The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Rescue packages and iron boots

Today, I thought I would provide some background to the Euro crisis to advance some understanding of why the conservatives in Europe are advocating highly destructive solutions to their crisis. So I went back to some notes that I have accumulated over the years to try to put the sort of nonsensical fiscal rules that are now being proposed by very influential German economists into some sort of context. What you will see is that the context doesn’t in any way help to justify the rules. They are crazy by any reasonable assessment. But at least you will see them in a wider context. I hope.

On April 29, 2010, the German-based Ifo Institute for Economic Research, which is located in Munich released a document – Euro rescue package rewards speculators and hurts German interests – summarising the views of one Professor Hans-Werner Sinn, who is the President of that institute.

Further, his latest pamphlet – Euro-Krise – is in German but basically shows how great Germany has been in keeping its public debt down and deficits controlled while the south have been evil.

Let she/he who is without sin cast the first stone! Sinn is definitely part of the Eurozone problem.

He has built up a long history of being opposed to the Welfare State. For example, in this 2007 paper he argues that changing patterns of world trade has reduced the “equilibrium price of labor in western Europe” but the welfare state minimum rules prevents the necessary adjustment from occurring which prolongs unemployment.

So a classic mainstream argument that unemployment is caused by excessive real wages and government regulations. If you took time and analysed the shift to profit share over the period he analyses you will realise that productivity was running ahead of real wages. So where was the real wage overhang?

In this 1999 paper paper, he claims the German pension system needs to be supplemented by privatised saving schemes. In this 2000 paper, he “advocates the home country principle for the treatment of immigrants” to reduce the strain on the German welfare system.

Sinn sits in the German free-market tradition of Ordoliberalism, which in modern parlance is very much like conventional neo-liberalism and indeed most people simply refer to Ordoliberalism as “German neo-liberalism”.

Ordoliberals are free-market liberals but not free-market libertarians in the Austrian-school sense. As an example, the Austrians advocated a non-intervention approach to the current crisis on the basis that all government growth is undesirable and will delay the market resolution. The ordoliberals argue that the government is largely to blame for the crisis (by not allowing competition to work properly) but that government support in the crisis was necessary given the scale of the downturn. But both free-market camps are obsessed with the notion that the patient, now probably saved by the emergency public interventions, needs to be weaned of its drug dependency.

You can read a lot of ordoliberal economic writing in their main journal – ORDO. It is a very German-centric school of free-market thinking. At times, you will not be able to tell the difference between this camp and the Austrians.

To understand the EMU crisis that is now worsening and will ultimately force major changes on the way they have designed their system or result in several nations exiting the union, you have to understand the ordoliberal tradition, which emerged in the C19th. More recently, it fused with the events of the 1920s and 1930s in Germany to become a form of “German monetarism”.

Germans have been very influenced (scarred one might say) by the hyperinflation of the 1920s and the nationalist socialist era that followed it. Even during the Post World War II period when other nations were pursuing “Keynesian full employment” economic policies, the Germans ran tight budgets and maintained growth by keeping their currency low to boost exports.

In the Post World War II period, the C19th ideas (that is, ordoliberal views) where the state only provides a broad institutional environment that maximises the freedom and self-regulation of the private sector were refined. These ideas were reinforced by the antagonism to broader government intervention which was developed in the 1930s by the so-called Freiburg school which played the “state = nazi card” to perfection.

So the ordoliberals eschewed Keynesianism because it would be inflationary and they wanted to avoid any hints of government intervention (Nazi-effect). They also aimed to build a strong private sector driven by investment in traded-goods industries. In general, free markets were held out as the optimal way to allocate resources.

Any “social welfare” leanings were heavily influenced by the Catholics (the All Souls idea) which sets it apart from the broader social-democratic visions of the welfare state. That is, they were not very liberal at all and were saturated in conservative morality.

The Germans did experiment with a more traditional Keynesian approach in the 1960s (for example, the Stability and Growth Law in 1967) but it was always tightly controlled by the all-powerful central bank. The emphasis on price stability remained and has dominated German macroeconomic policy and the way their academy has developed.

The Bundesbank always dictated the deficit limits. But the OPEC oil price hikes pushed the macroeconomic debate in Germany back towards the ordoliberal tradition. In the rest of world the resulting stagflation opened the door for the neo-liberal dominance of macroeconomic policy.

I thought I would give you some background on the evolution of macroeconomic thinking in Germany prior to the creation of the EMU. What you will now understand is that the way the EMU was constructed – the fiscal rules – the lack of a fiscal redistribution system to cope with asymmetric shocks – the strong deflationary stance taken by the ECB – is completely consistent and an extension of the ordoliberal conservatism that has dominated macroeconomic policy in Germany for years.

All the EMU did was impose this free-market blend on other nations that had no tradition (or probably no taste) for it. The Bundesbank simply morphed into the ECB (based in Germany nonetheless).

However, I wouldn’t want to say that the extremely conservative Bundesbank macroeconomic philosophy survived completely. For example, the German wages system was tightly controlled by the Bundesbank but managed to keep trade unions happy while given the central bank an effective cost brake. This system has not been transferred in the EMU. It was claimed that with such disparate labour market conditions including substantially different productivity levels such a system was not appropriate. Read: it would have rewarded the southerners too generously.

This clearly took one policy tool off the central bank under the EMU which then had to run even tighter monetary policy than the Bundesbank would have done given its supporting wage brake. This meant that the ECB has adopted even more deflationary monetary stances than it might have.

Anyway, ordoliberals believe in a strict separation of monetary and fiscal policy. The former should be administered by a completely independent central bank with the sole focus being to maintain low and stable inflation via monetary discipline. No political pressure should be placed on the central bank.

On the latter, they argue that budgets should be balanced although it is unclear exactly over what time span this should be achieved. There are several views.

Anyway, Hans-Werner Sinn is implacably opposed to the “rescue package” that the EU bosses worked out recently. He considers it not to be “contrary to German interests”.

His view is that there is “no systemic crisis of the euro” and claims it is overvalued (its “true value lies at around 1.14 dollars” in ppp terms). As of this moment the Euro is sitting on 1.23 against the USD. Sinn said:

It was not the euro that was endangered in the crisis but rather the ability of the European debtor states to continue to finance themselves on such favourable terms as Germany … In addition many banks, in particular in France, have great problems because the market value of their claims against the debtor countries were at the risk of falling further. For this reason the French especially pressured Germany to accept the rescue package.

He claims that if the rescue package is executed then the Germans become liable for the debts of other states which is strictly banned under Lisbon agreement (which defines the EMU rules).

He considers that the southern Europeans have “profited from favourable interest rates and were able to finance an artificial economy boom on credit”. He considers that the higher financing rates in recent months for these governments would have “ended the artificial boom” and the rescue packages prevent this market adjustment from occurring.

But he claims that German savings have been flowing into the artificial southern European boom which has slowed its own growth. What is needed now is an interest rate adjustment to retain these savings within Germany and force the other debtor nations to adjust via austerity.

In a paper he released on April 29, 2010 – Viewpoint: How to Save the Euro – Sinn goes into more detail about his preferred fiscal policy stance.

When you first read it you will think it is deplorable. Every subsequent time you read it you will conclude the same. But I hope the little introduction I gave about the ordoliberal tradition at least will allow you to see why these characters advocate such deplorable anti-humanity policy positions.

In that earlier paper, he claimed that the “Greece-triggered crisis has taught Europe a bitter lesson in economics”.

He notes that if a nation:

… has its own currency, its attempt to sell bonds will eventually come up against investors’ skepticism. For this reason, in their pre-euro days, many European Union countries had to devalue their currencies now and then in order to sell more merchandise and real assets and thus raise the necessary funds. Admittedly, only rarely were whole islands flogged on the market, but quite a bit of real estate was indeed sold at the time by such countries as Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal.

Well, if a nation has its own currency, ultimately, “investors’ skepticism” (that is, the attitudes of the bond markets) is irrelevant to the fiscal viability of such a government.

The point is that it is always assumed by mainstream macroeconomists who now operate within the neo-liberal tradition that the bond markets are the ultimate constraint on government net spending. The constraint is, of-course, voluntary. Sovereign governments could operate free of this constraint whenever they like subject to legislative or regulation reforms.

The fact that governments continue to allow the bond markets to dictate terms (to some extent) and impose real costs on the citizens they pretend to represent is a testament to the victory of conservative ideology. They lost the gold standard, then the US-dollar standard but kept some of the artefacts. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

But Sinn’s other point is clear although he would not agree with my interpretation of it. A flexible exchange rate is highly preferred as a way of freeing up fiscal and monetary policy to attend to maximising domestic outcomes – growth, employment etc. If the exchange rate is pegged in any way at all, then these policy tools become compromised by the need to maintain that peg.

Then much harsher methods are required to remain competitive and in modern parlance we can summarise those as – “the race to the bottom” – that is, deflationary wage policies and more onerous work intensity.

Sinn then juxtaposes the prior adjustment possibilities with the situation in the EMU today.

Today, some of these countries, foremost Greece, interpret their membership in the European monetary union as having the right to pay for their imports with bonds rather than real resources. They are neither willing to offer investors higher yields, nor to render themselves somewhat cheaper, and thus more competitive …. they now demand contingency loans from other euro state, which the market is not ready to grant them … In the end, instead of doing something to reciprocate for all their imported smartphones, airplanes, and cars, they want to receive part of these goods as some sort of donation.

If we take out the racist element that underpins a major part of the within-EMU debate at present (and the second world war hostilities that continue), then what are we to make of this argument.

All nations have to earn export revenue in foreign currencies in order to import. This is independent of whether you run a currency float or not. A currency float can make it easier to do this by maintaining competitiveness against rivals. So you have to give up some real resources that you could otherwise consume yourself to get the capacity to buy imports.

But when most of the trade is within a currency union, this gets more complicated. For any nation in the EMU, the Euro is “effectively” a foreign currency because none of them issue it. The Greeks have been able to run “trade deficits” because other EMU nations have desired to provide them with real goods and services (the phones, cars etc) in return for euro-denominated claims on Greece. The market has sanctioned that.

The demand for German military hardware from Greece has allowed the German economy to grow faster than it would without net public spending. So the so-called Greek “profligacy” has been making the German government look better than it otherwise would. Presumably, the real estate booms have also transferred a lot of real goods (land, tourist infrastructure) to German interests. Certainly, in Spain, there has been a massive increase in foreign ownership of Spanish land and housing and the associated infrastructure.

Further, a nation that pegs its exchange rate or gives up its currency has an additional problem. It also has to “finance” its own government spending by raising taxes or borrowing in the currency it spends in. In the EMU, the national central banks can create euros but cannot use them to buy primary issue government debt. So if the private markets will not buy the primary issue bonds as is the case in Greece at present then the national banks cannot do much in the secondary markets.

So once the Greeks entered the EMU, they gave up currency sovereignty and like all EMU nations, became exposed to solvency risk. That is, what the crisis is really about – the surrender of sovereignty. It is thus a misnomer to call it a sovereign debt crisis because none of these nations are sovereign in any meaningful way from the perspective of macroeconomics.

The truth in Sinn’s statement is this: under the flawed design rules of the EMU, the bailouts are futile. Within those rules, the only way Greece can continue is to attempt an internal devaluation. Why they would want to do that rather than exit the whole failed system speaks to the victory of the flawed mindset of its political class. This class enjoys the trips to Brussels it seems.

Hans-Werner Sinn then has a better remedy. He wants a “new Stability and Growth Pact”:

… one that would be formulated to impose ironclad debt discipline. What is needed are modified debt rules, hefty sanctions, and, most of all, a system of rules that automates the levying of penalties, leaving no room for political meddling.

Okay, so the classic ordoliberal response. The only thing that really matters is price stability. That is easy to accomplish if you permanently scorch your real sector and deflate all sources of nominal pressure. The tight monetary policy will also stop any inflationary pressures coming from the exchange rate.

The harsher fiscal rules that Sinn advocates are summarised as follows (read his paper for full outline).

First:

the permitted maximum for the deficit-to-GDP ratio should be inversely proportional to the debt-to-GDP ratio, in order to establish an early incentive to apply debt discipline.

So for nations that violate the 60 per cent Maastricht Treaty debt ratio rule, they would have to run deficits a certain percentage below the Treaty deficit rule of 3 per cent.

His specific rule applied to Greece, would see it have to run surpluses of at least 1 per cent of GDP until the debt ratio fell to 60 per cent. Clearly, this would cause a major reduction in GDP which would make it easier in an accounting sense to accomplish the target. But with automatic stabilisers operating and continually pushing the budget into deficit, the extent of the discretionary contraction that would be required to meet the 1 per cent of GDP rule would be massive and untenable.

Sinn’s discussion is biased heavily by the notion that the EMU nation budget deficits are all discretionary. And casting the ordoliberal morality over the issue – that must mean profligate and wasteful spending by inefficient governments that allocate resources outside the discipline of markets.

All the usual criticisms about the free-market attack on government provision can be made here but they are well known so I will leave them. There is no monopoly on wasteful, corrupt and profligate spending in the public sector. The recent crisis has taught us very well how poorly private markets allocate resources.

But the substantive point is that the world economy has been hit by the worst crisis in 80 odd years. There has been a massive private spending collapse and the financial systems went to the brink of total collapse. Only government intervention saved us from that end. And the extent of the crisis was such that the budget positions in almost every case had to move into significant deficits (well beyond the upper Stability and Growth Pact limit) to support private saving again.

The whole of the Eurozone cannot be a net exporter. Most nations will run trade deficits. That means if the private domestic sectors are to save overall (as a sector) then their governments have to run deficits. Currency union or not.

The private debt-binge in southern Europe now requires adjustment – rising saving ratios are the only way for that sector to pay down the debt. That means this adjustment has to be supported by deficits. Imposing major fiscal austerity is exactly the opposite policy position that is required.

But over an extended period, fiscal policy has be like a rubber band – be able to expand and contract to meet the fluctuations in private spending. Otherwise, the real economy adjusts downwards when private spending fails and the fiscal support is inadequate.

That rubber band will almost always violate the rules being proposed. So the only conclusion you reach – which is consistent with the ideological disposition of the ordoliberals – is that they value price stability over everything else and unemployment is not something particular that we should worry about. It is a necessary cost of maintaining nominal discipline.

The problem is that nominal discipline can be maintained without harsh real adjustment – that is the basis of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Please read the blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for further information on that position.

Sinn’s second requirement is that:

A tax, proportional to the breach of the deficit and indebtedness rules, should be levied on euro-zone members’ national debt. The level of the tax would be set for each country based on the spread charged by the markets in the days before the euro. The tax should be high enough to ensure that it is not possible for a given country, when compared to the bloc’s most stable country, to acquire excessive debt more cheaply than they would have been able to prior to the introduction of the euro.

Once again, scorch the nations that are suffering the largest collapse in private spending.

He goes on to argue that “privatizable state assets” should be offered as collateral for any sanctions imposed on nations in breach of these fiscal rules. He also would transfer power to Eurostat for determining when sanctions would be applied to avoid a nation like Greek fudging their data.

He wants a “European Public Prosecution Service” to be established “that is obliged to take legal action independently against breaches of duty by the respective national statistical offices or EU bodies and bring the cases before the European Court of Justice.”

Any further debt assistance (within these rules) should only be provided by the EMU nations at market rates and with “privatizable state assets” offered as collateral.

When a nation finally crumbles under this iron boot of fiscal discipline – (breaching the rules “five or more times in 10 years”) – they “should be expelled from the monetary union.”

Conclusion

I guess it must be the bad weather in Northern Europe that leads to this mindset.

Rules like this are anti-people and will always fail because of that. Nations operating within this sort of fiscal straitjacket could never reasonably meet the challenges of a major spending collapse that we have witnessed over the last few years without soaring unemployment. Even Spain which conducted fiscal policy within the Maastricht rules up until the crisis is now experiencing 20 per cent unemployment. Imagine what its unemployment rate would be if they had to follow the rules that Sinn proposes.

The irony is that the political philosophy of ordoliberalism and neo-liberal are part of the tradition that developed in the second-half of the C19th century as a specific counter to the growing popularity of Marxism.

The practical application of these philosophies to the macroeconomy will ultimately be the best marketing tool for Marxists and other solidaristic ideologies. You can only tread on people with your iron boot for so long.

The riots in Greece suggest their fuse is relatively short. But civil unrest in Ireland is starting to appear (for example, protests over the Irish contribution to the rescue package being higher per capita than for Germany).

Digression: Rising US jobless claims – should be careful though

Yesterday (May 20, 2010), the US Labor Department published the latest “Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Report” which shows the number of people lining up for unemployment benefits in the US.

The release said that:

In the week ending May 15, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 471,000, an increase of 25,000 from the previous week’s revised figure of 446,000. The 4-week moving average was 453,500, an increase of 3,000 from the previous week’s unrevised average of 450,500 … The advance number for seasonally adjusted insured unemployment during the week ending May 8 was 4,625,000, a decrease of 40,000 from the preceding week’s revised level of 4,665,000. The 4-week moving average was 4,642,500, a decrease of 9,500 from the preceding week’s revised average of 4,652,000.

This led to news reports all around the world predicting the worst. Take the report in the UK Times today which carried the headline – Shock rise in US unemployment.

The Times report said:

New claims for unemployment benefit in the US rose unexpectedly last week, leading to fears that the job market could prove one of the biggest barriers to economic recovery … The figures further highlight the fragility of the economic recovery as unemployment, currently running at 9.9 per cent, remains one of the biggest obstacles to a sustained domestic recovery.

Dan Greenhaus, chief economic strategist with the New York research firm Miller Tabak & Co, said that the level of jobless claims was higher than anticipated, given the length of time of the recovery.

“We remain concerned about income growth and stabilisation in the pace of equity market appreciation, both of which are likely to slow the pace of consumption in the coming quarters,” he said.

Ian Shepherdson, chief US economist, described the latest jobless figures as “horrible”.

This could be a good Saturday Quiz question. How many readers will see this data and conclude the same as The Times US business correspondent who wrote the article and the two “experts”?

Answer: the conclusion is probably wrong.

Even the title is misleading given that the data just shows an increase in claimants which could occur with falling unemployment as the proportion of claimants rises. In the US case, for reasons I note below, it is likely that US unemployment is rising but you cannot infer that from the data.

But if you understand what is going on in the US at the moment and also understand the dynamics of recessions you will not fall prey to these sorts of reports. I have spent a long time researching the dynamics of recessions in my career to date and although each one is a little different in various ways the broad dynamics are the same.

The latest detailed Labour Force data published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics gives you some insight into what is happening.

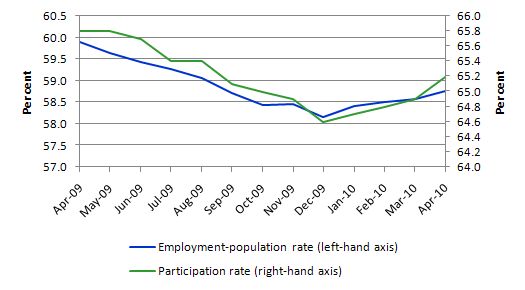

Consider the following graph which shows the leading labour market indicators – the employment-population ratio (blue line), which is, computed as total employment as a percentage of the civilian population; and the labour force participation rate (green line), which is the labour force as a percentage of the civilian population. They are both cyclical as a result of their numerators (employment and the labour force, respectively). But they are considered a more reliable measure of how things are going because the denominator in each (civilian population) is not-cyclical (much).

December 2009 appears to have marked the turning point in the US labour market and with employment now growing again workers who were previously classified as being out of the labour force on activity grounds (that is, they had given up looking because there were a dearth of jobs) are now starting to come back into activity. That is what the rising participation rate tells you.

An economy in the early stages of recovery where employment growth is positive and participation rates are rising will generate rising unemployment. That is, the employment growth is not yet strong enough to absorb the growth in the labour force. This is also a common characteristic of rapidly growing new regions – where despite strong employment growth, the attraction of the area promotes a much stronger labour force growth and unemployment rises in that area.

So the data is telling me at this stage that the US labour market is improving. I realise the BLS data is for April and the claimant data is a little more recent but I suspect the trends that the BLS data is showing are driving the rising claimants

The rising participation rate is evidence that the hidden unemployed who left the labour force at the height of the recession are now seeing better job prospects and are thus actively looking for work again. Remember that the labour force survey asks various questions before deciding whether a person is employed, unemployed (both sum to the labour force) or not in the labour force. If a person is not considered to be employed but is willing to work and actively seeking work they are considered unemployed. If they are willing to work but not actively seeking work they are considered not in the labour force and do not count towards the unemployment rate.

How much does this affect things? The following graph simulates what the unemployment rate would have been had the participation rate of December 2009 (the trough) had not changed. It was a low of 64.6 per cent then and in April had risen to 65.2 per cent. So I simulated the lower labour force and using the actual employment data recalculated what the unemployment rate would have been at the lower participation rate.

The current US unemployment rate is 9.9 per cent and if the participation rate had not have improved then it would be 9 per cent. So while it looks bad that the unemployment rate is rising, it actually, in the early stages of the recovery, a sign that things are getting better.

However, I don’t want anybody to think I consider this situation to be even marginally acceptable. The US government should immediately make an unconditional offer of work at the minimum wage (revised upwards considerably to represent a genuine socially-sustainable minimum) to anyone who wants to work. That would improve things much more quickly than taken the slow, grinding market-driven recovery that they seem to be content in following.

The lesson is that you need to be careful when analysing data because sometimes things are not what they appear.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

You might be interested …

Niall Ferguson stopped by the Peterson Institute last Thursday to deliver the Niachos Lecture, an honor previously granted to such notables as Alan Greenspan and Larry Summers. Niall had to tell the intelligentsia all about how all the previous history (going back centuries, as is Niall’s style) of indebted nations is somehow going to come back and grab control of the USA in the near future and do something or other very important to it, because he took damned near an hour and a half of their time up with his lecture.

Video, audio, slides, transcript: http://www.iie.com/events/event_detail.cfm?EventID=152

In regards to the second part of your post, you seem to argue that the unexpected rise in initial claims might not be so bad since, in a recovery, people tend to flood the labor market as employment increases. But once an individual drops out of the labor force for a period of time, they are ineligible for unemployment benefits regardless of whether or not they return. Rising initial claims means people are losing their jobs, for you can only claim unemployment if you are laid off.

There is certainly a lot of noise going on with initial claims numbers, so the end story of rising employment might be correct, but I don’t see how increased labor force participation can affect initial claims numbers in any significant way. Am I getting your argument right? Thanks.

DS,

Regaring your post above, and not being from the US or being an economist I can imagine reasons why in theory Bill might be correct.

Given that everything to do with unemployment is a bunch of aggregates of different people in different positions this might account for the picture being confusing.

If for example a person gets laid off, receives welfare for 6 months then stops receiving it as they are no longer entitled, they may then go ‘under-the-radar’ and become regarded as hidden unemployed (even if they are still looking for a job). They might then find that prospects improve and look for a job and get one, ahead of someone who is still receiving welfare, and ahead of someone that is just about to be laid off.

In fact, if you consider high turnover of people losing their jobs and then finding new ones, and, if you then consider that during a recession the chance of finding a new job whilst still eligable for welfare is low, then you might find that most people who find new jobs do so whilst not eligable for welfare. If such people are considered ‘hidden unemployed’ then that might validate Bill’s idea.

I don’t agree that people should stop receiving welfare after a period as in the US, not least because they would be under-the-radar. Better all round for the government to guarantee them a job in fact.

Dear ds

I think you are correct which is why I wrote the qualifier in the original text:

We will not know whether the claimants data is signalling a new overall deterioration until the May labour force data is published in a few weeks.

best wishes

bill

Thanks a lot for the response!

Quotes from two Germans: the first a conservative, and the second (consciously or unconsciously) an MMTer.

1. Wolfgang Schauble, Germany’s finance minister, on deficits “…..Germany must do more for growth. We have a role as a locomotive. But then I must ask: what should we do to grow faster? It cannot be by building up bigger deficits, contrary to the recommendations of the [EU] stability and growth pact. That is crazy. I must reduce my deficit.”

See Financial Times article: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b82f3e3c-6377-11df-a844-00144feab49a.html

2. Claude Hillinger: “An aspect of the crisis discussions that has irritated me the most is the implicit, or explicit claim that there is no alternative to governmental borrowing to finance the deficits incurred for stabilization purposes. It baffles me how such nonsense can be so universally accepted. Of course, there is a much better alternative: to finance the deficits with fresh money.”

See Economics E-Journal discussion paper: http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2010-1/view

Dear Ralph,

I get the impression, from section 4.4 for example, that Hillinger is not an MMTer!

Best regards

Graham

I like this one from Euro Intelligence: “Germany is unfit for the Euro” by Joerg Bibow (http://bit.ly/cul4V5)

Quotation:

“Not for the first time in its history the German people have been irresponsibly misled by a political leadership that seems to have lost any sense of history, any sense of order and stability in Europe, and any sense of Germany’s key contributing role to the current crisis. As ever, the mindset of lawyers frames the political debate among a political class that seems inhumanly uneducated in matters of economics. If economic voices are heard at all, it is usually the voice of the Bundesbank. It is a peculiar democracy that expects either its constitutional court or central bank to have the final word of wisdom.”

Of course PIIGS can fly after eating a free lunch!

Now the eurocrats only have the monetary policy run by unelected unaccountable loonies, got a supreme court that can dictate this and that and plenty other tools to control Europe, but they are not satisfied, they now need unaccountable fiscal and political supremacy to make the Europeans fit in to their Procrustes Bed.

If they is ardent enemies of any sort of fiscal stimulus and their biggest concern is public deficits and think balanced budgets is the remedy for the present situation how can anyone believe that they are going to use fiscal and political supremacy in a wise way. The risk that these powers in the hand of the eurocrats would have made things from bad to worse is immense. Like handing over the lighter to the pyromania.

These eurocrats that didn’t see it coming and when it came they didn’t understand and still don’t get it, now they want to have total supremacy over all the democratically elected bodies in Europe and like Roman emperors make thump up or down on what democratic bodies have decided.

“The German Chancellor during the late Weimar republic, Heinrich Brüning, was the most obsessed by fiscal orthodoxy of all statesmen at the time. His fear of budget deficits made him pursue a policy of merciless austerity, which forced the German unemployment rate up to 40 percent. The increasingly desperate population came to view Hitler as “unsere letzte Hoffnung” – our last hope. A racy detail in this historical misery, is the Keynes met Brüning in Berlin 1932. The Chancellor had to face harsh criticism, but Brüning boldly declared that it would be folly to give up “a hundred yards from the finishing post”. But Brüning never reached the finishing post. Instead, he unrolled the red carpet for Hitler.

The real obstacles to expansion are neither economic nor financial, but political. If the political desire to carry out an expansion is lacking, then surely nothing is going to happen. I nourish but little hope that the present decision-makers will come to their senses. Today, they are marching like a lemming migration towards an economic, social and political precipice. The possession with savings and the obsession with austerity have turned into a national neurosis, based on the hallucinatory notion of the “economically necessary”. The destructive forces are enormously strong. To stand up against the tide and appeal to common sense would most probably only lead to one being trampled down. The lemmings have made up their minds. They don’t know why, but they know where they are going. And they do what is necessary to get there. “ ”

Per Gunnar Berglund – a Swedish economist that moved to USA for some academic freedom in the field of economy on the bizarre budget consolidation in Sweden during the 90s.

@/L Do you have a link to this article from Gunnar Berglund? Thanks a lot.

It is from:

Abolishing unemployment

By Per Gunnar Berglund

Ordfront Publishing House, August 1996

I did have it as pdf but I couldn’t find a link so I put it up tempoarliy at a free account I have on http://www.freei.me/.

http://www.bokeh.freei.me/Abolishing%20unemployment.pdf

I’m sure the copy was free to download when I did it so then I’ll guess it’s free to supply it to others. 🙂

I’ll hope this workout better:

Abolishing_unemployment.pdf

If the upload breaks the link it shall be like this:

http://

hem.bredband.net/

b209626/Abolishing_unemployment.pdf

Thanks for that great link to Abolishing Unemployment, /L.

Section 5 (page 53 onwards) looks like pure MMT. Hope the rest is as good.

Berglund must be a mate of yours Bill !

I smiled wryly at this:

“That is why it is so depressing to hear ministers of the

Cabinet officially announce that “there is no more money”.”

Isn’t that exactly what shadow Finance Minister Andrew Robb said in Canberra last week following the Hockey debacle ?

It is indeed a depressing thought, in every respect. I think I can see Andrew’s problem.

More depressing however is the thought of Robb as a Cabinet Minister.

@/L Many thanks for the link. For sure a good read for a long Pentecost holiday weekend.

” But who cares about the economy today? Every day, programmes like “A-Economy” are and “The Economic Club” are broadcast [Swedish Public Service on “economy”]. But there is no discussion of the economy, only of the finances. Short- and long-term interest rates, budget deficits, equity quotes and whatnot are discussed, but not the economy.

The “economy” is not the same thing as the “finances”. The economy is human activities, the way we create value by using our knowledge and talents. Today’s waste of human resources has no place in the cynical world of finance.

…

The real-world economy must comply to being cut short in order to fit this financial Procrustes’ bed. To Erik Åsbrink’s [Finance Minister] mind, the map is the reality. The length of the columns is beginning to harmonise, which makes Erik Åsbrink “happy”. The whole of the Cabinet is “happy”. The debit and credit of government finances match. …”

Per Gunnar Berglund 1997

“The demand for German military hardware from Greece has allowed the German economy to grow faster than it would without net public spending”.

Um. This statement seems to imply that arms exports from Germany to Greece are pretty significant. If you look at the SIPRI numbers for total arms exports from Germany since 1980 (an arbitrary start date), you get a lot of variability but certainly you get high numbers from about 2003. Whether the numbers are high enough to justify that statement about the German economy growing faster than otherwise is a bit dependent on how much of German/Greek trade is German arms exports to Greece, and how important German/Greek trade is anyway. The SIPRI numbers are adjusted for type of weapon, so you can’t just compare them with total exports or with GDP, somewhat irritatingly.

I also found that German arms exports to Turkey exceed those to Greece over the 1980-2009 period, but are about equal over the 2000-2009 peiod. Greece and Turkey seem to be the major destinations for German arms over the whole period.

http://www.sipri.org/databases

(using the Arms Transfers Database)

Bill,

could you please clarify how you calculated unemployment rate adjusted for changes in participation? I can not arrive at your results and figure out where I have a mistake

thank you

Bill,

sorry, I think I got it by working with raw numbers but would still appreciate your input to confirm my logic.

thank you

Dear Sergei

The following graphic will explain it:

best wishes

bill