I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The structural mismatch propaganda is spreading … again!

Whenever unemployment rises substantially – that is, whenever there is a recession, the conservatives hide out for a while because the rapid rise in joblessness does not resonate with their models of voluntary choice (that is, workers choosing leisure although they can never explain why workers would suddenly get lazy?) or with their claims that structural factors push the unemployment rate up (although welfare policies etc rarely alter much). Of-course, they love it when some “structural” policy changes during a recession which is why they are cock-a-hoop about the decision of the US government to extend unemployment benefits. It has given them some latitude to get back into the debate even if all the data is working against them. But they always oppose the use of fiscal policy and so typically, towards the tail-end of a recession, they attempt to justify the deplorable unemployment levels by playing the “structural card”. We are now seeing that again and I expect the propaganda to spread and proliferate. It should be rejected like the rest of the cant.

On August 26, 2010 the Economist Magazine ran the story – There is more to America’s stubbornly high unemployment rate than just weak demand. Commenting on the US labour market, the article said that:

More than a year into the current economic recovery the unemployment rate remains stuck close to 10%, raising concerns about the kind of sclerosis that continental Europe suffered in the 1980s … Some economists now fret that other barriers besides weak demand stand between workers and jobs, and that high unemployment is partly “structural” in nature.

Apparently, “(u)nemployment has failed to fall in a way consistent with the increase in job openings” which suggests that there are now rising “structural obstacles to jobs growth”.

The author chooses to implicate the extension of unemployment benefits – a claim I covered (refuted) in this recent blog – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments

They say that a “bigger worry is that jobseekers no longer have the skills demanded by employers” and that workers losing jobs in “construction and manufacturing … may struggle to adapt to jobs in more vibrant areas such as education and health services.”

They draw on claims made recently by the IMF and the new president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

The problem with these claims is that it is always difficult to sort out “the cyclical from the structural”.

Demand deficient unemployment occurs when the number of people wanting gainful employment exceeds the number of vacancies being offered. The composition of the unemployed relative to the skills demanded is not the binding constraint.

Alternatively, the classification of unemployment as structural describes unemployment that results from imbalances in the supply of, and demand for, labour in a disaggregated context. A simple case arises which highlights the difference as to which constraint is promoting the unemployment. If at the aggregate level the number of unemployed is equal to the number of vacancies then (abstracting from seasonal and frictional influences) this unemployment would be termed structural.

Structuralists suggest that structural imbalances can originate from both the demand and supply sides of the economy. Technological changes, changes in the pattern of consumption, compositional movements in the labour force and welfare programme distortions are among the pot-pourri of influences listed as promoting the structural shifts.

The distinction between demand deficient and structural unemployment is usually considered important at the policy level. Macro policy will alleviate demand deficient unemployment, while micro policies are needed to redress the demand and supply mismatching characteristic of structural unemployment. In the latter case, macro expansion may be futile and inflationary.

But if structural changes are, in fact, cyclical in nature a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

A few days later (August 26, 2010), the Economist Magazine followed up there earlier article with this one – America’s jobs woes cannot be cured just by waiting for economic recovery.

It just repeated the message of the other article except zeroed in on why fiscal policy is likely to be impotent.

The article said:

The main point of contention is whether policymakers should try to speed up that process with yet more fiscal or monetary stimulus … unemployment is high for other reasons too-ones largely neglected in the current debate. Thanks to the scale and nature of the housing and financial bust, the labour market has almost certainly become less efficient at matching the supply of jobseekers with the demand for workers … if a chunk of America’s unemployment is structural, its policymakers need urgently to think beyond stimulus measures, and also to adopt more targeted policies to help the millions stuck in the wrong place with the wrong skills. Otherwise, even a return to brisk economic growth (something that scarcely looks likely right now) will not be enough to rescue them from the breadline.

This theme was recently taken up by the newly appointed president to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (previously a mainstream professor of economics). In one of his early speeches (August 17, 2010), Narayana Kocherlakota was talking about the relationship between unemployment and job openings which I considered in this blog – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments.

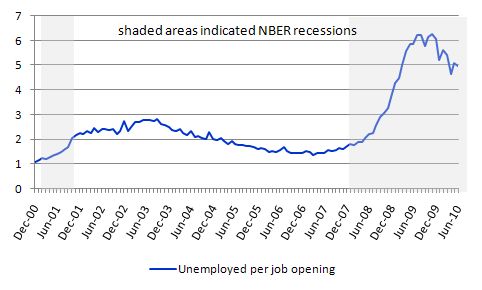

Here is the unemployment to job openings ratio graph again. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics describe the data relating to this graph in this way:

When the recession began in December 2007, there were 1.8 unemployed persons per job opening. The ratio rose to a high of 6.2 unemployed persons per open job, more than twice the highest ratio seen since the JOLTS series began … From the high of 6.2 unemployed persons per job opening in November 2009, the ratio fell to 5.0 in June 2010.

I concluded that the unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there! This is exactly what happens when aggregate demand falls and job openings dry up.

But Kocherlakota has a different take:

Beginning in June 2008, this stable relationship began to break down, as the unemployment rate rose much faster than could be rationalized by the fall in the job openings rate. Over the past year, the relationship has completely shattered. The job openings rate has risen by about 20 percent between July 2009 and June 2010. Under this scenario, we would expect unemployment to fall because people find it easier to get jobs. However, the unemployment rate actually went up slightly over this period.

What does this change in the relationship between job openings and unemployment connote? In a word, mismatch. Firms have jobs, but can’t find appropriate workers. The workers want to work, but can’t find appropriate jobs. There are many possible sources of mismatch-geography, skills, demography-and they are probably all at work. Whatever the source, though, it is hard to see how the Fed can do much to cure this problem. Monetary stimulus has provided conditions so that manufacturing plants want to hire new workers. But the Fed does not have a means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.

Of course, the key question is: How much of the current unemployment rate is really due to mismatch, as opposed to conditions that the Fed can readily ameliorate? The answer seems to be a lot. I mentioned that the relationship between unemployment and job openings was stable from December 2000 through June 2008. Were that stable relationship still in place today, and given the current job opening rate of 2.2 percent, we would have an unemployment rate of closer to 6.5 percent, not 9.5 percent. Most of the existing unemployment represents mismatch that is not readily amenable to monetary policy.

To see the folly of his argument lets consider the evidence (again!). How come whenever we actually look at the facts these neo-liberal arguments start to look shaky? Answer: obvious!

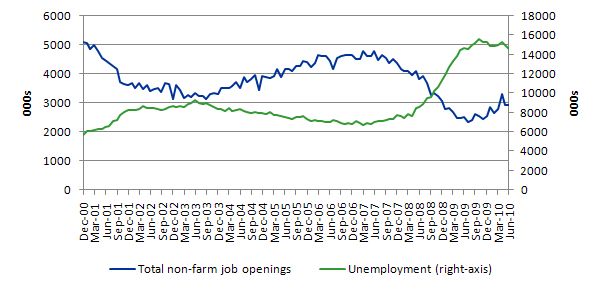

This graph taken from the BLS JOLTS database shows job openings and unemployment from December 2000 to June 2010 (in 000s). Total unemployment (green line) is on the right-axis while total non-farm job openings (blue line) are on the left-axis. You can see that as the economy faltered job openings collapsed unemployment rose but not as much as would be predicted by the employment losses.

Why? Answer: Some workers gave up looking and left the labour force. As the job openings increased again in recent months, unemployment has been steady because the discouraged workers are now re-entering the labour force again.

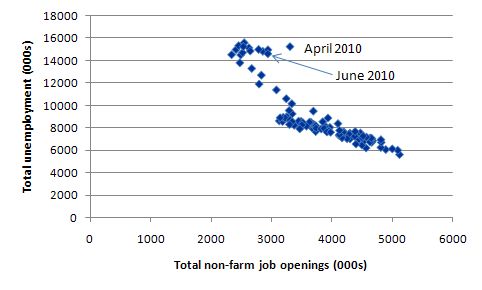

The following scatter graph allows you to see the shift in the job openings-unemployment relationship. As economic growth showed signs of resuming labour participation rates increased and this pushed unemployment up as employment growth resumed. Those cyclical adjustments always accompany the early stages of a recovery. This is a reflection that the deficient demand not only increases unemployment in the downturn but also pushed people out of the labour force as they give up actively looking for work that is not there. These hidden unemployed workers re-enter the labour force as the probability of getting a job (in their mind) increases.

So this pattern is entirely normal. It seemed that back in May, Kocherlakota also thought this was happening too.

On May 13, 2010 he delivered an address entitled – Economic Outlook and Economic Choices and said this:

Last Friday, we learned that firms reported that the economy had created nearly 300,000 jobs last month. At the same time, the unemployment rate rose to 9.9 percent in April from 9.7 percent in March. How can both of these take place at the same time? To understand this, we have to get into the technicalities of how the unemployment rate is calculated. The government asks a large group of people: Are you working? Or, if you’re not, have you looked for work in the past four weeks? The total number of people engaged in one of these two activities-working or looking for work-is called the labor force. The unemployment rate is the fraction of the labor force who don’t have a job, but are looking for work.

So, what happened in April is that the growth rate of the labor force was actually faster than the growth rate of the employed. My own tentative interpretation is that both of these pieces of information-the increase in the number of jobs and the increase in the size of the labor force-actually indicate that the labor market is starting to function better.

Indeed! By August he is pushing the standard neo-liberal line. I guess he was looking in the mirror a bit much and admiring his president of the Fed sign on his desk and decided he better toe the line!

At any rate, his two positions do not square.

Paul Krugman on August 24 took the banker to task in this article – Hangover Theory At The Fed. I considered Krugman’s argument to be excellent (for once) – which is probably because he stayed clear of discussing monetary and fiscal issues.

Krugman said:

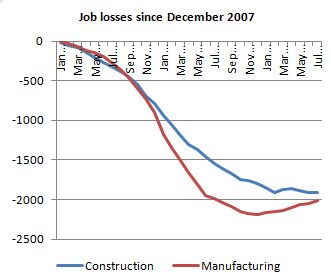

Kocherlakota would have us believe that there’s a big problem of mismatch because manufacturing is trying to hire, while construction has slumped. But here’s the employment reality … [and then the following graph appears] …

Which leads him to conclude that:

Manufacturing employment has slumped, not risen – in fact, it has fallen more than construction employment. The problem is lack of overall demand, not worker mismatch.

Unfortunately, we’re not having an academic discussion here: right now, bad theory – theory completely at odds with actual experience – is having a real effect in blocking action.

My friends at the IMF are also running this line at present. In their publication – United States: Selected Issues Paper they conclude that:

… equilibrium unemployment rates increased by about 1½ percentage points in the United States following the Great Recession, which calls for some policy action …

So they are claiming that the NAIRU has risen. They talk about mismatches being “near or at peak historical levels in numerous states, mostly the ones with a large manufacturing sector. States that had specific characteristics (e.g., Delaware-a financial hub; Hawaii-highly reliant on tourism; and Michigan-an auto hub) experienced disproportionate increases in skill mismatches.”

This is a question I dealt with in my PhD research. I first started this work in the early 1980s and I noted at the time that there were two striking developments in economics in this period. On the one hand, a major theoretical revolution was becoming entrenched in macroeconomics; while on the other hand, unemployment rates had risen and were persisting at the highest levels known in the Post World War II period. The two developments were, in my view, inconsistent.

In the 1970’s, the long-standing dominance of so-called Keynesian macroeconomic theory and policy was abandoned by a large number of economists, particularly those in academic institutions in the United States. Alan Blinder noted that by:

… about 1980, it was hard to find an American macroeconomist under the age of 40 who professed to be a Keynesian. That was an astonishing turnabout in less than a decade, an intellectual revolution for sure.

The rise in acceptance of Monetarism and its new classical counterpart was not based on an empirical rejection of the Keynesian orthodoxy, but was instead, according to Blinder, “a triumph of a priori theorising over empiricism, of intellectual aesthetics over observation and, in some measure, of conservative ideology over liberalism. It was not, in a word, a Kuhnian scientific revolution”.

The resurgence of pre-Keynesian monetary thinking was aided by empirical estimates of the Phillips curve – the relationship between unemployment and inflation.

The natural rate of unemployment hypothesis (NRH) became a central tenet of the anti-Keynesian stance. Prior to 1970, the Keynesian model considered real output (income) and employment as being demand-determined in the short-run, with price inflation being explained by a negatively sloped Phillip’s curve, relating the percentage change in nominal wages, and, via a productivity function, the inflation rate to the rate of unemployment.

The policy questions of the day were often cast in terms of a trade-off between output (unemployment) and inflation. Policy-makers were supposed to choose between alternative mixes of unemployment and inflation subject to a socially-optimal level of unemployment and inflation.

During this period, the Phillip’s curve was considered to be negatively sloped in both the short-run and the long-run. The first major challenge to this view was provided by Friedman’s 1968 address to the American Economic Association and the related article by Edmund Phelps (1968). In fact, Friedman (1968: page 60) first stated that:

… there is no long-run, stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

These papers stimulated a new wave of econometric research, which focused on the estimate of the coefficient on the price expectations term in the wage adjustment function. Various models were constructed to “prove” Friedman’s conclusion.

At the same time the economic performance of the OECD economies was failing badly. In 1972, Australia’s inflation rate was 6.2 per cent, but following the first OPEC oil shock in 1974, aided by some large wage increases, the inflation rate reached 15.4 per cent in 1974, and 17 per cent in 1975.

By the end of the 1970s, despite a period of subdued activity and rising unemployment, the inflation rate was still high in relation to Australia’s trading partners at 9.2 per cent.

By this time, any Keynesian remedies proposed to reduce unemployment were met with derision from the bulk of the profession who had embraced the NRH and its policy implications. Yet despite the predominance of Monetarist thought there was very little evidence presented to substantiate these effects in any economy in the world.

The NRH reinstated the early classical idea of a rigid natural level of output and employment. Essentially, the NRH asserted that in the long-run there was no trade-off between inflation and unemployment, because the economy would always tend back to a given NRU, no matter what had happened to the economy over the course of time.

Time and the path the economy traced through time were thus irrelevant. Only microeconomic changes would cause the NRU to change. Accordingly, the policy debate became increasingly concentrated on deregulation, privatisation, and reductions in the provisions of the Welfare State.

This period was the dawning of the age of neo-liberalism that we are still trapped in.

At the time, as a graduate student I considered that the NRU concept really only belonged in models of perpetual full employment, which is to be expected given the neo-classical inheritance. The NRH was merely a standard prediction from the orthodox competitive model, which lacked empirical substance.

It was not difficult to find empirical evidence which was contrary to the edicts of the NRH – for example, the quit rate analysis I presented in this recent blog – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments.

In the real world, booms in activity stimulates on-the-job training opportunities and raises potential output above the level that would have persisted had the economy remained at low levels of activity. Alternatively, as activity falls due to demand failure, both training opportunities decline and actual skills are lost, as workers lie idle. The potential capacity level falls as a result.

Alan Blinder concluded in 1988 that there is:

… no natural level of employment … the equilibrium level depends on what came before.

At the time, I started to work on the idea that we should expect aggregate demand factors to affect the estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, given that this concept merely defines the unemployment level which is consistent with an unchanging inflation rate.

This idea became known as the hysteresis hypothesis (HH) and was the major early thrust of my research work. It was an exciting retaliation against Monetarist orthodoxy. Models, which are subject to hysteresis properties, postulate that the equilibrium of the economy is not independent of the past track that the economy has followed.

Blinder said that in hysteresis models:

… in which the economy’s equilibrium state depends on the path we follow to get there … bring Keynesian economics back with a vengeance.

I wrote at the time that hysteresis turns the classical truism of supply creating demand on its head. In essence, the fiscal authority is seen to be able to permanently increase the level of employment (for given labour-force aggregates) up to some amount dictated by frictions, through expansionary policy stimulation of aggregate demand. Blinder called it a “neat reversal of Say’s Law, … [where] … demand creates its own supply.”

Hysteresis went beyond the simple Keynesian (passive) vision of supply. In hysteresis models the supply-side of the economy adjusts to demand changes such that in times of low demand, labour skill declines and potential output shrinks. Similarly, upgrading of labour skill and potential output accompanies an increase in demand. Accordingly, the concept of a natural rate of unemployment would only make sense in an economy that that had experienced stable, full employment aggregate demand levels for a long period.

In 1987 I published a paper in the Australian Economic Papers – The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroequilibrium Unemployment Rate – which was the first Australian study of hysteresis and one of the first international studies. My technical papers were published in 1985 which pre-dates the work of Blanchard and Summers who published in 1986 on the topic and became popular as a result. The editorial process for the Australian Economic Papers was very slow and I missed out on the “early mover advantage” in this emerging literature. I think back now on that period and wonder why I cared about things like that (being beaten to the punch!).

The motivation was clearly that the policy orientation in the UK, the US and in Australia was and remains based on the view that inflation is the basic constraint on expansion (and fuller employment).

The popular belief is that fiscal and monetary policy can no longer attain unemployment rates common in the sixties without ever-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment (NRU) which is the rate of unemployment consistent with stable inflation is considered to have risen over time.

The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is a less rigorous version of the NRU but concurs that a particular, cyclically stable unemployment rate coincides with stable inflation. Labour force compositional changes, government welfare payments, trade-union wage goals among other “structural” influences were all implicated in the rising estimates of the inflationary constraint.

The NAIRU achieved such rapid status among the profession as a policy-conditioning concept that I thought it warranted close scrutiny.

My basic proposition was that persistently weak aggregate demand creates a labour market, which mimics features conventionally associated with structural problems.

The specific hypothesis I examined was whether the equilibrium unemployment rate is a direct function of the actual unemployment rate and hence the business cycle. That is the hysteresis effect.

By developing an understanding of the way the labour market adjusts to swings in aggregate demand and generates hysteresis, providing a strong conceptual and empirical basis for advocating counter-stabilising fiscal policy (aggregate policy expansion in a downturn). So 23 years later I am still at it!

So while it might look like the degree of slack necessary to control inflation may have increased, the underlying cyclical labour market processes that are at work in a downturn can be exploited by appropriate demand policies to reduce the steady state unemployment rate.

In that work I outlined a conceptual unemployment rate, which is associated with price stability, in that it temporarily constrains the wage demands of the employed and balances the competing distributional claims on output.

I introduced a new term the macroequilibrium unemployment rate (the MRU) which I noted was, importantly, sensitive to the cycle due to the impact of the cyclical labour market adjustments on the ability of the employed to achieve their wage demands. In this sense, the MRU is distinguished from the conventional steady state unemployment rate, the NAIRU, which is not conceived to be cyclically variable.

What I wanted to show was that there was an interaction between the actual and MRU which would establish the presence of the hysteresis effect.

To be clear – the significance of hysteresis, if it exists, is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy.

The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate. That is why I chose to use the term MRU, as the non-inflationary unemployment rate, as distinct from the NAIRU, to highlight the hysteresis mechanism.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

So why would there be some unemployment rate that is consistent with stable inflation. Remember this is a non Job Guarantee world. The introduction of a JG would change things considerably (more favourably).

There is an extensive literature that links the concept of structural imbalance to wage and price inflation. A non-inflationary unemployment rate can be defined which is sensitive to the cycle.

You can view inflation as being the product of incompatible distributional claims on available income. So when nominal aggregate demand is growing too quickly, something has to give in real terms for that spending growth to be compatible with the real capacity of the economy to absorb the spending.

Unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital. That was Kalecki’s argument which I considered in the blog – Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment.

A lull in the wage-price spiral could thus be termed a macroequilibrium state in the limited sense that inflation is stable. The implied unemployment rate under this concept of inflation is termed in this paper the MRU and has no connotations of voluntary maximising individual behaviour which underpins the NAIRU concept that is at the core of mainstream macroeconomics.

Wage demands are thus inversely related to the actual number of unemployed who are potential substitutes for those currently employed. Increasing structural imbalance (via cyclical non-wage labour market adjustment) drives a wedge between potential and actual excess labour supply, and to some degree, insulates the wage demands of the employed from the cycle. The more rapid the cyclical adjustment, the higher is the unemployment rate associated with price stability.

Stimulating job growth can decrease the wedge because the unemployed develop new and relevant skills and experience. These upgrading effects provide an opportunity for real growth to occur as the cycle reduces the MRU.

Why will firms employ those without skills? An important reason is that hiring standards drop as the upturn begins. Rather than disturb wage structures firms offer entry-level jobs as training positions.

It is difficult to associate wage demands (in excess of current money wages) with the workforce. While the increased training opportunities increase the threat to those who were insulated in the recession this is offset to some degree by the reduced probability of becoming unemployed.

In 1980, the late James Tobin succinctly summed up the extant literature on the NAIRU at the time:

It is possible that there is no NAIRU, no natural rate, except one that floats with history. It is just possible that the direction the economy is moving in is at least as important a determination of acceleration and deceleration as its level. These possibilities should give policy makers pause as they embark on yet another application of the orthodox demand management cure for inflation.

The subsequent empirical work I did and which has since been built on by others has blown the NAIRU concept out of the water. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

Even the IMF report I cited above suggests that the (quote from the Economist):

… structural barriers to employment growth may be transitory and could fade as the economy recovers. The rate at which workers leave unemployment is uniformly weak across sectors, suggesting that skills mismatch is not yet as important as weak demand in delaying hiring. The absence of price and wage pressures points to plenty of slack in the labour market.

The NAIRU concept does not stack up theoretically or empirically. It is well established that changing labour market imbalances reflect cyclical adjustment processes which render any estimated macroequilibrium unemployment rate to be cyclically sensitive and therefore not the basis of an inflation constraint.

The NAIRU hypothesis suggests that any aggregate policy attempt to permanently reduce the unemployment rate below the current natural rate inevitably is futile and leads to ever-accelerating inflation. The vertical Phillips curve is accepted by most economists, monetarists and Keynesians alike.

However, the empirical world supports the notion that imbalances reverse when aggregate demand regains strength. The last thing we should be doing at present is to abandon job creation policies and start thinking that training programs and worker-attitude-correction strategies will produce any jobs.

I will finish by repeating this quote from Michael Piore (1979: 10):

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original) [Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., White Plains]

Technical section – measuring the NAIRU

For those interested in some of the technical issues this section might be useful.

I started that research by asking the question:

Could the increasing NAIRU estimates reflect a decade or more of high actual unemployment rates and restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and hence, not necessarily be indicative of increasing structural impediments in the labour market?

To motivate the discussion I noted that the NAIRU is popularly derived by solving a system of difference equations (wage and price) for their steady state properties (steady inflation).

The wage adjustment process is written as function of excess demand for labour, and usually, the unemployment rate is used as a negative proxy for the excess demand.

Consequently, two relationships must be captured. First, the wage-excess demand relationship and, second, the unemployment-excess demand relationship.

Combining these relations produces the wage adjustment function, from which the NAIRU is estimated.

Here is a little model for those inclined that demonstrates the case.

In the context of the discussion I started by assuming a very simple (linear) wage model:

Eqn 3-1 w_dot = a1 + a2.Z + a3.p_dot_e

where w_dot is money wage inflation, Z is the excess demand for labour, p_dot_e is the term for inflation expectations and a1 reflects forces which promote real wage growth independent of Z (like, productivity growth and variations in profit margins, both of which could be cyclically sensitive).

The unemployment-excess demand equation is

Eqn 3-2 u = b1 – Z

where u is the unemployment rate, b1 is the measure of frictional and/or structural unemployment (that is, labour market rigidities), and Z is scaled so that its coefficient is unity.

Summing (3-1) and (3-2) gives

Eqn 3-3 w_dot = a4 – a2 + a3.p_dot_e

with a4 = a1 + a2.b1. Clearly, a4 is a composite of structural and nominal demand influences, although separate identification is difficult.

Solving for the steady-state unemployment rate, u* yields:

Eqn 3-4 u* = (a1/a2) + b1

which shows the composite influence on the conventional measures of the NAIRU.

The strict NRU concept, faithful to Friedman insulates the NRU from aggregate demand influences. In this case a1 = g_dot (productivity growth) and the influence of other variables like changing mark-ups is not accounted for.

The real world evidence shows that a1 is cyclically unstable and does not exclusively indicate productivity growth. Even if a1 = g_dot, endogenous productivity changes (associated with labour hoarding, for example) allow the cycle to influence the estimated NAIRU.

In English, this model is a typical type that is used in NAIRU discussions. It is clear that even the most simple interpretation allows the business cycle to influence the estimated NAIRU (u*).

Given that rising NAIRU estimates that the neo-liberals come up with typically occur when there is excess productive capacity, high unemployment rates, slack demand and low productivity growth it is plausible that these increases reflect cyclical forces rather than basic structural labour market changes.

There is a strong body of literature pointing to that proposition that the neo-liberals never choose to acknowledge. Never let some facts get in the way of their theory is their well-practised approach!. If the data suggest the theory is bunk conclude always that the data is wrong is their other defense.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – and I will try to make it harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

“Apparently, “(u)nemployment has failed to fall in a way consistent with the increase in job openings” which suggests that there are now rising “structural obstacles to jobs growth”.

I’ve read this argument before.

Is it actually possible to determine to a near-certainty exactly how many jobs are on offer at a given point in time? Isn’t it fairly normal practice for the same job to be advertised more than once through different agencies and media?

It strikes me reading this and the counter arguments and trying to maintain an open mind, that the economics debate is generally distilled into a ‘chicken and egg’ discussion – which came first supply or demand.

Isn’t it actually the case that it is a circle, and what happens is that friction builds up at certain points in that circle. In the 70s we had supply side friction in terms of oil shock and overly restrictive regulations that gave too much power to labour over profits. Now that has been eliminated and the friction is building up on the demand side of the circle.

If the game to make sure that the circle has just the correct amount of friction at all the points so that the circle doesn’t get too large because its spinning too fast, or too small because its spinning too slow.

Dr. Mitchell,

I am relatively new to MMT economics and find it fascinating, and have begun regularly reading you, Randy Wray, Marshall Auerback, Warren Mosler, etc. I have no formal economics training and am still learning. A commenter to Paul Krugman’s latest piece says the following: “the reason why bond yields are lower today than they were in early 2009, is not because the markets have determined that the stimulus package was’s a bad solution for the economy. It’s because there is a lack of other safe places to park one’s money. What would have happened to the 10 year treasury interest rate if there had not been a European debt crises? Money moving out of European bonds meant there was more demand for US Gov’t Bonds and the increase demand contributed to the lower rates. There is nothing to say that our interest rates still won’t sky rocket once investors decide to move their money into more productive investments. The problem of higher rates in the US could still happen when it’s time for the Gov’t to roll over the debt.” What is the response to this argument? I understand that the government does not actually need to issue Treasuries, as that does not actually “fund” government spending. But the government does in fact continue to issue Treasuries as a dollar for dollar set-off to deficit spending. Given that the government does actually issue the debt, isn’t it possible for rates to rise as this commenter suggests? Thanks.

Yes Neil it is a chicken and egg discussion.

As you so aptly point out though it is a circuit which we live in the middle of. Today the matching of supply and demand requires a look at all the factors. Where neoliberals fail is in their almost complete abandonment of the demand side as Bill so routinely skewers.

The economy, it seems to me, can be modeled very closely to our circulatory system, which is something I study professionally. Interestingly enough many people talk about our circulatory system as well as if the supply side (the heart) is where the control center is. Its not. The heart responds to the demands of the cells throughout the body. The heart, evolved as an answer to the demand of more complex organisms. There are organisms without pumps. Respiration happens in many simple organisms without a heart and blood. There are no hearts without organisms.

The idea of money is another area where I think there is some fundamental misperceptions. Many talk as if money was “discovered”. As if someone centuries ago was walking on the road and saw something shiny and said “Hey I can go get some wheat and a tunic with this!!!” In fact money was created, it was an idea thought of “out of thin air”. There are no restrictions on money, only on resources.

I like your analogy of a spinning circle and the speed at which it spins affecting the size of it.

“In fact money was created, it was an idea thought of “out of thin air”. ”

An abstract concept I see it as. Indeed an idea. Gold or iron bars or seashells may once have been money but the value lay in the idea being represented by the physical lump of soft yellow or hard blackened metal or the dead mollusc, not in the physical object itself. Which is why some people’s argument that the only true monetary value that exists lies in an ounce of gold seems silly to me.

… and yet the Austrians keep trying to flog Mises’ regression theory to explain the existence of money.

They really don’t get it.

Perhaps the effects of sweat-shop employment in Asia and Africa has created a new factor in Western unemployment rates. The US has enjoyed remarkably low unemployment for many years and while it has now hit 9.6% this is hardly worse than many European countries in good times. The PIIGS and France seem to rarely achieve better than 7% and I wonder if this reflects a certain European contentedness with the level of unemployment benefits or worker attitude to being out of work. One thing that seems fairly obvious however is that the more capitalist economies utilise labour better over the business cycle but the high Eurozone unemployment has always baffled me.

Ahhh more classic stock flow consistency……..

Considering working one hour in the week of the survey counts a person as being employed I’d hardly be calling 5% or so unemployment “remarkably low”.

Those genuinely unable to work whould be NILF and not part of the equation and those looking for work should simply be in transition from their JG position to a higher paying position in the private sector.

It is pleasing to me that Bill utilizes the hysteresis concept developed by Soviet mathematicians and used extensively by many scientific disciplines. It is a concept I utilize in my own work as one relationship of the inertia entropy during the variation mechanism of occurrence. Hysteresis is the inertia entropy of motion and fluctuation is the inertia entropy of vibration during an impact (shock) of occurrence and its feedback of recovery process of reaction.

I reckon we should look at all categories of non-employment, especially when comparing different countries. An unemployment index can only be used as a relative guide. Unemployment numbers are notoriously manipulated by politicians, eager to produce a desired number.

I would like to be looking at % of available workforce in full time work, (With part time and short week workers aggregated into full time units). I doubt that is the number being bandied around.

I’d also like to know the % of available workers in the population. Just to make sure they don’t create new categories for unavailable workers (e.g. Changes in retirement age, disability, childcare or students). Illegals is another huge missing, they contribute to the economy a lot.

These numbers show partial truth only. If we ever get better numbers the picture might look completely different.