I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Keynes would not support fiscal austerity

On Wednesday, we learned that the real GDP growth rate had halved in the December 2011 quarter (to 0.4 per cent) and business investment had contracted. Next day, we learned that the Australian labour market has deteriorated with employment contracting, unemployment rising and since November 2010, 140 odd thousand workers have left the labour force, presumably because employment growth had stalled. We already know that 2011 was a jobless year. Today, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released their International Trade in Goods and Services for January 2012, which shows that our trade balance went from a $A1325 million surplus to a $A673 million deficit (a “turnaround of $1,998m”). Unless that changes in the coming months, the contribution to growth from net exports will be solidly negative. All of these events have reduced the tax revenue for the government. But the response of the Government, which is pursuing a budget surplus this year at all costs, is that they will now have to cut their spending harder. Last year, the Treasurer claimed the authority for this pursuit was none other than John Maynard Keynes. More recently, the British Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills claimed – Keynes would be on our side – in relation to the imposition of fiscal austerity. The reality is otherwise – Keynes would not support fiscal austerity under the current circumstances. The strategy is bereft of any credible authority and is being driven, variously, by politics and ideology.

When you visit the Australian government Budget 2011-12 homepage you are immediately met with the following, bold statement:

The Budget will get back to surplus in 2012-13 as planned, get more people into jobs and spread the opportunities from Mining Boom Mark II to more Australians.

The statement was formulated in May 2011 at the time the last Federal budget was delivered by the Treasurer.

10 months later all those predictions (promises) are unlikely to be true by the time the next budget is delivered in two months time.

Even in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook delivered in December 2011, the Treasurer was still talking up these promises. They acknowledged that:

… significant global headwinds are weighing heavily on Australia’s economic and fiscal outlook … [but] … the Government remains on track to deliver a budget surplus in 2012-13 … downward revision to the economic outlook from Budget has reduced tax receipts by over $20 billion over the forward estimates. Lower employment growth since Budget is impacting on taxes on wages and salaries, and volatile financial markets are affecting equity prices and hence capital gains receipts.

But despite this “While the revised outlook for revenue has made the return to surplus more difficult than at Budget, the European sovereign debt crisis has underscored the importance of maintaining fiscal credibility”.

Most recently, after the National Accounts data came out on Wednesday, the Treasurer was at it again.

In the ABC report (March 7, 2011) – Surplus in the spotlight as economy slows – the Treasurer was quoted as saying:

I believe it’s really important to return the budget to surplus … It sends a very clear message to the world that Australia is in good nick. If you want any reminder about the importance of that look again today at what’s going on around Europe … We’ve been exercising very considerable expenditure restraint to come back to surplus in 2012-13 … This is going to make this task harder, but we absolutely need to do it given the circumstances.

A budget surplus that was driven by growth. where we had full employment and private domestic saving overall was at desired levels, certainly would send a signal that our economy was strong and relying net exports for growth. Whether that was the best we could achieve, given an external surplus indicates we would be denying the local population access to imports, is another question. But a fully-employed growing economy that was satisfying non-government saving intentions is a far cry from where we are now.

At present, the Australian economy is languishing in low growth, with at least 14 or 15 per cent of its willing labour force not working (adding the hidden unemployed estimate to the official ABS broad labour underutilisation rate of 12.5 per cent), and the private domestic sector is trying to reduce its massive debt levels.

Further, what is going on in Europe is largely irrelevant to Australia. The EMU nations use a foreign currency and thus face solvency risk (and resulting bond market ambivalence when debt levels rise and growth stall) whereas Australia is fully sovereign in its own currency.

What the data is now telling us is that the “very considerable expenditure restraint” is damaging the economy and killing employment growth – and – is undermining its own intention – to create a budget surplus.

This was brought home emphatically by the Federal treasury boss Martin Parkinson (March 7, 2012) in his Introductory Remarks to the Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce.

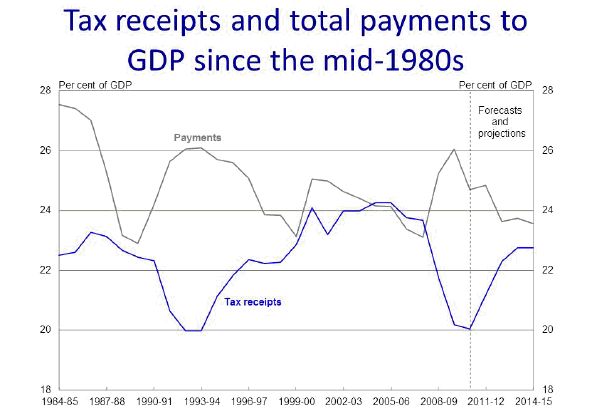

He produced this graph which shows how far federal revenue has fallen as a per cent of GDP since the crisis began.

In relation to the graph, the Treasury Secretary said:

The tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen by 4 percentage points since the GFC, and is not expected to recover to its pre-crisis level for many years to come. This reflects a combination of cyclical and structural factors. Capital gains tax has been hit hard in the aftermath of the crisis. Households are more cautious in their spending pattern, dampening indirect taxes in the process. Meanwhile, the resources boom and the increasing importance of the mining sector is having significant impact on tax revenues. Mining companies account for about a fifth of gross operating surplus, yet only around a tenth of company tax receipts, primarily because tax receipts from the industry are affected by the high levels of investment occurring in the sector and the consequent level of depreciation deductions. Finally, the historically high Australian dollar hurts profits in, and taxes from, the non-mining export, and import-competing, sectors.

In the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook the Government was forecasting real GDP growth would be 3.25 per cent for 2011-12. It is already around 2.5 per cent (as at December 2011 quarter) and falling fast. It will be lucky to come in above 2 per cent by the time the fiscal year is out (June 2012).

The May 2011 Budget forecast employment growth at 1.75 per cent and this was revised down to 1 per cent in the December review. However, employment growth in 2011 was zero and yesterday we learned that total employment was contracting.

Most of the other real-sector forecasts were overly optimistic which is something I said at the time before the data had come out.

The impact is that tax revenue continues to slump which led the Treasury Secretary to conclude that “surpluses are likely to remain at best razor-thin without deliberate efforts to significantly increase revenue or reduce expenditure”.

I would go further and say that the Government will not be able to achieve a surplus in the coming year given the current economic activity.

Where does this obsession with surpluses come from?

In 2011, the Treasurer wrote an essay – Keynesians in the recovery where he tried to put an intellectual stamp on the surplus obsession. He wrote:

If we are going to be Keynesians in the downturn, we have to be Keynesians on the way up again. That means a speedy return to surplus … I want to explain how one of the 20th Century’s great thinkers, John Maynard Keynes, helped us find the answer, in the process influencing the Government’s response to both the global downturn and our strategy for the recovery. More broadly, I want to describe how economic policy informs the delivery of not just responsible management but a modern progressive agenda. Most importantly, I want to make the point that being a Keynesian means supporting a counter-cyclical fiscal policy with government making room for the private sector when economic growth is strong.

The early part of the Essay was about the Keynesian-motivation for the Government’s fiscal stimulus in late 2008/early 2009. That intervention was a sound strategy but was neither large enough nor targetted enough at jobs. The consequence was that the Australian economy avoided the recession (mostly) but labour underutilisation rose.

However, as I have argued on many occasions, here and in my public presentations and media appearances, the fiscal stimulus saved us from a major European-US style recession and thousands of jobs were saved as a consequence.

But while we are in better shape than most of the advanced nations, the latest data shows that we are a long way from achieving full employment (and inflation is stable and low). That means that now is not the time to be contracting net public spending.

After claiming authority for the stimulus in Keynes, the Treasurer then went on to talk about what Keynes would be doing in the “recovery”. He wrote:

One important aspect of Keynes’ work that has been deliberately under-emphasised by conservative critics is that phrase “counter-cyclical” – because it implies the opposite of the critics’ claim that Keynesian policies constitute a recipe for ever-increasing rates of public spending as a proportion of GDP.

Which was brought him to the “main point of his essay”:

… once growth and prosperity have been restored, they have an equal responsibility to restrain public expenditure, budget for surpluses and reduce debt in climbing out.

This statement is deeply flawed and demonstrated that the Treasurer (and whoever wrote this essay) doesn’t have a solid grasp of either Keynes or macroeconomics.

First, Australia has not restored its pre-crisis prosperity. Even before the crisis, the ABS estimated that the broad labour underutilisation rate was 9.5 per cent. So we were a long way from full employment then. That rate stands at 12.5 per cent now and is an underestimate of the current state of labour wastage. The point is that there is a long way to go just to regain the ground lost during the crisis.

Second, and more substantively in terms of my criticism, restraining public spending growth and budgeting for surpluses are not equivalent. A budget balance is always the net outcome of government spending and revenue policies interacting with non-government spending and saving decisions.

We say that the budget outcome is endogenous, which means that it is determined by the system, in general, rather than the specific policy decisions taken by government.

In fact, the government cannot realistically target a budget outcome because changes in private spending can thwart any efforts made by the government to achieve that target.

Indeed, we have seen that in the current period, many governments imposing fiscal austerity onto their economies with the intended purpose of reducing the budget deficits, but are, instead, seeing their budget deficits rise (or not falling as quickly as planned) because private spending is not responding in the way they envisaged.

In this regard, the sensible strategy for a government is to target full employment and allow the budget balance to be whatever it takes to achieve that goal. The government can always achieve a given employment target because it can run a buffer stock of jobs (which I call the Job Guarantee) which would ensure that anyone who wants a job but cannot find one elsewhere can work for pay in the public sector.

The other point is that there is nothing sacrosanct about a budget surplus in isolation from what is happening in the rest of the economy.

At present, Australia has a current account deficit which is expected to increase and the private domestic sector is also returning to previous savings patterns in order to reduce the massive debt overhang that emerged during the credit-binge leading up to the crisis.

In those circumstances, it is highly likely that growth will require continuous support from budget deficits. It is true that if private investment growth strengthens and the economy approaches full capacity, then there may be some grounds for imposing net public spending restraint on the economy.

This would be justified if the government was satisfied that the expenditure mix between public and private was desirable (that is, at full capacity) and the economy was running out of real capacity to respond to the nominal aggregate demand growth.

But even in those circumstances a budget deficit may still be warranted given the spending decisions of the other sectors (external and private domestic).

A fiscal strategy that restrains net public spending to keep the economy below the inflation barrier does not, inevitably, mean a budget surplus is required.

A counter-cyclical fiscal strategy does not mean that the government should achieve a surplus. To think otherwise is to demonstrate a lack of understanding of the main sectoral aggregates and why they interact at various levels of economic activity.

The concept of counter-cyclicality more correctly refers to the direction of change of the aggregate. The government should certainly not be expanding its deficit if the economy is already at full capacity and it is satisfied with the private spending mix. Such an expansion would be pro-cyclical. But holding a steady deficit where the external deficit is steady and the private domestic sector is saving overall and content with that outcome is not pro-cyclical.

Under those circumstances, growth would be steady, and, hopefully, sufficient to absorb all the available capacity.

The Australian government is currently pursuing a pro-cyclical fiscal strategy – that is, they are cutting their net discretionary spending at the same time that the economy is slowing. This is the anathema of sound fiscal policy conduct. The same can be said for all the governments that are imposing fiscal austerity on their waning economies.

So even using the Treasurer’s own logic, the Australian government is not behaving as Keynes would have recommended. In other words, the Treasurer’s appeal to John Maynard Keynes as an authority for the obsessive pursuit of a budget surplus is pure cant. There is no economic (nor financial) justification for the Government’s current surplus obsession.

It is being driven purely by politics. The Opposition (who claims they would run even larger surpluses) have cornered the Government and they both think the electorate will judge them on the size of the surplus. However, it is more likely that the electorate will conclude the current Government has failed if our growth rate continues to decline and unemployment continues to rise.

Third, no one who really understands these matters talks in terms of levels of debt. Discussions about debt can only make sense if we talk in terms of scaled debt (that is, public debt ratios). An economy can have expanding levels of debt but falling debt ratios as a result of growth. That said, there is very little informational content to be gleaned from examining movements in public debt ratios.

What we can say is that non-government wealth rises when public debt levels are rising. That is about all.

The obsessive nature of the Government’s pursuit of surpluses and why they are not “Keynesian” in spirit is demonstrated by a further statement the Treasurer makes in his Fabian essay. He is talking about the Government’s commitment to achieving a surplus in the coming fiscal year:

This strategy hasn’t and shouldn’t change in light of recent events at home and abroad … [various negative events] … will reduce growth and tax revenue in coming quarters …

But still they will pursue the surplus at all costs!

As noted at the outset, other world leaders have appealed to Keynes as they hack into net public spending as their economies go down the drain.

There was an article in the UK Magazine the New Statesman (January 12, 2011) – Keynes would be on our side – by Vince Cable, British Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills.

This was responded to the following fortnight (January 19, 2011) by Keynes’ biographer Robert Skildesky and David Blanchflower in their article – Cable’s attempt to claim Keynes is well argued – but unconvincing.

I may offer some comments about this specific tit-for-tat in another blog. I obviously fall down on the Skidelsky/Blanchflower side but then only generally. They fall foul of flawed logic themselves. But we will leave that for another day.

The point is – did Keynes advocate balanced budgets over the course of the business cycle?

Researchers go back to Keynes 1924 Macmillan publication – A Tract on Monetary Reform – where he argued strongly that price stability was a policy target and this including avoidance of deflation. This was in the context of nations being reluctant to allow their pegged currencies to depreciate which would have provided in Keynes’ assessment high employment.

At the time Britain languished with high unemployment and Keynes began to articulate a view that not only was the reluctance to depreciate undermining employment growth but also that the government should use fiscal policy (via direct job creation in public works) to reduce unemployment.

I won’t consider in this blog the arguments that Milton Friedman (and the long line of Monetarists that followed him) made that the Tract was really the first Monetarist statement. That is a complex argument and I might write a separate blog on that as my own book project on that topic grows.

As Keynes’ view unfolded over the bleak 1920s in Britain he did argue that governments should run deficits when private spending declined and reduce those deficits when future growth was strong enough. The intent was that the budget was to be more or less balanced over the business cycle.

He never argued that governments should start cutting back deficits now and create surpluses just in case private spending growth is strong in the future. He readily understood how pro-cyclical policy would undermine private confidence.

In the context of today, with private spending still weak, notwithstanding some evidence that private investment might strengthen over the next few years, Keynes would worry about the negative consequences of a further weakening of aggregate demand and national income generation arising from a harsh fiscal contraction.

Further, in the context of the time, the classical economists (who Keynes’ discredited) advocated balanced budgets each year – the sort of rules that are now being discussed by conservatives.

So Keynes was reacting to that and noted that such a rule would be inflexible and damage the chances of the economy achieving full employment. His view was that budgets might be balanced over the business cycle if that was consistent with full employment.

He also favoured running balanced budgets on the recurrent (operational) budget – that is, consumption spending and allowing the capital works budget to vary over the cycle. This was consistent with his view that the principle fiscal intervention should come from regionally-targetted public works schemes aimed at maximising the employment dividend from the fiscal outlays.

The capital budget would be the vehicle for balancing over the cycle if that was appropriate. If you examine the current Australian government policy and its proposed fiscal retrenchment you will not see that sort of approach being adopted.

But Keynes would never has agreed to the blind administration of a fiscal rule of the type the Australian government or other governments are pursuing. He would never have agreed to “forward-looking” pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

Further, much of the smoothing out of demand over the cycle (which is really what the “balanced budget over the cycle” is about) was seen to come from the cyclical component of the budget. Governments around the world are manipulating the structural component to attack the cycle – that is the worst thing you can do.

The reality is that if we truly measured the current budget stance at a properly calibrated full capacity benchmark we would find the structural component is already close to balance and by the time the Government has finished its so-called Keynesian adjustments the budget will be very contractionary.

Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

Of-course, the “Keynesian position” is rejected by those who consider functional finance to be a better approach to fiscal management. Functional finance underpins Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

As I explained in this blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – the goal of fiscal policy is to ensure there is full employment. Whether that requires a deficit or a surplus in any particular period is neither here nor there.

The fact is that the budget outcome should never be the goal of policy. The goal should be to maximise real outcomes and maintain price stability. The problem is that in elevating the budget outcome to the centre stage and setting artificial rules, governments are very likely to damage prosperity.

They will typically also undermine the achievement of their own targets into the bargain because the fiscal austerity will reduce growth and the automatic stabilisers will take care of the rest!

It is a far better strategy to forget about the budget balance and concentrate on environmentally-sustainable growth and prosperity via well-paid employment.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow. My aim is to eliminate it and relax at the weekends – that will happen once everyone gets 5/5 and tells me they are bored!

Advertising Segment – Up coming music event

My old band – Pressure Drop – is making a comeback on March 24, 2012 in Melbourne. Here is a link to the announcement – Pressure Drop comeback show announced – March 24, 2012.

Here is another link about the show – Caravan Music Club Gig Poster released for circulation. The poster for the show is below – you can click it to maximise it. Tickets are on sale now.

For those interested, I am appearing on the 3PBS FM Reggae Show – Bablyon is Burning – tomorrow night (Saturday, March 10, 2012 – EAST at 18:00) and they stream all programs live via the Internet (you will see the Listen Live link on their home page). I will not be talking about budget deficits or government policy.

And here is a link to our latest video – Mother Earth and another video off our most recent CD – Peace Dub.

Excessive advertising fees were charged for this segment!

That is enough for today!

“This was consistent with his view that the principle fiscal intervention should come from regionally-targetted public works schemes aimed at maximising the employment dividend from the fiscal outlays.”

The problem with raking up Keynes is that he was speaking in the context of the time – and for the problems of the time.

Keynes is becoming a religious icon and his writings religious texts. That is bad news.

Even in the 1920s and 1930s ‘capital works’ required a lot of unskilled labour and few machines, and of course there are a lot of political brownie points in that sort of work. After all the car had barely got out of prototype at that point and we were still operating with steam engines.

Whereas of course today ‘capital works’ uses lots of highly sophisticated machinery and a smaller amount of very skilled and fairly skilled labour to operate them.

Therefore getting something of lasting value out of the efforts of unskilled labour is somewhat more difficult these days – particularly if you don’t see population expansion as lasting value 🙂

Did Keynes ever explicitly state that he was trying to get value out of unskilled labour, or can it only ever be an implicit assumption?

Neil,

He didn’t use exactly those words but I think it is clear from a number of examples he used that unskilled labor was part of his full employment agenda. There was a good bit of technical machinery in the ’30s with which he would have been familiar even if he wasn’t necessarily aware of all the uses to which it was put, such as at least one US corporation assisting the Nazis to locate members of their Jewish population.

I myself don’t see Keynes being invoked in a religious fashion. It seems to me that he is invoked because he is the most salient alternative to the present position. There are others from the past, however, who could also fill the role and who may be easier to read, like Robert Eisner, Robert Heilbroner, Nic Kaldor, and Hyman Minsky. But the public have generally never heard of them. So, what would be the point?

And I don’t see ‘raking up Keynes’ as necessarily a problem as long as we keep in mind that his book was imperfect, something he was well aware of. The UK government treated him as they did Turing, as a disposable ‘asset’. Marx wasn’t wholly right either but his socio-cultural analyis of the capitalist system was deeper than Smith’s and Smith is often invoked, incorrectly, as a supporter of the neoclassical position. I don’t see that using thinkers such as Marx and Keynes as shoulders to stand on, as it were, is necessarily a mistake given the proper provisos. And whether the times they wrote in are so different from ours that they have nothing to say to us is I think disputable.

“And whether the times they wrote in are so different from ours that they have nothing to say to us is I think disputable.”

Keynes obviously has much to add to the current debate and I don’t want to suggest an either/or rejection.

What I’m concerned about is using Keynes writings in a religious fashion – treating what he writes as unchallengeable, unchangeable wisdom.

I do see quite a lot of that around the blogosphere (but not here. Bill is always very careful to place Keynes in context of the time) – particularly when discussing capital works and ‘investment’ as against the job guarantee.

Neil Wilson: “Keynes is becoming a religious icon and his writings religious texts. That is bad news.”

Well, that is because the economic religionists regard Keynes as a dangerous heretic, right?

Neil, I agree with you that it is dangerous to consider what someone has written as a kind of sacred text, as happened for many years with Marx. Keynes certainly never treated his own work that way and, certainly, we shouldn’t. A major problem with Keynes is that so many secondary expositions distort what he wrote, such as his logical/mathematical views and their place in the General Theory. But that isn’t the only distortion. I feel that such distortions require one to go back to the original even if there is disagreement. And it has to be said that the original is difficult – it is not an ‘easy’ read, or clear and distinct, as he admitted himself. The history of distortions of Keynes’ views combined with the difficulty of his text may be playing a role in the kinds of positions taken by some commentators re Keynes’ work.