I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The day the Australian media failed the public, again

For those who don’t know about cricket, it is good to get a high score in each of the innings. Just like baseball. An innings score of 350 runs in Cricket would be respectable. So imagine the headlines – Big problem, team only scores 130 runs in final innings! The whole cricket world then gets itself in a lather about this with experts blabbing on national TV about only 130 runs. As an after thought, the news bulletin also announced – “and team pulls off a thrilling victory”. Imagine, some bean counter expert coming out in the middle of a game of football and telling the teams that the game is being called off because the budget for goals had been exhausted. The two points – context with respect to meaning and aims and where does the unit of account come from – have been sadly lost in the current economic debate. Even journalists who know better have done a great disservice to the Australian public today by choosing to present an uncritical version of a report that is at best incompetent but also much worse than that. This morning Australians have been bombarded via TV, radio and the printed media with economists, appearing seriously self-important but, at the end of it all, all they are doing is making stuff up and are probably too stupid to know otherwise.

First, there was the news over the weekend that the Federal Government would not succeed in meeting the budgetary estimates provided in its – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook – which in December 2012 downgraded the growth estimates from the May 2012 Budget and led, ultimately, to the Treasurer finally announcing that they would not be able to achieve a surplus in this year as planned.

In the ABC News Story (April 22, 2013) – Economists predict multi-billion dollar budget deficit – we read that;

the Federal Government will announce a multi-billion dollar deficit when it hands down the budget in three weeks’ time.

And so what? What else did it expect with a slowing economy, partly the result of their own surplus obsession. When they announced (2 years ago) that they were pursuing a surplus in this year it was obviously that it was going to fail. Not many economists said that at the time. The majority of my colleagues were urging them on in their vandalism of the Australian economy.

One commentator who is featured by the media (an ex-Treasury official now consultant) claimed:

The budget’s in trouble, we’re talking multi-billions of dollars. We’re not talking the $20 billion deficit that some people are mentioning

Which is about as meaningless as it gets and deceptive for a public that is not capable of seeing why this is so wrong.

What does that mean to say that in relation to a currency-issuing nation that the budget is in trouble?

Sure, the government’s political statements about the budget will be proven to be foolhardy. In that sense, the government has a problem of credibility.

But when you think about its initial promise – that it would create a surplus at a time when the non-government spending was incapable of driving sufficient economic growth to justify that particular fiscal stance – exemplified a lack of credibility.

This is the problem in all of this. Incompetence and incredulous statements are characterised as being the height of fiscal responsibility and prudence. That is how bad the disjuncture between what the public knows and thinks and what is reality is so wide that the opposite of responsible practice becomes the defining feature of responsibility.

A budget of a currency-issuing government can never be “in trouble” when we think in financial terms, and let’s be clear this whole debate is being conducted about financial parameters.

The budget such a nation can be too small or too large but it can never be trouble. In other words, we need context. Did the cricket team win or lose? That is an essential question to ask to frame in our assessment of how many runs it scored in the match.

The ABC article then referred to the other big economics story today – the realise of a report from the so-called “independent public policy think tank” – the Grattan Institute – Budget pressures on Australian governments.

Apparently the author is “one of Australia’s leading public policy thinkers” (Source). Standards seem to be slipping in the way we assign plaudits these days.

The ABC was totally uncritical in its reporting of this document. Just the terminology – “independent”. The list of financial supporters span – government and private enterprise (for example, BHP). Will these organisations keep funding the institute no matter what it says? I think not, which means they are not strictly independent.

The term in the independent has another deeper meaning beyond writing what funding bodies deem to be acceptable.

The report in question slavishly rehearses the mainstream macroeconomic framework that reflects a particular ideology. It does so in an uncritical manner which means that becomes a tool of dogma. That is, the exemplification of dependence.

The Grattan Institute Report claims that Australia is facing a “decade of massive budget deficits if state and federal governments don’t rein in spending, and increase taxes”. They claim that “by 2023 the combined annual deficit of state and federal governments could balloon to $60 billion”.

Even some elementary arithmetic tells us that if GDP grows by 3 per cent per annum (which is under the government forecasts and below trend) then a $A60 billion deficit will be about 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2023.

In relative terms that is not what I would call “massive”. But then it makes no sense to conclude anything about that figure unless we know what it is supporting in real terms.

The Melbourne Age also chose to beat the story up (as in perpetuate the myth) using the shock headline – Huge deficits loom. The normally reasonable Peter Martin, the chief economics correspondent for the Age let us down with this uncritical article.

These think tanks issue their own press release, but then seem to engage the services (free) of a phalanx of journalists and reporters who then just write up the press release in different words and give it national coverage. It is the same message and comes with zero interrogation of the underlying premises.

And then when some rich character takes over the newspaper and imposes editorial prerogative on it, the journalist scream slogans about the freedom of press. Meanwhile, they spend their time, mostly, acting as mouthpieces for neoliberal economic ideology.

Considering the report (linked above), I would fail a first-year macroeconomics student who produced an argument such as is presented in this report.

On Page 29, the author says:

Australia is no longer at the bottom of the economic cycle. Instead, the economy is probably at or above the average performance that can be expected over the next decade or two. GDP growth is close to its average over the 2000s, inflation is inside the RBA’s target of 2-3 per cent, and unemployment is lower than any recent period outside the boom-years of 2005-2008.

Perhaps the “think tank” is so busy thinking and being independent that it hasn’t had time to look at the data. Let me remind the author:

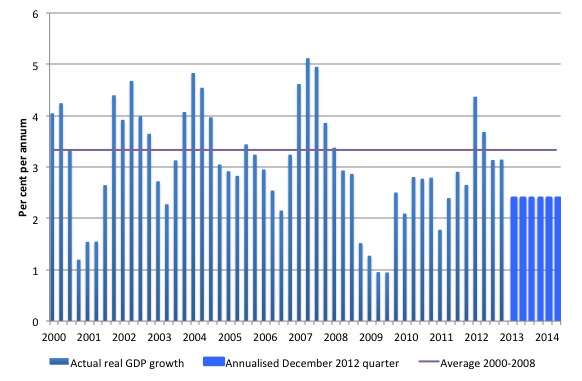

1. Real GDP growth is currently averaging, based on the last quarter, 2.4 per cent per annum and slowing. The average over the growth period from 2000 to 2008 is 3.3 per cent per anum. See the next graph. The brighter bars just extrapolate that average out but in reality the economy is likely to contract some more as the fiscal position becomes tighter and the mining investment slows.

2. The official unemployment rose last month to 5.6 per cent with employment growth being insufficient to keep pace with the underlying population growth. There are 686,900 persons unemployed.

3. There are now 869 thousand persons underemployed – which is 7.1 per cent of the labour force.

4. The participation rate is 65.1 per cent and still substantially down on the most recent peak of 66 per cent (January 2010) when the labour market was gathering pace courtesy of the fiscal stimulus. Hidden unemployment has risen by at least 150,000 workers since the crisis began.

That is not an economy that is performing well. It is not an economy in which the federal government should be running a surplus.

The author was featured all morning on the ABC breakfast TV program this morning (and presumably other media outlets) rehearsing the government’s lie that Australia is growing strongly and close to full employment.

I guess if these cretins just keep saying that and the press do not call them to account we all end up believing the lie to be true.

As noted above the facts do not support the assessment. Real GDP growth is well below the pre-crisis trend and slowing quickly. All the signs are that the massive investment cycle associated with the mining booms is coming to an end, which will push the economy close to zero or into negative growth.

Why didn’t the journalists ask him to justify how full employment becomes at least 14.5 per cent of the willing labour force not having enough work and at least 7 per cent of them no having any work? That would have been a simple question to ask – to probe the author’s underlying biases and premises.

They could have then started on asking the author what he thinks pushing for a budget surplus would do when the household sector is in record debt and trying to save again, the investment boom is easing quickly, and the current account is in deficit.

A budget balance is always the net outcome of government spending and revenue policies interacting with non-government spending and saving decisions.

We say that the budget outcome is endogenous, which means that it is determined by the system, in general, rather than the specific policy decisions taken by government.

In fact, the government cannot realistically target a budget outcome because changes in private spending can thwart any efforts made by the government to achieve that target.

Indeed, we have seen that in the current period, many governments imposing fiscal austerity onto their economies with the intended purpose of reducing the budget deficits, but are, instead, seeing their budget deficits rise (or not falling as quickly as planned) because private spending is not responding in the way they envisaged.

Please read my blog – Keynes would not support fiscal austerity – for more discussion on this point.

I was reading this Report while I was walking up to work this morning at the University of Melbourne (right past the Grattan Institute). I resisted engaging in any indecent gestures.

But I laughed when I got to Chapter 2 – The value of balanced budgets. Footnote two references as its authority Reinhart and Rogoff (This Time it is Different), which has been thoroughly discredited. This is not the Rogoff and Reinhart 2009 AER paper that fell down the Excel black hole of incompetence last week. But the book, which is part of the suite of publications these propagandists have published, has also been highly criticised for its liberal approach to scholarship.

Please read my blog – Watch out for spam! – for more discussion on this point.

The author must have done some last minute editing on this Report because the footnote is appended with a citation of the Herndon et.al 2013 University of Massachusetts paper, which exposed the Excel error (chicanery/incompetence – who knows which?).

It is a pity that the last minute editing didn’t extend to heeding the message of the demolition of R&R. however, that would have required them to delete the whole chapter, which would have been a service to humanity but would have prevented them appearing on TV this morning.

The paper also cites as authority, an IMF paper by Dr Kotlikoff, which is among the worst macroeconomic papers in history. Please read my blogs – Several universities to avoid if you want to study economics and If only the citizens knew what was going on! – for more discussion on this point.

Kotlikoff is the character who gets Op Ed space telling everyone that the US government is bankrupt, despite the fact (which he knows) that it can never become bankrupt unless it chooses to default on its financial obligations for political reasons. The manic Republicans and conservative Democrats might actually push that one day as they continue to lose their grip on reality but even that I doubt. Not the lost grip but then having the intestinal fortitude to actually go that far. Too many of their mates on the corporate welfare system would ring them up quick smart!

Anyway, with a background defined by these sorts of discredited and shameful contributions to the fiscal debate it is little wonder that the Grattan Institute puts out utter garbage.

The author starts with this gem:

Over the economic cycle of boom and bust, balanced budgets are much better than the alternative.

What alternatives? Well apparently “Persistent government deficits incur interest payments, and limit future borrowings”.

What if a nation enjoys a steady current account deficit of around 3 per cent of GDP (that is, domestic residents have somehow induced foreigners to send them more real goods and services than they have to send back and in exchange we give them bits of paper)? What if the private households want to save around 10 per cent of disposable income? What if the private investment ratio is about equivalent to the household saving ratio when converted into proportions of GDP?

Then a balanced budget (peak to peak) is a very poor strategy.

Further, interest payments are income. Income is good. No income is bad.

Further, a deficit today in no way “limit future borrowings”. How does that actually happen? And even if it did, the central bank could take the place of the private bond markets (as we are seeing in many nations at present).

The relevant point is not whether borrowing is possible anyway. The goal of government is not to borrow it is to spend to achieve public purpose.

The capacity to spend is not limited at all by the current or past fiscal balance. To say otherwise is a lie. The constraint facing government spending is not a financial one.

The question we have to ask is this: Are there currently real productive resources being underutilised that are available for sale (either in final product form or unemployed labour)?

If the answer is yes, then the budget position of the government is not expansionary enough. It might mean that there is an existing budget surplus that should be smaller all, more likely, the budget deficit needs to be larger and maintained as long as non-government spending is at a level that these real productive resources would remain idle without the government’s spending support.

The only limits on government spending are the available real resources, which are for sale in the currency that the government issues.

In other words, government spending and taxation decisions should ensure that there is sufficient spending capacity in both the public and private sectors such that there are no idle productive resources.

That sort of enquiry is a long way from the approach taken in this Grattan Institute report, which tries to confine the discussion to financial considerations that are largely irrelevant to a currency-issuing government.

The author claims that:

On any view, persistent large deficits can unfairly shift costs between generations, and reduce flexibility in a crisis.

There is a footnote attached to Kotlikoff at this point.

First, I have a view and a Phd in Economics and I don’t hold this view.

It is clear that the intergenerational equity requires that the costs of providing public infrastructure and services be matched in temporal terms with the cohort that enjoys the benefits of such provision.

Normally, that provides, even in mainstream economics, the justification for borrowing. Hence, running deficits to provide infrastructure and services whose benefits than greater than a short period is equitable, under the rules specified above.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would go one step further and argue that the borrowing was an artifact brought over from the convertible currency (gold standard) monetary system and is largely superfluous in a Fiat currency system.

As I have said in the past, MMT views public debt as private wealth and the interest payments as private income. The outstanding public debt is really just an expression of the accumulated budget deficits that have been run in the past. These budget deficits have added financial assets to the private sector, providing the demand for goods and services that have allowed us to maintain income growth. And that income growth has allowed us to save and accumulate financial assets at a far greater rate than we would have been able to without the deficits.

The only issues a progressive person might have with public debt would be the equity considerations of who owns the debt and whether there an equitable provision of private wealth coming from the deficits. There is a debate to be had about that, but there is no reason to obsess over the level of outstanding public debt.

The government can always honor its debt; it can never go bankrupt. There’s no question that the debt obligations will be met. There’s no risk. What’s more, this debt provides firms, households, and others in the private sector a vehicle to park their saved wealth in a risk-free form.

Please see my interview with the Harvard International Review (October 16, 2011) – Debt, Deficits, and Modern Monetary Theory – for more discussion of these principles.

But, in general, I would move to a no debt issuance system and do away with the sham that governments are funding their spending by issuing debt. In reality, as noted above, the government spending provides the assets which they just borrow back when they issue debt. It is an elaborate ruse to make something look different to what it is.

The author a little further on actually qualifies his early strident point and says that “the burden of interest payments transferred to future generations can be rationalized if the debt funds investments that benefit future generations”.

At that point, you realise he thinks that interest payments are a burden. To whom? The mainstream claim that the deficits have to be paid back with higher taxation.

But apart from that not remotely resembling what happens, taxation is about fine-tuning private purchasing power so as to maintain non-inflationary aggregate demand levels.

The neo-liberal chimera, bought by the Report author, is that taxes fund government spending.

Remember the 2009 interview that Ben Bernanke gave Scott Pelley from the US program 60 Minutes. Interviewer Pelley asks Bernanke:

Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?

Bernanke replied, reflecting a good understanding of what we call central bank operations (the way the Fed interacts with the member banks):

It’s not tax money. The banks have accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank, we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed.

Please read my blog – Bernanke on financial constraints – for more discussion on this point.

Where does the Grattan Institute acknowledge that reality?

Further on the author tries to claim Keynesian credentials (Page 29):

Classic Keynesian fiscal policy suggests that a country should have budget surpluses when the economy is growing strongly, and budget deficits when the risks of stalling are high. This approach is codified in the current government’s statement of fiscal strategy, ‘to achieve budget surpluses, on average, over the medium term’ … Given this strategy, the substantial budgetary stimulus that Australia employed at the bottom of the economic cycle needs to be counter-balanced by budget surpluses even at mid-points in the economic cycle.

To which I respond – no it does not suggest that at all. Classic Keynes (rather than Neo-classical synthesis Keynesianism) tells us that the budget should be whatever is required to maintain full employment given the spending and saving patterns of the non-government sector.

That might be a continuous surplus, an average budget balance of zero over the cycle, or a continuous and very large budget deficit. It all depends.

There is nothing sacrosanct about a budget surplus in isolation from what is happening in the rest of the economy.

At present, Australia has a current account deficit which is expected to increase and the private domestic sector is also returning to previous savings patterns in order to reduce the massive debt overhang that emerged during the credit-binge leading up to the crisis.

In those circumstances, it is highly likely that growth will require continuous support from budget deficits. It is true that if private investment growth strengthens and the economy approaches full capacity, then there may be some grounds for imposing net public spending restraint on the economy.

This would be justified if the government was satisfied that the expenditure mix between public and private was desirable (that is, at full capacity) and the economy was running out of real capacity to respond to the nominal aggregate demand growth.

But even in those circumstances a budget deficit may still be warranted given the spending decisions of the other sectors (external and private domestic).

A fiscal strategy that restrains net public spending to keep the economy below the inflation barrier does not, inevitably, mean a budget surplus is required either at a point of the cycle or averaged over a complete cycle.

A counter-cyclical fiscal strategy does mean that the government should achieve a surplus. To think otherwise is to demonstrate a lack of understanding of the main sectoral aggregates and why they interact at various levels of economic activity.

The concept of counter-cyclicality more correctly refers to the direction of change of the aggregate. The government should certainly not be expanding its deficit if the economy is already at full capacity and it is satisfied with the private spending mix. Such an expansion would be pro-cyclical. But holding a steady deficit where the external deficit is steady and the private domestic sector is saving overall and content with that outcome is not pro-cyclical.

Under those circumstances, growth would be steady, and, hopefully, sufficient to absorb all the available capacity.

The Australian government is currently pursuing a pro-cyclical fiscal strategy – that is, they are cutting their net discretionary spending at the same time that the economy is slowing. This is the anathema of sound fiscal policy conduct. The same can be said for all the governments that are imposing fiscal austerity on their waning economies.

Conclusion

I thought the story that should have been headlined this morning was the leaked report documented in this article in the Melbourne Age – Jobs scheme at high risk of fraud: report.

The privatised job placements scheme is a multi-billion dollar handout to the parasites the government has co-opted to manage the unemployed (Churches etc). The problem is that these greedy organisations have seen RORT in bright lights in front of them and indulged in massive fraud over the years that the privatised labour support system has been in place.

The neo-liberals think this is a wonderful scheme. But it neither does anything effective for the unemployed, it produces zero jobs, and it has attracted a feeding frenzy among these job services agencies all dining out on the government funding.

It is ineffective, wasteful and hugely immoral.

Why wasn’t that on all the TV programs today?

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Not as bad as this Bill, but the Guardian has failed the public as well. There has been the ludicrous contention that a spreadsheet error along with the influence on the part of one of the error’s authors is the primary justification of many of the world’s austerity programs.

Here is the most recent example of which I am aware, Graeber in the Guardian of 21 April: “A sea of mea culpas from politicians who have spent the last few years telling disabled pensioners to give up their bus passes and poor students to forgo college, all on the basis of a mistake?”

The role of this spreadsheet error it seems to me has been to fan the flames of an already existing fire, not the cause of the fire itself. I have yet to see any media pundits attempt to place the locus of what is an egregious error in its rightful context in the debate concerning the justification of austerity and the data relevant to its justification (of which of course there is virtually none).

This “meme” seems to belong to the same group that contends that JGs can’t possibly work because the numbers either won’t or can’t add up (take your pick) being used to fan the flames of already entrenched claims that JGs are a terrible idea.

One of the roots of this sort of thing it seems to me lies in the idea that data speak for themselves independently of an interpretive or explanatory context to make sense of them. Instead of playing the role of a methodological heuristic, albeit a bad one, this idea has morphed into an ideological dogma that has been and is being employed as a clumsy club to beat others, especially the vulnerable, into submitting to an egregiously unjust and economically unjustifiable political policy.

Yes Indeed Bill. I’ve just been re-reading Victor Quirk’s working paper – the problem of a full employment economy on when the labour movement of the Labor party was conned into the neoclassical synthesis.

I spent the evening yelling at Leigh Sales & Penny Wong on the ABC

At least you are not as bad as Ireland ………..yet.

This is a example of the “free to choose” thingy turned right around into a strange never ending vortex.

The states monopoly of violence is used to bail out private actors.

The market state in action.

http://www.rte.ie/news/business/2013/0422/384457-pensions-oecd/

“The state” for want of a better word will force people to invest their wages in the private pension “industry”

Not only that but the money cannot be spent internally on increasing domestic productivity.

What a strange place Europe has become.

Hi Bill,

Do you think Fran Kelly (ABC Radio National) has shares in blood pressure medication?

There was a moment this morning when I thought she was going to ask John Daley (who was spruiking the report) ‘shouldn’t we just treat a surplus or a deficit as an accounting entry, given the fact that the Commonwealth can’t run out of Australian currency because it issues the stuff, unlike the Eurozone countries who don’t issue the Euro? Isn’t a surplus or deficit for the Commonwealth just a barometer reading of the state of the economy and nothing more? Shouldn’t we be putting the emphasis on employing the 1.9 million people who currently tell the ABS they have no work and want to work, and have the benefit of their labour? Aren’t you just lobbying to drive up private sector debt to create more assets for your sponsors in the finance sector, and engender more public sector sell-offs and outsourcing to the other business interests who fund you?

I was waiting for her to let rip, honest I was.

I thought she was edging her way to that point when she asked:

… and he seemed to be walking right into her ambush:

I started to worry when she didn’t seize the moment – but instead asked him again – why are the politicians backing away from getting a surplus?

So I thought – this is the point where she guts this guy. Who doesn’t know the official unemployment rate is a completely inadequate measure of labour underutilisation? But no, again the moment passed…

Now, even someone who was just mildly curious might have challenged him to explain why it is ‘normal’ for a government that is the sovereign issuer of its own currency to tax and charge more than they spend. Not Fran Kelly:

George Orwell observed of Hitler that he commanded respect from Germans not because he promised them good times and an easy life, but because he promised them hardship and struggle, which made him sound as if he was giving them the unvarnished truth. “I’m not pandering to cheap popularity – I’m just getting you to face reality”. It’s the same device that austerity merchants rely on the world over today.

The alternative idea that a good minimum standard of living for all is perfectly feasible, sounds far-fetched to people even though it is obviously feasible if enough people have access to work that pays them a dignified wage, which is totally within the means of the Commonwealth, and we have the productive capacity to supply to them what their wages will purchase, which we clearly do.

Hitler also had an ideological framework built on frequently asserted foundational assumptions that no one questioned, and that could not have borne rational scrutiny had they done so. Good thing we have a well-informed, free and fearless press today, eh Bill?

Cheers.

Victor Q

Well I’m glad I missed the Fran Kelly interview Victor as I’d now be footing the bill for a new Walkman.

Hearing Chris Richardson saying we’ve been “living beyond our means” was more than enough for one day.

Budget deficit should be called Wealth Enhancing Spending because that what it is. It is spending that is not covered in taxes and therefore neutralised.

Nobody would oppose Government increasing wealth of it’s citizens.

I was watching a report on this last night, it really sickens me that people who clearly have no idea how the monetary system works can be paid top dollar for ‘expert’ opinions on the subject.

If I can explain the fundamentals of vertical and horizontal transactions to my totally uneducated mother, I fail to see how the leaders of our country can so critically fail to understand their own role in the economy.

What’s worse is that they talk about surpluses like they are within their control. It’s well known that automatic stabilizers will almost totally undo any government’s attempts to run a budget in contradiction with the needs of the private sector. The harder they crack the whip, the harder the private sector bucks.

Still Larry, Graeber’s article was a step in the right direction and is assists in making MMT more mainstream.