I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal austerity undermines the future as well as the present

Amidst all the political turmoil in the Australian government this week, there was a highly significant report issued by the government (finalised December 2011 but released by the Government on February 20, 2012) – Review of Funding for Schooling – which showed not only how unequal our education system is but also how far behind we have fallen relative to other nations (particularly those that are more important trading partners). For a government which pretends to be concerned with equity and efficiency the Report posed huge challenges. Not only did it suggest current policy was failing, the Report estimated that over AU$5 billion should be invested in education reform to not only improve standards but also ensure that the massive inequalities between rich and poor with respect to educational access and outcomes are reduced. The response by the Australian government was that its priority remained the achievement of a budget surplus in 2012. Here is a classic demonstration of how a failure by the Government to understand the characteristics of the monetary system that it runs leads to poor outcomes in the short-run, but also undermines the future prosperity of the nation.

Here is a real problem that is shared by many advanced nations – rising dependency ratios.

Now before you jump up and say: (a) this is what treasuries around the world are saying too; and (b) doesn’t Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) demonstrate that the logic used by these treasuries and other bodies in relation to fiscal burdens of the ageing society are false – take stock and consider what the nature of this “real” problem actually is.

I use real in the economic sense – that is, real as opposed to nominal.

Real problems relate to the capacity of the economy to produce new goods and services and to generate employment and productivity growth, for example. They are distinct from, say, financial issues, which relate to capacity to pay.

A government that issues its own currency clearly always has the capacity to pay – in the sense that it can always buy whatever is for sale in the currency that it issues. There is no sense in which a currency-issuing government can ever “run out of money”.

But there is a possibility – one that can be avoided, or at least attenuated through sound economic policy – that an economy will fail to produce sufficient real goods and services commensurate with the expectations (concerning the standard of living) of the population.

It is in this respect that rising dependency ratio presents a challenge that must be met by government.

While the following brief empirical analysis relates to Australian population trends, the experience is common in many advanced countries. In some countries, the dependency ratios are rising more alarmingly than in Australia.

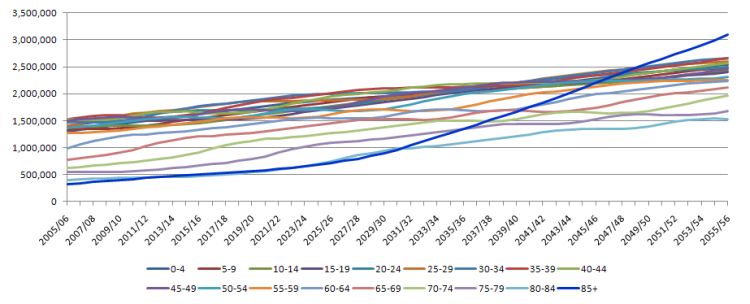

To give you some idea of the demographic shifts that are projected to this occur in Australia the following graphs are based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics Series A or High Population growth model. It assumes that the total fertility rate will reach 2.0 babies per woman by 2021 and then remain constant, life expectancy at birth will continue to increase until 2056 (reaching 93.9 years for males and 96.1 years for females), Net overseas migration will reach 220,000 by 2011 and then remain constant, and large interstate migration flows. So worst case scenario and probably overly optimistic.

The following graph shows the population projections for five-year age cohorts (0-4, 5-9 and so on) until 2055/56. All the lower lines currently are the older cohorts and over the period shown they become more dominant especially the 85+ (blue line with the rapid upward slope around 2030).

At present the 84+ cohort comprises 2 per cent of the total Australian population. By 2056/56 this proportion is expected to rise to 7.3 per cent. Similar increases are expected in the successive younger (but older) cohorts.

I wrote about dependency ratios in detail in these blogs – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time and The myths of the ageing society debate.

By way of summary, the standard dependency ratio is normally defined as 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years). Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old.

To take into account how many workers are actually productively employed, policy makers use the so-called effective dependency ratio which is the ratio of economically active workers to inactive persons, where activity is defined in relation to paid work (thus ignoring major productive activity like housework and child-rearing).

The effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age (15-64 or whatever) are actually producing. There are many people in this age group who are also “dependent”. For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and early retirees fit this description.

However, the unemployed and underemployed are usually excluded because the statistician counts them as being economically active. In a period of rising underemployment and persistent unemployment you can imagine that their inclusion provides a very different picture of the dependency ratios.

The other angle is that if our youth are being excluded from paid work now their future productivity is being seriously compromised. There is ample evidence to show that people who do not engage with paid work early typically have low-wage, unstable work histories.

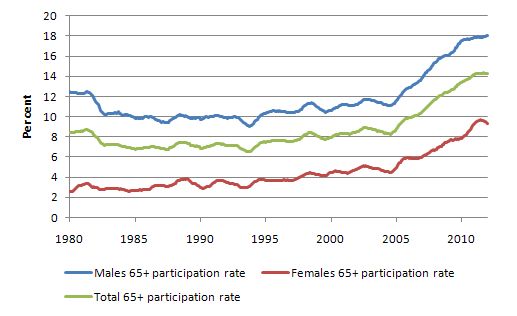

The first graph provides some information about this issue because it shows the labour force participation rate of those who are above 65 years of age (a 12-month moving average to disclose trends) for males, females and all persons. It has clearly been rising since 2003 and is now over 14 per cent. It will be expected to rise further in the coming decade as this cohort seek ways to attenuate the wealth losses that the GFC has wrought on their retirement funds.

It is highly likely that more than 25 per cent of this group will remain active in the labour force by 2050, especially given the rises mooted in the pension age.

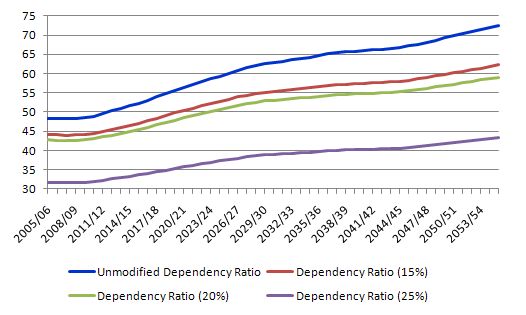

The next graph shows three real dependency ratios I computed based on a status quo (say 15 per cent participation by over-65s), and participation rates of 20 per cent and 25 per cent averaged over the period between now and 2055.

The blue line at the top is the unmodified dependency ratio which is projected to reach 73 per cent by 2055/56. The real dependency ratios below it assume increasing participation by the over-65s. If the highest participation is accurate then the dependency ratio would be 43.3 per cent by 2055/56 rather than the 62.2 per cent if the participation rate of the 65+ cohort remains as it is now.

The reason that mainstream economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions of the government budget constraint as explained above.

For them, a rising dependency ratio suggests that there will be a reduced tax base and hence an increasing fiscal crisis given that public spending is alleged to rise as the ratio rises as well.

The mainstream approach to the higher dependency ratios is to increase the retirement age (because people live longer they should work longer); redistribute population via migration from younger to older countries; and/or reduce the real value of public entitlements and force increasing numbers to provide retirement income privately.

Further, the neo-liberals claim that governments have to run budget surpluses now to “save” up the funds that will reduce the alleged budget trauma in the future as increasing numbers of people draw on public funds for health care and pension support.

However, all of these remedies miss the overall point.

The ageing population does not present a financial crisis for government. The challenge that governments will have to face is a real one, which has two main dimensions:

1. Will there be enough real resources available to the nation to provide the required goods and services?

2. Will those resources be transformed into the goods and services at sufficient levels of productivity to meet the rising demands of the unproductive component of the population given that the productive component is shrinking?

These are the challenges of the ageing society and rising dependency ratios?

If we believe a crisis is coming, then are we really saying that there will not be enough real resources available to provide, say, aged-care at an increasing level? In all the mainstream literature, you never will see the problem posed in that way.

The neo-liberal worry always claims that public outlays will rise because more real resources will be required “in the public sector” than previously and that eventually the rising deficits will bankrupt the government.

MMT teaches us that a currency-issuing government cannot become bankrupt in financial terms unless the government, for some strange political reason, decides to default on its outstanding obligations. For nations such as Australia, the US, the UK etc that has never happened. So in financial terms, there is no solvency risk

There will be no problem with our ageing societies if there are enough real resources are available to meet the future demands. This puts the need to develop better ways of interacting with our natural environment squarely in the centre of the frame of policy priorities. If we poison the world then we will poison ourselves.

While MMT doesn’t say anything about environmental sustainability per se, what it helps us understand is that the government has the financial resources to promote green technologies and better land-use etc. These policy areas also provide fertile ground for Job Guarantee-type positions – at least at the lower skill levels.

Further, the second dimension of the overall ageing society challenge directly bears on the educational and training debate. Which takes me back to the introduction.

The Gonski Review

The 300-odd page Review of Funding for Schooling was the first serious study of Australian educational funding since 1973.

Since then a series of ad hoc changes have been made – mostly at the expense of the public schooling system. Successive governments have ploughed increasing quantities of public funding into the private school system and then towards to elite of that cohort. The evidence is that the private school system caters for the rich and high-income families, whereas the vast majority of students are “educated” in the public school system.

For those who are interested in the crazy system of educational funding in Australia this 2007 Report – Australia’s School Funding System (aka the Gonski Review) – provides a good introduction (although policy changes since have occurred). The current situation remains similar to that outlined in this paper though.

The Canberra Times article (February 21, 2012) – Gillard’s dissembling response undoes much of Gonski’s backbreaking work – described the funding model as:

… a tangled web of financial intrigue involving ancient deals negotiated between the Commonwealth, states and territories and underpinned by a dizzying array of financial incentives, anomalies, bribes, threats and add-ons that attach themselves during the political cycle.

I would add that the funding model has been infested with the growing dominance of neo-liberalism over the last three decades which has seen the funding skewed to the richer schools catering for the children of privilege. Further, the poorer schools where the disadvantaged families have to attend have fallen well behind.

The essential findings of the Review are clear:

1. “Over the last decade the performance of Australian students has declined at all levels of achievement, notably at the top end. In 2000, only one country outperformed Australia in reading and scientific literacy and only two outperformed Australia in mathematical literacy. By 2009, six countries outperformed Australia in reading and scientific literacy and 12 outperformed Australia in mathematical literacy.”.

2, “Australia has a significant gap between its highest and lowest performing students. This performance gap is far greater in Australia than in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, particularly those with high-performing schooling systems. A concerning proportion of Australia’s lowest performing students are not meeting minimum standards of achievement. There is also an unacceptable link between low levels of achievement and educational disadvantage, particularly among students from low socioeconomic and Indigenous backgrounds.”

3. “Funding for schooling must not be seen simply as a financial matter. Rather, it is about investing to strengthen and secure Australia’s future. Investment and high expectations must go hand in hand. Every school must be appropriately resourced to support every child and every teacher must expect the most from every child.”

4. There should be a minimum public spend per enrolled student – the so-called “schooling resource standard” which would then be increased for children from disadvantaged or indigenous backgrounds. Students with a disability should also be given a loading on the mimumum. Note that Gonski failed to address the issue of whether public funds should fund private schools per se, a point I will write about in more detail in another blog. I am against state aid for private education.

5. A $5 billion investment boost is needed to begin redressing these problems (in 2009 dollars).

ABC Economics correspondent, Stephen Long provided the best commentary on the underlying message that you can glean from reading the Gonski Review document (February 22, 2012) – Gonski, plutocracy and public policy.

Stephen Long notes that the data in the Review shows that:

… the wealthier “independent” schools … are bastions of privilege, while government schools are a repository for the disadvantaged.

Further, the private schools lobby always claims that the system caters for the disadvantaged and poor (through special access arrangements etc). Stephen Long says that the Gonski Review “smashes” this myth:

On the contrary, close to half of all students in these schools come from families in the top quarter of the population for “socio-educational advantage”: that is, their parents have relatively high-paid, high-skilled jobs and high levels of educational attainment. That’s more than double the share in the government school sector. About three quarters of all students in the “independent” schools come from families in the top half of the population for socio-educational advantage. Just 13 per cent come from families from the bottom quarter.

It is clear from the data that the private schools take their students from “families at the top of the pile for income and education”. Privilege reinforcing privilege.

The vast majority of Australian children (over 75 per cent) are educated within the public school system yet it has been starved for funds by successive governments seeking to not only cut back on government deficits but also to pander to the neo-liberal sentiments.

An overwhelming majority (around 80 per cent) of students from “relatively poor, ill-educated households” are educated within the public system. The same sort of proportions apply when we consider disabled students, indigenous (with the categories often overlapping).

But the Gonski Review shows that the public schools get less funding per student than the private schools, and this disparity widens dramatically when it comes to the elite private schools.

So the simple conclusion: the majority of our public schools are underfunded and the educational standards are going backwards. We are falling behind nations such as China and India, significant trading partners and it won’t be long before our standards of living fall as a result of the failure to invest in public education.

Government’s Response

Timed with the public release was the The Gillard Government’s Response to the Review Report. Given they received the Report in December and took at least 2 months to come up with their response, one might have expected more than was produced.

First, the Government had stacked the Terms of Reference for the Review from the start by imposing the politically-motivated constraint that no school would lose any funding as a result of the outcomes of the Review.

So there could be no challenge to the outrageous system of funding that pumps millions of public dollars into the most elite schools in Australia and starves the public schools.

Second, the Gonski Review had identified “a need for an expanded stream of Australian Government capital funding” for Australian Schools.

The Government’s Initial Response rejected this:

In some areas, the Australian Government believes that the scope of proposed new funding contributions may be too large. For example, on capital spending, the Australian Government has recently completed the largest ever program of capital investment in Australian schools … we do not envisage the significant expansion of the Commonwealth’s capital funding role.

Third, the responsible minister (Peter Garrett – former lead singer in the Midnight Oil) told the press on Monday morning that the Government’s priority was to achieve a budget surplus.

In the Government’s Initial Response we read:

The Australian Government is committed to returning the budget to surplus in 2012-13 and to ongoing fiscal responsibility. State and Territory Governments also face fiscal challenges, as do parents who do not wish to see school fees rise beyond their reach.

To take that next step requires that all of the stakeholders in education-states and territories, schools and school systems, teachers and parents- engage in constructive and productive dialogue.

In other words, the obsession with achieving the budget surplus will demand that the Government fail to address the serious issues in the Gonksi Review. All of us will suffer as a consequence.

Even the mainstream commentary is now starting to see through their obsession. The Sydney Morning Herald article (February 22, 2012) – – said:

On top of this is the government’s budget surplus fetish which has no rational economic basis in the current situation but is designed simply to pander to Abbott’s political exploitation of public economic illiteracy.

It points out that the $A5 billion estimated by the Gonski Report necessary to improve Australian education “is about 1.3 per cent of the Australian government’s budget and could be readily funded from eliminating or modifying some tax anomalies”,

More to the point, it could be readily funded by the government simply spending the currency into use. At present the budget deficit is far too low given that 12.5 per cent (at least) of our overall available workforce is idle.

The point of all of this

The ageing society (with pension and health care implications) is the most often used justification for their pursuit of budget surpluses.

The claim is that failure ot act now with respect to fiscal consolidation will result in unsustainable fiscal consequences and, even, according to the more extreme versions of the story – the government running out of money.

It is clear that governments should always be forward looking and accept that its fiscal position will reflect changing challenges in terms of providing adequate public services and infrastructure while always be seeking to ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain production at the levels required to fully employ the available workforce.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, national government finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a “scorekeeping” role.

MMT tells us that when a government boasts that a $x billion surplus, it is tantamount to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings recorded a decline of $x billion over the same period.

So when a government aims to achieve a surplus it must also be wanting the non-government $A financial asset savings to decline by an equal amount.

For nations that run current account deficits over the same period, we can then interpret that aim as saying that it is fiscally responsible to drive the private domestic sector (as a whole) into further indebtedness. That is a consequence of such behaviour. It is not what MMT would suggest is responsible fiscal management.

It follows that the entire logic underpinning the “ageing society-fiscal consolidation” debate is flawed. Financial commentators often suggest that budget surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy. This has overtones of the regular US debate in relation to their Social Security Trust Fund.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly “stored away” will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the neo-liberal misconception.

While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, it is clear that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

The standard government intertemporal budget constraint analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is ridiculous. The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner. Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures. Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain. Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When modern monetary theorists argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit. We are not advocating unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that the economy achieves full employment. Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light. The emphasis on forward planning that has been at the heart of the ageing population debate is sound. We do need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run budget surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

In terms of the challenges presented by rising dependency ratio, the obsession with budget surpluses will actually undermine the future productivity and future provision of real goods and services.

The quality of the future workforce will be a major influence on whether our real standard of living (in material terms) can continue to grow in the face of rising dependency ratios.

Governments should be doing everything that is possible to educate, train and employ our youth so that they will achieve higher levels of productivty into the future and offset the inevitable rises in the dependency ratio.

This requires:

1. That there is significant investment in education – the Gonski Review demonstrates that the Australian system is failing.

2. There should be ways to ensure the youth are either in education or work.

In this blog – The scourge of youth unemployment – I show how one can estimate the broad labour force underutilisation rate for Australian teenagers to be around 38 per cent (14.5 per cent unemployed; 13.5 per cent underemployed; and 8 per cent hidden unemployed).

So on both counts the Australian government is failing to meet the essential challenge.

By pursuing a budget surplus when there is clearly significant excess productive capacity in Australia and when the private domestic sector is highly indebted the government is not only damaging the present but also undermining the future.

Maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is madness to exclude our youth – many of whom will enter adult life having never worked and having never gained any productive skills or experience.

Those that exit our formal schooling system are also increasingly falling behind.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

Ultimately the ageing society challenge is about about political choices rather than government finances. If there are goods and services produced in the future, then the sovereign government will be able to purchase them and provide them to the areas of need in the non-government sector.

The challenge is to make sure these real goods and services will be available.

Conclusion

The idea that it is necessary for a sovereign government to stockpile financial resources to ensure it can provide services required for an ageing population in the years to come has no application.

It is not only invalid to construct the problem as one being the subject of a financial constraint but even if such a stockpile was successfully stored away in a vault somewhere there would be still no guarantee that there would be available real resources in the future.

The best thing to do now is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment and ensuring our public schooling system is well-resourced and producing first-class outcomes by rising World standards.

This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being practised.

The irony is that the pursuit of budget austerity leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

That is enough for today!

It always amazes me that those who benefited from ‘free’ eduction all the way through to university are the ones denying it to future generations.

Lack of insight and an addiction to the conventional “wisdom” seem to be the hallmarks of the current political scene but has it ever been any different?

Johnno,free university education was a policy introduced by the short lived Whitlam government. I am not familiar with the actual time line but I think that it didn’t last long into the conservative reign of Fraser and certainly not far into the equally conservative Hawke/Keating era.

Further to Bill’s post

From the ‘mouths’ of the Finns!!!!!!! …. (ABC Lateline last night)

A must ‘see’ – if missed. (And excellent questions from Emma A (and/or ABC staff) )

http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2012/s3441913.htm

(Mmm and they are “Top of OECD Pops” !!!!!!!!!!) Talk about …. “Learning Lessons!” (NT Gov Commissioned Report on Indigenous Education.

(ps and watch/re-watch this oldie but goodie from Prof Ken Robinson: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U)

So the MMT use of the word REAL refers to REAL RESOURCES as opposed to standard economic jargon where REAL refers to the purchasing ability of the unit of account less inflation?

Real = ‘sweat and atoms’ mostly.

But as ever with economics it depends on the analysis being undertaken. It’s always advisable to confirm terms when debating economic ideas. It seems to be a world that would confuse Humpty Dumpty.