Current Account and Capital and Financial Account being the major sub-accounts of the Balance of Payments. Then within each of the sub-accounts are a number of other sub-headings which record different elements of the transactions between Australia and the rest of the world.

We will briefly discuss the Current Account and the Capital and Financial Account.

Table 21.1 Australian Balance of Payments, various years, current prices

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cat No. 5302. Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, June, 2013.

The Current Account

The current account records all current transactions between a nation’s residents and non-residents in goods and services, primary income and secondary income.

The goods and services or balance of trade records “transactions in items that are outcomes of production activities” (IMF, 2011: 149) and reflect exchanges between the local economy and the rest of the world. The data is typically collected from information collected from exporters and importers by the nation’s customs department.

Exports and imports of goods relate to movable or tangible goods, while services are considered to be all products other than tangible goods. Services include items such as banking and insurance, transport, and export education. While items bought by tourists while on holiday may be tangible, all such expenditure is recorded as services under the IMF conventions used.

Primary income (IMF, 2011: 183):

… represents the return that accrues to institutional units for their contribution to the production process or for the provision of financial assets and renting natural resources to other institutional units.

There are two categories of primary income accounted for:

- Income that is associated with the production process, for example, wages paid, taxes and subsidies on production. If a resident is paid for labour by a non-resident then primary income is deemed to have been earned and vice versa.

- Income that is associated with the ownership of financial assets, for example, dividends and interest.

These flows are accounted for in the primary account if they are current. You will appreciate that they impact on the measure of national income in the national accounts.

The secondary income account relates to current transfers between residents and non-residents which do not add to national income, but rather, involve redistributions of income between nations. There is nothing of economic value that is exchanged in return for a secondary income transfer.

Some of the typical secondary income account transactions include personal transfers (remittances to or from overseas), charitable contributions, social benefits (such as, pension payments to or from abroad), and current taxes on income and wealth.

Economists are often focused on the current account because of the transactions it records are of direct relevance to the determination of national income. Our earlier discussions about the sectoral balances and the income-expenditure determination all explicitly considered the current account of the balance of payments.

Exports (injections) and imports (drains) are key components of aggregate demand.

The Capital Account and Financial Account

While the current account of a national tends to focus on transactions with the rest of the world, which impact on the measurement of national output and income, the capital account capital account is the financial side of these transactions.

What would happen if a nation exported more than they imported? Ignoring the primary and secondary accounts for the moment, the net outflow of real goods and services would be accompanied by accumulating financial claims against the rest of the world. This is because the demand for the nation’s currency to meet the payments necessary for the exports would exceed the supply of the currency to the foreign exchange market to facilitate the import expenditure.

How might this imbalance be resolved? There are a number of ways possible. A most obvious solution would be for foreigners to borrow funds from the domestic residents. This would lead to a net accumulation of foreign claims (assets) held by residents. This item would be recorded in the capital account as a debit because it enhances the capacity of non-residents to make transactions in the local economy.

Another solution would be for non-residents to draw down local bank balances, which means that net liabilities to non-residents would decline.

The capital account thus records the “credit and debit entries for nonproduced nonfinancial assets and capital transfers between residents and nonresidents. It records acquisitions and disposals of nonproduced nonfinancial assets, such as land sold to embassies and sales of leases and licenses, as well as capital transfers, that is, the provision of resources for capital purposes by one party without anything of economic value being supplied as a direct return to that party.” (IMF, 2011: 9).

The financial account is a balancing account, recording the “net acquisition and disposal of financial assets and liabilities” (IMF, 2011: 10).

It we add the current and capital account together then the result “represents the net lending (surplus) or net borrowing (deficit) by the economy with the rest of the world” (IMF, 2011: 10).

This difference is the net balance of the financial account, which details the funding of the net lending or borrowing from non-residents.

Reference

International Monetary Fund (2011) Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6), Washington – Available from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/pdf/bpm6.pdf (BPM6).

Conclusion

I WILL FINISH THIS CHAPTER NEXT WEEK BY FOCUSING ON CAPITAL FLOWS, THE OPTIONS FACING A NATION WITH SPECULATIVE ATTACKS ON ITS CURRENCY, THE ISSUE OF CAPITAL CONTROLS etc

I WILL ALSO CONSIDER THE DEBATE AS TO WHETHER THE CURRENT ACCOUNT DRIVES THE CAPITAL ACCOUNT OR VICE-VERSA

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Is it worth discussing the effect of the denomination that national accounts are in. For example when an Australian sells a real item to the US, then there is a bilateral effect on both the national accounts.

However the Australian national accounts are in $A and the US national accounts are in $US, and that means that the same transaction will appear different in each of those places.

That revaluation to the national unit of account can distort the view of the underlying currency systems and their reach beyond the national borders (and probably in some countries, not as far as the national border).

Something to make students aware of I feel.

I was about to make the same comment as Neil, but I’ll just say that I concur. It would be better either to use two currencies with different symbols or distinguish the examples by A$ and US$.