I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The myth of compassionate deficit reduction

I was going to write about last week’s ECB decision to purchase unlimited volumes of government debt which means that any private bond trader that tries to take a counter-position against any Eurozone government will lose. It means that the central bank can set yields at wherever it wants including zero. It means that all the mainstream economists are wrong if they claim that deficits drive up interest rates to the point that governments become insolvent because the private bond markets will refuse to purchase their debt. I will write about that tomorrow as I have some number crunching to do. But today – a related story – the myth that there is such a thing as a “good” budget deficit reduction when private spending is insufficient to maintain full employment. That should occupy us for a few thousand words.

In her New York Times article (September 8, 2012) – Cutting the Deficit, With Compassion – the former economics advisor to the Obama Administration Christina Romer attempts to outline a Democratic plan for “dealing with the deficit” which she says should be “front and center” and allow the Democrats to move beyond the defensive position of “criticizing the Romney-Ryan approach”.

To which any sensible person who understands these matters will ask – why should the Democrats want to “deal with the deficit” anyway? What exactly is there to deal with?

Well, Dr Romer thinks that the Democrats should be developing:

… compassionate deficit reduction. The essence is to cut the deficit in a way that does as little harm as possible to people, jobs and economic opportunity.

In other words, she is advocating that the Democrats should hold out to the American people a policy position that will undermine economic growth, condemn millions of them to entrenched unemployment, and reduce the future opportunities for American children to achieve to their potential.

Since when has that been a core Democrat principle in the US?

This article is an example of the latest ploy by those who want to maintain their membership of the “progressive club” but who also consider that the neo-liberal agenda about “fiscal consolidation” is the main game they want to be part of. The problem is that the two aims are not commensurate – in fact, they are diametric.

In my view, anyone who falls for the neo-liberal narrative about the need to cut budget deficits at a time when private spending is clearly inadequate to maintain full capacity growth voids their membership of the progressive club.

Dr Romer claims that the principle of “compassionate deficit reduction” is the centrepiece of the Obama policy agenda to retain office at the coming US Presidential election.

She wants the Democrats to embrace “it more explicitly …. and make it easier to explain to voters”.

Without considering how bad the alternative is in the US at present (Romney-Ryan), the fact that Mr Obama and his team are trapped in this sort of narrative and seek to refine it should disqualify him from retaining office. Governments are only worth electing if they can advance public purpose and help citizens improve their life outcomes.

A government that deliberately undermines those aspiration – and uses macroeconomic policy to impose constraints on individuals which mean they can never escape disadvantage does not deserve to remain in office.

It is a devil’s choice (the devil and the deep blue sea) – the rock or the hard place. But when the political process can only promote a degenerating convergence to an economic policy framework that is obviously destructive – then the citizens should find a new way of engaging with political parties and that requires them to reject both if they are simultaneously arguing for essentially the same thing.

Dr Romer thinks the US has some time to engage in deficit reduction because:

Investors are willing to lend to the United States at the lowest interest rates in our history. That gives us the ability to cut the deficit on our own timetable. We should pass a comprehensive, aggressive deficit reduction plan as soon as possible, but the actual spending cuts and tax increases should be phased in as the economy recovers.

Why even invoke the notion that bond markets have the power to determine the course of fiscal policy? That is one of the starting point neo-liberal myths. The bond markets are more like mendicants seeking their handout of risk-free annuity income.

Even the ECB has demonstrated that the currency issuer runs the show whenever they choose to exercise that unique capacity. There is no imperative to reduce deficits in the fear that the private “investors” will impose some toll by refusing to buy the debt.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

Which means that a “comprehensive, aggressive deficit reduction plan” would only be indicated for the US government if the following circumstances were coincident:

1. All labour and capital resources were being full utilised.

2. The economy was thus producing at potential.

3. That demand-pull inflation (nominal spending outstripping the real capacity to produce) was rising rapidly.

If those conditions are absent then there is a need for a deficit expansion plan rather than the alternative which Dr Romer is advocating.

She knows that “immediate, extreme austerity would plunge … [the US] … back into recession” and that that is is obvious that a:

… fiscal contraction … would cause a rapid rise in unemployment. Well, duh.

If the “rule of thumb is that every $100 billion of deficit reduction will cost close to a million jobs in the near term” is true (and certainly the direction of the relationship is correct if not the quantum) then any deficit reduction will undermine employment – in the short-run.

So you would only consider a deficit reduction if there was credible evidence that there were substitutes in the wings ready to fill the gap.

Dr Romer provides no evidence that personal consumption, private investment and/or net exports will be able to not only offset the lost public contribution to aggregate demand caused by the deficit reduction but also significantly add to overall spending so the economy can reach full capacity in the near future.

It is almost as if she operates in some sort of parallel universe – Yes, deficit reduction is damaging. But, we can do it nicely – is the message she wants to provide. But there is nothing nice about deliberately causing unemployment.

Consistent with these sort of articles that essentially advocate deficit reduction but claim that it can be done nicely, Dr Romer argues that a change in the composition of the budget can help reduce the damage.

She wants the US government to:

… pair serious long-run deficit reduction measures with equally serious, near-term jobs measures – like a sizable short-run infrastructure program and a one-year continuation of the payroll tax cut for working families first passed in 2010 … Even better would be to give businesses increasing employment a tax credit so large they couldn’t help but notice it, and state and local governments a round of aid generous enough to finally stop the hemorrhaging of teacher jobs and essential government services.

A second feature of compassionate deficit reduction is well-designed tax reform that raises at least some additional revenue.

The message gets confusing. Overall, a change in the composition of the Budget spending initiatives might be warranted to ensure that public spending is jobs-rich and promotes equity. At any point in the business cycle these concerns should be monitored to make sure public spending is actually advancing desirable outcomes in addition to ensuring there is “enough” aggregate spending.

But the composition of the budget is one thing and the overall impact on aggregate spending is another. The macroeconomics imperative is to ensure that the economy is moving towards and achieving full employment.

Changing the composition of spending at the same time as cutting overall net public spending may redistribute the spatial and personal costs in desirable ways but the strategy will still cause unemployment and lost national income and undermine future capacity.

The question that Dr Romer avoids is whether now is the time to be cutting net spending. All she asserts (more than once) is that the the US “budget problems are so large” – but never articulates what the actual problems are.

By avoiding a discussion of the basic premise she falls prey to the neo-liberal line, which is really about reducing the size and spread of the government sector rather than about any intrinsic reality that the US government is in danger of becoming insolvent. They claim the latter but really just want the former.

Dr Romer falls into that narrative trap and, in doing so, undermines the credibility of her “progressive” position and makes it easier for the neo-liberals to maintain the dominant position in the public debate.

Dr Romer also focuses on the question of “inefficiency” of public spending. Again there is a conflation here between composition and level. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not advocating “wasting” public spending – by which I mean using public spending to command access to real resources and then using more real resources than are necessary to accomplish the particular task in question.

She says that it is fortunate for Democrats that:

… there is much inefficiency in the current system, so it should be possible to cut costs without lowering benefits. But if we can’t save enough money by reducing waste and finding better ways to provide care, we might have to consider more painful choices.

But while the spending might be considered “wasteful” from a microeconomic (resource usage) perspective, the fact is that the spending goes into the expenditure system and drives firms to provide output and employ people. It might be that some firm or another is supplying more output than is strictly necessary to fulfill a particular real aim.

But if you cut that spending and get better micro efficiency, you still have the macroeconomic problem to address – which is to ensure that total spending is commensurate with the level necessary to absorb all the workers that wish to work at the current wage levels.

Cutting spending to improve resource usage in the health system, for example, while desirable if there is waste, will mean firms will lay off workers in that are of activity. That means that spending elsewhere is required to ensure those workers are redeployed into other uses.

Deficit reduction prevents that sort of redeployment. The government might achieve a “leaner” economy with higher micro efficiency but it will be at the expense of increased macroeconomic inefficiency courtesy of the rise in mass unemployment.

The latter imposes massive costs on an economy (which are disproportionately borne by the weak and low-skilled) which dwarf the known and estimated costs of so-called microeconomic inefficiencies. A focus on the latter should never be pursued at the expense of the former.

It is also easier for an economy to transition from states of micro inefficiency. which require structural reforms, when it is in a state of high employment rather than when it is entrenched in a state of high and persistent unemployment and governments are running pro-cyclical fiscal austerity strategies – no matter how compassionate the deficit reduction is.

How close is the US to the three circumstances I outlined above? Answer: not very close at all.

The most recent data available from the US Congressional Budget Office – Deficit or Surplus With and Without Automatic Stabilizers – (January 31, 2012) estimates the extent of the macroeconomic inefficiency in the US at present.

The CBO define potential GDP as “the quantity of output that corresponds to a high rate of use of labor and capital” and the GDP gap “equals GDP minus potential GDP”, which is the quantity of output that corresponds to a high rate of use of labor and capital”

The “unemployment gap equals the rate of unemployment minus the natural rate of unemployment, which is the rate of unemployment arising from all sources except fluctuations in aggregate demand”.

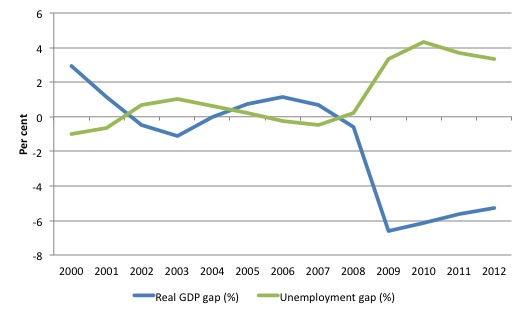

The following graph shows the GDP and unemployment gaps (which are by dint of the way they are constructed near-mirror images of each other). The values for 2011 and 2012 are “Projected using CBO’s baseline assumptions”.

I caution readers who seek to use this data. As I explain in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – the estimates of the GDP and unemployment gaps provided by the CBO are likely to be an understatement of the true gaps.

The techniques that organisations such as the IMF, OECD and CBO use to estimate both potential GDP and the “natural rate of unemployment” are biased towards under-estimating potential GDP and over-estimating the “full employment” unemployment rate – which they call the natural rate as a reflection of their ideological adherence to the mainstream macroeconomic liturgy.

But even if we accept the CBO estimates of each gap – each macroeconomic inefficiency – for the sake of comparison, the average real GDP gap (even with the earlier and sometimes severe recessions included) for the period 1962 to 2007 was -0.3 per cent – that is, relatively small. By comparison the gap between 2008 and 2011 averaged 6.2 per cent – that is, relatively huge.

CBO currently estimate the real GDP gap to be around 5.3 per cent and the unemployment gap to be around 3.3 per cent.

The daily loss of income that is occurring in the US as a result of these gaps is enormous. This lost income will never be regained. It is lost forever.

I also note that inflation is hardly an issue in the US at present.

So why would any progressive want to buy into the neo-liberal deficit reduction narrative?

Further, growth is now slowing which will mean these CBO estimates of the GDP and unemployment gaps will be conservative (quite apart from the technical points noted above about bias).

The latest US national accounts data for the second quarter 2012 was published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis – on September 4, 2012.

It shows that the US economy slowed from 2.0 per cent in the March quarter to 1.7 per cent in the second-quarter 2012. These estimates – the so-called “second estimates” are based on more comprehensive data and revised the growth estimate for the June quarter up from 1.5 per cent.

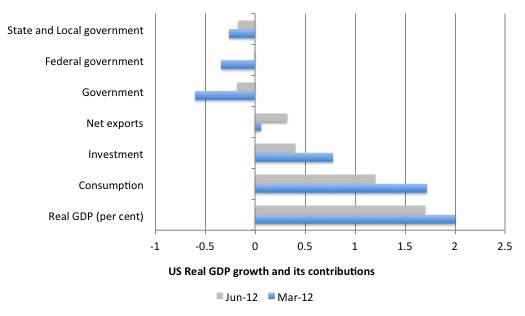

The following graph shows Real GDP growth (per cent per annum) and the respective contributions to that growth from the main expenditure components (percentage points annualised) for the March-quarter and June-quarter 2012.

You can see that the contribution of government was negative in both quarters but less negative in the June quarter 2012.

The BEA say that:

The deceleration in real GDP in the second quarter primarily reflected decelerations in PCE, in nonresidential fixed investment, and in residential fixed investment that were partly offset by a smaller decrease in federal government spending, an acceleration in exports, and a smaller decrease in private inventory investment.

PCE is personal consumption expenditure.

Conclusion

My reading of the latest data from the US – both the labour force and national accounts data – is that the policy reality is the opposite to that held out by Dr Romer. She is making a political statement disguised as an economic imperative.

In my view, political leadership is about taking the economic imperative and ensuring the public understand the correct policy settings consistent with that imperative.

The economic imperative is clear. There is an urgent need for more discretionary net spending in the US which should certainly be targetted to ensuring it is jobs rich.

Growth is slowing and a public stimulus is required. There is no way under present circumstances that private spending (or net exports) will be sufficient to push the growth rate towards its full employment level while also compensating for the negative contribution from the government sector. To further strain demand by deliberate deficit reduction is equivalent to madness.

If the GDP and employment gaps can be reduced and close back to the long-term average, then the revenue side of the US budget will increase dramatically (relative to now) and get back towards the 18 per cent of GDP mark. The deficit terrorists have been trying to argue that since 2000 the revenue side of the US budget has been “structurally weakened” by tax cuts. The average between 2000 and 2008 was 17.9 per cent of GDP, not that much below the long-term average. So the structural deterioration argument doesn’t hold.

Budget deficits are required whenever there is a non-government spending gap. That will always be the case if the non-government sector desires to save overall.

This MMT insight should be the basis of a progressive attack on the orthodoxy not half-baked feel-good notions of compassion deficit reductions which really amount to the deliberate creation of joblessness.

There is no inevitability that inflation will result if governments maintain high levels of demand and support private consumption. The trick is to understand that the deficits are also supporting net private saving (the other side of the consumption coin). Deficits beyond that support level do introduce inflation risk. But then who advocates that?

Progressiveness

As an aside, after my talk in Brussels last week I received a fair share of “hate E-mails” and (deleted) comments on my blog from people purporting to be representing the “progressive left” – more or less accusing me of being some ill-formed C18th conservative Tory for advocating that the government should guarantee employment. Apparently, those who haven’t read any of my work on the topic think I am advocating a return to the poor houses – a form of institutionalised slavery.

Ignorance is bliss for these E-mail senders.

The point of the Job Guarantee is that is the base case safety net. It doesn’t aspire to cure all ills. It doesn’t replace the need for expanded government investment in public infrastructure (and the related skilled jobs that would accompany that) or the creation of adequate numbers of skilled public sector jobs in the service-delivery areas (education, health, environment, arts and recreation etc).

It just ensures that there is enough interesting work available at all times to anyone who cannot find work elsewhere (for whatever reason).

They claim that expansionary fiscal policy can always create full employment – which is correct. But it cannot always create full employment and price stability, which are the two key macroeconomic goals in a mixed economy.

Further, an economy that is enduring accelerating inflation will ultimately become unsustainable and governments will invoke contractionary policy and the full employment status will lapse.

The Job Guarantee approach – relying on employment buffer stocks – is the way to defeat that trade-off. It means that the most disadvantaged workers can always access work. Surveys show that the unemployed prefer to work than being marginalised on social security systems, which have increasingly become punitive.

Why the Job Guarantee proposal offends those who claim to be progressive is beyond me.

Yes, it is a palliative to the “capitalist hegemony” and doesn’t advocate a violent revolution to overthrow the filthy exploiting capitalist power brokers. When the time is right to abandon the capitalist system in favour of a more functional and equitable system that safeguards human potential and our natural environment then I will be one of the first to the barricades (although I suspect my knees will have given in long before that time arrives!).

But until that time I prefer to use my academic position (relatively well-paid and somewhat secure) to advocate policies that will make a real difference now. I prefer not to use my secure position to drink latte in cafes in an assembly of self-styled progressives and discuss how the revolution will pan out while ignoring the every day reality that people want work and do not have it and are poor and socially excluded as a consequence.

I prefer not to condemn the unemployed to years of this sort of macroeconomic tyranny while I wax lyrical about post-modern interpretations of what Marx said and how it relates to the struggle towards revolution.

When I receive E-mails (or comments on the blog) which attack the Job Guarantee as a fascist or Tory plot and the correspondents claim they represent the true progressive position and tell me that I am a progressive quisling – I think about the 1971 poem/song – The Revolution Will Not Be Televised – by Gil Scott-Heron. The lyrics contain the following refrain:

The revolution will not be televised, will not be televised,

will not be televised, will not be televised.

The revolution will be no re-run brothers;

The revolution will be live.

I also think about the more recent song from the – Brooklyn Funk Essentials – The Revolution was Postponed because of Rain. It is a very stark commentary on the so-called progressive side of the political struggle. You can see the full lyrics at this blog from 2010 – A new progressive agenda?.

I am currently in Maastricht (at the University) until the coming Thursday. Then I will be in London until next Monday (from Thursday afternoon). So the times that I publish my blog will remain atypical until then.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Why the Job Guarantee proposal offends those who claim to be progressive is beyond me.”

I don’t understand it either. But one thing is certain, if MMT proposals annoy the rabid left and the rabid right in equal measure then they are very likely to be somewhere near correct.

Hi Bill,

Sorry, this question is unrelated to the article.

What do you think the costs and benefits of inflation are?

Would you advocate a specific inflation target? If so, what would it be? (0%, 2%, 4%, 10%, etc)

Thanks.

“Why the Job Guarantee proposal offends those who claim to be progressive is beyond me.”

Well, there is the basic injustice that the population has been driven into debt with its own stolen purchasing power via credit creation. Since there is about an $8.5 trillion difference between US bank reserves and US bank deposits then a ban on further credit creation would allow $8.5 trillion to be metered out to the entire US population until all deposits were backed 100% by reserves. The metering rate would be such that the new reserves would replace existing credit as it is paid off for no net change in the total money supply (reserves + credit).

Do you think $8.5 trillion in inflation-free stimulus might end the Depression in the US?

As for ending capitalism, it’s really just the money system that needs reform.

But in any case, I’ll always appreciate you Bill for [paraphrase] “borrowing by a monetary sovereign equals ‘corporate welfare’ .” Slam!

Best wishes.

If new money was just handed out to the population equally, then no complaint about the size or efficiency of government could be made. How many conservatives dared complain about G.W. Bush’s stimulus checks? Who will dare say to a voter “You’re not smart enough to spend that money wisely” (except Progressives? 🙂 ).

No doubt much of this comes from the quadrennial emergence of our “political progressives”, progressives in name only who act as the Democratic Party’s right wing orthodoxy enforcers. In this outing of the group, their goal is to beat up any full time progressives who dare to suggest something as progressive if Obama is either (a) not already doing it, or is (b) not already promising to do it. Anyone falling afoul of this orthodoxy is summarily catcalled as “might as well be voting for Mitt Romney”. [See also, “Brownshirts”.]

Christina Romer was the only person in the Obama administration to argue that deficit spending of 2-3 trillion would be necessary.

Obama may be a disappointment, but Romney does not take orders from Wall Street Vultures, he is one.

I think one concern I have with basically ignoring the deficit, is that if we do enter a period of ‘demand-pull inflation’, then as I understand it, an MMT remedy would involve cutting government spending or raising taxes. I’m not sure how easy it would be politically to raise taxes in a strong inflationary environment. I suppose the classic response of raising interest rates might be enough?

What is the appropriate response to ‘demand-pull inflation’? Or, is there no real belief that it will happen?

What is the appropriate response to ‘demand-pull inflation’? SteveK9

Since “bank loans create deposits” then “bank loan repayment destroys deposits” so the commercial banking system is potentially a great engine for reducing the money supply by simply raising reserve requirements and not allowing the Fed to provide new reserves.

@SteveK9

The stabilizers in budgets should in theory handle most of a demand-pull inflationary event. Government spending falls as private spending rises (fewer welfare payments due to increased employment) and revenues rise as economic activity generates more tax receipts. Should the economy become red-hot the budget will be pushed into surplus and automatically begin to drain the private sector’s net financial assets. This is what actually drove the Clinton surpluses, except the money was coming from accelerating debt levels in the household sub-sector and wasn’t sustainable.

except the money was coming from accelerating debt levels in the household sub-sector and wasn’t sustainable. Ben Johannson

So some deficit spending is always advisable so accelerating debt to pay the interest on previous debt won’t be necessary?

@F. Beard

Deficits don’t come from debt, they come from crediting accounts and creating new, permanent net financial assets. Nor do the yields paid on bonds require the government sector go into any form of debt.

@Ben Johannson,

I was talking about preventing the need for accelerating private sector debt. If the government does not provide the interest for private debt via deficit spending then where else can it come from?

@ Ben Johannson & SteveK9: Yes, & the JG will be the King of the Automatic Stabilizers. Generally achieving a zero employment, low or zero inflation economy.

The sensible thing is to always look at what the government does with the money it spends, not how much. That’s like a general worrying about how many orders he & his officers are issuing, rather than their effect on the battle.

“Why the Job Guarantee proposal offends those who claim to be progressive is beyond me.”

I’m not sure if there is one sole reason for it offending those who consider themselves progressives, I think some don’t like the idea of a job guarantee because there seems to be an element of force in it, like someone being threatened with the removal of benefits if they don’t do as they’re told, which is similar to the way benefits work now, only now the money being given to people is a pittance and they’re being forced to go to these ridiculous job courses that help no one but the con men running them. I just think the idea of force turns some people off.

Beard, Johannson: Good points, thanks. Beard, I did mention raising interest rates, which is another way of reigning in the private banking sector. Maybe these would do the job without more politically unpalatable approaches.

Some Guy: I would like to see a JG, but frankly am pessimistic that it will be possible any time in the near future … at least in the US. We need to make progress on concepts that are easier to sell first. Just getting back to old-style Keynes would be a big move forward. Right now, as this article describes, even ‘progressives’ have a way to go. Christina Romer is probably one of the most reasonable economists of influence we have … and Bill is ripping into her.

On the JG, Dean Baker wrote an article for the Guardian titled: ‘Poverty: The New Growth Industry in America’. I sent him a note and asked what he thought of the JG proposal from W. Mosler, W. Mitchell, R. Wray, etc.? He did send a note back and expressed that he thought it would take 10-20 years under the best circumstances to get a program in the US. No reason not to keep promoting the idea though, or it will never happen at all.

I did mention raising interest rates, which is another way of reigning in the private banking sector. SteveK9

Is it? What does it matter what interest rates are if asset prices are rising faster? If I can borrow at 25% to buy an asset that is appreciating at 30% then why not?

So actual hard limits on money creation are needed, imo.

“If the government does not provide the interest for private debt via deficit spending then where else can it come from?”

It comes from the flow. Interest is £/month and is a flow payment. Debt is £ and is a stock. Different units. Compare them and you are comparing apples and oranges.

Interest is paid from turnover like dividends. It is merely a share of the profit share to other capital contributors.

£100 of capital stock generates many £100s of sales turnover/year.

It comes from the flow. Neil Wilson

Since all money is typically earning interest else it is “not being put to work” then an external source of interest is needed that is not lent into existence else the debt must accelerate. That’s why we need deficit spending by the monetary sovereign without borrowing.

Neil,

Since credit only creates the dollar balances necessary to satisfy the principal payments, accrued interest is in excess of the money creation.

The balances necessary to pay the interest accrue at the rate of compound interest and the funds required to satify those balances don’t exist. It’s a closed system wrt net dollar balances. The only possible source of the interest balances is net government spending.

The liabilities accruing from interest will eventually seize the system if not offset by net creation of funds by deficit spending because borrowers will not be able to acquire the dollars necessary to make the interest payments (they don’t exist) leading to mass default.

This dynamic is magnified by the accrual of saving balances. Saving in this context is defined as dollars removed from the pool of funds available for spending.

F. Beard, the Central Bank does not destroy the money it receives as interest; it reports it (minus costs) as profit which then gets paid to the government, in a similar way to how commercial banks pay dividends to their shareholders.

the Central Bank does not destroy the money it receives as interest; it reports it (minus costs) as profit which then gets paid to the government, Aidan

After which we can count on the Federal Government to spend it* into the economy again.

in a similar way to how commercial banks pay dividends to their shareholders. Aidan

Not quite since the shareholders cannot be counted on not to lend out some of the dividends they receive. So then where does the interest for the lent out dividends come from?

*Ignoring that reserves paid to the Federal Government cease to exist since the the Federal Government can recreate them by spending new reserves into existence to take their place.

F. Beard, you’re missing the most important point: interest doesn’t take money out of the economy. Governments rightly regard Central Bank revenue the same way as tax revenue: spending it does not count as deficit spending.

The interest from the lent out dividends comes from whoever they lend it to, who get the money from whoever they work for/sell stuff to. Either way it does not necessarily require more money to be in the economy.

My argument does not depend on interest leaving the economy; it depends on the fact that almost all money in the private sector spends its time in interest bearing accounts. Even when money is spent it moves from one interest paying account to another interest paying account. Where then does the interest come from?

My concern is that the same clowns administering work for the dole and other such schemes would be in charge of running the jobs guarentee.

However, if those involved with administering work for the dole and / or similar schemes were banned from such roles with the JG then I’d sleep a lot easier.

“The balances necessary to pay the interest accrue at the rate of compound interest and the funds required to satify those balances don’t exist. ”

Yes it does. You are confusing stocks and flows.

Steve Keen has a dynamic model in place that demonstrates that the circuit functions quite happily with a set stock of debt circulating. Go run it up on a computer and watch it.

Interest is a charge of money over time. Therefore it has to be compared to the economy’s turnover which is also money over time not its capital stock

The value to pay interest on a loan comes from the same place that the value to pay dividends come from – the leverage of a set amount of capital stock into a larger multiple of money over time – which is called the stock turn – or turnover.

“Why the Job Guarantee proposal offends those who claim to be progressive is beyond me.”

To be fair, I think it’s possible to imagine a JG system being abused if the wage offered is very low, or if the jobs programs are badly designed and offer low quality, or even punitive forms of work. I know that’s not a necessary outcome of the JG and certainly isn’t remotely what you advocate, but I think that even when the JG idea is broadly accepted and implemented there is likely to be pressure from vested interests to push the scheme in that direction. Full employment obviously enhances the bargaining power of labour and a successful *public* employment program that achieved full employment and was recognised by citizens as adding real value to society would be a worrying precedent to elites. Which is all the more reason to fight for one.

There is no place in our monetary system where money just floats and never goes out. Receivers of interest income will spend it, it is that simple. At any given time money stocks in the economy represent monetary saving desires of the population. That much is stored away for the purpose of future spending. Change in saving desires means government has to accomodate to sustain full employment. But saving desires could also be changing downwards, as happened during housing bubble. Then, increased value of the houses diminished desire to have monetary savings, and households started to spend more than their income drawing down savings.

“Yes it does. You are confusing stocks and flows.

Steve Keen has a dynamic model in place that demonstrates that the circuit functions quite happily with a set stock of debt circulating. Go run it up on a computer and watch it.”

Neil, I respectfully disagree. This is not a stock/flow issue, it’s a stock/stock issue.

My view is strictly from system mathematics, the non-government is a closed system wrt dollars and the number of discrete elements is fixed ie it cannot be changed without external intervention.

1. Assume the system has some number n discrete elements (dollar assets na) created through credit.

2. It follows that the system also contains n discrete liabilities in dollars (nl). na + nl = 0

3. Interest accruing is a net add of dollar liabilities that can only come from a source external to the system. The closed system now contains more liabilities than assets. na + ni = an increasing negative number.

4. Therefore there is no longer a balance in the system, liabilities exceed assets, the system has negative net value wrt NFA’s.

5. Further issuance of credit to attempt to satisfy the interest payments increases the ratio of liabilities to assets, which will eventually lead to instability at the point where credit can no longer be expanded ie debt service reaching a level greater than the income available to pay it. This is a soft ceiling because of the complex dynamics involved but the path of instability is clear.

Interest must be a direct add (no liabilities) to maintain at least a balance between dollar assets and liabilities.

You are welcome to try to correct my math.

I admire Steve Keen and his work but if his model shows this is a sustainable process he has made a mistake somewhere. I am pretty confident he can’t construct a model that violates the laws of arithmetic wrt closed systems.

@paul: You are forgetting that interest is added both on the asset and on the liability side. Of course, there are different ways to model this, but here’s a simplistic scenario: A has a loan at bank B, i.e. A has 100# liabilities towards B, B has 100# assets/claims on A. Now interest is calculated, say 5%. A now has 105# liabilties, B has 105# assets (the claim on A has gotten larger at the same time).

When it is time to actually pay the interest (assuming no reduction in the principal), A will have 105# liabilities towards B, plus 5# of assets gotten from someone else (income/revenue paid by C). Then A hands those 5# over to B. Now A’s liabilities are again 100#, and B’s assets are 100# claims on A plus the 5# handed over. Over time, B will spend those 5#, possibly paying them out to C; now C can pay again to A, and that’s how the cycle closes.

Basically, if you believe that assets != liabilities at any point, you are forgetting some interest payment somewhere. Most of the time, people forget the payments made by banks to their shareholders and employees, and the “payment” made by the central bank to the government.

but if his model shows this is a sustainable process he has made a mistake somewhere. paul

Steve Keen does say the system need accelerating debt to keep going but then says that nothing can accelerate forever. So Keen is not saying the system is stable.

Over time, B will spend those 5#, possibly paying them out to C; now C can pay again to A, and that’s how the cycle closes. Nicolai Hähnle

Only if none of the 5# is stored in an interest paying account. How likely is that?

Actually, our money system is worse than a gold standard wrt interest since there is at least some hope of mining the interest required under a gold standard.

I think the point stands that deficit spending by the monetary sovereign is necessary so aggregate interest can be paid. And this is a problem for MMT supporters how? In favour of balanced budgets are we?

You are forgetting that interest is added both on the asset and on the liability side. Nicolai Hähnle

That’s irrelevant if the interest does not even exist in aggregate.

One can add unicorns to both sides of a balance sheet and yes it will still balance but so what?

“My view is strictly from system mathematics, the non-government is a closed system wrt dollars and the number of discrete elements is fixed ie it cannot be changed without external intervention”

It may very well be but that is represented by a set of assets and a set of liabilities and the circulation flow of both of them is different.

So I’m afraid you are incorrect. The dynamic flow shows a stable system.

And until you introduce the time element into your model you won’t see how it works. You need to model through time.

A flat static model leads you to the wrong conclusion.

Receivers of interest income will spend it, it is that simple. Hepion

No it isn’t. Some of that interest may be lent for additional interest and the interest earned on that for additional interest and so forth.

The attempts to just usury here are amazing. But in any case, why should we all have to work for the money creators/lenders? And hope that they consume (spend) enough so we can pay them their usury? Isn’t that pathetic?

“Some of that interest may be lent for additional interest and the interest earned on that for additional interest and so forth.”

That’s what capital ratios are there for. They limit lending. Perhaps it might be better to set a maximum loan book size for a lending institution.

“And hope that they consume (spend) enough so we can pay them their usury? ”

That applies to any savers – not just bank investors.

Perhaps it might be better to set a maximum loan book size for a lending institution. Neil Wilson

How about we eliminate all government privileges for the banks such as deposit insurance and a legal tender lender of last resort and let the banks extend credit (and create other money forms) at their own risk and at the risk of such depositors as are willing to bear it?

As for the needs of the general population, the monetary sovereign itself should provide a free (up to normal household limits) risk-free fiat storage and transaction service that makes no loans and pays no interest.

We need to separate risk-free fiat storage and transaction services from lending and credit creation which are inherently risky.

We need to separate risk-free fiat storage and transaction services from lending and credit creation which are inherently risky. FB

And inherently discriminatory. Both lending and especially credit creation are discriminatory. Why should government subsidize discrimination?

That applies to any savers – not just bank investors. Neil Wilson

Common stock as a private money form has some interesting properties. It is not lent into existence; it is spent into existence. And it is democratic too. On one hand a stock holder might vote against issuing new shares (spending) to avoid diluting his shares. OTOH, he might vote to issue new shares so as to increase the eventual value of his shares. But in either case, the decision is democratic and the disgruntled may sell their shares if unsatisfied. Isn’t this the way private money should be implemented instead of a single government enforced monopoly money supply for private debts?

“We need to separate risk-free fiat storage and transaction services from lending and credit creation which are inherently risky.”

You might. We already have that in the UK. It’s called National Savings.

But you still have government deposit insurance and a legal tender lender of last resort (the BoE). Why is that?

“And until you introduce the time element into your model you won’t see how it works. You need to model through time.”

“A flat static model leads you to the wrong conclusion”

Neil, I hate disagreeing with you because genarally I’m 100% in agreement with what you write. Not in this case however.

I’m well aware of the time element (delay, phase shift, whatever you want to call it) but that does nothing to alleviate the accumulating liabilities so your model must assume that credit can be expanded without constraint, and ignores saving, which is the biggest elephant in the room.

Further, I am not viewing this in a static state. I’m an engineer, few problems are static. Give me some credit.

One can’t deny that in a credit-only circuit liabilities accrue as negative net financial assets over time. No other scenario is possible in a closed system. The system is allowing an injection of negative net financila assets from an external source by design. No amount of credit expansion can undo this dynamic mathematically.

You aren’t making that claim are you?

The question then becomes over what time period will the liabilities become a problem, time as an inverse function of interest rates. In a perfect non-leakage world this timespan may be so long as not be a problem, I haven’t tried to figure out how far in the future that may be.

What I do know intuitively is that once leakages such as saving enters the picture the time element becomes more immediate and problematic.

How soon? Current conditions have answered that question, The question that remains now is how long will it take for the system to right itself.

Even Steve Keen knows that the system will not fix itself and further extension of credit is not a solution nor is it even possible.

Steve’s solution is some sort of a debt jubilee, which is functionally equivalent to fiscal expansion albeit after-the-fact. The money has already been spent. Of course further deficit spending properly targeted can also provide relief.

It is clear though that a credit-only circuit is a bad idea for many reasons. Especially one that relies on credit for the expansion of sales for consumer goods.

What I do know intuitively is that once leakages such as saving enters the picture the time element becomes more immediate and problematic. paul

Certainly this would be a problem if people used the mattress (hoarding). But by “saving”, do you mean the difference between old loan repayment and new loan creation?

Steve’s solution is some sort of a debt jubilee, which is functionally equivalent to fiscal expansion albeit after-the-fact. paul

Actually, Steve’s solution is a universal bailout, including non-debtors, with new reserves. He says it should be about 50% of GDP.

The money has already been spent. paul

Banks don’t actually lend reserves except among themselves so what has been spent is “bank money”, so-called “credit.” This gives us a one-time opportunity to bailout the population with new reserves without increasing the money supply IF we required 100% reserves for new lending and if the bailout is metered to just replace credit as it is repaid. Then the new reserves as they are paid to the bank to extinguish debt simply go to backing deposits until they are 100% backed.

paul –

One the contrary, if the system is closed then it is impossible for that to happen. Let’s look again at the system:

So far so good.

WRONG!

The people paying the interest and the people receiving the interest are both within the system.

Therefore it still adds up to zero.

There are often good reasons to increase the money supply, but liabilities inevitably becoming a problem is not one of them.

@F. Beard, “Only if none of the 5# is stored in an interest paying account. How likely is that?”

Are you referring to the possibility that somebody along the way saves (part of) those 5#, i.e. a “leak” in spending? That is of course a possibility. But even in that case, the sum of assets remains equal to the sum of liabilities. I was specifically trying to explain this to paul, who believes that – because of interest – the sum of liabilities can become larger than the sum of assets. I was assuming this kind of cyclical payments to illustrate how interest can work even with a stable sum of assets and liabilities. This assumption doesn’t necessarily hold, but that’s unrelated to the problem we were talking about (if people do save, you need increasing assets and liabilities to avoid default, but the sum of assets will still be always equal to the sum of liabilities).

“One can’t deny that in a credit-only circuit liabilities accrue as negative net financial assets over time”

I can and I do.

The delta over a time period is this:

– Bank charges interest via their limited seigniorage (DR Loans, CR Bank Equity)

– Bank pays staff and investors (DR Bank Equity, CR Bank ‘wages’)

– Bank staff and investors buy stuff (DR Bank ‘wages’, CR ‘Firm Income’)

– Firm pays interest (DR Firm Income, CR Loans).

So when a bank charges interest it creates the means by which that interest is paid, and a side effect of that is that real stuff is created and transferred.

You effectively get the same cycle in the government sector

Government creates tax liability (DR Tax Due, CR Tax Income)

Government pays staff (DR Tax Income, CR Staff Wages)

Staff buy stuff (DR Staff Wages, CR Firm Income)

Firm pays taxes (DR Firm Income, CR Tax Due)

The government creating the tax liabilities makes the means by which the tax is paid and the side effect of that is that real stuff is created and transferred.

Any effect that believe you are seeing is merely a result of savings desires – people not spending all their interest income and that not being offset by other people borrowing. But that’s the same as saving any other type of income, Employment, Property, or dividends.

Which leads to the core MMT message – the government sector has to offset the excess net-savings desires of the non-government sector or you get a depression. It will not clear by itself.

Are you referring to the possibility that somebody along the way saves (part of) those 5#, i.e. a “leak” in spending? Nicolai Hähnle

No because except for actual physical cash I don’t see how there can be any leaks (assuming an international banking system).

My point is a different one. Assume a fixed money supply where all money is in interest paying accounts except for brief transaction periods. Where is the interest to come from?

Of course our money supply is not fixed and the banks can lend the required interest into existence. However, the banks require extensive government privileges such as deposit insurance and a legal tender lender of last resort in order to create much credit which is very problematic from a free market perspective.

So then if government privileges for the banks were removed (as they should be) then some deficit spending by the monetary sovereign would be necessary so that interest in aggregate could be paid.

No because except for actual physical cash I don’t see how there can be any leaks (assuming an international banking system). FB

Except for a budget surplus by the monetary sovereign or an excess of credit repayment over credit creation.

You effectively get the same cycle in the government sector Neil Wilson

It’s a given (and Biblical) that government may tax us. But why are the banks allowed to do so too via extensive government privileges such as deposit insurance, a legal tender lender of last resort and legal tender laws for private debt?

“Assume a fixed money supply where all money is in interest paying accounts except for brief transaction periods. Where is the interest to come from?”

If you assume that then you need to move to Mars where they may have that system.

Here on Earth money is endogenous and is dynamically created and destroyed at the current price of money.

Here on Earth money is endogenous and is dynamically created Neil Wilson

By a government backed/enforced usury for stolen purchasing power cartel. Quite an oddity for a so-called free market, wot? And one that was a major cause of WWII the last time it wrecked the economy.

But press on. Central banking is only 324 years old. A few more centuries and a few more heaps of corpses should do the trick.

@F.Beard: “My point is a different one. Assume a fixed money supply where all money is in interest paying accounts except for brief transaction periods. Where is the interest to come from?”

Even in such a truly mythical world there need not be a problem (unless people save in the sense that they cause a leak in the spending cycle, i.e. they leave their money in a bank account without spending it to pay others – this is the exception that I mentioned in my earlier comment). Let me illustrate how such a mythical world can work out.

Since you posit a fixed money supply and interest paying accounts, I assume that in your world, there is a fixed amount of debt D that non-bank actors owe the banks, and a corresponding fixed amount M of money on bank accounts. Assume that money is _always_ in bank accounts (it is instantaneously transferred – this is even stronger than what you asked for). [D = M must be the case for this system to make sense, because all debt towards banks has corresponding claims on banks, i.e. money-ish things]

Let us further assume that interest payment works as follows: at a predetermined time every year, the banks deduct the interest from the bank accounts of everybody who has debt, and they add the interest to everybody with a bank account. This all happens instantaneously. I hope you can agree with this mode of interest payments.

Obviously, the total sum of all interest paid by the bank cannot be larger than the total sum of all interest taken by the bank (otherwise, the bank would operate at a loss). In practice, the interest paid by the bank will be strictly smaller than the interest taken, so that the bank makes a profit. This profit is then added to somebody’s bank account.

In any case, there are some people who have bank debt, and therefore must have enough money on their bank accounts at the fixed point in time when the interest payments / redistributions happen.

Throughout the rest of the year, people work and trade, and there are corresponding flows of money strictly between people’s bank accounts.

All that has to happen for the model outlined so far to continue in a stable way indefinitely is that in net terms, the people who receive interest (or profit, or salary) payments from the bank pay all the interest received over the course of the year to the people who have to pay interest because they have debt. This would mean that those who are in debt have to work more indefinitely, to offer the real goods and services that others by from them. But there is nothing inherent about interest that necessarily causes a problem.

In practice, of course some of the people who receive interest payments will save that money in the sense that they simply leave it in their bank accounts without using the money to buy anything. Then money will accumulate in those people’s bank accounts, and those who have debt may not be able to obtain the money they need to pay interest. Then there will be default unless new debt (and thus new money) is created. But again, this can only happen in the face of the kind of spending leakages that I was talking about already in my previous post.

But note that those spending leakages can also happen without interest payments. So clearly it is not interest that is problematic; it is spending leakages that ultimately cause problems.

So you can argue that under the current system, the government is not doing enough to prevent these kinds of spending leakages, either by injecting new money (government deficits) or by taxing accumulated wealth. From an academic point of view, that would be a more fruitful debate than some ultimately hopeless claims about interest.

Even in such a truly mythical world …Nicolai Hähnle

It’s not so mythical, a 100% reserve gold standard (which I oppose but not necessarily the 100% reserve requirement) approximates that since the mining rate of gold is relatively small.

But I see your point that a concern about compound or even just unspent interest is a subset of the more general problem of saving (spending leakage). How sad then that in our system saving is a necessity? But not of course if, as you say, the monetary sovereign accommodates that desire for private saving by deficit spending.

So then, instead of relying on credit to provide the ability of some to save fiat (by driving others into debt), how about we let the monetary sovereign provide the desired savings (by deficit spending) so that all may save if they desire?

And thanks for the patient explanation too.

@F.Beard: “So then, instead of relying on credit to provide the ability of some to save fiat (by driving others into debt), how about we let the monetary sovereign provide the desired savings (by deficit spending) so that all may save if they desire?”

Agreed. That’s pretty much what Bill keeps telling people every week Monday through Friday 😉

I haven’t worked through the logic of it all yet, but I think the key mistake being made in concluding that bank interest is unsustainable without a net add of dollars to the system is that, while the argument seems to assume that no one is saving his income, the argument actually assumes that banks are saving all their interest income. But if banks were to spend their entire income back into the system then it becomes available to borrowers to make future interest payments, so the system can remain in equilibrium.

It is the saving of income, by anyone in the system including banks, that necessitates the addition of net dollars by government if the economy is not to shrink.

F. Beard, the Central Bank does not destroy the money it receives as interest; it reports it (minus costs) as profit which then gets paid to the government …

… whereupon the government effectively destroys it, just as it does with tax receipts.

It is the saving of income, by anyone in the system including banks, that necessitates the addition of net dollars by government if the economy is not to shrink. Simeon

Because some people are in debt?

But common stock, used as a private money form, requires no borrowing. Instead, the common stock is spent, not lent, into existence.

So our economic problems come down to an unwillingness to “share”? 🙂

It seems to me that, even supposing the idealised situation where all interest income is respent into the economy, there is the micro consideration of how this money gets into the hands of debtors, so that they can pay their interest.

Just because something is theoretically sustainable at the macro level, doesn’t mean it is sustainable at the micro level. Somehow we have to assume that rentier income “trickles down” to debtors. The example of the debtor who works for the banker in order to earn the interest with which to pay their loan is instructive, and reflects the fact that interest ultimately is paid from the blood, sweat and tears of debtors, but it’s not very realistic at the micro level, it appears to me.