I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

Age discrimination against our teenagers should end

I haven’t much time to write today – I’m off to Sydney later where I will be a speaker at the following event – Open Forum: Young and old-age discrimination and the economy. I will be sharing the podium was the Age Discrimination Commissioner of the Australian Human Rights Commission, a Federal government agency. The topic is how can Australian businesses and government make better use of our youth and senior citizens. As regular readers will know I regularly try to push the parlous state of the teenage labour market into the policy arena, with varying degrees of success. But today’s event is high-profile and provides a good platform for advancing these issues. This blog covers some of the issues that I will raise.

But, first, a little bit of madness to begin with …

To start with today, I thought you might like to share in my entertainment for today. My Austrian friend Stephan sent me this gem from an article in the German newspaper Handelsblatt about last weekend’s G20 summit im Mexico:

The Article was entitled Deutschland bleibt bei Schuldenhilfen vorerst hart – or Germany will remain tough for the time being on debt bailouts (more or less).

In that article which is pretty standard sort of description we read:

Die Europäer hoffen darauf, dass sich die G20-Staaten stärker an den Kosten der Schuldenkrise beteiligen. Ein Weg könnte darin bestehen, dass zahlungskräftige IWF-Mitgliedsländer wie China oder Japan dem Fonds bilateral Kredite geben, die dann als Hilfen unter anderem nach Europa fließen könnten.

TRANSLATION:

The Europeans hope, that G20 members will more strongly contribute to the cost of the debt crisis. One way could be, that wealthy solvent IMF member countries such as China or Japan will provide bilateral loans to the Fund, which could then create development aid to Europe and elsewhere.

The word “zahlungskräftig” means “an entity which is wealthy and solvent and can afford additional spending without worrying about its financial situation.

Also “Europeans hope” is code for “Germans hope”.

After you stop laughing just consider the sheer hypocracy of this “wish”.

Japan – large and continuous budget deficits, the highest public debt ratios in the world – allegedly, if you believe the logic of the likes of Rogoff and Reinhardt, the IMF, the OECD, all the right-wing “think tanks”, the majority of my profession and many others, on the brink of insolvency and default.

Japan – about to run out of money because of the ageing population and a local bond market that is allegedly about to stop investing in yen-based public debt.

Japan – on the cusp of hyperinflation because the Bank of Japan has expanded its balance sheet (monetary base) with too much “money printing”.

Japan – oh insolvent one!

And, that doesn’t even consider China. Oh China – how wealthy thou art!

The estimates of GDP per capita provided by the IMF World Economic Outlook – September 2011 – reveal the following relationships (in international dollars):

Luxembourg $84,829 (rank 2nd)

Netherlands $42,330 (rank 9)

Austria $41,805 (rank 10)

Ireland $39,507 (rank 15th)

Germany $37,935 (rank 17th)

France $35,048 (rank 23rd)

Japan $34,362 (rank 24th)

Italy $30,165 (rank 29th), and

…

…

Peoples Republic of China – $8,394 (rank 90th)

The rich are now becoming mendicants. Haven’t the Germans any pride?

Now we can move on.

Age Discrimination and the economy

Australia has made significant advances in reducing age discrimination. The federal legislation pertaining to age discrimination covers the diversity of areas including employment, education and training, finance, accommodation, and consumer affairs.

The age discrimination debate is often cast in terms of a human rights agenda. So if a worker is forced by dint of their age to prematurely exit the labour market and are thus denied the opportunity to support themselves then we say that the human rights have been violated.

I have written in the past (academic work) that an empirically based, experiential notion of human rights suggests that governments are violating the right to work by refusing to eliminate unemployment via appropriate use of budget deficits.

Persistent, demand-deficient unemployment is not compatible with fundamental human rights in that unemployment denies those affected access to income and hence participation in markets, it reduces the opportunity for advancement and stigmatises those affected, and violates basic concepts of membership and citizenship.

Without the right to work, afflicted individuals are denied citizenship rights as surely as they were denied the right of free speech or the right to vote. As long as employment is not considered to be a human right, a portion of the community will be excluded from the effective economic participation in the community

The concept of work as a human right is not new, and has spanned the ideological domain for the past 300 years. In the last century, both the United Nations and the International Labour Office have debated with the right to work question.

Employment is a basic human right was enshrined in the immediate Post World War II period by the United Nations. In 1945, the Charter of the United Nations was signed and ratified by 50 member nations. Article 55 defines full employment as a necessary condition for stability and well-being among people, while Article 56 requires that all members commit themselves to using their policy powers to ensure that full employment, among other socio-economic goals are achieved.

Employment transcends its income generating role to become a fundamental human need and right. This intent was reinforced by the United Nations in the unanimous adoption of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 23 of that treaty outlines, among other things, the essential link between full employment and the maintenance of human rights.

(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

(2) Everyone, without discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

(3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration, ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

(4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

While unemployment was seen as a waste of resources and a loss of national income which together restrained the growth of living standards, it was also constructed in terms of social and philosophical objectives pertaining to dignity, well-being and the quest for sophistication.

It was also clearly understood that the maintenance of full employment was the collective responsibility of society, expressed through the macroeconomic policy settings. Governments had to ensure that there were jobs available that were accessible to the most disadvantaged workers in the economy.

I consider the following six propositions govern a rights-agenda when it comes to the labour market:

- There should be a right to work.

- This right should be a statutory right.

- The State should bear the responsibility for implementing this right.

- Access to work should not be conditional.

- The right to work and a full employment policy are inexorably linked.

- A full employment program, encompassing the right to work, can be implemented which also guarantees price stability.

Employment is a fundamental human right

There are two broad ways to establish a right to employment:

- To assert a natural right along the lines of the doctrine of natural rights which dominated the thinkers of previous eras.

- To use factual experience and analysis of outcomes derived from these experiences. This is a pragmatic, instrumentalist approach.

The natural right approach relies on faith to motivate the conclusions – that is, some prior religious belief or precept. The calls for full employment based on various Papal Encyclicals (for example, Rerum Novarum , 1891; Laborem Exercens, 1981) and other Catholic writings fit into this approach. The content depends on the prior faith.

While the Christian Democratic ideals embodied in the All Souls concept in Catholicism provide a firm basis for solidarity or collective will in society and thus a justification for government intervention to drive unemployment to its irreducible minimum, they still require one to accept the prior belief system.

However, the conclusions can be separated from the prior beliefs and be based in the empirical, causal level of perception.

One does not have to resort to these non-empirical and extra-causal concepts to make the claim that employment should be considered a human right.

Citizenship and membership are relevant concepts. Discussion of human rights tends to concentrate on civil and political rights. However, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights does include the right to work, the right to food and the right to social security.

Both the United Nations and the International Labour Office have ratified the right to work with the 1946 ILO Declaration of Philadelphia asserting full employment as a national and international goal.

While the right to employment has been often replicated in international legal instruments, this is as far as it has gone. Countries have been reluctant or unable to mandate such a right, often within the context of their reluctance to codify and enforce any human rights for citizens.

Given these issues it has been acceptable to regard the right to work as a non core right that should be left to individual countries to enforce or to be interpreted in the context of rights of work, including EEO, non discrimination and freedom of association.

Article 6 of the ILO incorporates the right to work, but is more precisely about the right of those in employment. In most industrialised nations there is extensive legislation and common law governing employment and employment rights, including bargaining, EEO, non-discrimination, unfair dismissal, yet there is zero legislation on the right to work.

It seems that employment rights have been narrowly interpreted as encompassing the rights of those in employment and excluding any rights to those who are unemployed.

Why should work be regarded as a right?

As a starting point, labour income constitutes the major income source for the majority of individuals and households. Without income, ability to participate in a market economy is curtailed.

This exclusion has long been recognised through the provision of safety net protection for those who are unable to participate in the labour market by virtue of age, infirmity and caring responsibilities.

It was also the case for those who were without labour income by virtue of unemployment. Access to income also governs access to other rights, including minimum requirements of clothing, food and housing. Paid employment shares a direct relationship with food and water as a requisite for subsistence in many societies.

Unemployment and underemployment, together with a lack of access to fertile agricultural land, means inadequate income, misery and early death for millions across the globe.

Paid work provides the employed with choice in the market economy and the opportunity for advancement. The unemployed have limited access to credit and limited access over the range of goods and services they can purchase. They are not in a position to save for education, holidays and housing improvements. Their choices are constrained by their lack of income.

Without social transfers they have to depend upon savings, family transfers or black economy activities in order to sustain minimum living standards. Their exclusion goes beyond this. They are not accorded the status attached to employment and they make no contribution to market activity; the barometer of worth in a market economy.

What do we mean by the right to work? Those who wish to do so should be able to obtain paid full-time (or fractional) employment. This guarantee should be made by the State and it should be legally enforceable in much the same way as other rights.

Should it be any work as designated by the State? No, those exercising their right to work should be given options as to the type of employment they wish to take up.

What wage rates should they be paid? They should be paid minimum adult rates of pay and be accorded to same rights and conditions associated with full-time market employment (or pro rata) – holiday and sickness benefits, a safe workplace, protection against unfair dismissal.

For how long should they be employed? For as long as they wish while satisfying the standard conditions of employment. Those exercising this right could regard guaranteed jobs as a temporary step towards higher paid employment in the market sector.

The neglect of either national or international consideration of the right to work enables unemployment to flourish across the globe.

A right to work is the precondition for eliminating unemployment and its enormous costs and consequences. This is an imperative that is country specific. It is clear that such a right will not (beyond platitudes) be accorded the status of an internationally enforceable obligation.

However, if the right is enshrined in Australian law it will mean that governments will be legislatively forced to pay more than lip service to unemployment. It will also mean that the Federal government would be responsible for developing and implementing an effective full employment policy.

Full employment and the right to work

Full employment was regarded as a standard objective of economic policy in the post war period. In the “golden age” between 1945 and 1970 full employment was for many Capitalist and Socialistic economies regarded as a reality.

There was only disagreement over how it was defined and how it was best achieved. From the early 1970s and the first oil price shock, unemployment has edged upwards and full employment has either been either redefined or ignored. Indeed, unemployment became an important tool for reducing inflation and stabilising inflation expectations.

The right to work and full employment are inexorably linked. If there were a legislated right to work then governments would have to contemplate, as they did in the post 1945 period, how they could satisfy this right, and in the process realise full employment and eradicate unemployment. One consequence of a right to work would be a full employment economy and a full employment policy.

The implications of a full employment policy are considerable.

First, it would mean greater use of labour and capital resources, as mentioned the single most significant efficiency reform that could be implemented in Australia is the elimination of unemployment. The direct financial benefits to the economy would be enormous; as indicated, of the order of 10 per cent additional GDP every year.

Second, it would mean fewer fluctuations in aggregate economic activity. By legislation the government would be forced to generate jobs for those who are made redundant by the private sector. Such a situation would offer greater certainty for investors in the private sector since investment decisions would be undertaken in an ongoing full employment economy.

Third, the extent of exclusion, poverty and costs associated with unemployment will be significantly reduced. It would be a policy that facilitated social inclusion rather than social exclusion.

Fourth, governments would have to approach other economic goals from a full employment context, not, as currently, assume a given rate of unemployment and attempt to stabilise prices or reduce the current account deficit at this unemployment rate. Full employment would be the default setting for policy.

Fifth, employers would be forced to contemplate how to better utilise labour and how to raise labour productivity through investment in machinery, technology and training. There would no longer be the emphasis upon cost cutting, lower wages and static efficiency gains associated with surplus labour conditions.

The issue then is one of synthesising the right to work with a full employment policy. This union is possible through the introduction of a Job Guarantee

Age discrimination

Please read the following blog – The scourge of youth unemployment – where I discussed some of the issues related to teenage labour markets. While the following discussion uses Australian data, the trends are common in the advanced economies.

Much of the focus of the Australian Human Rights Commission has been on age discrimination which impacts on older people. It is clear that in past recessions, as job opportunities declined, older workers were forced out of the labour market and into early retirement.

Many of these workers found some relief by being able to access disability support pensions. But the reality was that these workers were being trashed by firms operating under the cloak of a lack of overall spending.

All sorts of reasons have been advanced in the literature to explain why firms choose to ditch older workers, who presumably have a lifetime of work experience and many productive years of service ahead of them.

The reality is that when jobs are scarce, firms use all sorts of screening mechanisms to determine who will be relegated to the jobless queue. Typically, these “screens” are based upon personal characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity – rather than any coherent evaluation of any worker’s inherent or potential productivity.

When the labour market is slack, employers can engage in what is known as “pure and simple” prejudice because the costs of such irrationality are virtually zero. It is only when the labour market is tight that engaging in such puerile behaviour becomes costly to firms.

The evidence is clear – at times of strong employment growth – the incidence of prejudicial discrimination declines because firms can no longer afford to refuse to employ productive workers based on these personal characteristics.

While the literature emphasises the personal preferences of the employer in relation to discriminatory behaviour, we can take a broader view and locate prejudicial conduct in terms of the defining characteristics of the dominant ideology in a society.

That is the approach that I take in my talk at the Open Forum today.

To be specific, the relegation of workers to the unemployment queue as a result of explicit policy decisions taken by the federal government (that is, the deliberate choice to run fiscal policy settings that reduce aggregate demand below the level necessary to achieve full employment) – is an example of discriminatory behaviour.

When this behaviour manifests in the form of disproportionate burdens being imposed on certain age cohorts, then it becomes an example age discrimination.

In that sense, it should become a matter for the Australian Human Rights Commission.

While most of the emphasis in the public debate has been on older workers, the plight of Australian teenagers is significantly more serious.

Since the crisis began (February 2008), older workers have not been excluded from the employment opportunities that have emerged. This is not to say that the labour market for older workers is free from discrimination.

Far from it, but the experience of the younger workers over the same period is in stark contrast.

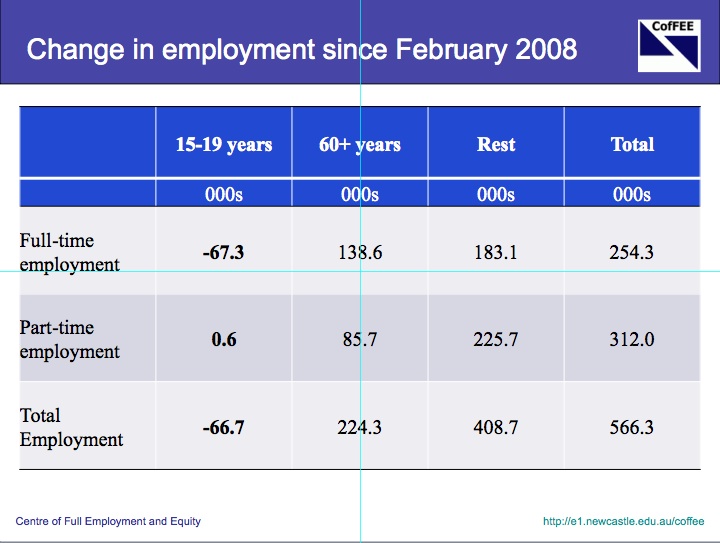

The following slide is taken from today’s talk at the Open Forum in Sydney. It shows that overall, the Australian economy has produced (net) 566 thousand jobs since February 2008. That month was the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle and signalled the beginning of the crisis.

Workers aged 60 and over have gained 224 thousand of those jobs, which is significantly greater than their labour force representation would predict. The point is that there is less evidence now of older workers being excluded from job opportunities.

In stark contrast, teenagers have lost 67 thousand jobs over the same period and all these losses have been in terms of full-time employment.

So the demand-deficiency is exacting a significant toll on a specific age cohort, which amounts to age discrimination.

By failing to take action to restore the employment opportunities to our youth, the Australian government is violating its own legislative charter to eliminate age discrimination in our country.

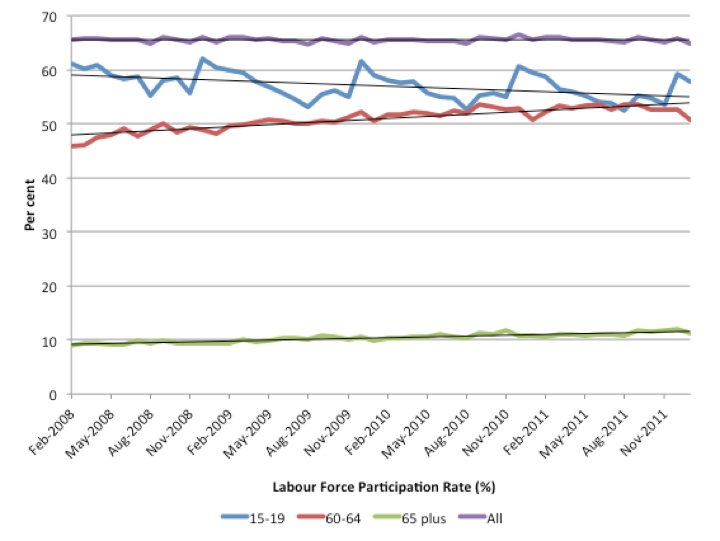

The next slide shows the labour force participation rates for older, younger workers, and all workers. The black lines are simple linear trends.

I should note that the data in this graph are the original series (that is, not seasonally adjusted) so you get the end of school seasonality in the teenage time-series (around each November – for southern hemisphere school year).

The participation rates for older workers has been rising since the crisis began. Some people have argued that this trend reflects the fact that older workers experienced major losses in wealth as a result of the financial crisis and have been forced to work longer than in the past. This question remains unresolved at present due to lack of evidence. I am doing some work on that question at present.

By contrast, the teenage participation rate has declined over the same period. So not only has the demand-side of the teenage labour market collapsed (that is, employment has been shed in large numbers), but the supply-side has also contracted.

The latter means that teenage workers have reacted to the demand-side contraction by withdrawing from the labour market – which economists refer to as the discouraged worker effect.

Discouraged workers are considered to be the hidden unemployed because for all intents and purposes they would accept a job immediately should one be offered but have ceased to actively seek employment as job opportunities shrink.

The demand-side impacts are clear – that is, we can see the job losses that teenagers have endured. But the supply impacts (that is, the reduced participation rate) are less clear and need some calculations.

The participation rate in January 2008 (the most recent peak) for teenagers was 61.4 per cent. In January 2012 if they declined to 54.8 per cent.

What does that imply about hidden unemployment for 15-19 year olds? If we consider all that participation rate decline to be the result of a discouraged worker effect (which will not be far off the mark given there has been no major changes in education policy in the meantime – that is, to change behaviour with respect to participation in full-time education), then the 15-19 year old labour force would be around 916 thousand in January 2012 rather than 817 thousand which was officially recorded.

The decline in the participation rate translates into 98.3 thousand teenagers having left the labour force since the crises began (in February 2008) as their employment prospects vanished. That figure has to be added to any hidden unemployment that was present at the peak of the cycle.

In January 2012, the official teenage unemployment rate was 16.3 per cent. Further, the official underemployment rate

If you add the 98 thousand back into the official unemployed then the 15-19 unemployment rate rises to 25.3 per cent rather than the 13.5 per cent recorded as the official unemployment rate by the ABS.

Add that to the underemployment rate (around 13.5 per cent – noting that the ABS only publish this for 15-24 year olds so we are approximating) – and you get a broad labour force underutilisation rate for teenagers of around 38.8 per cent in January 2012.

As I have noted in the past – this deliberate wastage of our teenagers is up there with the worst nations in the world – developed or otherwise.

What about the claim that teenagers are really combining labour market experience-seeking with full-time education and we shouldn’t be concerned?

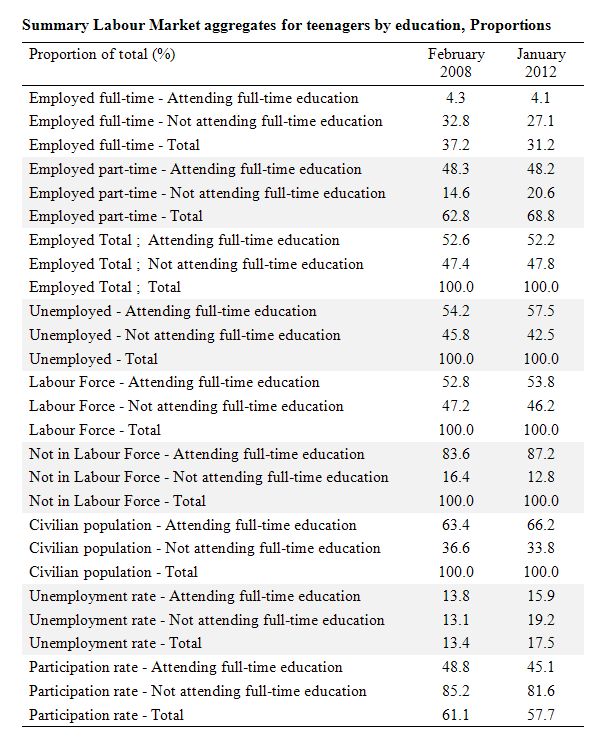

The following Table shows the proportions of teenagers in each labour force category by educational status. February 2008 was the low-point national unemployment rate in the last cycle and from there the impacts of the financial crisis began to manifest.

A notable feature is the reduction in full-time work and the rise in part-time work as a proportion of total employment for those not attending full-time education. Further, it is interesting that a majority of employed teenagers are attending full-time education.

The declining opportunities for those not attending full-time education is the worry. You can see that manifesting in terms of the unemployment rate increase for this cohort (from 13.1 per cent at the start of the crisis to 19.1 per cent now).

As we explored earlier, the official unemployment rate also disguises the true extent of the joblessness, given that the participation rate for teenagers has fallen so sharply over the period since February 2008.

The decline in participation is larger for those not attending full-time education which raises the question of what they are actually engaged in.

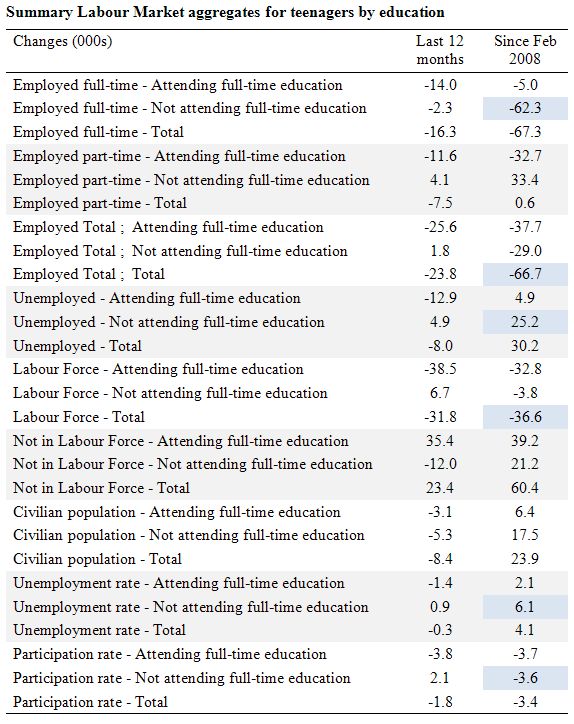

This Table shows the changes in thousands in the labour market aggregates for teenagers over the last 12 months (January 2011-2012) and since the crisis began (February 2008). There you start to see the sorry story in clearer terms. I also highlighted some of the cells to make it easier to see the significant trends.

As we noted above, teenagers have lost a huge number of jobs over the period since the crisis began (February 2008) and the vast majority of those job losses have been in terms of full-time employment.

This Table shows that those losses are concentrated among teenagers who are not attending full-time education. The data also shows that the vast majority of the rise in unemployment since February 2008 has been born by the same cohort. The change in the unemployment rate reflects this demise in demand for teenagers who are not attending full-time education.

Moreover, the rise in the unemployment rate, bad enough as it is, underestimates the true decline in labour market opportunities for this cohort. You can see that the participation rate has also plummeted.

This data is original whereas the data used earlier to compute broad labour underutilisation rates for teenagers is seasonally adjusted. That explains why some of the aggregates (such as, participation rates) vary.

Why does this all matter and what should be done?

In last week’s blog – Fiscal austerity undermines the future as well as the present – I outlined the challenge facing nations with rising dependency ratios.

The challenge relates to the capacity of the economy to produce new goods and services and to generate employment and productivity growth, for example. They are distinct from, say, financial issues, which relate to capacity to pay.

A government that issues its own currency clearly always has the capacity to pay – in the sense that it can always buy whatever is for sale in the currency that it issues. There is no sense in which a currency-issuing government can ever “run out of money”.

But there is a possibility – one that can be avoided, or at least attenuated through sound economic policy – that an economy will fail to produce sufficient real goods and services commensurate with the expectations (concerning the standard of living) of the population.

It is in this respect that rising dependency ratio presents a challenge that must be met by government.

The question of aged discrimination is central to this challenge.

I won’t repeat the macroeocomic arguments in that previous blog. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) clearly demonstrates that governments should always be forward looking and accept that its fiscal position will reflect changing challenges in terms of providing adequate public services and infrastructure while always be seeking to ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain production at the levels required to fully employ the available workforce.

In terms of the challenges presented by rising dependency ratio, the obsession with budget surpluses that the current policy debate encourages will actually undermine the future productivity and future provision of real goods and services.

The quality of the future workforce will be a major influence on whether our real standard of living (in material terms) can continue to grow in the face of rising dependency ratios.

Governments should be doing everything that is possible to educate, train and employ our youth so that they will achieve higher levels of productivty into the future and offset the inevitable rises in the dependency ratio.

This requires:

1. That there is significant investment in education – governments should not try to “save” money (as part of some mis-guided fiscal consolidation program) by cutting expenditure to public schools.

2. There should be ways to ensure the youth are either in education or work.

By pursuing a budget surplus when there is clearly significant excess productive capacity in Australia and when the private domestic sector is highly indebted the government is not only damaging the present but also undermining the future.

This manifests as age discrimination against our youth in particular.

Maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is madness to exclude our youth – many of whom will enter adult life having never worked and having never gained any productive skills or experience.

Those that exit our formal schooling system are also increasingly falling behind.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

Ultimately the ageing society challenge is about about political choices rather than government finances. If there are goods and services produced in the future, then the sovereign government will be able to purchase them and provide them to the areas of need in the non-government sector.

The challenge is to make sure these real goods and services will be available.

The first thing a forward-looking government should do is to introduce a Youth Guarantee – which would ensure that no teenager is without work should they decide to participate in the labour force.

At the other end of the age spectrum, the concern is clear – older workers who are forced to exit the labour market prematurely are not able to bring their considerable experience to bear on developing high productivity workplaces.

The Youth Guarantee should embrace both ends of the age spectrum – the older workers bring their experience to develop skills for the teenagers who cannot find work elsewhere and do not wish to participate in full-time education.

This should be a policy priority.

Conclusion

I have run out of time and have to go to Sydney.

That is enough for today!

“What wage rates should they be paid? They should be paid minimum adult rates of pay and be accorded to same rights and conditions associated with full-time market employment (or pro rata) – holiday and sickness benefits, a safe workplace, protection against unfair dismissal.”

Low-skilled and unskilled adult workers and unions would love to see teenage min. wages pushed higher as it would reduce competition and increase teenage unemployment by removing the penalty employers incur when they exercise their prejudices against teenagers (and women). If this policy took place without an enormous spending program to accommodate the new labour force entrants that it would attract, it would likely hurt the very people it sought to assist.

@Esp Ghia,

You cannot force the private sector to hire people if there is not enough demand for their goods and services to warrant such hiring. However the government should hire anybody wanting to exercise their human right to work. This is the Job Guarantee for everybody able and willing to work.

The Job Guarantee kick starts a virtuous circle, by providing higher income to the JG workers, increasing aggregate demand (people spend what they earn). This in turn allows the private sector to expand (in order to fullfil the ioncreased demand) and hire more people. Of course this means the private sector has to offer working conditions and wages at least as good as what is provided by the JG. The JG programme should never try to retain workers, it should never compete for labour with the private sector. The JG conditions basically provides minimum wage and least acceptable working conditions without even the need to enforce them by law, because people can always go back to the JG if the private sector is abusing them. The JG is the anchor to the whole economy.

So yes government spending is likely to go up, because it would need to pay JG wages. This is not a problem as Australia is sovereign in its own fiat currency, and therefore is not financially constrained. One could also argue that, as a result of such a policy, tax revenues will increase.

All this has been explained many many times by Bill, if you lookup Job Guarantee on this blog you will have it all in details.

So is this an application of Say’s Law?

This is exactly the cohort that is described as radicalizing in Saudi-Arabia and quite a few others of the Middle Eastern/North African countries, correct? And the group that is most likely to drift into crime to augment their income, in the US, for instance.

So in addition to concerns about future productivity there are very tangible short-term benefits to addressing this issue, I’d assume.

With respect to EZ hypocrisy – amazing isn’t it?!! They don’t realize the sheer stupidity of that which they do. Their erstwhile “superior” currency framework – so deemed because it steers clear of nonsense neo-liberal (investor confidence) ideas of devaluation risk – has to depend on support from a deficit burdened, debt-to-GDP aberration like Japan. Seriously… if Japan were in the EZ, they’d be getting ready to sell Mt. Fuji to the banks right about now. In.Credible.