I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The scourge of youth unemployment

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) released their updated this week (October 19, 2011) – Global Employment Trends for Youth: 2011 Update – which reminds us of how long the current policy failures will continue to generate negative consequences. That is, the world will be enduring the costs of the policy failures for decades to come by denying our youth the opportunity to fully participate in the economy. The increasing incapacity of our economies to provide sufficient work in hours and quality to meet the requirements of our youth is one of the major characteristics of the neo-liberal era. It is a deliberate, policy-induced outcome – that is, governments are squarely to blame for the malaise. At a time when neo-liberals use rising dependency ratios to justify their attacks on budget deficits but then fail to realise that our unemployed youth are a major casualty of the fiscal austerity – that is, our future workforce. The scourge of youth unemployment is condemning our future workers to a low-wage, unstable and productive employment history.

The ILO findings

The Global Employment Trends for Youth: 2011 update augments the “special edition of the Global Employment Trends for Youth, August 2010 on the impact of the economic crisis” published by the ILO.

The earlier Report demonstrated that “crisis led to a substantial increase in youth unemployment rates” and “at the peak of the crisis period in 2009, the global youth un- employment rate saw its largest annual increase on record”.

Youth have been more disadvantaged by the crisis than adults – “the “first out” and “last in” during times of economic recession”.

The more recent analysis presented in this update show that the “youth unemployment rate remained unchanged … in 2009 and 2010” despite some signs of growth emerging.

The ILO say that:

The specter of youth unemployment has continued to worsen in the Developed Economies & European Union, where young people paid the highest price over the course of the crisis. Youth unemployment numbers and rates were higher in 2010 than any time since measurement began in 1991. Not only did the region show the largest jump, by far, in youth unemployment rates between 2008 and 2010 … but it is also one of only three regions where the youth unemployment rate continued to creep up over the period 2009-10 …

In most developed economies, the long-term unemployment rates of youth surpassed those of adults, by far.

There has been a clear increase in inactivity among youth in the crisis years. Globally, the youth labour force participation rate decreased … with the largest regional decreases in the Developed Economies & European Union and South Asia … growing frustration over unemployment and underemployment has pushed a large cohort of discouraged youth to drop out of the labour market altogether.

So little or no jobs growth, further entrenched unemployment – with some teenagers in chronic long-term unemployment and falling participation. The lesson from the ILO is that this is a global trend.

The fall in participation is particularly worrying as I explain later using Australia as a case. The ILO note that with declining participation during the crisis (they explicitly talk about Ireland her):

… there is a massive gap now between the current youth labour force count and the expected youth labour force based on pre-crisis trends. This means many young people are either “hiding out” in the education system rather than face the job search or are idly waiting at home for prospects to improve before taking up an active job search. Had these youth been instead looking for work, the “actual” youth unemployment rate in Ireland could be as much as 19.3 percentage points higher than the official rate.

The official rate in Ireland was 27.5 per cent (2010). The same point can be made for most nations. Our leaders are ignoring massive idleness among our youth.

The ILO also note that the quality of work that the youth have been able to scrounge during the crisis “is less than ideal”. Underemployment and low-skill employment is rising.

The problem is also chronic in developing economies where according to the ILO:

… some young men and women have very little chance of ever finding work …

The ILO conjects that there will be “continuing uncertainty for young men and women and growing discontent” (which has already manifested in the Middle East in the Northern spring and among the “Los indignados” in Spain, and other protests in Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom to name a few examples).

The ILO reports that in Ireland, the rate of out-migration among people under 25 has doubled since the 2004.

The other aspect of labour market exclusion that is often ignored by the bean counters is that there are:

Increased crime rates in the some countries, increased drug use, moving back home with the parents, depression – all of these are common consequences for a generation of youth that, at best, has become disheartened about the future, and, at worst, has become angry and violent.

Hardly the ideal preparation for our future workforce and community leaders.

The ILO claim that “governments struggle to find innovative solutions to ease the jobs crisis” although according to them “Governments are not closing their eyes to the dangers”.

If you read the list of so-called government solutions to stimulating jobs growth that the ILO claims are being pursued you get the picture. Very little jobs growth potential – more neo-liberal supply-side ineffectiveness.

For example,

1. More training (Bill notes: which is ineffective if it is outside the paid-work environment).

2. More information about jobs (Bill notes: it is hard to provide information about jobs that are not there!).

3. Addressing poor signalling (Bill notes: making the CV look better for jobs that are not there!).

4. Addressing slow job growth barriers: programmes that aim to boost job creation, especial- ly for young people; public works programmes and tax cut incentives for business that hire long-term unemployed are examples (Bill notes: so where are the jobs? In Australia, as I note later, youth employment has gone backwards since the crisis. Further – why rely on the private sector which clearly will not provide enough jobs. Why not direct job creation – of a scale sufficient to solve the problem.

5. Financial and macroeconomic policies. The ILO finally have to admit that “ultimately, job growth will not come from labour market policies alone” which should say that jobs growth does not come from supply-side policies at all – it comes from stimulating demand. The ILO claim that governments have to “accelerating the repair of the financial sector balance sheets, including bank restructuring” but do not mention once the need for increasing budget deficits to directly create jobs.

Pathetic.

Ageing society issues

The youth unemployment issue is intrinsically related to the ageing society debate although you wouldn’t know that from what the politicians talk about and the policies they implement.

The attacks on the deficit are more likely these days to be based on so-called medium- to long-term challenges – given that the last four years or so have shown that the predictions that interest rates and hyperinflation would materialise with rising deficits within a few years have been shown to be erroneous.

This is the basis of the IMF’s narrative about short-term support for growth and medium-term fiscal consolidation. The ageing society (with pension and health care implications) is the mostly often used justification for their pursuit of budget surpluses.

The claim is that failure ot act now with respect to fiscal consolidation will result in unsustainable fiscal consequences and, even, according to the more extreme versions of the story – the government running out of money.

It is clear that governments should always be forward looking and accept that its fiscal position will reflect changing challenges in terms of providing adequate public services and infrastructure while always be seeking to ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain production at the levels required to fully employ the available workforce.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, national government finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a “scorekeeping” role.

MMT tells us that when a government boasts that a $x billion surplus, it is tantamount to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings recorded a decline of $x billion over the same period.

So when a government aims to achieve a surplus it must also be wanting the non-government $A financial asset savings to decline by an equal amount.

For nations that run current account deficits over the same period, we can then interpret that aim as saying that it is fiscally responsible to drive the private domestic sector (as a whole) into further indebtedness. That is a consequence of such behaviour. It is not what MMT would suggest is responsible fiscal management.

It follows that the entire logic underpinning the “ageing society-fiscal consolidation” debate is flawed. Financial commentators often suggest that budget surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy. This has overtones of the regular US debate in relation to their Social Security Trust Fund.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly “stored away” will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the neo-liberal misconception. While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, it is clear that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

A sovereign government in a fiat monetary system is not financially constrained.

The concept of the taxpayer funding government spending is misleading. Taxes are paid by debiting accounts of the member commercial banks accounts whereas spending occurs by crediting the same. The notion that “debited funds” have some further use is not applicable.

When taxes are levied the revenue does not go anywhere. The flow of funds is accounted for, but accounting for a surplus that is merely a discretionary net contraction of private liquidity by government does not change the capacity of government to inject future liquidity at any time it chooses.

The standard government intertemporal budget constraint analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is ridiculous. The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner. Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures. Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain. Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When modern monetary theorists argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit. We are not advocating unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that the economy achieves full employment. Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light. The emphasis on forward planning that has been at the heart of the ageing population debate is sound. We do need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run budget surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

The real policy issue relating to the ageing society is the movement in the dependency ratio. Please read my blog – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time – for more discussion on the dependency ratio.

The standard dependency ratio is normally defined as 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years). Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old.

To take into account how many workers are actually productively employed, policy makers use the so-called effective dependency ratio which is the ratio of economically active workers to inactive persons, where activity is defined in relation to paid work (thus ignoring major productive activity like housework and child-rearing).

The effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age (15-64 or whatever) are actually producing. There are many people in this age group who are also “dependent”. For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and early retirees fit this description.

However, the unemployed and underemployed are usually excluded because the statistician counts them as being economically active. In a period of rising underemployment and persistent unemployment you can imagine that their inclusion provides a very different picture of the dependency ratios.

The other angle is that if our youth are being excluded from paid work now their future productivity is being seriously compromised. There is ample evidence to show that people who do not engage with paid work early typically have low-wage, unstable work histories.

The reason that mainstream economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions of the government budget constraint as explained above.

For them, a rising dependency ratio suggests that there will be a reduced tax base and hence an increasing fiscal crisis given that public spending is alleged to rise as the ratio rises as well.

However, this entire discussion misses the actual importance of dependency ratios. It is not a financial crisis that beckons but a real one. What we should be concerned about is whether there will be real resources available to provide aged-care at an increasing level?

That is never question that the neo-liberals ask.

There will be no problem with our ageing societies if there are enough real resources are available to meet the future demands. In this context, the type of policy strategy that is being driven by these myths will probably undermine the future productivity and provision of real goods and services in the future.

The quality of the future workforce will be a major influence on whether our real standard of living (in material terms) can continue to grow and we take into account the rising dependency ratios.

We should be doing everything that is possible to educate, train and employ our youth so that they will achieve higher levels of productivty into the future and offset the rising dependency ratio.

Unfortunately, tackling the problems of the distant future in terms of current “monetary” considerations which have led to the conclusion that fiscal austerity is needed today to prepare us for the future will actually undermine our future.

Maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is madness to exclude our youth – many of whom will enter adult life having never worked and having never gained any productive skills or experience.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

Ultimately the ageing society challenge is about about political choices rather than government finances. If there are goods and services produced in the future, then the sovereign government will be able to purchase them and provide them to the areas of need in the non-government sector.

The challenge is to make sure these real goods and services will be available.

What does the ILO propose governments should do about this crisis?

Their proposals are often so general that they have no operational content. They read like G-20 Communiques – motherhood statements.

For example:

Develop an integrated strategy for growth and job creation to ensure long-term, sustained and concerted action for the promotion of decent work for young people. Assigning priority to youth employment requires a coherent policy framework, with measurable targets and achievable outcomes, that addresses youth employment in national development strategies and employment policies.

Which I would write – the Government commits to zero waste of our youth and will guarantee to support everyone in public education, skills training and if either of those prove unsuitable then a guaranteed job in the public sector with in-built opportunities to access career ladders.

The ILO second proposal:

Establish broad-based partnerships to turn youth employment commitment into reality. Partnerships among governments, employer organizations, trade unions and other organizations can be instrumental in determining the most appropriate action to be taken at national and local levels for the promotion of decent work for young people. Action plans on youth employment can be used as a tool for the conversion of youth employment priorities into concrete action and to strengthen the coordination of youth employment interventions.

Which I would write – the Government takes responsibility for the full employment of all citizens and will ensure there are is a public sector available at socially sustainable living wages to any one who cannot find a job elsewhere. The Government will also enforce all industrial legislation to ensure private compliance and recognises the role of the trade union movement in redressing bargaining imbalances in the labour market.

The ILO third proposal:

Improve the quality of jobs and the competitiveness of enterprises with a view to increasing the number of jobs in productive sectors and ensuring job quality for the many young people who are currently engaged in precarious jobs, especially in the informal economy. Together with labour legislation, these measures can reduce labour market segmentation based on the type of contract and job and can help young people move to decent jobs.

Which I take as being a “faith” that the private sector will generate the jobs. Competitiveness is one of those neo-liberal code words which have seen the decline of quality opportunities for youth.

The ILO fourth proposal:

Invest in the quality of education and training and improve its relevance to labour market needs. Education and training programmes that equip young people with the skills required by the labour market are an important element in facilitating the transition of young people to decent work. These programmes should be based on broad skills that are related to occupational needs and are recognized by enterprises, and should include work experience components …

The rest of the proposal was about coordination between the government and private employment agencies and training providers.

This is a vexed area. The so-called activist agenda promoted by the OECD Jobs Study which the ILO bought into to their discredit aims to create a competitive terrain for training provision. The policy has served to undermine public education and training by forcing public schools (especially the vocational divisions) into “competing” with fly-by-night private providers who cut corners and generally aim to pursue profits rather than public purpose.

There are exceptions to this which do provide excellent skills development within the private sector but the trend is to degrade the standards rather than augment them.

Further there is a sentiment that vocational skills should be developed outside the workplace and usurp general skills development which used to be the function of schools and tertiary institutions. Even universities are being pressured into providing “training” rather than “education” by these policies. The result is that students are forced to learn “vocational” skills which are better attained within the paid-work environment (on the job) and do not achieve a broad educational understanding of the history, numeracy, literature, expression etc.

There is also pressure from the corporate sector to turn public educational institutions into merely preparation grounds for a compliant workforce to serve narrow corporate interests. For example, in Australia there is intense pressure from the mining sector to influence educational design to support coal technologies at the expense of renewables.

With all these reservations in mind, the overwhelming fact remains that youth are not gaining jobs because there is a dearth of demand rather than an insufficiency of supply (skills, motivation etc). There are not enough jobs being produced and the ultimate cause of the deficiency rests with poor policy design by governments and the failure of governments to take responsibility for job creation to ensure there is full employment.

You will note that there is very little in the ILO proposals that directly confront that reality and that urgency.

The other comment I would make relates to the proposal to include “work experience components”. This is another vexed area. The ILO know that the evidence is that training outside of a paid-work environment is usually ineffective. So they want some “work experience component” in the plans to provide some paid-work contact during training.

However, this type of component is typically abused by the private sector who see it as free labour. Work experience is usually not paid and often young workers do a range of menial tasks just to put the service on their CV.

I do not support workers not being paid and I think it is a government responsibility to ensure that all workers are paid for services rendered. If the job is worth doing then the private firm should pay for it. If it part of a training scheme then it should be built in to the paid work environment.

A more general point relates to the rise in “voluntarism” over the neo-liberal period. Governments preach the virtues of people working for free in a range of areas, often to assist the private sector make profits, when in the past the tasks were filled by paid workers.

The neo-liberals love volunteers and use all the “community service” appeals to provide free labour to the private sector.

The ILO fifth proposal:

Enhance the design and increase funding of active labour market policies to support the implementation of national youth employment priorities. Active labour market policies and programmes (ALMPs) programmes should offer a comprehensive package of services with a view to facilitating the transition of youth to decent work. Standard types of ALMPs based on single measures are unlikely to work for discouraged youth or for young workers engaged in the informal economy, especially during crisis and post-crisis periods. The effectiveness of these measures could be greatly improved by introducing mechanisms that target disadvantaged youth and by piloting programmes and assessing their results prior to their implementation on a larger scale. Funding for these measures should be increased to ensure greater support during the post-crisis period. Lack of support for these employment measures would have dramatic consequences for the current generation of young people.

More activism without any commitment to job creation. What youth need are jobs which are accessible to even the most disadvantaged and disaffected person. These jobs should have carefully crafted career-development opportunities embedded within them.

The ILO sixth proposal:

Review the provision of employment services with the objective of offering a set of standard services to all young people and more intensive assistance to disadvantaged youth. Public employment services should re-orient their services to offer “standard” support to all young jobseekers (for example, self-service, group counseling and job search techniques, including employment planning) and more intensive and targeted assistance for “hard-to-place” youth. Early interventions based on profiling techniques and outreach programmes should be developed at the local level to make the services more relevant to young people and to assist enterprises in the recruitment process. Partnerships between employment services and private employment agencies are important to support young people in their job search. Partnerships between labour offices and municipal authorities, the social partners, social services and civil society organizations are required to improve the targeting of young discouraged people and young workers engaged in the informal economy who do not usually fall within the reach of the public employment service.

Again, the proposal hints that the problem lies with the youth rather than the system. I would introduce a Job Guarantee immediately which at least would ensure there are public sector jobs available on demand to anyone youth who desired to work and could not find work in the wider labour market.

These jobs would provide a stable income to allow for adequate access to housing (should that be required and available) and allow access to public transport and other issues.

I would note that the introduction of a Job Guarantee is a minimum policy intervention. It is not a panacea for all ills. It should be the labour market safety net in all economies as an expression of minimum standards and “loose” full employment.

It is likely that a range of other support services along the lines outlined by the ILO would be useful within the context of there being enough jobs available overall. The “supply-side” measures are ineffective in the absence of sufficient jobs.

I also note that I do not use terminology such as jobseekers, which crept into the lexicon early on in the neo-liberal years as a way of attenuating the damage of the unemployment that persisted under the policy regimes that were pursued by governments under the influence of this ideology. The people they are talking about are unemployed.

You might like to read this 2006 Working Paper – The Job Guarantee in Practice – where we considered a range of issues regarding the implementation of an employment guarantee scheme. It is Australian-centric but the general principles are applicable anywhere.

You might also like to read this Report from 2008 – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy – for a related discussion.

The ILO final proposal:

Pursue financial and macroeconomic policies that aim to remove obstacles to economic recovery: Job growth will not come from labour market policies alone. Additional financial and macroeconomic measures, including bank and debt restructuring, are needed to remove the obstacles to growth.

The situation in Australia

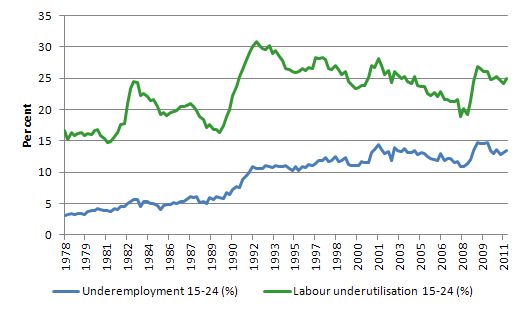

The following graph is taken from Australian Bureau of Statistics data on Labour underutilisation and shows the underemployment rate for 15-24 year olds (blue) and the broad measure of labour underutilisation (red) which is the sum of official unemployment and underemployment.

The unemployment rate is implied in the graph as the difference between the two lines.

The broad measure understates the degree of waste because it excludes participation effects which see the hidden unemployed outside of the official labour force. A reasonable estimate of that effect is to add another 1.5 to 2 per cent to the broad measure.

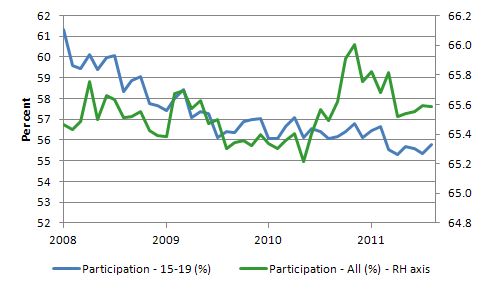

The recession has seen youth (15-19 year olds) lose ground to the adult workers in participation. The following graph shows the movement in labour force participation (Data) for 15-19 year olds (blue line and left-hand axis) and all workers (green line and right-hand axis). February 2008 was the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle (and so conceptually the maximum participation rate – given that participation is cyclically-sensitive).

The data shows that the discouraged worker effect was stronger for youth than it was for all workers. The discouraged worker effect arises when workers stop actively searching for jobs when they perceive that there is no prospect of employment (that is, when vacancies fall below some point). The statistician then excludes these workers from the unemployment category (that is, counts them as being not in the labour force). However, these workers would accept a job offer immediately should one arise.

Economists refer to this category of workers as being hidden unemployed because they are effectively equivalent to the official unemployment in that they are available for work and would start work immediately should a job arise.

The rise in overall participation in 2010 was directly the result of strengthening employment growth on the back of the fiscal stimulus packages.

As the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn and employment growth started to stall overall participation has once again fallen back but still remain above the pre-crisis levels. In part, the rise in participation overall has been attributed to older workers remaining in the workforce longer to recoup losses made during the crisis to their superannuation balances. The jury is still out on that one though.

But for 15-19 year olds it was all down hill and the participation rate is now some 5.5 percentage points below the January 2008 peak (the peak was just before the February 2008 unemployment low).

What does that imply about hidden unemployment for 15-19 year olds? If we consider all that participation rate decline to be the result of a discouraged worker effect (which will not be far off the mark given there has been no major changes in education policy in the meantime – that is, to change behaviour with respect to participation in full-time education), then the 15-19 year old labour force would be around 916 thousand in September 2011 rather than 833 thousand which was officially recorded.

That is, a further 82 thousand teenagers have left the labour force since the crises began as their employment prospects vanished. That figure has to be added to any hidden unemployment that was present at the peak of the cycle.

If you add the 82 thousand back into the official unemployed then the 15-19 unemployment rate rises to 22.6 per cent rather than the 14.9 per cent recorded as the official unemployment rate by the ABS. Add that to the underemployment rate (around 13.5 per cent – noting that the ABS only publish this for 15-24 year olds so we are approximating) – and you get a broad labour force underutilisation rate for teenagers of around 38 per cent. Read that again – 38 per cent. That is up there with the worst nations in the world – developed or otherwise.

That should give rise to headlines in our daily media and an immediate reaction and policy change from our government. The reality is that they rarely say a word about the youth unemployment situation and stand condemned accordingly.

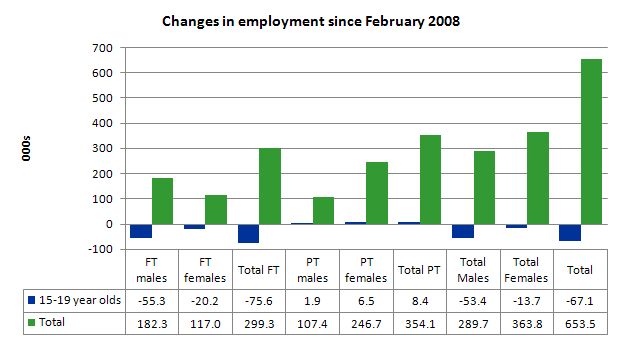

This appalling picture is completed by examining the employment data. In my monthly labour force commentary I also note the fact that since the downturn employment has fallen overall for our teenagers.

I repeat (for context) the graph from last month which shows that since February 2008, there have been 653.5 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a staggering 67.1 thousand jobs (net) over the same period. It is even more stark when you consider that 75.6 thousand full-time teenager jobs have been lost in net terms while only 8.4 thousand (net) part-time jobs have been added.

Further, around 52 per cent of the total (net) jobs added since February 2008 have been part-time.

I understand that the plight of youth in other countries is severe and in many cases life threatening. In Australia, the poverty is relative (mostly). However, there is nothing good that you can say about the labour market prospects being delivered to our youth.

The situation makes a mockery of those (like the bank economists and our politicians) who claim we are close to full employment. An economy that excludes its active teenagers from any employment growth at all is not one that is using its existing capacity to its potential.

Conclusion

As noted earlier, the longer-run consequences of this teenage “lock out” will be very damaging.

At a time when we are wasting so much of our future productive potential and our societies are ageing, the last thing we should be supporting is fiscal austerity which not only undermines prosperity in the present but also will irretrievably compromise future prosperity.

Labour markets around the world are failing the youth. At a time when we keep emphasising the future challenges facing the nation in terms of an ageing population and rising dependency ratios these economies fail to provide enough work (and on-the-job experience) for our teenagers who are our future workforce.

There is an urgent need for governments to introduce employment, education and training guarantees for the youth of the world. It will be a much worse place in the coming years if they do not.

What we need are governments who will commit to a policy platform of zero waste of all workers. We are a long way from that at present.

Saturday Quiz

I get lots of E-mail about the Quiz – some think it is too hard, others think it is too easy. That is always the problem faced by an “examiner”. I just try to make it accessible for newcomers and a bit of fun for others. Sometimes the wording is inexact for which I apologise – I assemble it fairly quickly. But it is designed to be a bit of a challenge without melting anyone’s brains.

Anyway, it will be back tomorrow – about the same as always. I appreciate the feedback but do not have much time to respond to everyone. But I value the diverse input and it makes me (try to) take care of how I word the questions to strike a balance between the quiz being too easy and too opaque.

That is enough for today!

Thanks for this commentary.

As a sometime casual high school and TAFE teacher I am appalled that children in NSW must remain in school until age 17. Some people have a very unhappy school experience and resent being babysat. They are too tired or too slow to learn at the same pace as the rest of the class and as they fall behind they become disruptive to cover their deficiencies. They need to go to work to be under the one to one supervision of an expert learning their trade skills. School and university environments can’t provide the expertise that is learnt through day to day application of the skills and techniques of your trade. Of course Victorian government is cutting the trade training program budget, VCAL, further alienating non-academic youth.

Coincidentally I note that Victoria has graduated 5000 surplus teachers annually for the past decade.

I hadn’t noted to correlation between unemployed, disengaged youth and the looming crisis of an aging population.

Like you I also abhor the rise in internships and volunteerism.

I hadn’t realised that youth unemployment in Australia was 38% but from casual observation thought that the opportunities for youth were similiar to opportunities in the 1930s

Which part of ‘there aren’t enough jobs’ do they struggle with?

The ‘current vacancies’ are in the statistics every month as are the number of people wanting work. In the UK the ratio is over 10 to 1.

Even using the most optimistic dynamic model adjustments (ie the flow of vacancies is much higher than the flow of unemployed leading to less stock build up) is simply not validated by the figures.

The private sector is failing to keep its side of the societal bargain and its time that they paid damages. I reckon as soon as you start suggesting that the private sector has to hand over cash to pay for it, they would start supporting deficit spending and ‘quantity expansion’ as a rational alternative.

How about a youth employment subsidy? In the case of the UK that could take the form of abolishing National Insurance contributions for both employer and employee in respect of youths. The revenue lost could be recouped by increasing NI contributions by adults. Or the in the case of the US, payroll taxes for youths could be abolished.

Dear Bill

Youth unemployment figures are somewhat misleading because so many young people aren’t really in the labor market. Let’s say that 80% of people 15 to 18 are in school and 50% of people 19 to 24 are in school. If youth unemployment is 25%, then it will affect 5% of people 15 to 18 and 12.5% of people 19 to 24.

Sometimes laws encourage youth unemployment. For instance, in Spain an employer has to pay to an employee whom he dismisses 1 month of salary for each year that the employee has worked for him. Obviously, this means that an employer has a greater incentive to lay off a 22-year -old who has worked 2 years fror him than a 32-year-old who has worked 12 years for him.

Regards. James

For James Schipper:

I believe you are underestimating the labour force participation rate of young people. In Canada the 15-24 year old participation rate is not somewhere between 20 and 50% as you suggest but about 66% (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-210-x/2010000/t021-eng.htm) only one or two points less than the overall rate.

The MMT lobby and Centre of Full Employment and Equity have to get an Australian political party on board with MMT and the Job Guarantee.

My suggestion is that CofFEE approach the Australian Greens with a view to a long term policy development partnership and a thinktank. Labor and Liberal are parties of the past and fully soborned by corporate capital, particularly mining corporations. The Greens will soon become the relevant, major players when predictions about climate change, species extinction and resource depletion soon become patently and obviously correct. The other parties will be seen as corporate lackeys, environmental terrorists and climate criminals when the whole of society has to pay the piper for their policy failures.

Ikonoclast, I agree that there is a natural affinity between MMT and the greens based on a common interest in sustainability and shared commitment to seeing this through. We need to be pursuing this alliance. A problem is that so far many if not most of the greens are clueless about monetary economics. and some are resistant to because they have succumbed the usual neoliberal programming, or worse the Austrian chimera. This is going to take some work.

Tom Hickey,

It is far worse. I visited the (former) “Occupy Sydney” camp on Saturday and baited a young nice-looking lady to agitate me to join a Communist group. I am I would say a bit familiar with this stuff being a former anti-communist activist but I do see some value in their ideas. (Personally I think that 99% of the Marxist critique of capitalism is true and 99% of the liberal critique of the orthodox communism is true what indeed doesn’t leave much left – but this is another story).

So when that lady had had enough of the discussion about Lenin and Felix Dzerzhinsky I asked her the last question – did she believe that governments could only spend as much as they raise in taxes. The answer was a textbook example of “sound finance”.

When even the communists believe in the neoclassical economics something must be seriously wrong with our Western culture. This is the intellectual barrier which has to be broken before any serious discussion about global problems commences and any change is facilitated.

Ikonoklast,

It would be ridiculous to approach the Greens given that their leader is a Conservative / Neo-Liberal with absolutely no grasp of macroeconomics.

Bob Brown is anti-Jobs. Always has been, and always will be.

Alan Dunn I dispute your allegation that Bob Brown is anti-jobs.

I remember that the Greens found a benefactor to fund the purchase of a timber mill which will be closed and the workers plus a few more will be employed in tourism or sustainable forestry. Can’t Google it but found that the Federal Labor government has cut funding for “the Green Jobs Crew finish in December…..the last ever of this program as it is not being refunded by the Federal ”

The Greens oppose jobs in exploitative non-renewable polluting industries like timber cutting in ancient old growth native forests, and using cheap polluting technology to build pulp mills. I heard a Tasmanian say that Gunns was closing its timber mills because it has lost its markets to cheap eucalypt forest products from South America. The forestry industry is so short sighted and unimaginative they did not charge a royalty on each seedling sent to or planted in South America.

Adam,

That shows that the money has indeed bought first-class brain-washing.

We need a new enlightenment to get out of this religious belief trap.

Adam (ak), it’s the same in the US. As Neil says, the brainwashing is thorough, and as Bill’s tests continually prove to each of us, most of us have “neoliberal tendencies,” as he calls them, that are very difficult to shake even when one knows better. This is going to be a hard nut to crack. Even Occupy Wall Street is full of “revolutionaries for sound money.” “Sound money” is kind of a countercultural fad among youth these days, like “sex, drugs and rock and roll” was for my generation. Glad I grew up then rather than now. 🙂