I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Several universities to avoid if you want to study economics

Today I am catching up on things I read last week. Each year, there are various publications provided to high school students telling them about all the programs that are on offer at Universities. The prospective students use these publications to help them decide which program they want to pursue after high school and at which university or other higher educational establishment they might want to pursue it at. There is a lot of lobbying by institutions to get favourable reviews. But there is never a catalogue published which advises students where not to study. So today I am noting three economics departments which should be on the blacklist of any student who is considering undertaking the studies in that discipline. They are on my blacklist because of the questionable competency of at least some of their staff members. I will expand this list over time!

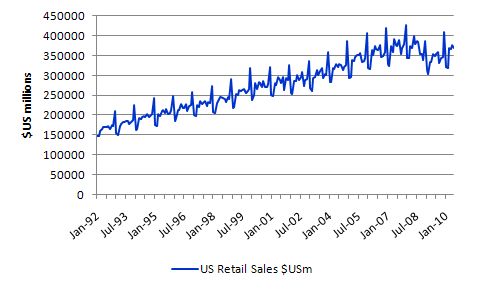

US retail sales

The following graph should tell you what you already know from your own experience. During major holiday periods you spend more than you do usually. We all do that – to buy gifts, take vacations, etc. Consumption spending goes up at certain times in the year and this means that aggregate demand increases during these periods and contracts again during non-holiday periods.

There is nothing extraordinary about that. Except that a couple of US professors from Chicago and Harvard do not seem to understand it. In that context, I caution anyone thinking of studying economics with these characters.

Further, given that the Harvard professor is our favourite macroeconomics textbook writer, I extend my advice to students contemplating studying economics at any place where his book is in use. You will learn nothing about how the economy operates but leave the institution confused and full of nonsense instead.

The US Census Department published very detailed retail sales data which is the major area in which aggregate demand varies on a seasonal basis.

So if aggregate demand is rationing employment that ration fluctuates on a seasonal basis. That should be a pretty easy thing to get our heads around.

Rationed employment – short-side rules!

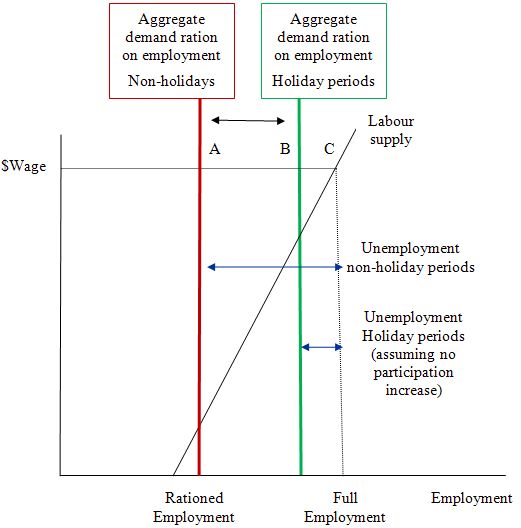

The following diagram shows what is going on. This is a stylised labour market with the wage ($Wage) on the vertical axis and Total employment on the horizontal axis in persons.

The wage is in nominal terms (as in Keynesian thinking) because the real wage is not determined exclusively in the labour market.

The labour supply is upward sloping indicates that for given price expectations more workers will be willing to work at higher real wages (that is, higher nominal wages in this diagram). This is a controversial issue and mainstream economists think this curve (line) is very sloping (meaning a strong supply response to real wage changes – including non-wage components like tax rates).

The empirical reality is that at the macroeconomic level this curve is virtually vertical. I have drawn it with a noticeable slope to make the point graphically – that is, I needed some horizontal space to shift other lines and it would have become too messy had I not drawn it such.

If the current money wage on offer in the macroeconomy (which is some weighted-average of alll wages) is $Wage we can see that it would be consistent with full employment (Point C). If firms offered that much employment then all workers who wanted to work at $Wage could find a job and all firms who were prepared to offer $Wage could find a worker.

So $Wage is capable of supporting sufficient aggregate demand to fully employment the available labour supply.

Now in macroeconomics the labour demand curve is derived from what Keynesian (and MMT) economists call the product market – that is, from the sum of all goods and services on sale at any point in time. Firms will not employ people to produce if they cannot sell the output.

So we think of aggregate demand as imposing an employment ration on the labour market via some (implied) productivity relationship. Aggregate demand determines how much output will sell and so firms produce that much.

Labour productivity tells the firms how many workers they will need to make the given output. So there is an employment requirements function implied in this diagram (it would be above the graph shown if I was to present this as a multi-part diagram).

During non-holiday periods the aggregate demand ration is given by the RED vertical demand for labour line. So the economy is employing well below full employment at Point A (given $Wage) and unemployment is given by the distance between A and C.

You can see that workers at $Wage are willing to work out to C but are constrained by the aggregate demand ration.

During holiday periods, aggregate demand increases (temporarily) as people go on holidays etc and the ration shifts out to the GREEN vertical line.

Firms are now willing to take on extra staff (in shops, seaside resorts etc) and so employment increases to B.

Assuming no labour participation response (which is not realistic but doesn’t alter this point – in fact, participation is likely to increase), then unemployment is now the distance B to C as employment has expanded.

Once the holidays are over, the labour market contracts again and unemployment rises.

At all times (employment levels below Point C), the workers are not getting enough work to satisfy their preferences.

So the short-side of the market (the aggregate demand constraint) is always driving the observed outcomes. The supply-side of the labour market merely reacts to shifts in the short-side but never determines the outcome.

The workers are “always of the supply curve” is the jargon. This means that whatever preferences for combinations of wages and employment are embodied in the labour supply function they never bind on the actual outcome while there is a demand ration in the labour market.

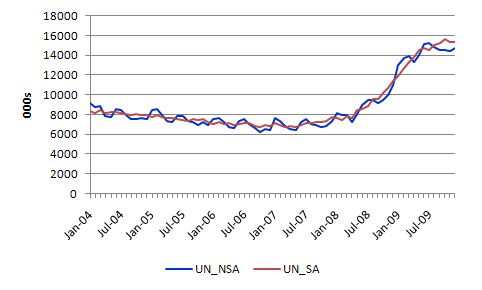

In fact, the labour supply does swell in the holiday periods with the new entrants coming in after school finishes. The next diagram taken from US Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows official US unemployment from January 2004 to December 2009. The blue line is seasonally unadjusted time series and the red line is the adjusted series.

The blue line peaks during the holiday period and by the end of each year has troughed. If I graphed employment you would see that it rises and falls with the season as well.

But the essential point is that these seasonal patterns tell us very little about the “disincentives” that exist in the macroeconomy on the supply side. The aggregate demand impacts swamp any supply responses in times of rationed demand.

So how does the mainstream construct this?

The New York Times runs a column they call Economix which carries the authoritative sub-title Explaining the Science of Everyday Life. On August 11, 2010 the column was written by Casey Mulligan who is an economics professor at the University of Chicago.

Warning: prospective students – do not study economics at this University.

Mulligan’s article – The Seasonal Job Surge: 2010 Edition – was a pathetic attempt to reclaim the debate that the mainstream has lost badly since the crisis began.

He says:

National employment has increased by three million since January, and the change tells us a lot about how the labor market operates. The headline from Friday’s employment report was that employment was lower in July than in the previous month and has hardly recovered since the beginning of the year. That headline report does not refer to actual estimates of employed persons, but rather to seasonally adjusted estimates.

The fact is that national employment was two million to three million higher in July than it was six months before …. If previous seasonal patterns continue, much of that increase is expected to reverse itself by January. So, at first glance, there is no reason to get excited about the actual two million to three million increase.

But it’s big news that the seasonal employment cycle continues to operate as normal. The cycle is, of course, the outcome of seasonal fluctuations in supply and demand, and Keynesian economists insist that supply and demand are not operating normally since the recession began and that the economy has been caught in a “liquidity trap.”

Keynesian economists claim that labor supply – the willingness of people to work – doesn’t matter right now … which is why they advocate government stimuli that increase spending even while they erode work incentives. As Paul Krugman put it: “What’s limiting employment now is lack of demand for the things workers produce. Their incentives to seek work are, for now, irrelevant.”

This is not what “Keynesians” say at all. They say that in a situation where there the “market” is rationed the short-side of the market rules. In these situations, if the demand side is rationing employment at a given wage then the “supply” intentions of the workers are irrelevant. The diagram above makes that patently obvious.

It doesn’t mean that supply will not increase. Clearly, if the ration eases then unemployed workers will be happy to take the jobs that would be offered. The supply intentions of the workers (in our diagram) do not become binding on anything until the ration intersects the supply function at the current wage rate.

So Mulligan’s attempts to score some points in this case is really laughable.

The reason that the “seasonal employment cycle continues to operate as normal” says nothing about the validity of the notion that aggregate demand drives employment under typical circumstances.

The point Mulligan wants to make is this:

My view is that the stimulus law is partly responsible for today’s low employment, precisely because so many of its components have eroded work incentives. That’s why it’s so important to know whether supply operates as normal …

People can argue about whether supply effects are marginally smaller during a recession. But the seasonal cycle clearly shows that labor supply remains important and cannot be approximated as a nonfactor, or even a sharply diminished factor, in today’s employment fluctuations.

It is clear that as the demand ration eases, frustrated workers will be in a position to take more jobs. Even in a recession, aggregate demand follows a seasonal pattern which reflects the changing pattern of our lives over the course of the cycle.

What is not often appreciated is that even in a recession, 90 per cent of the workforce remains employment and spending (for example, in the US). The workers who keep their jobs might spend less because they fear dismissal or are being put on shorter hours. But they still go on spending and that spending has a seasonal pattern.

The aggregate demand ration thus behaves in a seasonal manner. And so the constraint on labour supply also behaves seasonally as does employment.

Next day (Thursday, August 12, 2010), Harvard professor Greg Mankiw in his blog – A Challenge to Extreme Keynesians – also thinks the Mulligan argument is worth some attention.

Prospective students – do not study economics at Harvard. Not only because Mankiw is there but you will also run into Rogoff and Barro and other non-entities in the “science of explaining everyday life”.

Mankiw claims that the:

The key insight of Keynesian economics is that the problem during recessions is inadequate aggregate demand. Taken to the extreme, which some Keynesians do, it says that aggregate demand is the only thing you need to worry about during downturns. Changes in aggregate supply (due to, say, high marginal tax rates or adverse incentives associated unemployment insurance) don’t matter, they argue, because employment is being constrained by the low level of aggregate demand.

… But if aggregate demand were the main constraint on employment, this increase in supply should not translate into higher employment during deep recessions such as this one. But it does!

I wouldn’t study under someone who offered that comment as something we should take seriously.

Aggregate demand can still be the main constraint on employment and you will still get supply increases if the demand constraint eases (during holidays or otherwise). That observation proves nothing at all about the impact of disincentives.

The Economist Magazine also challenged the Mulligan-Mankiw line but chose to highlight non-demand constraint issues and in that sense did not get to the nub of the issue.

Next we go across town in Boston …

Boston is one of my favourite cities and I love going there and I do so too infrequently. But it harbours some really hard-line mainstream macroeconomists (as in Harvard). A professor at Boston University also made headlines last week and, in doing so, qualified his Department for the billy blog “avoid at all costs if you are a student” award. So this week, Chicago, Harvard and Boston.

In the Bloomberg opinion spot last week (August 11, 2010) there was a stunnig article written by Laurence Kotlikoff, an economics professor at Boston University. Talk about inflation – if this guy is an economics professor then standards have really slipped.

In the Op Ed article – U.S. Is Bankrupt and We Don’t Even Know – Kotlikoff said:

Let’s get real. The U.S. is bankrupt. Neither spending more nor taxing less will help the country pay its bills.

Parts of the private sector in the US become bankrupt every day. That occurs when financially-constrained entities cannot meet their contractual obligations in the currency of issue. It might also arise when such an entity cannot meet their foreign-currency denominated contracts although depending on the way those contracts are drawn up bankrupcy might not be inevitable.

But whatever, the US government can never become bankrupt unless it chooses to default on its financial obligations for political reasons. I would estimate there will never be a situation where it will do such a thing so I venture to say that the US government is risk-free.

Why? Answer: simply because it issues the US dollar as a monopolist and has no financial obligations denominated in any other currency.

So let’s get real. The US is not bankrupt in fiscal terms. In fact, given the state of the real economy the public deficit is not large enough to support higher levels of economic activity.

Kotlikoff then claimed that the IMF “welcomed the … [US] … authorities’ commitment to fiscal stabilization, but noted that a larger than budgeted adjustment would be required to stabilize debt-to-GDP.” So what? The gyrations in the debt-to-GDP ratio tell you nothing about solvency at all.

They are largely driven by economic growth and interest rates. Interest rates are around zero at present (bond yields are stable if not falling as the bond markets continue to demand US government paper). US economic growth is wavering and likely to flatten some more in coming months. So the debt ratio will rise if only because the automatic stabilisers will push up the deficit some more and the US government voluntarily issues debt $-for-$ to match its net spending.

That voluntary decision is totally unnecessary but it does it to appease the neo-liberals.

But Kotlikoff goes further and claims that the:

… IMF has effectively pronounced the U.S. bankrupt. Section 6 of the July 2010 Selected Issues Paper says: “The U.S. fiscal gap associated with today’s federal fiscal policy is huge for plausible discount rates.” It adds that “closing the fiscal gap requires a permanent annual fiscal adjustment equal to about 14 percent of U.S. GDP.”

The fiscal gap is the value today (the present value) of the difference between projected spending (including servicing official debt) and projected revenue in all future years.

So what? The IMF’s version of fiscal sustainability bears no relationship to the actual level of net spending that is required to support public purpose in a sovereign economy.

There is no reason for the “fiscal gap” (the deficit) to be closed – now, tomorrow or ever. The public budget balance reflects mostly the state of private spending (and saving) decisions. If the private sector desire to save overall which is currently the case in the US at present as debt deleveraging gathers pace and the external sector is in deficit (which is typical) then there is no choice – the budget has to be in deficit.

Under these conditions, the deficit can either be a “good” one – which means it reflects the government’s commitment to maintain high levels of economic growth which enables the private sector to realise their desires to increase saving (because it stimulated income growth).

Or it can be a “bad” deficit – which results when governments panic and try to cut the deficit (as Kotlikoff demands) and the aggregate demand contraction leads to falling economic activity, rising unemployment, falling tax revenue and growing net public spending via the automatic stabilisers.

Please read the trilogy of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – for more information on this.

Kotlikoff claims that the IMF prescription would require:

… an immediate and permanent doubling of our personal-income, corporate and federal taxes as well as the payroll levy … Such a tax hike would leave the U.S. running a surplus equal to 5 percent of GDP this year, rather than a 9 percent deficit. So the IMF is really saying the U.S. needs to run a huge surplus now and for many years to come to pay for the spending that is scheduled. It’s also saying the longer the country waits to make tough fiscal adjustments, the more painful they will be.

Is the IMF bonkers?

No. It has done its homework.

It is highly unlikely that the US government would achieve a surplus under these conditions. The fiscal drag that would result from the tax hikes would melt aggregate demand and the economy would plunge back into recession – deeper than before. The result – a “bad” deficit.

The only way governments can run surpluses when their external sectors are draining demand via current account deficits is to rely on the private domestic sector being in deficit. These deficits are funded by increasing private indebtedness and for a time can keep aggregate demand growing at a sufficient pace to maintain economic growth.

But this sort of strategy is unsustainable because the private domestic sector cannot sustain deficits. Eventually, as we are seeing now, the credit binge has to come to an end and the private domestic sector start saving overall. Then the public balance is unable to remain in surplus.

Kotlikoff appears to totally misunderstand these essential macroeconomic relationships.

Kotlikoff then does some creative but meaningles arithmetic to conclude that the US “fiscal gap … is more than 15 times the official debt”. The “gargantuan discrepancy between our “official” debt and our actual net indebtedness” relates, according to Kotlikoff, to the unsustainable public exposure to the demographic transitions (ageing) that are occurring.

He says:

How can the fiscal gap be so enormous?

Simple. We have 78 million baby boomers who, when fully retired, will collect benefits from Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid that, on average, exceed per-capita GDP. The annual costs of these entitlements will total about $4 trillion in today’s dollars. Yes, our economy will be bigger in 20 years, but not big enough to handle this size load year after year.

This is what happens when you run a massive Ponzi scheme for six decades straight, taking ever larger resources from the young and giving them to the old while promising the young their eventual turn at passing the generational buck.

The US government will always be able to fund the Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid schemes in US dollars should there be a political will to do so. The only constraints it may encounter are real resource constraints – there might not be enough materials etc to buy. I suspect that is unlikely. At any rate, these are not the constraints that Kotlikoff is trying to whip up a frenzy over.

Please read my blogs – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time and Democracy, accountability and more intergenerational nonsense – for more discussion on this point.

But running deficits is not remotely like a ponzi scheme, which is a:

… fraudulent investment operation that pays returns to separate investors from their own money or money paid by subsequent investors, rather than from any actual profit earned. The Ponzi scheme usually entices new investors by offering returns other investments cannot guarantee, in the form of short-term returns that are either abnormally high or unusually consistent. The perpetuation of the returns that a Ponzi scheme advertises and pays requires an ever-increasing flow of money from investors to keep the scheme going.

The budget of a sovereign government which is not revenue-constrained is not remotely like this. There is no valid analogy. Such a government never needs to raise revenue to spend and only raises revenue (in concept) to ensure there is enough non-inflationary aggregate demand space for them to pursue a social-economic program.

Some revenue measures have other intentions (such as, discouraging harmful behaviour etc) but no revenue measure is necessary to underpin government spending.

Further, each generation chooses its own tax burden and this is independent of that chosen by the last generation. Our children will never pay for the deficits of today. They may enjoy the benefits of them – better infrastructure, higher employment levels for their parents, better education etc – but there will never be a bill sent to them to pay for these benefits.

Kotlikoff ramps up the scare-mongering by claiming that the US is living on borrowed time and that the:

… first possibility is massive benefit cuts visited on the baby boomers in retirement. The second is astronomical tax increases that leave the young with little incentive to work and save. And the third is the government simply printing vast quantities of money to cover its bills.

Have we ever seen such draconian shifts in US fiscal policy? Answer: Never.

Why not? Answer: because deficits are never paid back!

Kotlikoff thinks the US is in “worse fiscal shape than Greece”. Really? Juxtapose that with his earlier claim that the US govermnent might resort to “simply printing vast quantities of money to cover its bills”. The Greek government cannot do that. Why not? Answer: it is not sovereign in its own currency.

There is no comparison between any EMU nation and the US economy in terms of the risk of fiscal solvency. The former are exposed to fiscal default all the time whereas the latter is never a solvency risk.

And then to bring the theme of this blog back into harmony, Kotlikoff gets on the bash the Keynesians bandwagon:

Some doctrinaire Keynesian economists would say any stimulus over the next few years won’t affect our ability to deal with deficits in the long run.

This is wrong as a simple matter of arithmetic. The fiscal gap is the government’s credit-card bill and each year’s 14 percent of GDP is the interest on that bill. If it doesn’t pay this year’s interest, it will be added to the balance.

When hasn’t the US government paid its interest bill? Answer: Never.

I am not a “doctrinaire Keynesian economist” but I say that the only way the US economy will get itself of the “real” mess it is in – which is the stagnant demand and persistently high unemployment – is for a further fiscal injection to be made. This should be preferably focused on public sector job creation.

The government doesn’t have a credit card in the same way that households or firms do. This household analogy is inapplicable to a sovereign government which is not revenue constrained.

You might want to listen to MMT proponent Mike Norman talking about Kotlikoff in more direct terms than I have written here on the Washington-based news channel RT America. It is very entertaining but scary.

I urge all you Bostonians who care to write to Kotlikoff – kotlikoff@bu.edu – and provide him with some local counselling service contacts please. He is in serious need of some intervention.

Conclusion

The mainstream economics input into the policy debate is really becoming hysterical. The arguments I have considered in this blog are really stretching the limits of absurdity.

I think I need a rest from them, so ….

That is enough for today!

Is Modern Macro Useful for Development Economics (and Economists)? by Jamus Lim

Another great post. I’m not as yet optimistic that reality can overtake the Neo-Classical propaganda machine, enabled by a court that advances rights to money and corporations while constricting them for human, anywhere short of a collapse. But thanks for hammering out reality every day!

Dear Bill:

I have been reading you and others on MMT for about 6 months now and learning very much. A rare revelation! Thank you for deconstructing all of these current opinions for us. I am now much better able to understand current policy discussions.

At some time could you explain more what is happening in Europe. I read this article last week, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/14/world/europe/14germany.html?ref=europe, about Germany’s success. The thrust of the article seems to imply that Merkel’s austerity push has been successful. But it is also noted that there is a Short Work program that keeps workers employed, rather than laid-off, which would have an important effect, and it must be government funded. I would be interested in understanding better the magnitudes and interactions of the various policies Germany has taken which make it different from other Eurozone countries.

Thank you and best regards,

Jim Thomson

Port Townsend, Washington, USA

the US government can never become bankrupt unless it chooses to default on its financial obligations for political reasons. US debt is even safer than that, as the US government cannot legally, constitutionally choose to default on its financial obligations. The 5th and 14th Amendments and a long line of Supreme Court cases say different, and say that even the US Congress, unlike the legislature in a parliamentary system, does not have the power to repudiate some obligations, like bonds, that it has made. This does happen in practice. Just last year Congress passed a law that seemed to stiff contractual obligations, much less clear than bonds, due ACORN. But the executive, citing this body of law, interpreted it otherwise and paid hapless, friendless ACORN what it was due.

Dear Jim,

Interesting comment.

I believe that, despite what was said, the Germans did stimulate their economy as well as receiving a boost from net exports by the fall in the Euro.

I also read that the German economy is a couple of quarters behind the US. If you remember there was a fairly large increase in US output before ‘growth’ fell back.

John:

Thanks for the reply. I also, as you do, suspect that there must be significant stimulus of the German economy, although, as you say, not much spoken about. Certainly the Short Work program would be a stimulus of the nature of a very limited Jobs Guarantee type. It seems what is higlighted is the “austerity” policy. The large German trade suplus must also be a factor.

I don’t have the resources or background to understand how Germany functions within the Eurorzone monetary system, which imposes different constraints than on sovereign governments.

My initial, rather uninformed take on this is that it is possible that whet stimulus there was was extremely well targeted and effective, even within a general policy of austerity.

Dear Bill,

Just to show that I try to read every word!

” the US economy will get itself of the “real” mess it …”

Left out an ‘out’?

I’m particularly concerned with your immediate response to the Kotlikoff article. I’ll be the first to admit that his (op-ed) writing style induces immediate rejection because of the incessant fear-mongering. However, after letting it digest for a while, it’s really not all that crazy. The first thing you say after posting a quote of his is:

“But whatever, the US government can never become bankrupt unless it chooses to default on its financial obligations for political reasons. I would estimate there will never be a situation where it will do such a thing so I venture to say that the US government is risk-free.”

Such a statement suggests that he didn’t make one of his underlying points clear enough to you. He’s trying to say that assuming that the US government is risk-free as a starting point is perhaps a very dangerous assumption. Sure, many (if not most) investors world-wide make this assumption. But he’s trying to rationalize why we continue to make this assumption. If a private company continued to issue debt despite the fact that it was racking up expenses that far exceeded projected revenues, one would expect that the price of this debt would approach zero. Granted, the US government is not like a private company in one key difference, it can print money. So I think what Kotlikoff is saying is that if it does not change it’s policies in a matter sufficient to bring it’s expenses and revenues in line, then the only other recourse is to print money. Like you said, you “estimate that there will never be a situation where it will do such a thing [as choosing to default for political reason]…” He agrees that the US would never officially default. So much of his doom-saying is related to the fact that printing money isn’t really a viable solution because that would be disastrous for the US economy. He’s just trying to draw attention to the fact that a few hundred billion dollar budget adjustments (which is what we usually see going on in Washington) aren’t going to be enough to bring the budget in line.

I understand that it’s difficult to power through his op-ed articles because they elicit such a visceral response. But I’ve given them some prolonged thought and I’ve convinced myself that he’s got a pretty good point.

“Further, each generation chooses its own tax burden and this is independent of that chosen by the last generation. Our children will never pay for the deficits of today.”

I am fairly uninformed but trying to understand this issue. If deficits contribute to a growing economy, and taxes reduce private spending, then why not simply cut taxes to zero and spend purely out of deficit?

My answers to the above 2 questions:

@cm: If deficits contribute to a growing economy, and taxes reduce private spending, then why not simply cut taxes to zero and spend purely out of deficit? Taxes are necessary because they create the initial demand for currency. Why would anyone want this worthless paper or even more worthless electronic score in some computer if there were not a real need for it? If the supply (spending) exceeds the demand (ultimately driven by taxation) too much, we will get inflation. A minimal, Austrian-libertarian goverment could get by on very low taxes.

@ Paul : So much of his doom-saying is related to the fact that printing money isn’t really a viable solution because that would be disastrous for the US economy. Why? – The answer is that it would not be disastrous. As Michael Kalecki pointed out long ago – see https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=11127, what governments do right now is equivalent to “printing bonds” – engaging in government spending by giving bonds to the public in exchange for real goods.

Contrary to common, but unthinking belief, the difference between “Printing money” (spending without issuing debt) and spending while issuing debt – purportedly “borrowing” – in reality to maintain an interest rate, is trivial. Currency and bonds are merely two kinds of government IOUs. It’s not that one is a Real Thing and the other a promise to provide this scarce Real Thing in the future.

There is no need for a government to “bring its expenses and revenues in line”. Why should anyone care about that? Balanced budgets, and even more, surpluses, are usually quite bad for a real economy. Deficit spending is normal and healthy for a growing economy and population. What is important is that resources not be squandered – that they be fully employed – particularly human resources – and a distant second, that prices be stable. Kotlikoff’s proposals are sheer lunacy – the kind of thing a conquering nation might do to subjugate a defeated one. MMT pays close attention to what is happening in the nominal, monetary world – and shows that if we stop being hypnotized by imaginary problems, we can build a much better real one, with ease, by simply not destroying enormous quantities of wealth. Real world wealth is what backs up the government promises to fulfill its promises to its population in the future, not some numbers in a computer.

I guess I’m trying to figure out how the US government will actually be able to honor its promises to its population. I’m not so concerned with annual deficits or surpluses. I understand deficit spending. I’m talking about forward looking concerns over longer horizons. I just look at future tax revenue projections (from various places, like the CBO or my own) and future expenditures/commitments and while there is certainly a considerable deal of variance surrounding these estimates, the general result points to a rather sizable gap in the wrong direction. So given that and the outstanding US debt, I worry where is the money coming from. I’m not comfortable enough to put my faith in real world wealth as a means for the government to actually honor its commitments.

Paul,

I think you are too focused on financial projections into the future which are notoriously inaccurate. According to MMT in a recession government spending should make up the shortfall in private spending but be limited by real world capacity constraints so as not to cause excessive inflation. Government spending does not disappear into a black hole, it winds up being someone’s asset. The bonds the government issues pay interest to someone. There are distributional issues with that, such as it is mostly high income earners who own the bonds, but that should be addressed through tax policy. MMT cannot resolve all of society’s problems: injustice still remains unless it is dealt with politically but at least under MMT false monetary issues can’t be used to justify those injustices.