Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – May 7, 2011 – answers and discussion

Question 1:

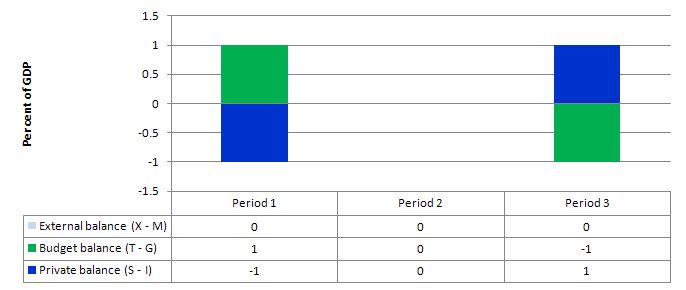

If a nation records an external balance (net exports equal zero) then the government can safely run a balanced public budget without undermining the capacity of the private domestic sector to save overall.The answer is False. This is a question about sectoral balances. Skip the derivation if you are familiar with the framework. First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So: (1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M) where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports). Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses: (2) Y = C + S + T where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined). You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write: (3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M) You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get: (4) S + T = I + G + (X – M) Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness. So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external: (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M) The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion. Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance. Period 1, the budget is in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector. In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save (S – I = 1). Period 2, is the case in point and the sectoral balances show that if the external sector is in balance and the government is able to achieve a fiscal balance, then the private domestic sector must also be in balance. The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable.

So under the conditions of the question, the private domestic sector cannot save. The government would be undermining any desire to save by not providing the fiscal stimulus necessary to increase national output and income so that private households/firms could save.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

So under the conditions of the question, the private domestic sector cannot save. The government would be undermining any desire to save by not providing the fiscal stimulus necessary to increase national output and income so that private households/firms could save.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

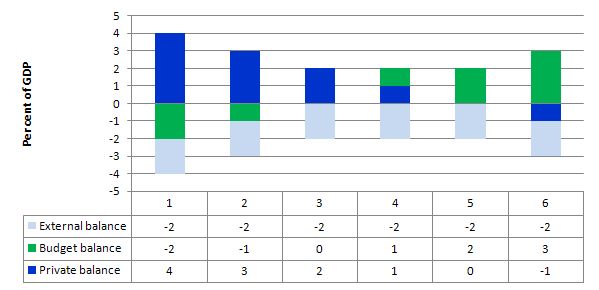

If the external sector is in deficit overall and GDP growth rate is lower than the real interest rate, then: (a) Both the private domestic sector and the government sector overall can pay down their respective debt liabilities. (b) Either the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities. (c) Neither the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities.The answer is (b) Either the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities.. The answer is Option (b) because if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules. It also follows that it doesn’t matter how fast GDP is growing, if a sector is in deficit then it cannot be paying down its nominal debt. To understand this we need to begin with the national accounts which underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics. Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns). State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns). This cannot be a sustainable growth strategy because eventually the private sector will collapse under the weight of its indebtedness and start to save. At that point the fiscal drag from the budget surpluses will reinforce the spending decline and the economy would go into recession. State 2 shows that when the budget surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced. State 3 is a budget balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country. States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the budget goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed budgets into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough budget deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed budgets into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough budget deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

The standard of living of workers falls if growth in real wages fails to keep pace with labour productivity growth.The answer is False. Under the conditions specified there are several things we can conclude:

- Real wages are growing.

- Labour productivity is growing faster.

- The wage share is falling and Real Unit Labour Costs are falling.

- The workers’ material standard of living is higher than if real wages growth was zero or worse.

- That the rise in material living standards are less than would be indicated by the workers contribution to production.

- Wage share = (W.L)/$GDP

- Nominal GDP: $GDP = P.GDP

- Labour productivity: LP = GDP/L

- Real wage: w = W/P

productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers. The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation. Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth. So the wage share has fallen in many nations operating under these conditions. Thus workers could have enjoyed much higher material living standards if they could have claimed more of the productivity growth (and kept the wage share constant). The following blogs may be of further interest to you: Question 4:

Rising private domestic saving overall signals the need for an expanding public deficit to avoid employment losses.The answer is False. The answer also relates to the sectoral balances framework outlined in detail above. When the private domestic sector decides to lift its saving ratio, we normally think of this in terms of households reducing consumption spending. However, it could also be evidenced by a drop in investment spending (building productive capacity). The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process. The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period. Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms layoff workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere. At that point, the economy is heading for a recession. Interestingly, the attempts by households overall to increase their saving ratio may be thwarted because income losses cause loss of saving in aggregate – the is the Paradox of Thrift. While one household can easily increase its saving ratio through discipline, if all households try to do that then they will fail. This is an important statement about why macroeconomics is a separate field of study. Typically, the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur – in the form of an expanding public deficit. The budget position of the government would be heading towards, into or into a larger deficit depending on the starting position as a result of the automatic stabilisers anyway. So an intuitive reasoning suggests that a demand gap opens and the only way to stop the economy from contracting with employment losses if it the government fills the spending gap by expanding net spending (its deficit). However, this would ignore the movements in the third sector – there is also an external sector. It is possible that at the same time that the households are reducing their consumption as an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports). So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough. The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors. The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

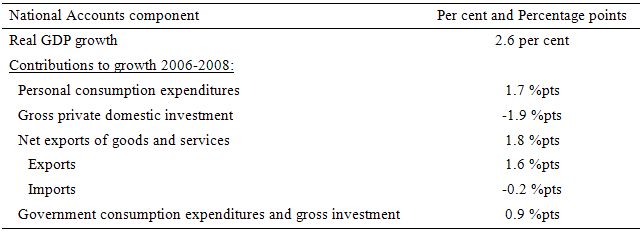

From the US National Accounts, you find that in 2006, the share of Personal consumption expenditure in real GDP was 69.9 per cent and by 2008 it had fallen to 69.8 per cent. Similarly, the share of Gross private domestic investment on real GDP was 17.2 per cent in 2006 and by 2008 had fallen to 14.9 per cent (and further to 11.8 per cent in 2009). The net export deficit over the same period (2006 to 2008) fell from -5.7 per cent of real GDP to -4.9 per cent in 2008. Finally, the share of Government consumption expenditures and gross investment in real GDP rose from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 18.9 per cent in 2008 (and 19.7 per cent in 2009). These relative changes confirm that real GDP was lower in 2008 compared to 2006 because the increase in Government spending and the falling negative contribution of net exports were not sufficient to offset the declining contribution from consumption and investment.The answer is False. The detail in the question relates to expenditure shares in real GDP and clearly does not tell you anything about the growth in GDP. All that you are being told are that the shares are changing over the period 2006 to 2008 in favour of public spending. The shares are given by the following equation:

The point of the question (if any) is to warn you into being careful to clarify the concepts being used before drawing conclusions. Too many people think they know what these terms mean and either mis-use them themselves to reach erroneous conclusions or allow themselves to be fooled by others who are touting erroneous conclusions.

If you are interested in more detail on national accounts then the 5216.0 – Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2000 – is the place to go. Recommended reading if you want to get all the concepts and stock-flow relationships really sorted out. The system is universal and used by all statistical agencies.]]>

The point of the question (if any) is to warn you into being careful to clarify the concepts being used before drawing conclusions. Too many people think they know what these terms mean and either mis-use them themselves to reach erroneous conclusions or allow themselves to be fooled by others who are touting erroneous conclusions.

If you are interested in more detail on national accounts then the 5216.0 – Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2000 – is the place to go. Recommended reading if you want to get all the concepts and stock-flow relationships really sorted out. The system is universal and used by all statistical agencies.]]>

Q2, why is the word overall there at all?

Q5, “The fact you know that over this time that real GDP growth in the US was falling is irrelevant – the question asks whether you can conclude from the information before you.”

And, “Over the period 2006-2008, real GDP grew overall by 2.6 per cent.”

Aren’t those two inconsistent?

Q2, “It also follows that it doesn’t matter how fast GDP is growing, if a sector is in deficit then it cannot be paying down its nominal debt.”

What if real GDP growth is higher than the real interest rate? By that, I mean can financial assets being rising, and if so, how does that matter?

Q1: This may be a small quibble, but maybe I’ll learn something as a recent student of MMT. Why isn’t (1) written as Y=C+I+G+X, because X would seem to be a source? Then (2) would be written as Y=C+S+T+M, because M would represent purchase of foreign merchandise.

Then the (X-M) term drops out naturally or algebraically without putting them together in (1). That is, the X-M term is no more intuitive than the other two terms.

I like your quizzes.

“Typically, the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur – in the form of an expanding public deficit.”

I find it curious how avoiding non-gov sector net saving is never offered up as a policy alternative. Even if all of the dis-saving was limited to the wealthiest 0.1% partially dis-saving (eg; so as to meet an asset tax demand), wouldn’t that be enough to avoid recession?

Off topic:

What does everyone think of this?

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/05/geithner-blocked-imf-deal-to-haircut-irish-debt.html

Title speaks for itself. It also talks about Germany, WWI, and John Maynard Kenyes.

Ok, never mind I got it. My expressions for Y are wrong, because they confuse two different views of GDP.