Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday quiz – April 14, 2012 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Central banks provide reserves to the commercial banking system usually at some penalty rate. However, this compromises their capacity to target a given monetary policy rate.

The answer is True.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provide enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system could be impaired and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements that might be in place).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the clearing requirements from other sources (other banks etc) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to that involved in the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and to meet the banks’ own desires.

Now the question seeks to link the penalty rate that the central bank charges for providing reserves to the banks and the central bank’s target rate. The wider the spread between these rates the more difficult does it become for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target (policy) rate.

Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.

So if the central bank really wanted to put the screws on commercial bank lending via increasing the penalty rate, it would have to be prepared to lift its target rate in close correspondence. In other words, its monetary policy stance becomes beholden to the discount window settings.

The best answer was True because the central bank cannot operate with wide divergences between the penalty rate and the target rate and it is likely that the former would have to rise significantly to choke private bank credit creation.

You might like to read this blogs for further information:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Money multiplier – missing feared dead

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- US federal reserve governor is part of the problem

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

If the real interest rate (difference between nominal interest rate and inflation) is constant, then a currency-isuing government, which matches its net spending $-for-$ with debt issuance, could double its budget deficit without pushing up the public debt ratio.

The answer is True.

Again, this question requires a careful reading and a careful association of concepts to make sure they are commensurate. There are two concepts that are central to the question: (a) a rising budget deficit – which is a flow and not scaled by GDP in this case; and (b) a rising public debt ratio which by construction (as a ratio) is scaled by GDP.

So the two concepts are not commensurate although they are related in some way.

A rising budget deficit does not necessary lead to a rising public debt ratio. You might like to refresh your understanding of these concepts by reading this blog – Saturday Quiz – March 6, 2010 – answers and discussion.

While the mainstream macroeconomics thinks that a sovereign government is revenue-constrained and is subject to the government budget constraint, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue.

The mainstream framework for analysing the so-called “financing” choices faced by a government (taxation, debt-issuance, money creation) – the government budget constraint – is written as:

![]()

Which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

Remember, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So from the perspective of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

For the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

That interpretation is inapplicable (and wrong) when applied to a sovereign government that issues its own currency.

But the accounting relationship can be manipulated to provide an expression linking deficits and changes in the public debt ratio.

The following equation expresses the relationships above as proportions of GDP:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP. A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. If inflation is maintained at a rate equal to the interest rate then the real interest rate is constant.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

So if r = 0, and g = 2, the primary deficit ratio could equal 2 per cent (of GDP) and the public debt ratio would be unchanged. Doubling the primary deficit to 4 per cent would require g to rise to 4 for the public debt ratio to remain unchanged. That is entirely possible.

So a nation running a primary deficit can obviously reduce its public debt ratio over time or hold them constant if growth is stimulated. Further, you can see that even with a rising primary deficit, if output growth (g) is sufficiently greater than the real interest rate (r) then the debt ratio can fall from its value last period.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Clearly, the real growth rate has limits and that would limit the ability of a government (that voluntarily issues debt) to hold the debt ratio constant while expanding its budget deficit as a proportion of GDP.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

The wage share in national income in many nations has fallen significantly over the neo-liberal period which signals that the real standard of living for workers has been falling.

The answer is False.

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP. Economists differentiate between nominal GDP ($GDP), which is total output produced at market prices and real GDP (GDP), which is the actual physical equivalent of the nominal GDP. We will come back to that distinction soon.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. Stocks (L) become flows if it is multiplied by a flow variable (W). So the wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period.

So the wage bill = W.L

The wage share is just the total labour costs expressed as a proportion of $GDP – (W.L)/$GDP in nominal terms, usually expressed as a percentage. We can actually break this down further.

Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP per person employed per period. Using the symbols already defined this can be written as:

LP = GDP/L

so it tells us what real output (GDP) each labour unit that is added to production produces on average.

We can also define another term that is regularly used in the media – the real wage – which is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

We might consider the aggregate price level to be measured by the consumer price index (CPI) although there are huge debates about that. But in a sense, this macroeconomic price level doesn’t exist but represents some abstract measure of the general movement in all prices in the economy.

The real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command and is obviously influenced by the level of W and the price level. For a given W, the lower is P the greater the purchasing power of the nominal wage and so the higher is the real wage (w).

We write the real wage (w) as W/P. So if W = 10 and P = 1, then the real wage (w) = 10 meaning that the current wage will buy 10 units of real output. If P rose to 2 then w = 5, meaning the real wage was now cut by one-half.

So the proposition in the question – that a declining wage share does not mean the real standard of living for workers is falling – true.

Irrespective of what happens to the wage share, as long as the real wage is rising, material standards of living will be rising (other things equal). That is, a declining wage share per se doesn’t denote a decline in workers’ living standards.

What it tells us is that a rising proportion of national income is going to profits (non-wages). But that rising proportion could be in relation to an overall expanding pie.

A declining wage share is consistent with growth in the real wage which is slower than the growth in labour productivity. If the real wage is growing but labour productivity is growing faster, then the wage share will fall.

A declining wage share driven by a real wage falling (and labour productivity at least not falling by as much) would signify a decline in living standards but that is because the real wage is falling.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The origins of the economic crisis

- Saturday Quiz – May 15, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Calling Planet Earth – they will print low

Question 3:

The Eurozone Troika’s strategy for Greece is that domestic deflation will spark an export boom and provide the capacity for the government to run primary surpluses without compromising real economic growth. Although an export boom is unlikely, given current circumstances, if Greece actually achieved positive net exports then the government could push for a primary budget surplus knowing it will not compromise growth.

The answer is False.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

From an accounting sense, if the external sector goes into surplus (positive net exports) there is scope for the government balance to move into surplus without compromising growth as long as the external position more than offsets any actual private domestic sector net saving.

In that sense, the IMF strategy requires more than positive net exports.

Skip the next section explaining the balances if you are familiar with the derivation. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced.

Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive – that is net spending injection – providing a boost to domestic production and income generation.

The extent to which this allows the government to run a surplus depends on the private domestic sector’s spending decisions (overall). If the private domestic sector runs a deficit, then the Troika’s strategy will work – inasmuch as the goal is to reduce the budget deficit without compromising growth.

But this strategy would be unsustainable as it would require the private domestic sector overall to continually increase its indebtedness.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to increase its overall saving and is successful in doing so. With the government contracting (and going into surplus), the only way the private domestic sector could successfully net save is if the injection from the external sector offsett the drain from the domestic sector (public and private). Otherwise, income will decline and both the government and private domestic sector will find it difficult to reduce their net spending positions.

Take a balanced budget position, then income will decline unless the private domestic sector’s saving overall is just equal to the external surplus. If the private domestic sector tried to push its position further into surplus then the following story might unfold.

Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public budget balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the budget into deficit.

So the external position has to be sufficiently strong enough to offset the domestic drains on expenditure. For Greece at present that is clearly not the case and demonstrates why the Troika’s strategy is failing.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Premium Question 5:

Assume that inflation is stable, there is excess productive capacity, and the central bank maintains its current interest rate target. If on average the government collects an income tax of 20 cents in the dollar, then total tax revenue will rise by 0.20 times $x if government spending increases (once and for all) by $X dollars and private investment and exports remain unchanged.

The answer is False.

This question relates to the concept of a spending multiplier and the relationship between spending injections and spending leakages. It is designed to help you think about how the automatic stabilisers linked to tax revenue respond to growth.

We have made the question easy by assuming that only government spending changes (exogenously) in period one and then remains unchanged after that – that is, a once and for all increase.

Aggregate demand drives output which then generates incomes (via payments to the productive inputs). Accordingly, what is spent will generate income in that period which is available for use. The uses are further consumption; paying taxes and/or buying imports.

We consider imports as a separate category (even though they reflect consumption, investment and government spending decisions) because they constitute spending which does not recycle back into the production process. They are thus considered to be “leakages” from the expenditure system.

So if for every dollar produced and paid out as income, if the economy imports around 20 cents in the dollar, then only 80 cents is available within the system for spending in subsequent periods excluding taxation considerations.

However there are two other “leakages” which arise from domestic sources – saving and taxation. Take taxation first. When income is produced, the households end up with less than they are paid out in gross terms because the government levies a tax. So the income concept available for subsequent spending is called disposable income (Yd).

In the example we assumed an average tax rate of 20 cents in the dollar is levied (which is equivalent to a proportional tax rate of 0.20). So if $100 of new income is generated, $20 goes to taxation and Yd is $80 (what is left). So taxation (T) is a “leakage” from the expenditure system in the same way as imports are.

You were induced to think along those lines. The relevant issue to resolve though is – What is the new income generated? The concept of the spending multiplier tells us that the final change in income will exceed the initial injection (in the question $X dollars).

Finally consider saving. Households (consumers) make decisions to spend a proportion of their disposable income. The amount of each dollar they spent at the margin (that is, how much of every extra dollar to they consume) is called the marginal propensity to consume. If that is 0.80 then they spent 80 cents in every dollar of disposable income.

So if total disposable income is $80 (after taxation of 20 cents in the dollar is collected) then consumption (C) will be 0.80 times $80 which is $64 and saving will be the residual – $26. Saving (S) is also a “leakage” from the expenditure system.

It is easy to see that for every $100 produced, the income that is generated and distributed results in $64 in consumption and $36 in leakages which do not cycle back into spending.

For income to remain at the higher level (after the extra $100 is created)in the next period the $36 has to be made up by what economists call “injections” which in these sorts of models comprise the sum of investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X). The injections are seen as coming from “outside” the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).

For GDP to be stable injections have to equal leakages (this can be converted into growth terms to the same effect). The national accounting statements that we have discussed previous such that the government deficit (surplus) equals $-for-$ the non-government surplus (deficit) and those that decompose the non-government sector in the external and private domestic sectors is derived from these relationships.

So imagine there is a certain level of income being produced – its value is immaterial. Imagine that the central bank sees no inflation risk and so interest rates are stable as are exchange rates (these simplifications are to to eliminate unnecessary complexity).

The question then is: what would happen if government increased spending by, say, $100? This is the terrain of the multiplier. If aggregate demand increases drive higher output and income increases then the question is by how much?

The spending multiplier is defined as the change in real income that results from a dollar change in exogenous aggregate demand (so one of G, I or X). We could complicate this by having autonomous consumption as well but the principle is not altered.

So the starting point is to define the consumption relationship. The most simple is a proportional relationship to disposable income (Yd). So we might write it as C = c*Yd – where little c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) or the fraction of every dollar of disposable income consumed. We will use c = 0.8.

The * sign denotes multiplication. You can do this example in an spreadsheet if you like.

Our tax relationship is already defined above – so T = tY. The little t is the marginal tax rate which in this case is the proportional rate (assume it is 0.2). Note here taxes are taken out of total income (Y) which then defines disposable income.

So Yd = (1-t) times Y or Yd = (1-0.2)*Y = 0.8*Y

If imports (M) are 20 per cent of total income (Y) then the relationship is M = m*Y where little m is the marginal propensity to import or the economy will increase imports by 20 cents for every real GDP dollar produced.

If you understand all that then the explanation of the multiplier follows logically. Imagine that government spending went up by $100 and the change in real national income is $179. Then the multiplier is the ratio (denoted k) of the Change in Total Income to the Change in government spending.

Thus k = $179/$100 = 1.79.

This says that for every dollar the government spends total real GDP will rise by $1.79 after taking into account the leakages from taxation, saving and imports.

When we conduct this thought experiment we are assuming the other autonomous expenditure components (I and X) are unchanged.

But the important point is to understand why the process generates a multiplier value of 1.79.

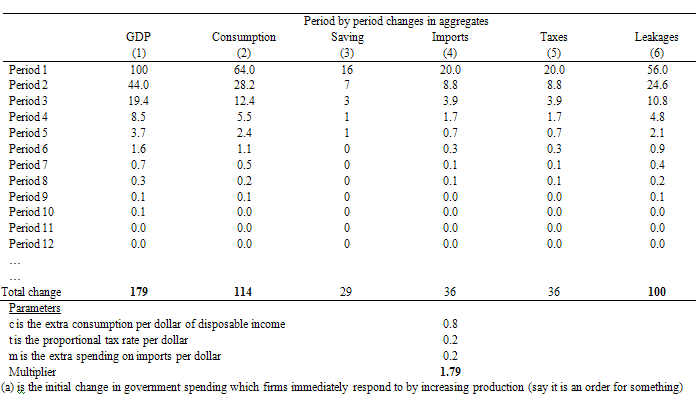

Here is a spreadsheet table I produced as a basis of the explanation. You might want to click it and then print it off if you are having trouble following the period by period flows.

So at the start of Period 1, the government increases spending by $100. The Table then traces out the changes that occur in the macroeconomic aggregates that follow this increase in spending (and “injection” of $100). The total change in real GDP (Column 1) will then tell us the multiplier value (although there is a simple formula that can compute it). The parameters which drive the individual flows are shown at the bottom of the table.

Note I have left out the full period adjustment – only showing up to Period 12. After that the adjustments are tiny until they peter out to zero.

Firms initially react to the $100 order from government at the beginning of the process of change. They increase output (assuming no change in inventories) and generate an extra $100 in income as a consequence which is the 100 change in GDP in Column [1].

The government taxes this income increase at 20 cents in the dollar (t = 0.20) and so disposable income only rises by $80 (Column 5).

There is a saying that one person’s income is another person’s expenditure and so the more the latter spends the more the former will receive and spend in turn – repeating the process.

Households spend 80 cents of every disposable dollar they receive which means that consumption rises by $64 in response to the rise in production/income. Households also save $16 of disposable income as a residual.

Imports also rise by $20 given that every dollar of GDP leads to a 20 cents increase imports (by assumption here) and this spending is lost from the spending stream in the next period.

So the initial rise in government spending has induced new consumption spending of $64. The workers who earned that income spend it and the production system responds. But remember $20 was lost from the spending stream via imports so the second period spending increase is $44. Firms react and generate and extra $44 to meet the increase in aggregate demand.

And so the process continues with each period seeing a smaller and smaller induced spending effect (via consumption) because the leakages are draining the spending that gets recycled into increased production.

Eventually the process stops and income reaches its new “equilibrium” level in response to the step-increase of $100 in government spending. Note I haven’t show the total process in the Table and the final totals are the actual final totals.

If you check the total change in leakages (S + T + M) in Column (6) you see they equal $100 which matches the initial injection of government spending. The rule is that the multiplier process ends when the sum of the change in leakages matches the initial injection which started the process off.

You can also see that the initial injection of government spending ($100) stimulates an eventual rise in GDP of $179 (hence the multiplier of 1.79) and consumption has risen by 114, Saving by 29 and Imports by 36.

The total tax take is thus $36 after the multiplier process is exhausted. For those who are familiar with algebra, the total change in teax revenue is equal to 0.2*1.79*$X, which in English says equals the tax rate times the multiplied initial change in aggregate demand.

So while the overall rise in nominal income is greater than the initial injection as a result of the multiplier that income increase produces leakages which sum to that exogenous spending impulse. At that point, the income expansion ceases.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

This Post Has 0 Comments