The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The Eurozone is both a spectacular failure and a spectacular success

One of the ways I judge whether an economy is working is whether it is able to provide enough work for those who desire it (both in number of jobs and hours of work). That is, an economy that generates purely frictional unemployment with underemployment eliminated. I know that there are many that think that emphasis is old-fashioned but those opinions are mostly provided by those that have secure, well-paid jobs. The latest Eurostat European Labour Force data, May 2012 shows that the policy framework in Europe is failing dramatically against my benchmark with the unemployment rate is now at its highest level in the Eurozone since the currency union began. I judge the Eurozone to be a failed “state”, in need of a dramatic change in policy approach. At the same time I consider it to be spectacularly successful. Time to explain …

Yesterday, I quoted Chicago economist Robert Lucas, Jnr who said that “At research seminars, people don’t take Keynesian theorising seriously any more; the audience starts to whisper and giggle at one another.”

Those who pronounce that unemployment is voluntary (a “preference for leisure”) or that youth unemployment is just a search process and the higher rates of unemployment just reflect that they are searching more intensively because they have less knowledge, and the rest of the sickenly false reasons that the mainstream elicit to defend their indefensible position are typically well-paid persons in secure employment with large superannuation balances and consulting income on top of their university income.

I have been researching unemployment for my entire career and I have yet to meet an unemployed person who prefers leisure any more than I do or most people. They are just the people who bear the brunt of deficient aggregate (effective) demand, which arises from poor policy choices from our governments.

There was a lovely retort from veteran Cambridge economist Frank Hahn’s 1982 book Money and Inflation (published by Blackwell), which is relevant to today’s blog and that observation. The book was a collection of lectures that Frank Hahn delivered at Birmingham University in 1981. to that

I don’t have the book near where I am working today but Tony Thirlwall quoted Hahn in a paper that he presented to a meeting at Cambridge a few years ago (that both Randy Wray and yours truly also gave papers). Frank Hahn was discussing the Lucasion (that is, Monetarist) denial of the concept of involuntary unemployment and Thirlwall quoted him as saying:

I wish he … [Robert Lucas] … would become involuntarily unemployed and then he would know what the concept is all about.

As an aside, Frank Hahn was not one Keynes’ inside coterie. He was critical of Keynes for his lack of technical skills and exposition.

In the Preface (Pages x-xi) to his 1982 book – Money and Inflation – Hahn wrote that while he was extremely critical of the Monetarist theoretical position, he also didn’t think much of Keynes. He wrote:

It is of course true that the Keynesian orthodoxy was also flimsily based and that its practitioners also dealt in unwarranted certainties. I do not wish to defend this. But bygones are bygones, and these economists are not now stridently to the forefront. However, I ought to lay my cards on the table. I consider that Keynes had no real grasp of formal economic theorizing (and also disliked it), and he consequently left many gaping holes in his theory. I nonetheless hold that his insights were several orders more profound and realistic than those of his recent critics.

When Hyman Minsky reviewed Hahn’s book in 1984 (Reference ‘Hahn’s “Money and Inflation”: A Review Article’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 6(3), 449-457) he said that:

Hahn’s attack on Monetarist expectations is consistent with the Post Keynesian critique. But Han is not a closet Post Keynesian. He “believes” that Arrow-Debreu can be used as a basis, a “scaffolding”, for useful theory. Post Keynesians accept the logic of arguments such as those in Hahn’s critique and work at developing a monetary theory that fully recognizes the complex institutional structure of modern capitalism. It is sad but Hahn, for all his talent and power, doesn’t even try to understand our economy.

Anyway, lets progress.

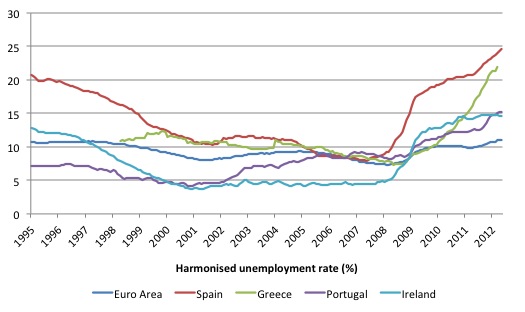

The latest European Labour Force data, May 2012 – published this week (July 2, 2012) by Eurostat show that the Euro area unemployment rate is now at 11.1 per cent, the highest level since the Eurozone was formed.

The first graph shows the aggregate unemployment rate at the Eurozone level and for selected peripheral Eurozone nations. The jobless rate is spiralling upwards and all the summits and bailout plans have not changed that pattern – and can be judged to have failed.

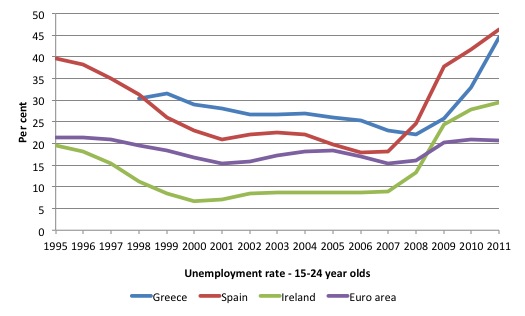

There is a host of Eurostat data conveniently arranged at the Youth Dashboard and the following graph is taken from data available there.

It shows the unemployment rate for Eurozone youth (15-24 years of age) from 1995 to 2011. The situation has of-course deteriorated further into 2012.

The latest data shows that youth unemployment in the Eurozone is 22.6 per cent, for Spain and Greece 52.1 per cent; Portugal 36.4 per cent; for Italy 28.5 per cent, and for Ireland 28.5 per cent.

I tweeted yesterday when I saw the data release that this is a lost generation being created in Europe.

The long-term damage that arises from excluding the youth from the labour market is life-long and then some. Just as this cohort will carry the disadvantage throughout their lives and typically endure unstable and low-paid work interspersed with lengthy periods of unemployment when the business cycle turns down.

But even more damaging is that they will find it harder to form stable relationships and if they do their children will inherit this disadvantage arising from the exclusion at this time of their parent(s).

It is unfathomable why this is not an absolute policy priority and the Euro leaders announce immediate job creation programs through the Eurozone targetted at youth, if they cannot bring themselves to introduce an unconditional job guarantee for all workers.

The costs of this folly are so large and so enduring that there is no fiscal justification that can be mounted to not introduce such a plan.

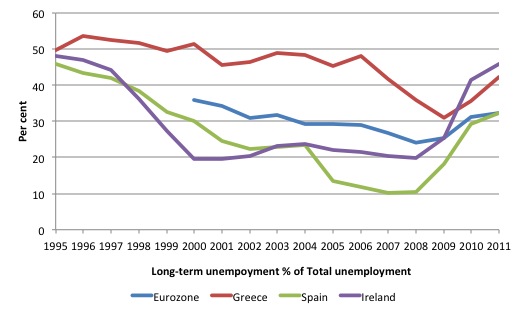

The next graph from the same database shows the ratio of Long-term unemployment (12 months or more) to Total unemployment for the Euro area and selected nations from 1995 to 2011.

This is a familiar pattern during drawn-out recessions. The pool of long-term unemployed expands as new entrants come intot th elabour markte and are seen as being more attractive relative to those who have been unemployed for some time.

This pattern also provides another argument by the neo-liberals to justify austerity. They claim that rising long-term unemployment is structural in nature and needs to be addressed via training rather than aggregate demand expansion. I have done a lot of work in this area in my earlier research.

Economists employ classification frameworks to help us make sense of the labour force data. For example, in terms of types of unemployment (with implicit causes attached), there is a distinction made between demand-deficient and structural unemployment.

Demand-deficient unemployment occurs when the number of people wanting gainful employment exceeds the number of vacancies being offered. The composition of the unemployed relative to the skills demanded is not the binding constraint.

Structural unemployment is said to arise when there are imbalances in the supply of, and demand for, labour in a disaggregated context. A simple case arises which highlights the difference as to which constraint is promoting the unemployment. If at the aggregate level the number of unemployed is equal to the number of vacancies then (abstracting from seasonal and frictional influences) this unemployment would be termed structural.

Structuralists suggest that structural imbalances can originate from both the demand and supply sides of the economy. Technological changes, changes in the pattern of consumption, compositional movements in the labour force and welfare programme distortions are among the pot-pourri of influences listed as promoting the structural shifts.

The distinction between demand deficient and structural unemployment is usually considered important at the policy level. Macro policy will alleviate demand deficient unemployment, while micro policies are needed to redress the demand and supply mismatching characteristic of structural unemployment. In the latter case, macro expansion may be futile and inflationary.

The Monetarist notions of the NAIRU are tied in closely with the concept of structural unemployment and has been used to justify the ridicule that Robert Lucas refers to in the opening quote.

By the mid-1970s, Keynesian remedies proposed to reduce unemployment – that is, demand expansion – were met with derision from the bulk of the profession who had embraced the natural rate (NAIRU) approach and its policy implications even though there was very little evidence presented to substantiate these effects in any economy in the world.

The NAIRU approach reinstated the early classical idea of a rigid natural level of output and employment. Essentially, it asserted that in the long-run there was no trade-off between inflation and unemployment, because the economy would always tend back to a given natural rate of unemployment, no matter what had happened to the economy over the course of time.

The natural rate (or NAIRU) reflected structural characteristics (you guessed it – minimum wages, welfare payments, etc) and so only microeconomic changes – that is, deregulation, welfare retrenchment, abandonment of minimum wages – could lower it. Accordingly, the policy debate became increasingly concentrated on deregulation, privatisation, and reductions in the provisions of the Welfare State – one of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal era.

But if structural changes are, in fact, cyclical in nature a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

This was, in part, one of the investigations I undertook as part of my PhD studies. As a graduate student I considered that the NAIRU concept was merely a standard (logical) prediction from the orthodox competitive model, which lacked empirical substance. There were also internal inconsistencies in the theory.

It was not difficult to find empirical evidence which was contrary to the edicts of the NAIRU approach – for example, the quits are pro-cyclical not counter-cyclical. Please read my blog – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments – for more discussion on this point.

In the real world, booms in activity stimulates on-the-job training opportunities and raises potential output above the level that would have persisted had the economy remained at low levels of activity. Alternatively, as activity falls due to demand failure, both training opportunities decline and actual skills are lost, as workers lie idle. The potential capacity level falls as a result.

To learn more about that research please read my blog – The structural mismatch propaganda is spreading … again!.

The point is that the NAIRU concept does not stack up theoretically or empirically. It is well established that changing labour market imbalances reflect cyclical adjustment processes which render any estimated macroequilibrium unemployment rate to be cyclically sensitive and therefore not the basis of an inflation constraint.

The NAIRU hypothesis suggests that any aggregate policy attempt to permanently reduce the unemployment rate below the current natural rate inevitably is futile and leads to ever-accelerating inflation.

However, the empirical world supports the notion that imbalances reverse when aggregate demand regains strength. The last thing we should be doing at present is to abandon job creation policies and start relying, exclusively, on training programs and worker-attitude-correction strategies to reduce long-term unemployment in Europe or anywhere.

I have provided this quote from Michael Piore (1979: 10) previously, but it is worth repeating:

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original) [Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., White Plains]

So why would anyone think that the Eurozone has been a success?

I read an interesting article by American investigative journalist Greg Palast recently (June 26, 2012) – Robert Mundell, evil genius of the euro – where he argued that the Euro had succeeded in spectacular fashion.

His argument was that:

The idea that the euro has “failed” is dangerously naive. The euro is doing exactly what its progenitor – and the wealthy 1%-ers who adopted it – predicted and planned for it to do.

That progenitor is former University of Chicago economist Robert Mundell … [who] … intended to do something about it: come up with a weapon that would blow away government rules and labor regulations …

The euro would really do its work when crises hit, Mundell explained. Removing a government’s control over currency would prevent nasty little elected officials from using Keynesian monetary and fiscal juice to pull a nation out of recession.

I agreed with everything he wrote and have commented before that fiscal austerity really has nothing to do with a belief that financial markets are dominant and that if the ECB funded all the stimulus necessary to regenerate economic growth there would be hyperinflation. It is clear that the Euro leaders, infested with neo-liberal zeal, want to finish off the agenda that was rudely interrupted by the crisis that that agenda actually caused.

They want to tilt the balance towards capital, undermine real wages growth and welfare benefits and return economies to states that existed before trade unions, inconveniently provided a modicum of industrial justice to the workers.

So why do I also say the Eurozone has failed? Well it is because I prefer to evaluate it from the perspective of decency rather than the ambitions of the neo-liberal elites. As noted in the opening – if a society cannot provide enough work for those who desire it then it is clearly also not lifting the fortunes of the poorest members in that society. That is my definition of a failed state.

What can be done about it? I have been invited to speak at the upcoming European Commission Employment Policy Conference (“Jobs for Europe”) in Brussels on September 6-7, 2012. At that meeting I hope to articulate a comprehensive strategy which will link in to the work already being done by the EC – see Commission presents new measures and identifies key opportunities for EU job-rich recovery – but challenge the notion that direct job creation is to be avoided.

I will obviously report more on that work nearer to the day.

But there was an article in the UK Guardian (July 3, 2012) by US economist Dean Baker – Why Americans should work less – the way Germans do – which proposed a solution to US unemployment.

Dean Baker says:

There is a solution to unemployment: if we worked the same shorter hours as Germany, we’d eliminate joblessness overnight

I don’t consider the proposal presented to be a viable solution. Rather, I characterise these proposals, however well intentioned, to be conceding ground to the neo-liberals and trying to work around the artificial constraints that the latter place on economic (and hence employment) growth.

Dean Baker notes that “on average German workers put in 20% fewer hours a year than Americans – and German unemployment has fallen during the post-2007 downturn”.

He continues:

The most important point to realize is that the problem facing wealthy countries at the moment is not that we are poor, as the stern proponents of austerity insist. The problem is that we are wealthy. We have tens of millions of people unemployed precisely because we can meet current demand without needing their labor.

This was the incredible absurdity of the misery that we and other countries endured during the Great Depression, and which Keynes sought to explain in The General Theory. The world did not suddenly turn poor in 1929, following the collapse of the stock market. Our workers had the ability to produce just as many goods and services the day after the collapse as the day before; the problem was that after the crash, there was a lack of demand for these goods and services.

I totally agree with that proposition. It reminded me of the way Norwegian economist described the situation during the Great Depression.

Jans Andvig quoted Frisch in his 1992 book – Ragnar Frisch and the Great Depression – A Study in the Inter-war History of Macroeconomics Theory and Policy (published by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, Oslo. page 287):

One has to understand that the ongoing crisis is not a crisis of real poverty, but an organizational crisis. The world is like a ship loaded by the goods of life, where the crew starves because it cannot find out how the goods should be distributed. Since the depression is not a real poverty crisis, but one of organization, the remedy should also be sought through effective organizational work inside the apparatus of production and distribution. The great defect of the private capitalist system of production as it is today is its lack of planning, that is, planning at the social level. This cardinal point cannot be disputed.

Frisch was concerned about income distribution as much as the level of aggregate demand. He was also an antagonist to Keynes, because the latter eschewed the value of econometric modelling as a tool to aid interventionist policy. I will write about Frisch in detail another day because he is a very interesting character with some very original policy ideas.

The question that arises then, is what policies are required to ensure these “organisational problems” are resolved.

Dean Baker acknowledges that the “result of this lack of demand was a decade of double-digit unemployment in the United States” during the 1930s and that the “spending programs of the New Deal helped to alleviate the impact of the downturn”.

He also says that this “is the same story we face today”. I agree totally.

But he then claims that governments:

… can also employ people by encouraging employers to divide work among more workers. There is nothing natural about the length of the average work week or work year and there are, in fact, large variations across countries. The average worker in Germany and the Netherlands puts in 20% fewer hours in a year than the average worker in the United States. This means that if the US adopted Germany’s work patterns tomorrow, it would immediately eliminate unemployment.

He wants the “lost wages will be made up by subsidies from the government” because he understands that “the problem is too little demand, not too much”.

Let me say that I support shorter working weeks to give workers more time to spend with the families, friends and otherwise. Productivity growth should allow real wages to rise and the working week to fall.

But relying on shorter working hours to solve the unemployment problem will not eliminate that evil.

It is clear that aggregate demand has to grow for output and employment growth to occur, unless governments introduce a Job Guarantee scheme and simultaneously engineer a transfer of workers into that pool from existing employment.

That is, a JG scheme does not necessarily require aggregate demand to grow. A government would be perverse if it adopted fiscal austerity and suppressed demand while at the same time introduced a JG.

So the solution at present has to include an increase in the budget deficits in nations that are enduring high unemployment. That is recognised by Dean Baker, when he notes that the German response to the crisis was to ration hours of work and the state would pick up the tab to ensure incomes of workers on shortened hours would not fall by much.

I considered the German approach in some detail in this blog – Shorter hours or layoffs? – and concluded that the German case provides a better option relative to laying off workers. But the comparison between Germany and the US is fraught given the radically different welfare support levels in place in each nation. US has no safety net at all.

There are several arguments advanced in favour of using shorter hours. First, it allegedly allows the burden of recession to be shared instead of a small relative percentage of workers bearing the costs in the form of unemployment. However, given that recession does not impact evenly on sales and across firms (that is, some industries and therefore firms are more vulnerable) this “sharing” is not possible. Some firms cannot survive even with shorter hours while others do not need to cut hours at all.

Second, unemployment requires some workers to lose all their pay whereas sharing hours would proportionately reduce pay for all workers. While there is some merit to this argument, it doesn’t help those workers who are on the margin of solvency with respect to their nominal contractual commitments (for example, mortgage payments). Further, given that wage income is a significant component of final demand – a widespread cut in pay (via less hours) would see aggregate demand fall and unemployment worsen. Some proponents of short working weeks argue that the pay issue can be overcome if the government pays workers a portion (might be 100 per cent) of the difference they earn from the firm and what they would have earned by working a full week. This is of-course the solution that is followed, to some extent, in countries such as Germany (see below). However, it is problematic if there is significant casualisation in the workforce. What is the standard working week that the subsidy would be based on? This would be particularly difficult in Australia, where like the fools we are, we have allowed underemployment to skyrocket.

Other suggestions to the pay dilemma include the provision of tax credits to firms to cover paid time off. So a government subsidy in another guise. Whether this is the best use of government spending is moot given the opportunity that it provides private firms to abuse the system.

Third, some argue that sharing hours is good because it frees up more time for leisure and families. It does that by definition but while that might benefit some it may also disadvantage others, especially lower paid workers. Leisure and income tend to be complementary in this consumer age and a loss of pay may reduce the capacity to enjoy leisure.

Fourth, less congestion on roads makes for higher standards of living. Sure enough. Flexible hours would spread the traffic usage across a broader spectrum of available hours. But why not just petition for better public transport and improved bicycle paths? We don’t need schemes that cut workers pay to improve transport systems. What we need is a commitment by the Government to build high quality public infrastructure. If they saw the recession as an opportunity to accelerate the construction of public spaces (including bike paths and better transport) then a lot of the need to cut hours would disappear as the net government spending underwrote aggregate demand and jobs.

The same logic underlying Dean Baker’s proposal was used by the French when they brought in a statutory 35-hour working week in February 2000. It was seen as a way of “spreading the work” and reducing their persistently high unemployment rates.

The facts that emerged were that employers did not hire new workers in any great quantity and unemployment remained largely unchanged (as a consequence of this move). The evidence is that the workers who kept their jobs enjoyed longer weekends which created a real estate and sports-centre cum golf boom in the 100km radius of Paris (for example). But the bosses just increased intensity of work and so 5 days work was performed in 4 days.

The problem is that while it has improved the lives of many of those in employment it did virtually nothing for the unemployed.

So the plan to spread the work failed. I imagine Dean Baker will say that to get the subsidy the firm has to shuffle the hours. But what incentive is there for the firms to do that if it not going to sell more goods and services and may add to their labour costs?

There are also many within-firm issues which add costs. In all but the lowest skill jobs, the act of hiring is costly. Further, workers are not perfect substitutes and so work-sharing can be difficult to organise. The inflexibility it introduces when a matching worker is not available increase employer costs. The administrative burden of adding to the payroll etc add costs. There are also spatial (regional) matching issues. So where is the incentive for the employer?

Workers have other commitments/obligations which are not necessarily as flexible – such as child care arrangements. If the boss can tell the worker to take a holiday (employer chooses remember) this might not align with these other responsibilities. While flexibility for the worker in terms of hours might seem like a good idea, in many cases it becomes a poisoned chalice.

Further, who determines where the flexibility will occur? Dean Baker’s Centre (CEPR) has proposed this before and placed the so-called flexibility in the proposal at the behest of the employer! SHE gets to decide how the worker will be rationed off into idleness.

Finally, given that the US government (or the ECB in the Eurozone) issues the currency it can easily ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient in the economy by stimulating employment rather than rationing it.

For Dean Baker’s proposal to get past the demand constraint government net spending has to rise anyway. That means it has to get past the current ideological constraint that is stopping that from happening.

Once that constraint is eliminated then rationing hours is not going to be the best way to solve unemployment.

Conclusion

I would rather see that stimulus initially be introduced via an employment guarantee with increased minimum wages (in the US). The limit of the guarantee and the last dollar that would have to be spent would be determined by the last unemployed worker who came through the Job Guarantee door wanting to work. A down-to-the-last-dollar automatic stabiliser you might say which eliminates all the complaints made by the mainstream about fiscal policy inefficiencies arising from timing lags.

The US government and any national government can always afford to introduce this sort of program. Shuffling workers around a highly constrained volume of working hours is not a progressive solution. It is a compliant surrender to the failure of the US government to realise its fiscal responsibilities.

Once that was in place, I would then undertake major public infrastructure projects to employ skilled labour and ensure public health and education was well funded (which means in the US context I would be funding states via federal transfers proportionate to population).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

why not employ and train highly qualified staff to undertake major infrastructure projects

which would have massive positive effects for the private sector invest in health and education

and then see if any low paid job guarantee work was needed and where this might be directed?

Kevin Harding- that’s what all our beloved MMT gurus recommend. But in any monetary economy, there’s always going to be a residual level of unemployment. Either that, or our lofty spending aims will just be inflationary. Inflation will do the balancing of goals, and screw the creditors, succor the debtors.

The JG just means the government does not make the insane demand of the involuntarily unemployed that they pay it for the necessities of life, without providing them the means of doing so. That old-fashioned Old-Keynesian spending will succeed in non-inflationarily eradicating unemployment permanently is believing that it is very easy to balance an economy on the head of a pin.

The JG puts the responsibility where it lies – on the government, and ends human sacrifices to expiate inevitable bureaucratic “mistakes” in achieving an impossible goal.

“The JG just means the government does not make the insane demand of the involuntarily unemployed that they pay it for the necessities of life”

Slightly more than that AIUI.

The JG maintains people as work-ready. They can be seen to be work ready, and have it validated by a third party, rather than just saying that they are. That reduces hiring risk and therefore reduces costs.

That reduced cost flattens the inflation curve as you move towards real full employment, so for a given inflation rate you can have a higher number of people employed.

An unemployed buffer will generate demand pull inflation long before an employed buffer does.

That’s why MMT economists are so big on the JG. It has a specific additional effect on employment and inflation.

it seems that there is so much that needs to be done with skilled labour which is vital to the development of the economy eg how long before the lights go out in europe if we don’t develop new energy sources that such work should take priority .

it also seems that infrastructure investment normally accompanies higher growth rates which would drive down govt defects through the automatic stabilizers

it’s hard to model potential inflation in the face of substantial improvements of both quantity and quality in goods and services

if inflation became the new priority adjustments could be made

to get to the place you wanna go you might have to find it on the map first

will investment in mass transportation systems and roadbuilding deflate transport costs?

will investment in house building rent and mortgage controls deflate real estate costs for households and business?

will investment in wave and nuclear deflate energy and carbon footprint costs?

will investment in education training and health have their own economic benefits?

if we still have unemployment we could have JG to clean up the place

“The same logic underlying Dean Baker’s proposal was used by the French when they brought in a statutory 35-hour working week in February 2000. It was seen as a way of “spreading the work” and reducing their persistently high unemployment rates.

The facts that emerged were that employers did not hire new workers in any great quantity and unemployment remained largely unchanged (as a consequence of this move). ”

You of all people should understand that overall labor demand depends on overall spending decicions in the economy. What was the France’s fiscal stance at the time, tight? Lax? And how can German experience be success if work sharing is such a failure.

And there are other reasons to lower working times. I have seen many people wondering, that who would have quessed 100 years ago in the time of progressive 8-hour day movement, that 100 years later we would still be doing 8 hour days. Why did the progress stop? You know the 8-hour day movement did not demand shorter working times to lower unemployment, it was question of values, and I know many supporters of Frances 35-hour work week do so purely on highly idealistic value reason of improving life quality.

“bosses just increased intensity of work and so 5 days work was performed in 4 days.”

Here is an another thing I don’t understand. You say like it would be a good thing that workforce comes to workplaces just to hang out for 20% of the working time. Even though they do not produce nothing. Even though they waste their time. To me it seems to be low hanging fruit to eliminate this waste of time and give employees more quality time with their friends and families, given that the production levels do not have to be lowered i.e. material consumption levels do not have to suffer. Frances 35-hour workweek did improve productivity to one of the highest in the world.

A Jobs Guarantee ignores the fundamental problem which is that people have been dispossessed (Remember the family farm?) and now even dis-employed (via automation) with their own stolen purchasing power via the government backed/enforced counterfeiting cartel, the banking system.

What about a few years from now (assuming we survive banking till then) when nearly all non-creative work will be done by robots? What good will a trained workforce do then? Or shall we ban further automation?

The problem is not a lack of jobs but a lack of justice.

Several comments:

[1] “Structural unemployment”: This is nonsense. This is simply employers who are not willing to pay enough either to attract the necessary talent or develop it themselves. The counter-argument, that this cannot be done while remaining competitive, is also nonsense. That’s simply a failed business plan, something that happens via the very nature of capitalism. Those who can’t compete, die. And if some product or service simply cannot be built or offered because of this, it’s because to purchasing public does not value it sufficiently, something that is also within the nature of capitalism.

In other words, to call this structural unemployment is simply to blame labor for the failures of the capitalist. Capitalism does not guarantee the success of every business idea.

[2] “Loss of skills”: I have been in the labor force for about 50 years. (I started early.) I have dug ditches, built houses, catered to whims of the rich, driven trucks, built massive business systems, consulted to the kings of industry, and crewed and captained yachts. Anyone looking at my resume would gaze wide-eyed: “You’ve really done all that?” Yes, I have. And in the process, I’ve worked with many thousands of people, and worked for hundreds of bosses.

Whenever I hear this “loss of skills” argument, I think of where in my various and many careers I’ve ever seen this. Certainly I, if anyone, would have seen this somewhere if it exists, and yet I cannot think of a single instance where I’ve encountered this, either in myself, or with those I’ve worked among. Sure, one might get a little rusty-I haven’t ridden a bike for a while; I might be shaky for a outing or two-but skills and proficiency in them are quickly recovered, and done so with an effort miniscule in comparison to the effort required to acquire them the first go around.

I guess my question then would be, is the “loss of skills” argument simply something that seems so intuitively pleasing that one assumes its truth without verifying, or is there actual measured evidence of this? If it’s the former, it needs to be tossed as quite destructive; an insult to the intelligence of workers. If it’s the latter, I’d have to suspect (from my experience, at least) that those doing the measuring were introducing more than a bit of confirmation bias into their work.

_____

Maybe one has to get out into the real word to see these things. Get away from the cloistered intellectualisms of university lecture halls and corporate boardrooms. Anything to break the hard-wired thought patterns that develop from such confinements.

Hell, even playing in a rock and roll band would probably do the trick. 🙂

If one considers the number of working hours as an aggregate them my estimate is that it could be cut in half essentially maintaining actual life standards in the developed countries. I guess half of the work done, both in the private as public sector, is work-for-heath: unavoidably it is converted into heat but produces no information.

In reality things are a bit more complex. First a fairer economic system is to develop. Human development is limited not by lack of energy or materials, but by sectoral greed hijacking the governance of public goods and services. With a fairer economic system is developing collective energy and knowledge could be put at better use than in negative sum games. I will not try to list positive sum games. In a cooperative mindset there is more to do than people capable of.

Benedict@Large: “I guess my question then would be, is the “loss of skills” argument simply something that seems so intuitively pleasing that one assumes its truth without verifying, or is there actual measured evidence of this?”

Evidence? We don’t need no stinking evidence.

Very interesting. I also don’t think Dean Bakers plan is helpful. But on the other hand there was this very interesting article in the Guardian “It’s the 21st century – why are we working so much?” And this is indeed a good question. It seems to me, that a later entry into the labor market with a much more balanced life of leisure & eduction before and an earlier exit of the labor market would be more fitting for the 21st century?

PZ makes a good point. I was thinking myself that it seems odd that the work-week did not continue to decline as technological progress improved productivity enormously. This seems a sociological phenomenon, not a technical one. It does seem today that critical functions (growing food) employ just a small percentage of people, whereas many others (such as those working in Finance) produce nothing of value.

1. Unemployment is an incentive for the employed to work harder.

2. Active poaching of skilled labour discourages investment in training and leads to shortages.

I share many of your sympathies but many of yee lads don’t seem to understand the nature of the Industrial collapse in Europe caused by the postponement of rational investment ever since new nuclear was halted 30 + years ago now as interest on “sovergin debt” reached a point where apparently rational capital creation stuff became too expensive to sustain…..

Here is some of the points from the British first quarter energy bulletin for 2012.

“Indigenous production of fuels in the UK fell by 11.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2012

compared with a year earlier. Production of oil fell by 13.0 per cent whilst gas fell by 14.1 per cent as a result of maintenance work and slowdowns on a number of fields.

Total primary energy consumption for energy uses fell by 2.3 per cent. However, when adjusted to take account of weather differences between 2011 and 2012, primary energy consumption fell by 1.1 per cent.

Of electricity generated in the first quarter of 2012, gas accounted for 27 per cent (its lowest share in the last fourteen years) due to high gas prices, whilst coal accounted for 42 per cent. Nuclear generation accounted for 17 per cent of total electricity generated in the first quarter of 2012, a decrease from the 19 per cent share in the first quarter of 2011.”

The introduction of pure fiat by Goverment rather then exchequer / CB incest is what is needed to stop the waste inherent in the now bank credit hyper inflated envoirment.

They will have to hyper inflate so that all cars will travel with full passengers if at all.

Europe is bleeding energy tokens all over the dance floor.

Need I say , Energy is defined as the ability to do work.

If you look at core or semi core Europe there is a collapse of oil consumption.

With Italy down a massive 15% YoY

Its Diesel demand is even worse (this is a good indicator for commercial & construction actvity)

omrpublic.iea.org/demand/it_dl_ov.pdf

French Diesel and Gasoline demand is diveraging on a massive scale which indicates France is desperatly trying to maintain capital construction at the expense of personel consumption.

Yee MMT guys are 30 years too late.

Nothing can stop this entropy now….. nothing.

The neo – liberal poison was a lethal dose.

PS

If you look at UK vehicle demand they are sustaining along with core Germany what remains of the European market because they are sovergin.

In a world of limited supplies they can simply outbid non sovergin units for oil , LNG and other fuel & raw materials to fill the North Sea void…..which means less for the rest of us – a zero sum game

For example If you look at Jan to May Bus vehicle regs in Europe the UK is the equivalent of France , Italy & Spain combined now!!! so there is a least good substitituion going on in semi – sovergin UK land.

Unskilled Labour with picks and shovels cannot compete with Bulldozers – at least not until the Diesel tank is empty….they simply get in the way.

It is unfathomable why this is not an absolute policy priority and the Euro leaders announce immediate job creation programs through the Eurozone targetted at youth, if they cannot bring themselves to introduce an unconditional job guarantee for all workers.

I think it is fathomable. The conclusion to be drawn from the central empirical fact – lack of urgent policy response – is that European leaders simply do not care all that much about European youth and whether or not they are employed. They see youth unemployment as a fact of life to be managed and socially contained, not a problem to be solved. By analogy, in the United States we have high crime rates and very high incarceration rates compared to many other developed countries. But our leaders do not regard the incarceration rate as an urgent problem needing a solution. They regard it as an ongoing fact of life to be managed. I suspect European leaders increasingly see unemployment the same way.

Most European leaders live in enclaves of the European economy that are economically secure and well-provisioned by consumer supply chains that can continue to function perfectly well even in a society that is not close to full employment. These leaders are well-protected by a variety of policing systems from any social disruptions due to youth misery and disaffection in their own countries or other European countries. They can continue to enjoy their current levels of income indefinitely, even if large masses of the European population fall off the economic map. They will continue to be re-elected since the definition of reality and the financial means of obtaining electoral victory are determined by fellow-elites in media and finance who share the interests of these leaders.

I am increasingly drawn to the following theory of unemployment: the owners of the material factors of production are collectively motivated by the pursuit of profit – that is, by their own satisfaction. As a result, they employ human resources to add value to those factors of production, and distribute the fruits among themselves through exchange. They distribute only as much to the human factors as they need to in order to draw the desired work out of them. However, once those owners have achieved a level of affluence and sated satisfaction beyond which it is difficult or pointless to attempt to draw more satisfaction out the material factors, their aggregate incentive to increase total output diminishes, and they become increasingly focused on preserving what they already have rather than improving their lot. This ownership satiety plateau can occur at a level far below full employment. So there is no reason to think that the ownership class will make it their business to increase output and employment. And if the owners also own the government, there is no reason to think government will make it their business either.

«Most European leaders live in enclaves of the European economy that are economically secure and well-provisioned by consumer supply chains»

That’s rentier enclaves.

«that can continue to function perfectly well even in a society that is not close to full employment.»

That is a rather plausible attitude.

But the big deal is not that «Most European leaders» have that attitude, but that most european and USA voters have it, and just don’t care about those whom they think of as parasitic losers: those poorer than themselves.

The great neo-liberal strategy since about 1980 is to persuade the middle classes that they part of the rentier elite and that both were being exploited by the strapping young bucks and the welfare queens, and their interests were aligned.

With the mirage of making their comfortable future retirements more luxurious the rentier middle classes have been voting for 30 years for higher capital gains and lower wages, for lower taxes for the rich and welfare cuts for the poor, for higher exports of capital and massive imports of labor.

In particular the middle aged and older middle and upper class female voters, for a recent example this piece from the Times (in the UK) about middle class middle aged women voting for a neo-liberal program of cutting welfare wasted on parasites during the biggest recession of the past several decades years, to fund more jobs and tax cuts for themselves:

The Times, 2011-09-17, Janice Turner:

«The C2 women who voted Conservative last time did so because they, in low to middling-paid roles such as nurses, secretaries and carers, believed welfare had grown too generous, that benefits rewarded the do-nothings while they toiled. They hoped the Tories would crack down.»

For a similar report from the USA:

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/aug/18/what-were-they-thinking/

«It all goes back to the “shellacking” Obama took in the 2010 elections. The President’s political advisers studied the numbers and concluded that the voters wanted the government to spend less. This was an arguable interpretation.

Nevertheless, the political advisers believed that elections are decided by middle-of-the-road independent voters, and this group became the target for determining the policies of the next two years.

That explains a lot about the course the President has been taking this year. The political team’s reading of these voters was that to them, a dollar spent by government to create a job is a dollar wasted.

The only thing that carries weight with such swing voters, they decided – in another arguable proposition – is cutting spending.»