Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – May 14, 2011 – answers and discussion

Question 1:

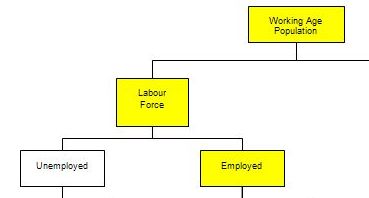

As long as employment growth keeps pace with labour force growth, unemployment will not rise.The answer is False. If you didn’t get this correct then it is likely you lack an understanding of the labour force framework which is used by all national statistical offices. The labour force framework is the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data. The framework is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop the guidelines or norms for implementing the labour force framework and generating the national labour force data. The rules contained within the labour force framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework;

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework; and

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at a specified moment in time.

The Working Age Population (WAP) is usually defined as those persons aged between 15 and 65 years of age or increasing those persons above 15 years of age (recognising that official retirement ages are now being abandoned in many countries).

As you can see from the diagram the WAP is then split into two categories: (a) the Labour Force (LF) and; (b) Not in the Labour Force – and this division is based on activity tests (being in paid employed or actively seeking and being willing to work).

The Labour Force Participation Rate is the percentage of the WAP that are active.

You can also see that the Labour Force is divided into employment and unemployment. Most nations use the standard demarcation rule that if you have worked for one or more hours a week during the survey week you are classified as being employed.

If you are not working but indicate you are actively seeking work and are willing to currently work then you are considered to be unemployed.

If you are not working and indicate either you are not actively seeking work or are not willing to work currently then you are considered to be

Not in the Labour Force.

So you get the category of hidden unemployed who are willing to work but have given up looking because there are no jobs available. The statistician counts them as being outside the labour force even though they would accept a job immediately if offered.

Now trace through the yellow boxes which are linked by the following formulas:

Labour Force = Employment + Unemployment = Labour Force Participation Rate times the Working Age Population

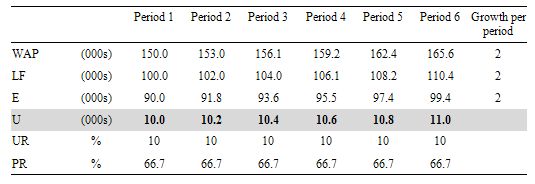

Consider the following Table which shows the Labour Force aggregates for a stylised nation and the WAP, Labour Force and Employment are all growing at a constant rate (in this case 2 per cent).

The Working Age Population (WAP) is usually defined as those persons aged between 15 and 65 years of age or increasing those persons above 15 years of age (recognising that official retirement ages are now being abandoned in many countries).

As you can see from the diagram the WAP is then split into two categories: (a) the Labour Force (LF) and; (b) Not in the Labour Force – and this division is based on activity tests (being in paid employed or actively seeking and being willing to work).

The Labour Force Participation Rate is the percentage of the WAP that are active.

You can also see that the Labour Force is divided into employment and unemployment. Most nations use the standard demarcation rule that if you have worked for one or more hours a week during the survey week you are classified as being employed.

If you are not working but indicate you are actively seeking work and are willing to currently work then you are considered to be unemployed.

If you are not working and indicate either you are not actively seeking work or are not willing to work currently then you are considered to be

Not in the Labour Force.

So you get the category of hidden unemployed who are willing to work but have given up looking because there are no jobs available. The statistician counts them as being outside the labour force even though they would accept a job immediately if offered.

Now trace through the yellow boxes which are linked by the following formulas:

Labour Force = Employment + Unemployment = Labour Force Participation Rate times the Working Age Population

Consider the following Table which shows the Labour Force aggregates for a stylised nation and the WAP, Labour Force and Employment are all growing at a constant rate (in this case 2 per cent).

You observe unemployment rising although the unemployment rate is constant as is the participation rate.

The reason is that the Labour Force is a larger aggregate than Employment because it would be impossible for unemployment to be zero (frictions alone – people moving between jobs – will deliver some small positive unemployment).

So although both the Labour Force and Employment grow at a constant rate, the gap between them (Unemployment) gets larger each period although the proportion of the Labour Force that is unemployed remains constant.

You may wish to read the following blog for more information:

Question 2:

You observe unemployment rising although the unemployment rate is constant as is the participation rate.

The reason is that the Labour Force is a larger aggregate than Employment because it would be impossible for unemployment to be zero (frictions alone – people moving between jobs – will deliver some small positive unemployment).

So although both the Labour Force and Employment grow at a constant rate, the gap between them (Unemployment) gets larger each period although the proportion of the Labour Force that is unemployed remains constant.

You may wish to read the following blog for more information:

Question 2:

When a government issues debt it creates more non-inflationary space for itself to spend than if it spent without issuing debt.The answer is False. The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always). The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations. They claim that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending. All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why. So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt? Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made. The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases. This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target. When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation. There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector. What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector. The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution). There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector. Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply. However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

The non-government sector is wealthier when the government matches it deficit with new debt issues.The answer is False. This answer is complementary to that provided for Question 1 and relies on the same understanding of reserve operations. So within a fiat monetary system we need to understand the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt. That understanding allows us to appreciate what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt? Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made. The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases. This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management as explained in the answer to Question 1. But at this stage, M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. In other words, budget deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector. What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector. The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution). There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector. You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

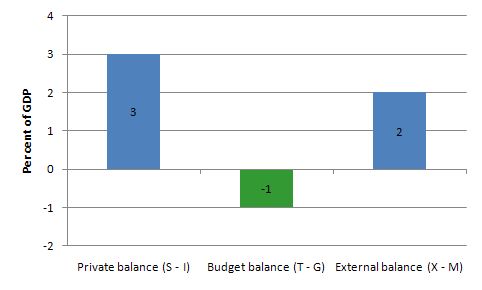

If net exports are running at 2 per cent of GDP, and the private domestic sector overall is saving an equivalent of 3 per cent of GDP, the government must: (a) Be running a surplus equal to 1 per cent of GDP. (b) Be running a surplus equal to 5 per cent of GDP. (c) Be running a deficit equal to 1 per cent of GDP. (d) Be running a deficit equal to 1 per cent of GDP.The answer is Option C Be running a deficit equal to 1 per cent of GDP. This question tests your knowledge of the sectoral balances that are derived from the National Accounts. First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So: (1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M) where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports). Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses: (2) Y = C + S + T where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined). You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write: (3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M) You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get: (4) S + T = I + G + (X – M) Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness. So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external: (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M) The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion. Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. Second, you then have to appreciate the relative sizes of these balances to answer the question correctly. The rule is that the sectoral balances have to sum to zero. So if we write the condition above as: (S – 1) – (G – T) – (X – M) = 0 And substitute the values of the question we get: 3 – (G – T) – 2 = 0 We can solve this for (G – T) as (G – T) = 3 – 2 = 1 Given the construction (G – T) a positive number (1) is a deficit. The outcome is depicted in the following graph.

This tells us that even if the external sector is growing strongly and is in surplus there may still be a need for public deficits. This will occur if the private domestic sector seek to save at a proportion of GDP higher than the external surplus.

The economics of this situation might be something like this. The external surplus would be adding to overall aggregate demand (the injection from exports exceeds the drain from imports). However, if the drain from private sector spending (S > I) is greater than the external injection then the only way output and income can remain constant is if the government is in deficit.

National income adjustments would occur if the private domestic sector tried to push for higher saving overall – income would fall (because overall spending fell) and the government would be pushed into deficit whether it liked it or not via falling revenue and rising welfare payments.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

This tells us that even if the external sector is growing strongly and is in surplus there may still be a need for public deficits. This will occur if the private domestic sector seek to save at a proportion of GDP higher than the external surplus.

The economics of this situation might be something like this. The external surplus would be adding to overall aggregate demand (the injection from exports exceeds the drain from imports). However, if the drain from private sector spending (S > I) is greater than the external injection then the only way output and income can remain constant is if the government is in deficit.

National income adjustments would occur if the private domestic sector tried to push for higher saving overall – income would fall (because overall spending fell) and the government would be pushed into deficit whether it liked it or not via falling revenue and rising welfare payments.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

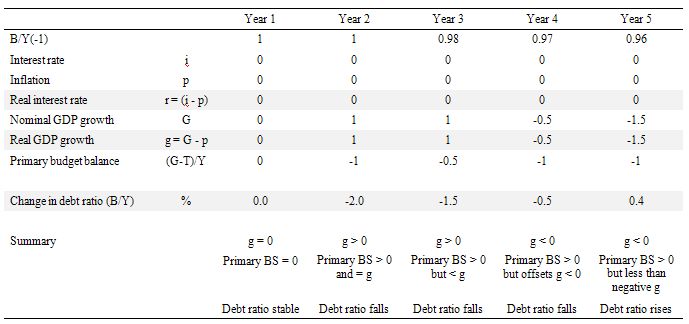

Fiscal austerity programs (which try to create primary budget surpluses) are likely to thwart the chances of a government reducing its public debt as a proportion of GDP because they are likely to reduce real GDP growth which, then drives the budget deficit up via the automatic stabilisers.The answer is False. While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept. The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will always rise when there are deficits. But the rising debt levels do not necessarily have to rise at the same rate as GDP grows. The question is about the debt ratio not the level of debt per se. Rising deficits often are associated with declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend. Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again. It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors. Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”. Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector. Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure. However, in mainstream thinking, the framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

In Year 1, there is zero real GDP growth and the Primary Budget Balance is also zero. Under these circumstances, the debt ratio is stable.

Now in Year 2, the fiscal austerity program begins and assume for the sake of discussion that it doesn’t dent real GDP growth. In reality, a major fiscal contraction is likely to push real GDP growth into the negative (that is, promote a recession). But for the sake of the logic we assume that nominal GDP growth is 1 per cent in Year 2, which means that real GDP growth is also 1 per cent given that all the nominal growth is real (zero inflation).

We assume that the government succeeds in pushing the Primary Budget Surplus to 1 per cent of GDP. This is the mainstream nirvana – the public debt ratio falls by 2 per cent as a consequence.

In Year 3, we see that the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive (0.5 per cent of GDP) but is now below the positive real GDP growth rate. In this case the public debt ratio still falls.

In Year 4, real GDP growth contracts (0.5 per cent) and the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive (1 per cent of GDP). In this case the public debt ratio still falls which makes the proposition in the question false.

So if you have zero real interest rates, then even in a recession, the public debt ratio can still fall and the government run a budget surplus as long as Primary Surplus is greater in absolute value to the negative real GDP growth rate. Of-course, this logic is just arithmetic based on the relationship between the flows and stocks involved. In reality, it would be hard for the government to run a primary surplus under these conditions given the automatic stabilisers would be undermining that aim.

In Year 5, the real GDP growth rate is negative 1.5 per cent and the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive at 1 per cent of GDP. In this case the public debt ratio rises.

The best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio – which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

]]>

In Year 1, there is zero real GDP growth and the Primary Budget Balance is also zero. Under these circumstances, the debt ratio is stable.

Now in Year 2, the fiscal austerity program begins and assume for the sake of discussion that it doesn’t dent real GDP growth. In reality, a major fiscal contraction is likely to push real GDP growth into the negative (that is, promote a recession). But for the sake of the logic we assume that nominal GDP growth is 1 per cent in Year 2, which means that real GDP growth is also 1 per cent given that all the nominal growth is real (zero inflation).

We assume that the government succeeds in pushing the Primary Budget Surplus to 1 per cent of GDP. This is the mainstream nirvana – the public debt ratio falls by 2 per cent as a consequence.

In Year 3, we see that the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive (0.5 per cent of GDP) but is now below the positive real GDP growth rate. In this case the public debt ratio still falls.

In Year 4, real GDP growth contracts (0.5 per cent) and the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive (1 per cent of GDP). In this case the public debt ratio still falls which makes the proposition in the question false.

So if you have zero real interest rates, then even in a recession, the public debt ratio can still fall and the government run a budget surplus as long as Primary Surplus is greater in absolute value to the negative real GDP growth rate. Of-course, this logic is just arithmetic based on the relationship between the flows and stocks involved. In reality, it would be hard for the government to run a primary surplus under these conditions given the automatic stabilisers would be undermining that aim.

In Year 5, the real GDP growth rate is negative 1.5 per cent and the Primary Budget Surplus remains positive at 1 per cent of GDP. In this case the public debt ratio rises.

The best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio – which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

]]>

For Q2, I would like to see what the various accounting would look like on day 366 if the gov’t issued a 365 day bond that both principal and interest were set up to paid off in full on day 365 vs. no bond (mostly equivalent to currency with no bond attached). Thanks!

For Q3, Would’nt the interest paid to the holders of the government debt count as income to the non-governmen sector? By issuing debt for any given amount of spending isnt the amount of that spending increased by whatever interest payments are made? Or is increased income for the non-government sector not the same as wealth?

For question 2, say there’s $100 of cash and deposits in the economy. Now the govt deficit spends $50 and sells $50 in treasury bonds to non-banks. Now there is $100 of cash/deposits and $50 in treasury bonds.

Instead say the govt deficit spends without selling bonds. Well then there is $150 of cash/deposits in the economy.

Why do you think there is no inflationary difference between $100 in cash/deposits and $50 in treasuries vs $150 cash/deposits straight? In the latter, you have an additional $50 that can actually make a purchase. The $50 in treasuries cannot be used to purchase something.

There has to be SOME difference.

Jerry Brown said: “For Q3, Would’nt the interest paid to the holders of the government debt count as income to the non-governmen sector?”

Doesn’t it depend on where the interest is from? Couldn’t it be a loss of income for one non-gov’t sector and an increase of income for another non-gov’t sector?

xyz, let’s expand on that.

Q2, $100 cash and deposits. Apple is saving $25. Microsoft is saving $25. That $50 of medium of exchange has a velocity of 0.

Now the gov’t deficit spends $50 (velocity not 0 with spending not tax cuts) and sells $25 in treasury bonds to each. Now there is $100 of cash/deposits with some velocity and $50 in treasury bonds (savings).

Instead say the govt deficit spends without selling bonds. Well then there is $150 of cash/deposits. But Apple is saving $25, and Microsoft is saving $25. There are $100 of cash/deposits with some velocity and $50 of cash/deposits (medium of exchange savings with a velocity of 0).

Back to the treasury bonds and if they were set up to pay both interest and principal, would the amount of medium of exchange (cash/deposits) remain at $100 when they matured vs. the $150 of cash/deposits the second way (no treasury bond)?

Fed Up, I am not following your last sentence. Maybe you can spell it out more clearly.

Also, why were MSFT and Apple willing to save in Tsys instead of their original investments? And who’s to say they were already saving $50. Maybe they were only saving $25 combined? I understand I am making hypotheticals with no basis, but I am trying to understand why I should be so confident Tsy issuance doesn’t alter the % of savings of the private sector; ie why we can be so confident it’s just a portfolio shift rather than savings/consumption shift.

“And who’s to say they were already saving $50”

There wouldn’t be a $50 government deficit otherwise and therefore no need for $50 of bonds.

That’s the MMT point. The deficit is the outcome of the private sector spending choices. What remains is cash stocked at that point with a velocity of zero. The government then swaps that for a higher interest paying instrument because the policy of the government is to give handouts to people with left over cash.

“There wouldn’t be a $50 government deficit otherwise and therefore no need for $50 of bonds….The deficit is the outcome of the private sector spending choices.”

Can you expound? I have never heard that the govt deficit spends only because people want to save. Govts deficit spend because they have policy goals in mind that are much broader than that.

I have never heard that the govt deficit spends only because people want to save.

If the government doesn’t spend sufficient to offset the non-government sector’s overall decision to ‘net save’ financial assets then the economy will shrink – for the fairly obvious reason that all the output will not be sold in that period (investment increases via the run up in inventory – which is a signal to reduce production).

It is the non-government sector that decides to invest less and to save more. That is deflationary and must be offset by the currency issuer introducing an offset back into the economy via its capacity to spend without funding – or you will likely get a recession. Similarly if you get a boom where people are running down their savings and investment has gone nuts the currency issuer must withdraw funds from the economy to get it to quieten down.

“Back to the treasury bonds and if they were set up to pay both interest and principal, would the amount of medium of exchange (cash/deposits) remain at $100 when they matured vs. the $150 of cash/deposits the second way (no treasury bond)?”

xyz said: “Fed Up, I am not following your last sentence. Maybe you can spell it out more clearly.”

I will try. At the beginning, Apple and Microsoft lost $25 each in medium of exchange. They get one bond each yielding 10% (keep the math easy) for a 1-year term. Someone else gets $50 worth of medium of exchange. At the end of a year, that someone loses $50 of medium of exchange plus $5 interest (assuming interest and principal payments). Microsoft and Apple each get back their $25 of medium of exchange plus $2.50 interest. I’m thinking on day 366 that there is still $100 of medium of exchange, but there is a transfer of $5 in interest. With currency and no bond attached, on day 366 there is $150 of medium of exchange.

The other problem is most of the time the gov’t budget is set up so that only interest payments are made. This introduces rollover risk when the bonds mature. In crisis times, this also allows gov’ts to want to takeover unaffordable private debt to prevent a recession/price deflation becauses not having to pay back both principal and interest makes it seem affordable.

xyz said: “Also, why were MSFT and Apple willing to save in Tsys instead of their original investments?”

because the original investments (currency, demand deposits, checking accounts) yielded 0% to .25%. Maybe the 1-year treasury yields 1%.

And, “And who’s to say they were already saving $50. Maybe they were only saving $25 combined?”

Could be. Then, the gov’t only borrows $25. I picked those companies because they both could be labeled excess savers who don’t retire.

And, “I am trying to understand why I should be so confident Tsy issuance doesn’t alter the % of savings of the private sector; ie why we can be so confident it’s just a portfolio shift rather than savings/consumption shift.”

Can you rephrase that? I’m not getting it on the first reading.

xyz said: “I have never heard that the govt deficit spends only because people want to save.”

Accounting says:

savings of the non-gov’t sector = dissavings of the gov’t sector (usually deficit)

***

While technically true, I believe that is too simplistic. Out in the real world, I see:

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (with most of the dissavings as debt)

***

It also does not distinguish between the possibility of dissaving with currency and no bond attached from dissaving with debt.

XYZ: Why do you think there is no inflationary difference between $100 in cash/deposits and $50 in treasuries vs $150 cash/deposits straight? In the latter, you have an additional $50 that can actually make a purchase. The $50 in treasuries cannot be used to purchase something.

There has to be SOME difference.

There are effects going both ways, they may cancel out, or inflationary effects of printing interest bearing bonds instead of printing zero interest money may even dominate. The treasuries pay interest = more money later = inflation maybe. Raising rates can raise business’s borrowing costs and thus the prices they charge.

Whether bond issuance will actually increase saving and decrease spending is the real, immediate question. The $50 in treasuries can be used to purchase something. They are marketable and can be turned into currency immediately. They can be used as collateral for a loan. But overall, in Abba Lerner’s words – “These effects are not likely to be very great.”

War bonds /savings bonds are government bonds that can behave as some fantasize all bonds always must do, and which may have a real anti-inflationary effect by increasing savings. They are not marketable or usable as collateral and therefore are less “moneyish” than Treasury bonds. The US public held a large amount of these retail bonds, with an attractive rate, during WWII and this had real effect in minimizing wartime inflation by deferring consumption, as did the wholesale low interest Treasury bond rate policy.