I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Monetary movements in the US – and the deficit

This week I seem to have been obsessed with monetary aggregates, which are are strange thing for a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) writer to be concerned with given that MMT does not place any particular emphasis on such movements. MMT rejects the notion that the broader monetary measures are driven by the monetary base (hence a rejection of the money multiplier concept in mainstream macroeconomics) and MMT also rejects the notion that a rising monetary base will be inflationary. The two rejections are interlinked. But that is not to say that the evolution of the broad aggregates is without informational content. What they paint is a picture of the conditions in the private sector economy – particularly in relation to the demand for loans. In this blog I consider recent developments in the US broad aggregates and compare them to the UK and the Eurozone, which I analysed earlier this week. But first I consider some fiscal developments in the US, which, as it happens, are tied closely to the movements in the broad monetary measures. The bottom-line is that the US is growing because it has not yet gone into fiscal retreat and the broad monetary measures are picking that growth up. The opposite is the case of the European economies (counting the UK in that set) where governments have deliberately undermined economic growth and further damaging private sector spending plans.

On Tuesday (January 31, 2012), the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published its latest the Budget and Economic Outlook – which many commentators have interpreted as representing a dire future for America but which I considered only augured well for them.

You can view all the Graphs and/or read the Full Report should you want to.

The following graph is taken from their slide package and is self-explanatory. I note they conveniently scale their horizontal axis to begin at 1946, which obviously makes the current period look the “largest”.

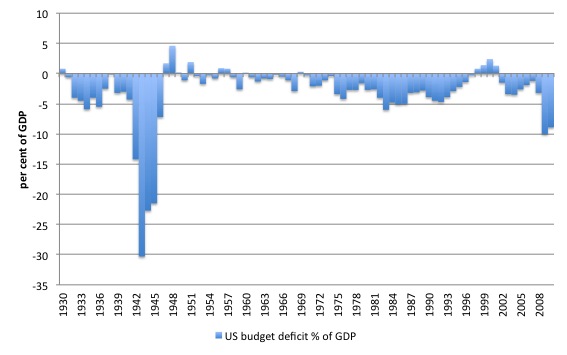

They might have also extended the time period, using the longer data series that is available, which would give a different impression. For example, using historical data available from the US Office of Management and Budget – Table 1.2-Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) as Percentages of GDP: 1930-2016 – you get the following graph from 1930:

But there is no sense to be made from staring at budget deficit graphs and concluding that one year (or years) are higher and other years are lower and that in some way means something of itself. As I have noted regularly, the budget outcome in any period (day, month, quarter, year, whatever) is endogenous – that is, it is generated by the overall macroeconomic system.

Private spending growth drives the government deficit (via the automatic stabilisers) along with discretionary spending and taxation decisions made by the relevant government. When private spending growth is strong the budget deficit will fall, other things equal. The alternative is also true.

So if a budget deficit is 8 per cent of GDP we might conclude that is a “good” outcome, if there is also full employment whereas, in different circumstances, we might conclude the same deficit is a “bad” outcome if there is 9 per cent unemployment, slow growth and increasing poverty. It means that to make any sense of a budget outcome you have to consider what is driving it.

The CBOs latest estimates show they think there will be a real GDP gap in the US of 5.3 per cent in 2012 down from 5.6 per cent in 2011 and 6.6 per cent in 2009. To put that in perspective, the CBO estimates the average real output gap since 1960 to be around 0.8 per cent (see CBO Automatic Stabilisers data).

Even taking into consideration the fact that institutions such as the CBO underestimate the output gap, the relative assessment (within their own logic) tells us that the US economy is still in very bad shape and that the $US trillion plus deficits are required to maintain the growth momentum.

So the growth is good and is starting to drive unemployment down a bit (albeit too slowly) but it has to be maintained. There is not going to be another private credit binge in the US (or anywhere for that matter) any time soon. The US can thank itself that its politicians are so moribund that they haven’t been able to politically negotiate what they want to do – impose fiscal austerity on the nation like most of the rest of the advanced world.

The other news overnight was from the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. In their – Report to the Secretary of the Treasury from the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association – (released February 1, 2012) they provided a fairly upbeat assessment of the state of the US economy.

They noted that “economic activity has continued to expand, and real GDP increased at a 2.8% annual rate in the fourth quarter, the fastest pace of growth in over a year” and:

Against this economic backdrop, the Committee’s first charge was to examine what adjustments to debt issuance, if any, Treasury should make in consideration of its financing needs. The Committee did not feel that any changes to Treasury coupon issuance were necessary at this time.

There was a lengthy discussion regarding the bid-to-cover ratios at recent Treasury bill auctions. It was broadly agreed that flooring interest rates at zero, or capping issuance proceeds at par, was prohibiting proper market function. The Committee unanimously recommended that the Treasury Department allow for negative yield auction results as soon as logistically practical.

What does that mean?

Simply that the US government is now offering bond market investors the chance to buy Treasury Bills (short-term debt) as long as they are prepared to pay the Government. Did I read that correctly? Certainly.

From the US Treasury Securities education pages provided by Treasury Direct, a branch of the US Treasury, we learn that:

Treasury bills (or T-bills) are short-term securities that mature in one year or less from their issue date. You buy T-bills for a price less than their par (face) value, (or sometimes at par value), and when they mature, Treasury pays you their par value. Your interest is the difference between the purchase price of the security and what we pay you at maturity (or what you get if you sell the bill before it matures). For example, if you bought a $10,000, 26-week Treasury bill for $9,750 and held it until maturity, your interest would be $250.

So ordinarily, an investor who wants to park their cash in a safe haven will expect some interest-bearing return on the investment. Otherwise, why not just leave it as cash.

As a result, they tender for a given nominal face-value (in the example, $10,000) which they know they willl receive at the maturity date (in the example, 26 weeks). To get the return they desire, they then put in their tender bid “at a discount” which means they would bid, in the example, $9750 and the $250 extra they get after 26 weeks is a return of just over 2.5 per cent (as an approximation).

I discussed some of these concepts in this blog – Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies.

In broad terms, for new bond issues the debt management office of the goverment receives the tenders from the bond market traders. The specific arrangements vary across nations but the process is essentially generic.

The tenders will be ranked in terms of price (and implied yields desired) and a quantity requested in volume (say, millions). The bids could be (as in the US case) specified in terms of the discount on the face value.

The debt management office then issues the bonds in highest price bid order until it raises the revenue it seeks. So the first bidder with the highest price/lowest discount (lowest yield) gets what they want (as long as it doesn’t exhaust the whole tender, which is not likely and subject to maximum quota rules). Then the second bidder (higher yield) and so on.

In this way, if demand for the tender is low, the final yields will be higher and vice versa. There are a lot of myths peddled in the financial press about this. Rising yields may indicate a rising sense of risk (mostly from future inflation although sovereign credit ratings will influence this). But they may also indicated a recovering economy where people are more confidence investing in commercial paper (for higher returns) and so they demand less of the “risk free” government paper.

But the latest missive from the US Treasury is seeking to change rules to allow investors to bid at a premium rather than at a discount on the par (face) value.

So in the example, an investor might bid $10,100 in the bill auction and thus know that in 26 weeks they will only get $10,000 back. But the point is that they know they will get that $10,000 back with certainty.

Why would the US government be doing this? Answer: there is a massive demand for US government debt from the bond markets?

But didn’t the rating agencies downgrade that debt? Answer: Yes, which just goes to show how irrelevant credit ratings assessments of sovereign debt for a currency-issuing nation are.

But is the US deficit very high and posing issues of solvency? Answer: As noted above, the US Federal deficit is forecast to be $US1.1 trillion for the 2012 financial year. It makes no sense to say the deficit is “high” or “low”.

A budget outcome is what it is. The only question is whether it is adequate for the purpose – which is defined not in financial terms but in terms of the real aggregates such as real GDP growth, employment growth, and unemployment, as key examples and the expected rate of inflation change.

Further, the US government is never intrinsically revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency despite the accounting arrangements it has voluntarily erected which make it look as though they need to tax and borrow in order to spend.

It is clear that the bond market doesn’t think there is any solvency risk when it comes to the US government. Further, it is clear from longer-debt yields that inflation expectations are anchored and very low.

The reality is that if you examine the US secondary market (which is where government debt is traded actively after it has been issued via the auction system in the primary market) then you will see that negative yields are now emerging.

Investors want to park their cash in safety and are clearly prepared to pay for that privilege. This is corporate welfare when the welfare recipient actually pays for receiving it.

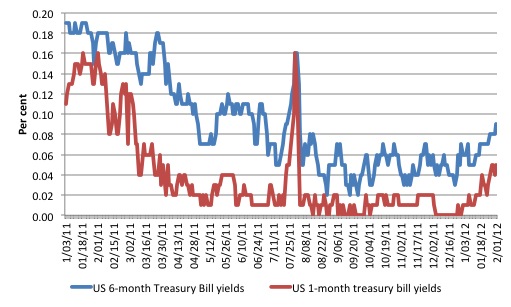

The following graph uses the Daily Treasury Yield Curve Rates data from the US Treasury and shows the yields on the 1-month (red) and 6-month (blue) Treasury Bills from the start of 2011 to February 2, 2012.

Make sure you note carefully the vertical scale – currently the yield is 0.09 per cent and in September 2011 it got down to 0.02 per cent. So the entire vertical scale is close to zero!

For the 1-month the yields yesterday we 0.05 per cent but for several days you can see the return was skating along the zero line.

Where is the mainstream macroeconomic theory when it comes to explaining all that? Answer: no-where to be seen – totally irrelevant.

And finally today (I haven’t much time to write) I return to my obsession with the monetary aggregates.

I thought you might be interested in comparing the movements in broad money in the US with developments in the UK and the Eurozone. I analysed the UK yesterday – Bank of England money supply data paints a grim picture and the Eurozone a day earlier – Latest ECB data shows how bad things have become in Euroland.

By way of explanation, the US Federal Reserve defines M1 as currency, traveller’s cheques, demand deposits and other checkable deposits. M2 is M1 plus retail MMMFs, savings and small time deposits. MMMFs are money market mutual funds.

M2 is the US Federal Reserves broad monetary aggregate. You can get the data for Aggregate Reserves of Depository Institutions and the Monetary Base and Money Stock Measures from the excellent statistics made available by the US Federal Reserve.

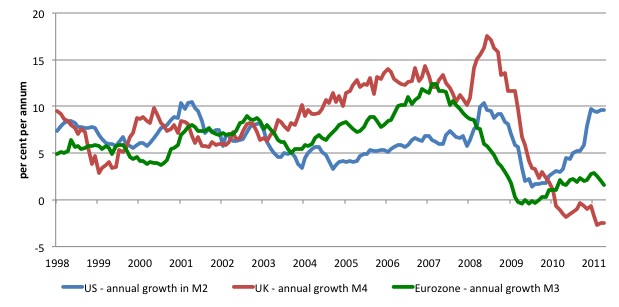

The following graph shows the movement in the respective broad monetary aggregates from mid-1998 to December 2011 for the US (blue), the UK (red) and the Eurozone (green).

Need I add that one economy is growing (not strongly but gaining momentum while the other two economies (UK and the Eurozone) are heading back into recession.

The conclusion is obvious.

In the earlier blogs this week I noted that a central tenet of the mainstream macroeconomics story that students learn from textbooks is that the role of the central bank is to control the money supply. This misconception is the first of many failings that the mainstream profession make when trying to pass on even a basic understanding of how monetary policy is implemented in a modern monetary economy to their students.

The reality is that monetary policy is focused on determining the value of a short-term interest rate. Central banks cannot control the money supply.

To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The movements in the broad monetary aggregates is adequately explained by the theory of endogenous money. which is central to the horizontal analysis in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

For a discussion of the difference between vertical and horizontal transactions in a modern monetary economy please see Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 and Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

To repeat, the “money supply” (the broad monetary aggregate however measured) is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply.

As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 (Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector) is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept. Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves.

Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as I explained in these blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

In 2006, Bernanke gave a speech (November 10, 2006) in Germany – Monetary Aggregates and Monetary Policy at the Federal Reserve: A Historical Perspective – where he discussed some of the evolution of monetary thinking among central bankers. At one point he posed the question:

Why have monetary aggregates not been more influential in U.S. monetary policymaking, despite the strong theoretical presumption that money growth should be linked to growth in nominal aggregates and to inflation? In practice, the difficulty has been that, in the United States, deregulation, financial innovation, and other factors have led to recurrent instability in the relationships between various monetary aggregates and other nominal variables.

There has been a long history of economists being “surprised” when their estimates of M1 or M2 don’t pan out in the real world. The development of broad monetary aggregates like M2 and beyond were an ad hoc response to repeated failures to accurately forecast the movements in M1.

But as Bernanke noted “over the years the stability of the economic relationships based on the M2 monetary aggregate has also come into question”.

The upshot is that these aggregates have very little relevance for policy making and only serve to excite Austrian-school devotees and remnant-Monetarists who don’t know any better.

So the divergence in monetary growth rates in the US from the UK and ECB reflects the difference in current performance of their economies. The reality is that the US government hasn’t yet imposed austerity even though public spending growth is starting to flag. There has been sufficient deficit stimulus for long enough to kick-start the economy (although it hasn’t been a very strong boot at work).

Please read my blog – The US is not an example of a fiscal contraction expansion – for more discussion on this point.

The point that arises in these contexts is the mainstream concept of the monetary multiplier. I discussed that in yesterday’s blog – Bank of England money supply data paints a grim picture.

As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates.

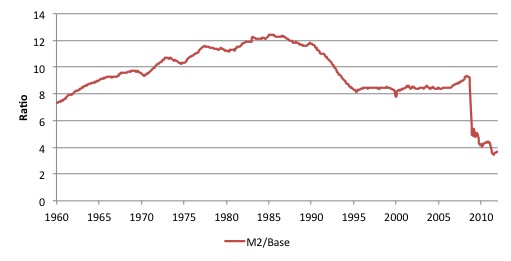

The following graph shows the evolution of the ratio of the US Federal Reserve’s M2 measure of broad money to the monetary base from 1960 to 2011. As you can see it is all over the place and renders concepts like the “money multiplier” (which logically is this ratio) useless.

In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The central bank has to guarantee reserves to the commercial banks on demand in order to guarantee financial stability. The viability of the payments system is an essential aspect of the maintenance of financial stability.

So the monetary base (currency plus reserves) always adjusts to the broad monetary aggregate not the other way around. Further, the base can move independently of the broader aggregate depending on what the central bank is doing with its balance sheet.

In other words, the central bank can expand the base at the same time as the broad aggregate is falling. That is the situation that most of the world was in a few years ago as central banks engaged in various balance sheet manouevers such as quantitative easing and other strategies via their standing facilities.

While this was going on, demand for credit from the private sector was drying up and so the broad monetary aggregates were in decline.

The is the situation still in the Eurozone and the UK. In the US, the base has expanded dramatically as a consequence of the US Federal Reserve’s asset purchase program, but more recently the broader aggregates have shown some improvement as business firms start investment (a bit).

Banks are not institutions that wait for deposits so as to build up reserves which would then allow them to on-lend at a margin in order to profit.

The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

To repeat, bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank.

Conclusion

At various times, mainstream macroeconomics (particularly Monetarism) thought that these aggregates were ideal policy control variables. The aim was to control inflation.

What they didn’t understand is that central banks cannot control the broad aggregates. Further, there is no coherent relationship between inflation and the movement in these aggregates.

However, the movement in the broad monetary aggregates do have informational content if you understand what forces drive them.

The comparison of the broad monetary aggregates tells us a story about the macroeconomic dynamics of the nations involved. Fiscal austerity in the UK and the Eurozone is damaging private spending plans and the demand for credit has declined accordingly. The negative growth in their broad aggregates reflects that.

The opposite is the case in the US at present.

There ends my trilogy of monetary aggregate blogs – for a while.

That is enough for today!

Bill

Paul Craig Roberts does a take down of the latest US GDP numbers in his article Economics 101 which seems fairly reasonable (although his inflation hysteria at the end clearly reflects his hard money bias). If his analysis is correct, could I assume that something similar might be done to the UK and Eurozone numbers which would keep the ratios between the three fairly intact?

First, I wonder what the gold bugs think of people paying for the opportunity to own the dollar. Remember, we should buy gold because the dollar might collapse, or least hyperinflation.

Next, tell me what you think of this scenario:

-the US economy with an 8% budget deficit begins to grow enough that

-corporations begin to spend some of their $2 trillion to update their infrastructures

-people begin buying cars to replace extremely used older models

-the US rich dump loads on the economy to buy politicians

-and all this with China’s resumption of growth and an increase in the value of the dollar helps the

European economies begin to grow

– thus we have a recovery.

By the way, wouldn’t the US charging for the opportunity to own dollars be deflationary?

“To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example.”

Unsure as to which central bank “controlled” the stock of gold.

Hi Bill,

As money aggregates are concerned, could you pls elaborate an the TARGET2 saldos in the EuroSystem. Are the discrepancies per MMT really a problem as indicated by Mish

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2012/02/bundesbank-228-billion-euros-in-debt.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+MishsGlobalEconomicTrendAnalysis+%28Mish%27s+Global+Economic+Trend+Analysis%29

or just a accounting necessity?

Regards from Austria

(currently in crisis-shaken Spain)

Bill, I mention you and CofFEE in this essay. Hope you like it:

http://www.neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/02/doing-what-needs-to-be-done-facing.html

I’m still puzzled about the mechanics of these Treasury auctions and the bidding process. Why would anyone be willing to buy a negative interest T-bill? If they already possess some dollars in any form, which they must in order to by the bill, isn’t it always preferable to hang onto those dollars rather than purchase a negative interest bill. No matter what is happening with real rates, a 0% nominal interest yield is preferable to a negative nominal yield.

Is this a case where the bank fees or “storage costs” for ordinary bank deposits are so high that the dollar holder is willing to buy a negative interest bill because they lose less that way than they lose by keeping money in a bank account?

Or are the dealers willing to do this because they expect the Fed to vacuum up all the T-bills? So they pay $10,250 for a bill that matures at $10,000. But then the Fed buys the bill from them for, let’s say, $10,300. The dealer still makes $50, and Treasury has a liability of only $10,000 in exchange for the $10,000 in cash assets it received.

So the net effect is $300 in net financial assets created by the Fed, with $250 credited to the Treasury and $50 to the private sector.

If that’s what’s going on, then I think I like it. The phony aspect of the “debt” that treasury owes to the Fed tends to be used by fiscal hawks to bamboozle the public, even though it is insignificant. If the Fed and Treasury can accomplish the same functional effect without increasing the deficit, and with private sector dealers getting a smaller cut, then that looks good to me. It moves us closer to a system of direct central bank crediting of Treasury accounts in order to expand deficits.

However, if the whole operation accomplishes nothing but a “paying down” of the debt, with no expansion of net financial assets, it won’t be worth anything.

Where I said,

“The dealer still makes $50, and Treasury has a liability of only $10,000 in exchange for the $10,000 in cash assets it received.”

I meant to write:

“The dealer still makes $50, and Treasury has a liability of only $10,000 in exchange for the $10,250 in cash assets it received.”

@ Dan: I was wondering the same thing. My thought was that somehow the balance sheet expansion by the bank improved their capital position and therefore allowed them to make more profitable loans by having Treasuries on their balance sheet, even if they had to pay a small amount of interest for them. Or perhaps they just improve their balance sheet RWA enough that they are willing to pay even if they aren’t going to make additional loans?

“Is this a case where the bank fees or “storage costs” for ordinary bank deposits are so high that the dollar holder is willing to buy a negative interest bill because they lose less that way than they lose by keeping money in a bank account?”

Dan,

This is because buyers of T-bills face the risk that the banks with which they hold their funds can close down. Deposit insurance is restricted to $250,000 per account. Even if it were higher, it may take the government some time to disburse the funds if the bank shuts down. So better buy T-bills.

Two comments:

1. The factors determining the money supply are probably even more nuanced than Bill’s description here. While it is literally true as Bill says that changes in the quantity of bank credit drive changes in the money supply, the demand for money and the demand for *borrowing* are able to vary independently. Not all borrowing occurs through banks. So the private sector has the ability to expand or contract the money supply through its portfolio decisions independently from changes in its demand for borrowing. The Circuitist literature seems to support this — just an interesting side note that is still consistent with Bill’s post.

2. I wonder whether Bill agrees with Warren Mosler that “The currency monopolist is necessarily price setter. The price level is necessarily a function of prices paid by government when it spends, and/or collateral demanded when it lends.”

If so, then it seems to me that interest on government bonds is welfare only if the interest rate exceeds the inflation rate. But if real risk-free interest rates are negative, a more accurate portrayal seems to be that of a government tax on financial assets. I am making no value judgement in that statement, as perhaps this is a good place for a tax… but I do wonder whether if the government is effectively taxing financial assets via negative real interest rates then maybe it should have a parallel and comparably-sized tax on tangible assets (gold, real estate, etc). This is just conceptual, as I recognize there would practical hurdles.

This is because buyers of T-bills face the risk that the banks with which they hold their funds can close down. Deposit insurance is restricted to $250,000 per account. Even if it were higher, it may take the government some time to disburse the funds if the bank shuts down. So better buy T-bills.

Thanks Ramanan. Do you think this demand for more T-bills is coming from Europe? Or is it domestic?

Dan,

Good points. I haven’t seen the demand data for some time now.

But highly possible it is from Europe. In fact, the financial stress indicators made by investment banks’ research teams still show that risks levels perceived by the markets are high.

By the way this is not the first time yields are turning negative in the US. They did so in 2008 but in the secondary markets. Its the first time that in the primary markets yields can turn negative. It also happens with German and Swiss T-bills. In fact in the latter, one can sometimes see even 2-3y negative ask yields in the secondary markets.

Or maybe the Fed is just asking their bussiness partners to play this role of “blind confidence” to maintain the neo-liberal show for a long time in town…. maybe I’m just getting conspiranoid….

“What they paint is a picture of the conditions in the private sector economy – particularly in relation to the demand for loans.”

Why should anyone or any entity want a loan?

Is there any reason a no private debt, no gov’t debt, no current account deficit economy isn’t possible?

Hi Bill,

with respect to the US labour market, I’ve been wondering about Claims (in the contect of Emp/Pop ratio). The better results for Claims (to below 400k) is getting a lot of people excited, but it would appear that at such a low operating level for the labour market currently, there are not many left to fire! Then you have all the poor ‘internals’ that go with it, like movements from unemployed into ‘out of the workforce’ altogether, average length of unemployment at all time highs, and so on. And therefore, Claims below 400k isn’t signifying the strength many claim it to does. Have you done any work on this?

Dear Fed Up (at 2012/02/03 at 10:38)

There is no reason why all the individual balances could be zero. Except it is very unlikely because of the different patterns of production, trade and resource availability.

best wishes

bill

Dear hbl (at 2012/02/03 at 7:27)

Thanks for your comment.

You said:

But the fact that bonds have (in secondary markets) and might (in primary markets) sell at a premium to par reflects the demand side. The lenders are imposing a “tax” (if you want to call it that) on themselves. Moreover, you might be mixing real and nominal.

You have to add to the real income received the “insurance premium” that the investors get from not having to take the risk of having their funds disappear altogether if a bank was to collapse, for example. The real return then might not be negative.

But the point about other assets is reasonable.

best wishes

bill

Bill, thank you for the response.

“But the fact that bonds have (in secondary markets) and might (in primary markets) sell at a premium to par reflects the demand side. The lenders are imposing a “tax” (if you want to call it that) on themselves.”

I’m having trouble seeing it in that light. To keep it simple, consider the short end of the yield curve (e.g., 4 week treasury bills). The yield historically tracks fairly closely to the central bank’s federal funds rate. Is it really fair to say the demand side is choosing that t-bill rate itself? Perhaps within a narrow band it is, but the general vicinity of that rate seems entirely controlled by the central bank’s current overnight rate settings. The central bank should know that arbitrage is an inevitable outcome of its rate setting and I thought I’d even seen you state before that government policy essentially controls risk free rates across the yield curve.

As for whether the private sector is benefiting from an implicit “insurance premium”… suggesting that this is built in seems as I understand you to be a suggestion that under a government seeking to best serve public purpose there should be no such thing as risk free financial assets at all (even ones that pay no interest) unless someone pays for that privilege. If that is your implication, I guess I’m a little surprised, but I acknowledge it would be a fair position for someone to hold.

Dollar rallies as US jobs jump and Employment Report: Blatant And Outrageous Lies (note KD is a “deficit hawk” but he may have a point here)

In January, those not in the labour force apparently rose 1 177 000. I’ve no doubt that the US deficit is driving some measure of recovery but for nearly 1.2 million people to fall out of the official stats suggests a larger surge in hidden unemployment rather than a strong surge in recovery.

Hello Bill,

Following your recent blog about M3 in the Eurosystem which made me ponder for a few days (thanks for that!), I have been reading about money aggregates. It was easy to find description tables about the various aggregates but I did not find this satisfactory. For one thing, I really cannot understand the emphasis on the currency base. Indeed, nowadays, most commercial transactions are totally immaterial and money is stored by means of computer data. So why should we care about bank notes and coins when most households and firms use credit cards, checks and wire transfers? Is it not the case that the currency base is the remnant of an age now defunct?

Second question along the same line: why are the Stock Market and the Real Estate Market not taken into account when measuring money aggregates? The stock market is just as liquid as any other paper. If you sell some shares, then your account is credited within 1 or 2 days. Why make a difference between MMF shares and stock shares? Real estate is obviously much less liquid, but could it not be included in a broader measure on money? And further, should not all major markets (gold, oil) be included in a macro money aggregate? I would really like your comment on this.

Tracking aggregates of all major markets would perhaps be useful in order to track where the credit issued by the Central Bank eventually goes. It is often said that easy credit from central banks find its way into speculative bubbles such as the oil and gold markets? Would not new aggregates allow us to trace where the newly created money is going?

Cheers from Paris

I said: “Is there any reason a no private debt, no gov’t debt, no current account deficit economy isn’t possible?”

bill said: “Dear Fed Up (at 2012/02/03 at 10:38)

There is no reason why all the individual balances could be zero. Except it is very unlikely because of the different patterns of production, trade and resource availability.

best wishes

bill”

And, that is why there are currencies that can adjust? Targeting NGDP and/or price inflation misses those other things and can allow a currency to be overvalued or undervalued in relation to time.

Yanai said: “So why should we care about bank notes and coins when most households and firms use credit cards, checks and wire transfers? Is it not the case that the currency base is the remnant of an age now defunct?”

Assuming by bank notes you mean paper currency, I believe you are asking the medium of exchange question. What is the difference between paper currency and coins (currency) and demand deposits. IMO, the most important one is currency is not directly defaultable, while demand deposits are.

And, “Second question along the same line: why are the Stock Market and the Real Estate Market not taken into account when measuring money aggregates? The stock market is just as liquid as any other paper. If you sell some shares, then your account is credited within 1 or 2 days. Why make a difference between MMF shares and stock shares?”

because stocks and real estate can go down in value while medium of exchange does not directly go down in value unless defaulted on (I expect my demand deposit, checking account, and money market fund to be redeemable 1 to 1 for currency). In certain circumstances, that may not be true.

Thanks Fed up for your reply. What you say makes sense.

Still, in our day and age, it seems stock, commodities and real estate markets have an influence on the distribution of credit throughout the economy. We know that from experience. If a homeowner goes underwater, then he/she cannot borrow against the value of his/her home whereas, before the crisis, it was possible to obtain consumer loans based on the value of houses. The same applies to companies: if a company has strong market value, then it will be able to borrow easily. So clearly, those markets have an impact on the distribution of credit.

So my question is: if money is both credit and a store of value, why is there no broad measure which includes all other means of storing value and gaining access to credit? Wouldn’t the creation of this broad aggregate help understand the formation and burst of asset bubbles? Example: if the FED had included the real estate in its calculation of broad money, it would have seen that its policies were fueling an asset bubble i.e. that the expansion of credit was not directed towards the expansion of production. Last year, it seemed QE2 was fueling an oil bubble.

Yanai, check back later.

Yanai said: “Still, in our day and age, it seems stock, commodities and real estate markets have an influence on the distribution of credit throughout the economy. We know that from experience. If a homeowner goes underwater, then he/she cannot borrow against the value of his/her home whereas, before the crisis, it was possible to obtain consumer loans based on the value of houses.”

I believe private debt and gov’t debt should both be zero. However and if there is debt, then it should be based on the ability to repay, not on collateral/assets.

And, “So my question is: if money is both credit and a store of value, why is there no broad measure which includes all other means of storing value and gaining access to credit? Wouldn’t the creation of this broad aggregate help understand the formation and burst of asset bubbles?”

I like to use total debt from the fed’s flow of funds. I believe it can also be found at St. Louis Fred site as TCMDO. I believe the question you are asking is what happens to the medium of exchange from debt/where does it go. Good question to have answer(s) to unless the fed was listening to F. Mishkin.

“if money is both credit”

I don’t like the term money. There are too many definitions. I prefer medium of exchange. I don’t believe medium of exchange should be credit/have a bond attached to it.

About the first two graphs, is it possible to have a graph(s) that includes total debt (private AND gov’t) nominally and vs. real GDP?