I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

US unemployment is due to a lack of jobs whatever else you think

I read an interesting study today from the Brookings Institute (published August 29, 2012) – Education, Job Openings, and Unemployment in Metropolitan America – which aims to provide US policy makers “with a better sense of the specific problems facing metropolitan labor markets”. The paper concludes that “the fall in demand for goods and services has played a stronger role in recent changes in unemployment” than so-called structural issues (skills mismatch etc). This is an important finding and runs counter to the trend that has emerged in the policy debate which suggests that governments are now powerless to resolve the persistently high unemployment. The simple fact is that governments have the capacity to dramatically reduce unemployment and provide opportunities to the least educated workers who are languishing at the back of the supply queue in a highly constrained labour market. The only thing stopping them is the ideological dislike or irrational hatred of direct public sector job creation. Meanwhile, the potential of millions of workers is wasted every day. Sheer madness!

The paper by one Jonathan Rothwell notes the disparity between metropolitan labour markets in the US – with some (19 in all) enduring unemployment rates (as at May 2012) of “less than 2 percentage points” above the “pre-recession minimum”, while “another group of 31 metro areas” continue to have an “unemployment rate … at least 4 percentage points above its pre-recession minimum”.

The paper recognises the difference “between short-term (i.e. cyclical) and long-term (i.e. structural) characteristics” where the crisis has generate cyclical unemployment (although I would dispute the inference that it is “short-term”) and this has been overlaid “a shift in developed countries towards higher skilled non-routine labor since the 1960s and 1970s.”

The paper wonders whether “the Great Recession exacerbated structural issues in the labor market” given that “the current period is the only recovery since 1948 in which jobs have not recovered their pre-recession level after three years”.

It also notes that many economists are attempting to explain the high unemployment rates of unskilled workers in terms of the workers not being qualified for the vacancies on offer.

An early and important conclusion is that:

… the evidence suggests that the need for higher education is mostly a long-term problem that is not the primary factor responsible for increasing unemployment rates since the recession began; the fall in demand for goods and services has played a stronger role in recent changes in unemployment.

In all the recessions that have occurred during this neo-liberal era (since the late 1970s) mainstream economists seek to deny that the unemployment is due to deficient aggregate demand. Rather, they attempt to argue that underlying “structural” factors such as minimum wage levels, welfare payments (so-called replacement rate variables), on-costs imposed on employers etc (so-called tax wedges) are to blame.

In every recession that I am familiar with (having studied the dynamics very closely for several years) these “structural” factors have not risen much at or near the time the unemployment has sky-rocketed. What has changed at those times is the sharp fall in aggregate demand and job vacancies (both demand-side factors).

When I have attempted to verify the importance of the factors such as tax wedges, welfare payments etc using the same data sets as several influential OECD studies I cannot find the conjectured effect once the data is carefully rendered invariant to the business cycle. We make that point in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned.

This Paper supports the view that the slump in aggregate demand is responsible for the rise in US unemployment since 2007, which is should stop the naysayers going on about structural remedies.

Further, the paper rejects the view that the unemployed are either unwilling or not skilled enough to take the jobs that are offer. It says:

The problem is a lack of job openings, rather than difficulty filling available jobs. Given that more than half of new jobs typically come from establishments started within five years, the lack of openings implies a need for more entrepreneurship, as well as higher demand.

Firms find it hard starting up when demand for goods and services is weak. New business fail at a spectacular rate in the first year at the best of times. But at present are not the best of times.

The study uses the Conference Board Help Wanted Online Data Series (HWOL) which allows it to “track jobs that are currently available.”

It also constructs the “education demand per occupation” which is a calculation based on “six education categories (less than high school, high school, some college, Associate’s degree, Bachelors degree, Masters, Doctorate/Professional degree)” across “every minor occupational category

in the United States” You can read the paper in detail if you want to technical details.

The author says that:

.. the average years of education demanded by all job openings in a metro area is the weighted average of the educational requirements of each individual job opening in that metro area.

This allows him to compute what he calls an “education gap” which is:

… calculated as the years of education required by the average job vacancy in a metropolitan area divided by the years of education attained by the average working-age person in that metropolitan area. Subtracting by one and multiplying by 100 yields the percentage gap between supply and demand. Index values greater than zero signal an insufficient supply of educated workers in the regional labor market relative to demand. Values below zero indicate that the average worker has enough formal education to do the average job. A value below zero does not mean that all workers have enough education.

The conclusions of the paper are interesting and predictable.

First, the more educated workers have lower unemployment rates and higher participation rates. That is a common finding in these types of studies.

The paper says that “One explanation as to why less educated workers struggle to find work is that there just are not enough job openings available for them” and the evidence shows that only “24 percent of all jobs in 2012 are available to workers without at least some post-secondary education”. This partly due to the fact that the “housing market crash that began in 2006 lowered demand for less educated construction workers in particular.”

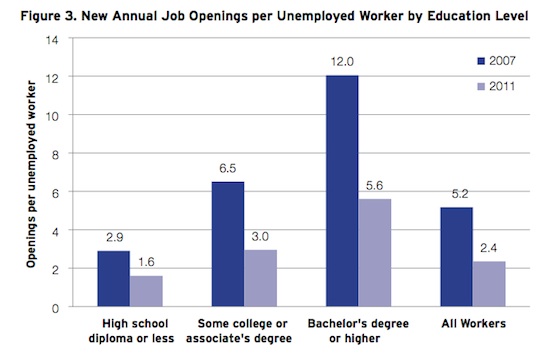

The author provided the following graph, which shows the “job opportunities for the unemployed varied by education group both before and after the recession, in 2007 and 2011.” The results are obvious. The paper points out that “(m)any of the occupations advertised most online have relatively high educational requirements.”

Underpinning the cyclical shortage of jobs is the fact that “existing jobs tend to require considerably less education than those advertised online” which means “that for every retirement, layoff, or expansion, the replacement jobs or new jobs will require more education. This presents a major challenge to many less educated workers and less educated metros”.

This leads the author to conclude that while the jobs lost in the downturn were due to “(d)eclines in industry demand and housing prices … education gaps explain most of the structural level of metropolitan unemployment over the past few years”. Which means that firms that are investing in new plant and seeing their way to offer new jobs eliminate old technologies and which deals the unskilled out of work and likely economises on labour overall (labour-saving technical change).

At the present time one cannot conclude that US unemployment is structural because while the unemployment rates for the more educated workers are lower than their lower educated brethren, the fact remains that the unemployment rates for the most skilled are still well above the pre-recession level.

Meaning? That there are not enough jobs overall.

Further, with the US labour market now locked into a situation where the tepid employment growth barely absorbs new entrants and the most disadvantaged workers are being trapped in long-term unemployment. In this state, we get what the institutional labour economists (like me) call “bumping down”.

Accordingly, when there is an overall shortage of jobs, higher-skilled (more educated) workers tend to take jobs that were previously occupied by lower skilled workers. The low-skilled are then forced out into the unemployment queue. So there are two inefficiencies: (a) the skills-based underemployment; and (b) the unemployment.

Bumping down is one of the costs (inefficiencies) of recession – the part of the iceberg that lies below the water!

The point is that some workers are able to transit into new jobs (which may be below their skills levels) while other workers suffer entrenched unemployment. You may shuffle the queue somewhat through training and depriving the unemployed of income support but when there are not enough jobs you will not reduce the unemployment rate at all. All you will do, if successful, is shuffle who endures the unemployment.

A vast body of literature from the 1950s onwards describes the manner in which the labour market adjusts to the business cycle.

The literature also ties in with some versions of segmented labour market theory. Together they provide the basis of a theory of cyclical upgrading, whereby disadvantaged groups in the economy achieve upward mobility as a result of higher economic activity.

Arthur Okun’s 1973 work – Upward Mobility in a High-Pressure Economy – (published Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, pp. 207-252) noted that when there is a cyclical downturn commentators focus on the movements in unemployment but ignore the other costly manifestations of the cycle. He said that unemployment was only the tip of the iceberg.

He coined an expression – on a high tide all boats rise – meaning that all the forms of cyclical wastage are reduced and the weak and the small also benefit when the cycle turns up.

He summarised the submerged parts of the cyclical iceberg as follows:

- The most cyclically sensitive industries had large employment gaps, were dominated by prime-age males, offered high-paying jobs, offered other remuneration characteristics (fringes) which encouraged long-term attachments between employers and employees, and displayed above-average output per person hour.

- In demographic terms, when the employment gap is closed in aggregate, prime-age males exit low-paying industries and take jobs in other higher paying sectors and their jobs are taken mainly by young people.

- In the advantaged industries, adult males gain large numbers of jobs but less than would occur if the demographic composition of industry employment remained unchanged following the gap closure. As a consequence, other demographic groups enter these ‘good’ jobs.

- The demographic composition of industry employment is cyclically sensitive. The shift effects are in total estimated (in 1970) to be of the same magnitude as the scale effects (the proportional increases in employment across demographic groups assuming constant shares). This indicates that a large number of labour market changes (the shifts) are generally of the ladder climbing type within demographic groups from low-pay to higher-pay industries.

So when the economy is maintained at full employment, workers in low paying sectors (or occupations) also receive income boosts because employers seeking to meet their strong labour demand offer employment and training opportunities to the most disadvantaged in the population. If the economy falters, these groups are the most severely hit in terms of lost income opportunities.

Upgrading also focuses on the mapping of different demographic groups into good and bad jobs. The groups who experience the greatest relative employment gains when economic activity is high are those who are stuck in the secondary labour market, typically, teenagers and women.

While these groups are proportionately favoured by the employment growth, the industries with the largest relative employment growth are typically high-wage and high-productivity and employ mostly prime-age males.

Expansion is therefore equated with ladder climbing whereby males in low-pay jobs (as a result of downgrading in the recession) climb into better jobs and make space for disadvantaged workers to resume employment in their usual sectors. In addition, favourable share effects in predominantly male industries provide better jobs for teenagers and women.

So fiscal austerity approaches that deliberately maintain low pressure in the economy and stop the tide from rising impose substantial costs that go well beyond those that we can easily see in terms of official unemployment.

The paper we are discussing today also examines the claim “by “that high unemployment rates during this recovery have been prolonged by a skill mismatch”. The argument goes like this:

If the skills (or education) of unemployed workers does not match what employers need, vacant jobs will remain unfilled even as the economy expands, or employers will invest in technology (e.g. computers or machines) to do the work or offshore it. The unemployment rate will remain high. For this theory to hold, one would expect that the education gap would explain short-term changes in unemployment as well or better than industry demand and housing prices. As discussed above, this is not the case. Growth in industry demand and housing prices has brought down unemployment.

Additionally, one would expect that jobs have become more difficult to fill during the course of the recession, compared to before the recession, and that metropolitan areas that take longer to fill jobs would have higher unemployment rates. Both of these latter predictions are also not supported by the evidence.

In fact, the metropolitan labour markets with the highest unemployment “easily fill jobs” and the “education gap is not correlated with the share of openings that go unfilled.”

So put that myth to bed!

The latter part of the paper considers the way jobs are created in the private sector and finds that “(m)etro areas with a lower education gap appear more entrepreneurial, as evidenced by their higher rate of job openings.”

What does this all mean?

The author concludes that the results “emphasize the increasing importance of education for vacant jobs”, which is no surprise in a demand-constrained labour market and a labour market that is, in trend terms, shedding unskilled jobs (and shipping them to poorer, lower-wage nations).

Taking that into consideration, the author cautions that:

In the short term, any mismatch between the supply of and demand for education is not a sufficient argument against further stimulus and expansionary policies.

The author also concludes that the decline in unskilled work pre-dated the recession – which “did not fundamentally change the structure of the economy in terms of the supply and demand for skills or education.” So education:

… is hugely important to metropolitan labor markets in the long-run because it fuels innovation and because technological-change has complemented highly educated workers, while displacing many less educated workers. Short-term changes in unemployment are largely driven by industry demand and housing markets …

My conclusion from studying the raw data (which you can download from the paper’s home page) and analysing the results of the paper is not at odds with the author’s conclusions.

The reality is that there are not jobs overall and that is exacerbating the longer-term trend away from private unskilled job creation. There has been a global shift in demand for unskilled work away from the richer nations towards the low-wage nations such as China and India. The brain-work is still mostly done in the richer nations although that also is being undermined by the massive public investment in education in nations such as China.

Governments are ultimately responsible for seeing that all citizens are able to contribute to society up to their potential. The private market is incapable of fulfilling that role as is clearly evident.

So if you believe in eliminating waste – which is a primary concern of “economists” (by definition) – then ensuring everyone contributes to their potential must become the responsibility of our governments.

It amazes me how poorly thought out the arguments in the public debate are which oppose this role of government. I know that the proponents have a religious attachment to the utopian idea that private labour markets will work if only they are allowed to. So the usual suspects are invoked – cutting minimum wages, eliminating or severely cutting and curtailing welfare payments, eliminating regulations pertaining to occupational health and safety etc.

The evidence doesn’t support any of those policy changes in relation to economies that have insufficient work and a bias in new work away from the poorly educated.

In fact, cutting minimum wages and income support payments is likely to make the spending shortfall and hence employment worse.

The reality is that rich nations will have to address both the shortage of jobs overall and the bias towards skill.

Rising inequality is unsustainable so a means has to be found to ensure the less skilled workers participate in the productivity growth of the nation through higher real wages.

At the very least, governments should introduce a Job Guarantee to ensure that all workers, irrespective of their educational attainments, can enjoy access to work when the private sector and mainstream public sector is not providing enough work.

A nation that desires to allow workers to achieve their potential has to use public employment buffer stocks.

In studies such as the paper I considered today, there is an implicit (at least) bias towards a specific concept of a job. Private markets are not the sole arbiters of what constitutes productive and meaningful work.

While the dynamics of the private market are steadily undermining the job opportunities of the lowly educated even apart from the cyclical downturn at present, that doesn’t mean that the solution is to educate everyone to higher levels.

I personally place a high value on education but I also realise – from experience and research – that there is a distribution of propensities in every population – which means that some workers will not achieve satisfactory results through formal education programs (such as university study).

For many workers – especially those who are seeing their usual jobs disappear off-shore – there are other ways that a society can productively deploy their talents.

The public sector could easily provide “good jobs” for “high school drop-outs” with structured skill development opportunities. There are millions of productive jobs that could be designed, for example, to advance personal care service and environmental care service in the US (and elsewhere).

Jobs come and go. Think about the decline of agriculture, the rise and subsequent decline of manufacturing, and the rise of service employment. These transitions are on-going. It doesn’t mean that you have to have unemployment.

In December 2008, we released a major report – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy – that was the result of a 3-year national study.

The research that underpinned the Report conducted a national survey of local governments in Australia. We identified hundreds of thousands of jobs that would be suitable for low-skill workers in areas such as community development and environmental care services. There is enormous unmet need for public works across regional Australia. For larger economies, the estimates would run into millions of jobs.

Further, we outlined an effective role for the state in direct skill formation through a National Skills Development (NSD) framework which we consider could be integrated into the Job Guarantee.

Full employment can be maintained by the introduction of an open-ended (infinitely elastic) public employment program that offers a job to anyone who is ready, willing and able to work and cannot find alternative employment.

These jobs ‘hire of the bottom’ in the sense that the minimum wages paid which are not in competition with the market sector wage structure. By avoiding competing with the private market, the Job Guarantee anchors the nominal value of money and the economy avoids the inflationary tendencies of old-fashioned ‘military Keynesianism’, which attempts to maintain full capacity utilisation by ‘hiring off the top’ (making purchases at market prices and competing for resources with all other demand elements).

The sort of jobs that could be generated by the public sector will never be offered by a private-profit seeking private sector. So the idea that there is some sort of long-term structural mismatch between the jobs on offer and the skills available presupposes that there is nothing that the public sector can do to provide inclusion to the poorly educated workers.

That presumption is categorically false and reflects an ideological dislike of public sector job creation.

Conclusion

The Brookings Paper was an interesting reminder of the knowledge that sound research rather than knee-jerk ideological posturing provides.

Yes, the long-term issue for rich nations is finding work for the poorly educated in an environment where that work is increasingly disappearing and being shipped abroad to lower wage nations.

That long-term challenge has to be met by an increased public sector direct job creation because the type of work that will be inclusive for all will not be provided en masse by the private sector.

In the short-term, the overall problem however remains a lack of aggregate demand placing orders with firms. The solution is as the paper concludes to use expansionary monetary and fiscal policy to increase the growth in overall spending.

Then a Job Guarantee which would help ease the pain of both the trend and the cycle would find some long-term level and social inclusion would be the norm. We would all be better off by far.

This week

It is a big data week in Australia. Tomorrow the RBA meets to determine interest rates. Wednesday the second-quarter national accounts come out and Thursday, the August labour force survey data comes out. Today, retail trade and company profits data came out with some bleak trends emerging.

For the media who normally contact me for commentary about each of these data releases, I will be fine tomorrow but for Wednesday’s National Accounts I will not be available for interviews until the next morning (EAST). I will also not be able to write a blog about the data release until early Thursday morning (EAST) and it will be coming from Brussels. My phone contact is as always.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

The educational level that employers demand depends on the context. If in a certain country 80% of adults have a highschool diploma and unemployment is high, then all kinds of employers may demand a highschool diploma. If only 60% of adults have a highschool diploma and the labor market is tight, then the same employers may no longer demand that applicants have a highschool diploma.

The labor market is like the rental market. The higher the vacancy rate the less choosy landlords can be. If the vacancy rate is very low, landlords may refuse to take students, which they’ll start accepting when the vacancy rate rises. Similarly, the tighter the labor market the less choosy employers can be. All employers prefer people who don’t need any training. If they can’t find such people, they’ll settle for people who need a little training. If those aren’t available either, they’ll accept those who need more training. The best friend of the wage-earning class is a tight labor market.

Another factor to consider is that skilled people can do unskilled work while unskilled people can’t do skilled work. An accountant can end up working as a waiter but a waiter can’t work as an accountant. If skilled people can’t find work for their skill, they may invade the territory of the unskilled, thereby increasing competition in that market and making it still harder for the unskilled to find jobs.

Regards. James

All this emphasis on jobs! Have people forgotten that being forced to labor is a curse? A curse that has largely been overcome due to automation?

However, the benefits of automation have not been justly shared because of the way automation was financed – with the stolen purchasing power of the workers via loans from a government backed counterfeiting cartel, the banking system.

Just hand out money to the population (Steve Keen’s “A Modern Debt Jubilee”) and you bypass arguments about the size of government AND you provide just restitution to a looted population.

” but a waiter can’t work as an accountant”

That may of course be more to do with the accountant’s trade union (aka ‘professional organisation’) ability to lobby to raise barriers to entry than any intrinsic lack of ability on the waiter’s part.

In a world of computerisation you don’t really need vast training to be an accountant.

By the way, higher ed has also been financialized. A student is now expected to finish their undergraduate education with ~ $130,000 in debt. Which they will be paying to the rent-seeking financial sector for a good portion of their lives. See, Charles Ferguson, ‘Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America’.

“Have people forgotten that being forced to labor is a curse?”

Not as much as some people forget that labouring is of huge social benefit and many people like being and even need to be told what to do (hence the continued popularity of the military).

For many automation is a curse. Something the Luddites drew attention to precisely 200 years ago.

Not as much as some people forget that labouring is of huge social benefit Neil Wilson

If the work is useful, yes. It can also be terribly demoralizing if it is not. But if you want the population gainfully employed in a social sense, a return to family farms (stolen by the banks) would be very useful.

and many people like being and even need to be told what to do (hence the continued popularity of the military). Neil Wilson

People can always volunteer if they like being told what to do. Of course then they can not justify their evil actions by the necessity of earning a living.

For many automation is a curse. Neil Wilson

Only because it denies them an income – no one is forced to use automation in their private lives. I knew a girl who used her dishwasher as storage space because she liked to wash dishes by hand.

Sometimes I think you guys are more interested in harnessing the power of MMT to promote your own social agenda than to end this depression. Let’s aim for justice instead. Who can oppose that?

Good post.

Reading this I was stuck by the similarities with a book I’m reading: Poor Economics by Banerjee and Duflo.

The “poor” in this case are those stuck in poverty, not negligent economists (although the book does acknowledge the poverty of contribution from the ‘discipline’ of economics – not strongly enough for my taste!)

They work in some of the poorest countries and focus on sound empirical research, attempting to be free of political ideology or spin from those delivering their brand of “cure”. They often present a leftie/Sachs view vs a conservative/Easterly view to development and use their empiricial results to analyse which parts of each argument holds up to scrutiny and which are likely to be based on preference/assumptions/ideology.

Their findings towards the end of the book are excellent. Despite their focus being on developing nations, their findings are surely applicable everywhere, being grounded in real human behaviour which at a base level is fairly cross-cultural. I think you would find it useful Bill. They eventually come to the conclusion (slightly hesitantly given that they’re in a mainstream framework) that for all the entrepreneurial microcredit programmes or foreign aid handouts, the most effective way out of poverty is to simply give people the security of a stable job, and the simplest way for that to happen is for the Government to create those jobs.

They’re not macroeconomists but there’s little doubt in what they are saying their data shows – and it’s the very same conclusion that MMT suggests: Government Job Guarantee. The difference is, MMT shows you how the government can pay for it.

“People can always volunteer if they like being told what to do.”

Volunteer to whom?

To whomever. There are scads of volunteer organizations like the Red Cross, Meals on Wheels, Habitat for Humanity, Salvation Army, etc.

“To whomever. There are scads of volunteer organizations like the Red Cross, Meals on Wheels, Habitat for Humanity, Salvation Army, etc.”

All of whom have enough volunteers at the moment and can’t cope with any more – because they don’t have sufficient paid organising staff. It’s one of the issues with using volunteer organisations to administer a JG. Even with heavy decentralisation you still need the ability to direct and somebody to do the direction.

These things do not arise spontaneously any more than full employment arises spontaneously – as anybody who’s spent time on an Open Source IT project knows only too well.

One of the beauties of MMT is that it annoys the left and the right in equal measure – puncturing both their idealisms with a heavy dose of pragmatic common sense. And that’s the reason why it’s likely to be close to a workable solution.

MMT does not annoy me; it’s your refusal to recognize that the population has been cheated by a counterfeiting cartel and deserves RESTITUTION, not make-work.

US banks have $8.6 Trillion in liabilities unbacked by reserves. That means that $34,400 could be GIVEN to every US adult, including non-debtors, without increasing the total money supply IF the restitution was combined with a 100% reserve requirement for new loans and IF the restitution was metered to just replace existing credit debt as it is paid off.

Banking reform plus restitution is the proper way to go. It would benefit nearly everyone.

“MMT does not annoy me; it’s your refusal to recognize that the population has been cheated by a counterfeiting cartel and deserves RESTITUTION, not make-work.”

The knee-jerk right reaction that any government work is, by definition, make work. Was the Interstate Highway System make-work? Rural electrification? The creation of the Internet?

So instead of having the government engage the unemployed in useful work you’d rather give everyone a cash grant? That could alleviate the debt overhang, but it does nothing to repair our crumbled infrastructure.