I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The IMF – incompetent, biased and culpable

On February 11, 2011, the IMF’s independent evaluation unit – Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) – released a report – IMF Performance in the Run-Up to the Financial and Economic Crisis: IMF Surveillance in 2004-07 – which presents a scathing attack on the Washington-based institution. It concluded that the Fund was poorly managed, was full of like-minded ideologues and employed poorly conceived models. In a previous report the IEO had demonstrated how inaccurate the IMF modelling has been. But the IMF is an organisation that goes into the poorest nations and bullies them into harsh policy agendas which the IEO has now found to be based on poor theory and inadequate model implementation. That makes the IMF more than an incompetent and biased organisation. In my view it makes them culpable. Who is going to pay?

The Evaluation Report:

… finds that the IMF provided few clear warnings about the risks and vulnerabilities associated with the impending crisis before its outbreak. The banner message was one of continued optimism … The belief that financial markets were fundamentally sound and that large financial institutions could weather any likely problem lessened the sense of urgency to address risks or to worry about possible severe adverse outcomes. Surveillance also paid insufficient attention to risks of contagion or spillovers from a crisis in advanced economies.

In fact, the IMF ignored the advanced economies altogether in their “Vulnerability Exercise” which they undertook after the 1997 Asian Crisis.

So the message is clear – the IMF were proponents of the “Great Moderation” which was the dominant narrative during the 1990s and later. Mainstream macroeconomists – like John Taylor, Robert Barro, Robert Lucas, Ben Bernanke and all the rest of them all preached that the business cycle was contained if not dead and the only interesting questions were how far governments could go in deregulating their labour and product markets and creating free markets.

It was a arrogance that you would not believe unless you worked, as I do, in the profession. It was a gloating, pack-mentality. Like dogs, the mainstream profession hunted in packs and at conferences aggressively suppressed alternative views. I could share many examples where a speaker who did not share the Washington-Harvard-Chicago consensus was set upon during question time with the sole aim of humiliating them.

Sometimes the gang didn’t even wait until the paper was finished before launching their screeching attacks. I have personal experience of being on the reciving end of this treatment several times in my career. In my case it never humiliated me – I just noted how adults would behave in such a churlish mindless manner and this was a direct (positive) function of how mindless their theoretical and applied understanding of the monetary system was.

What reason did the Evaluation Report give for the IMF incompetence?:

The IMF’s ability to correctly identify the mounting risks was hindered by a high degree of groupthink, intellectual capture, a general mindset that a major financial crisis in large advanced economies was unlikely, and inadequate analytical approaches. Weak internal governance, lack of incentives to work across units and raise contrarian views, and a review process that did not “connect the dots” or ensure follow-up also played an important role, while political constraints may have also had some impact.

The IMF is an ideological church of the mainstream macroeconomics. The staffing

In Chapter 5, the Evaluation Report turns to “toward more effective IMF surveillance” and concludes that the IMF:

… needs to (i) create an environment that encourages candor and considers dissenting views; (ii) modify incentives to “speak truth to power;” (iii) better integrate macroeconomic and financial sector issues; (iv) overcome the silo mentality and insular culture; and (v) deliver a clear, consistent message on the global outlook and risks.

The Evaluation Report criticises the “governance” of the IMF at the senior levels for creating what I would term to be a yes-sir-how-high-do-you-want-me-to-jump culture. When often the correct response is to ask why the hell should I jump, IMF staff have no “incentives … to deliver candid assessments” to their managers who operate “silos and ‘fiefdoms'”.

The IMF has had a flawed policy of recruitment into the more senior positions. It hires economists from mainstream backgrounds with doctorates – so you can be sure they have a very narrow (and flawed) conception of the way the macroeconomy works. Most of them will be very capable in a technical sense, which is important.

But if you are a good econometrician but you keep asking the wrong questions for enquiry then you will just produce GIGO (garbage-in/garbage-out).

Please read my blogs – GIGO … and OECD – GIGO Part 2 – for more discussion on this point.

It is clear the IMF could have only seen the crisis coming if it had have diversified its staffing.

In this regard, I found the response of the Evaluation Report to be unsound. They recommended that the IMF should:

– Actively seek alternative or dissenting views by involving eminent outside analysts on a regular basis in Board and/or Management discussions …

– Change the insular culture of the IMF through broadening the professional diversity of the staff, in particular by hiring more financial sector experts, analysts with financial markets experience, and economists with policy-making backgrounds.

First, who would the IMF consider to be eminent outside analysts? They will end up going to Harvard or wherever and hiring more mainstream hacks as well-paid advisors. No solution to be found there.

The point is that the mainstream macroeconomists in the academy, the central banks and the treasuries all failed to understand the unsustainable dynamics that their neo-liberal policy frameworks were generating. They were all part of the club whose memberships extended beyond the front door of 700 19th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20431.

Second, the majority of the financial sector experts and economists with policy-making backgrounds are all tarred with the same brush. This is not solution at all.

These recommendations will just introduce another layer of well-paid orthodox consultants and will do very little to diversify the views of the organisation or dis-abuse the top management of their willful ignorance when it comes to the way the macroeconomic system works.

In 2004, the IEO released a Report which examined the accuracy of the IMF Projections in relation to “Macroeconomic Adjustment in IMF-Supported Programs” for “175 programs approved in the period 1993-2001”. In the evaluation they wrote:

We find that the “model” revealed by IMF staff’s projections differs significantly from the model evident in historical data …

If you read that Report you will learn how the IMF systematically and grossly overestimated fiscal surpluses that would result from imposing their austerity programs. They also systematically and grossly overestimated the current account surpluses that would result.

The evaluation attempted to decompose the source of these large errors. Signficantly, they said that the “IMF staff was apparently working with quite different information about the initial conditions of the program countries than is currently accepted as historical”. It has often been said that the IMF “fly in for a weekend”, hole up in some Treasury office or swish hotel where nothing real about the country can be seen, then fly back to Washington as experts of that nation and impose their programs accordingly.

The evaluation also concluded that “the IMF staff did appear to have a different model in mind when making its projections” both in understanding the macroeconomic adjustment processes and their timing. That is, the real world doesn’t resemble the orthodox macroeconomic models that the IMF use.

Importantly the evaluation concluded that the “difference between projected and historical implementation of policy adjustment” helps explain the forecast errors and that this could be due to “shocks that worsened performance of these aggregates even when conditions were fulfilled”. That is, that the IMF said that things would be fine and they turned out not to be fine because the macroeconomic theories the IMF uses are deeply flawed.

In conclusion, the evaluation said that:

… there is ample evidence that IMF projections, as with other macroeconomic projections, are quite inaccurate.

Since that time the world has become mired in a global financial crisis which morphed very quickly into a near economic depression because governments failed to respond adequately and sequester their real economies from the GFC, which would have been a relatively easier task than what they faced once production fell and unemployment rose.

Anyway, in the current Evaluation Report, there are some classic comparisons with what the IMF was saying at the time and what happened. For example, in relation to Iceland the Report says.

In spite of a banking sector that had grown from about 100 percent of GDP in 2003 to almost 1,000 percent of GDP, financial sector issues were not the focal point of the 2007 Article IV discussions. The massive size of the banking sector was noted, but this was not highlighted as a key vulnerability that needed to be addressed urgently. Instead, the IMF worried about the possibility of overheating, and the staff report was sanguine about Iceland’s overall prospects. For example, the headline sentences in the staff appraisal were “Iceland’s medium term prospects remain enviable. Open and flexible markets, sound institutions … have enabled Iceland to benefit from the opportunities afforded by globalization.” The report presented a positive picture of the banking sector itself, noting that “the banking sector appears well-placed to withstand significant credit and market shocks” and “[B]anks took important steps over the past year to reduce vulnerabilities and increase resilience.”

I just laughed when I read that. Poor Iceland – ravaged by neo-liberalism. Although if you have been following Iceland you will note that it is bouncing back principally because they declined to bail out the banks in say the way Ireland has.

But the point is that the IMF was captured by the mainstream macroeconomics obsession with inflation – note the reference to the only worry the Fund had in the case of Iceland was the “the possibility of overheating”. The whole profession became obsessed with inflation and abandoned any concern for unemployment.

The world-wide neo-liberal resurgence came in the mid-1970s as governments around the world reacted poorly to the OPEC oil shocks. The contractionary policies designed to quell inflation caused a surge in unemployment and the economic dislocation that followed provoked a paradigm shift in macroeconomics. The overriding priority of macroeconomic policy shifted towards keeping inflation low and eschewed the use of active fiscal policy. Concerted political campaigns by neo-liberal governments, aided and abetted by a capitalist class intent on regaining total control of workplaces, hectored communities into accepting that mass unemployment and rising underemployment was no longer the responsibility of government.

As a consequence, the insights gained from the writings of Keynes and others into how deficient demand in macroeconomic systems constrains employment opportunities and forces some individuals into involuntary unemployment were discarded. Mass unemployment was no longer constructed as a systemic failure (deficient aggregate spending). Policy makers progressively adopted Milton Friedman’s conception of the natural rate of unemployment which redefined full employment in terms of a unique unemployment rate (the NAIRU) where inflation is stable. The NAIRU is allegedly determined by supply forces and is invariant to Keynesian demand-side policies.

The resurgence thus alleged that free markets guarantee full employment (that is, Say’s Law which was discredited in the 1930s) and claimed that Keynesian attempts to drive unemployment below the NAIRU would be self-defeating and inflationary.

The NAIRU approach alleges that individuals “choose” unemployment by not searching effectively for available jobs, by failing to develop appropriate skills, by having poor work attitudes (that is, being plain lazy), and by being overly selective in terms of jobs they would accept.

Governments reinforce this individual lethargy by providing income support payments and imposing restrictive regulations on hiring and firing.

Neo-liberals claim the role of government should be restricted to ensuring individuals are “employable” which involves making it harder to access income support payments by imposing pernicious compliance programs; reducing or eliminating other “barriers” to employment (for example, unfair dismissal regulations); and forcing unemployed individuals into training programs to redress deficiencies in their skills and character.

As the neo-liberal ideology became entrenched in the policy making domains of government, advocacy for the use of discretionary fiscal and monetary policy to stabilise the economy diminished, and then vanished. The rhetoric was not new and had previously driven the failed policy initiatives during the Great Depression.

However, history is conveniently forgotten and Friedman’s natural rate hypothesis seemed to provide economists with an explanation for high inflation and alleged three main and highly visible culprits – the use of government deficits to stimulate the economy; the widespread income support mechanisms operating under the guise of the Welfare State; and the excessive power of the trade unions which had supposedly been nurtured by the years of full employment.

All were considered to be linked and anathema to the conditions that would deliver optimal outcomes as prescribed in the neoclassical economics textbooks. With support from business and an uncritical media, the paradigm shift in the academy permeated the policy circles. After the policy commitment to full employment was jettisoned, unemployment accelerated and has never returned to the low levels that were the hallmark of the Keynesian period.

It was alleged that governments could only achieve better outcomes (higher productivity, lower unemployment) through microeconomic reforms. As a result, governments began cutting expenditures on public sector employment and social programs; culled the public capacity to offer apprenticeships and training programs, and set about dismantling what they claimed to be supply impediments (such as labour regulations, minimum wages, social security payments and the like). Privatisation and outsourcing accompanied these policy shifts.

The agenda was clear – reduce government protection of the weak and transfer power to employers by undermining the capacities of trade unions to bargain for advantage.

That the NAIRU approach seduced governments at all is more difficult to understand given the fact that since 1975 there have never been enough jobs available to match the willing labour supply in most nations. It was absurd to base income support payments on relentless job search when there were not enough jobs to go around.

It was inefficient to force the unemployed to engage in on-going training divorced of a paid-work context. But all that was lost on these ideologically-obsessed governments and their policy advisors. The flawed doctrine of full employability mainly functioned to subsidise the needs of private capital by suppressing wages and conditions and creating desperation among the unemployed.

There were also substantial changes in the conduct of macroeconomic policy. Neo-liberals rejected the notion that demand deficiencies can occur. They also were successful in making inflation appear to be a worse problem than unemployment despite the massive income losses and related social costs associated with the latter.

The political importance of inflation has been blown out of all proportion to its economic significance. Whereas unemployment was previously considered one of the more important policy targets, under the neo-liberal paradigm it became one of the powerful policy tools to discipline worker wage ambitions, redistribute national income towards profits and keep inflation at bay.

This is the sort of framework that the IMF championed both within its dealings with the advanced nations but also in the way it imposed harsh adjustment programs on developing countries who sought funds.

The Evaluation Report comments on the ideological biases at the IMF – which they call “Groupthink” (“the tendency among homogeneous, cohesive groups to consider issues only within a certain paradigm and not challenge its basic premises”). They said:

The prevailing view among IMF staff-a cohesive group of macroeconomists-was that market discipline and self-regulation would be sufficient to stave off serious problems in financial institutions. They also believed that crises were unlikely to happen in advanced economies, where “sophisticated” financial markets could thrive safely with minimal regulation of a large and growing portion of the financial system.

But the Evaluation Report doesn’t drill into this very much. It fails to conclude that the models that the mainstream macroeconomists use are flawed if not fraudulent. The closet it gets to this inference is when it says that “IMF economists tended to hold in highest regard” models proven to be inadequate (dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models).

DSGE models are useless for analysing anything of importance in a modern monetary economy. Their construction has absorbed countless person-hours – a major productivity loss for the respective institutions and nations as a whole. My profession is obsessed with these useless artefacts.

The Evaluation Report should have said the IMF should scrap the use of these models. Instead it congratulates the IMF for on-ongoing work “to develop models that can incorporate financial frictions”. Note the term friction – that is very telling.

In the mainstream way of thinking – the underlying truth is the frictionless, perfectly competitive model. Then us humans come along and impose frictions on the model which in the long-run evaporate (according to the way these models are devised and taught). So trade unions are not an intrinsic institution of capitalism to redress the power imbalance between the owners of capital and the workers who must work to eat. They are considered to be an emphemeral nuisance that can be legislated away.

Similarly government itself is a friction on the perfect world and it should legislate itself away as far as is possible – bar defend private property (that is, make sure there is a legal basis for profits).

So in this statement I see the Evaluation Report missing the point entirely. That is no surprise given the Director of the IEO is a mainstream monetary theorist himself.

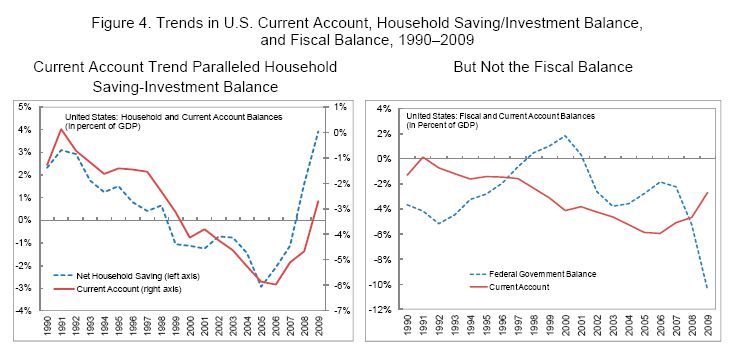

I found the analysis of sectoral flows to be very interesting and also telling. The analysis is only a partial The Evaluation Report presented this Graph (Figure 4) which shows the relationship between net household saving and the current account balance (left-panel) and the budget deficit and the current account balance (right-panel).

The Evaluation Report says that IMF was chiefly concerned “about the risks stemming from the large and growing current account deficit”. Mainstream theory believes (the flawed Twin-deficits theory) that the current account and the budget deficit move together. Despite the Twin Deficits notion not holding empirical water it is still used relentlessly by the mainstream to justify their argument for fiscal austerity.

Please read these blogs – Do current account deficits matter? and Twin deficits – another mainstream myth – for a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective.

The Evaluation Reports says that the IMF discussions:

… repeatedly stressed the need for fiscal consolidation to reduce the current account deficit.

And as the graph shows – they were wrong … as usual.

I found it curious (and biased) that the Evaluation Report did not show the relationship between the budget deficit and household saving. If you mentally construct a third-panel on the graph you will find the familiar result that budget deficits are associated with rising private saving.

This is because net public spending (deficits) promotes rising income levels via its impact on aggregate demand (spending) and allows households to realise their saving desires. Budget surpluses undermine aggregate demand and place a drag on overall income generation making it harder for the economy to grow and providing less capacity for private households to save.

The era of tight fiscal policy that most advanced nation governments pursued (more or less) over the neo-liberal period to provide passive support for the obsession with inflation targetting was associated with economic growth largely driven by rising private sector indebtedness. That dynamic was always unsustainable and led to the GFC.

Please read my blog – Deficits are our saving – for more discussion on this point.

All the Evaluation Report can say about this is that:

Despite this finding, policies to address the household saving-investment imbalance received little attention, as did the question of what role monetary policy might have played in the credit and housing prices booms.

Yes, the IMF was always arguing against budget deficits and so with external sectors typically in deficit, nations could only grow under these circumstances by the private sector indulging in an on-going credit binge – GFC here we come.

The IMF did not only fail to see the crisis coming. They forced policies on nations and pressured governments everywhere to introduce policies which directly contributed to the crisis. The Evaluation Report fails to identify that.

While they conclude the IMF is a poorly governed, ideologically obsessed organisation with deficient modelling capacity, they should have said the Fund was culpable and its senior management should have been made to pay.

Conclusion

The IMF stopped having a purpose in 1971 when the Bretton Woods arrangements were scrapped. The IMF should have been scrapped at the same time.

It should still be scrapped. It serves no useful purpose and has destroyed societies and communities as a result of its flawed applications and harsh adjustment programs.

For more of my analysis of the IMF, please read my blogs:

- The IMF fall into a loanable funds black hole … again

- IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries

- We are sorry

- There are riots in the street but the IMF wants more unemployment

- Ex-IMF official still lost in the incredulous void

- The IMF continue to demonstrate their failings

- There is no positive role for the IMF in its current guise

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back tomorrow some time.

That is enough for today!

Great post, as always.

Exactly. If they had a strong argument, they would use it. Since they don’t, they descend into denial, bullying, sometimes even blind rage.

It can be irritating watching the way the orthodoxy finally gets around to including a heterodox idea here or there in its theory while simultaneously claiming they have understood it all along. But one thing they can’t change is that they had no idea the crisis was coming while others (especially those using the sectoral-balances approach, including MMT economists) did and were explaining the consequences of austerity and the corresponding accumulation of private debt for ten years. The record is there for anyone who wishes to see it in a trail of academic papers.

Btw, Rob Parenteau’s Levy Brief # 88 “U.S. Household Deficit Spending: A Rendezvous with Reality” quoted in the article.

I’m keen to understand the motivation behind the mistakes the IMF made. Do they genuinely believe that they have the accurate view of how things work and repress dissent because they believe the dissenting views are mistaken and dangerous? I was shocked to read that Harvard had paid the US gov in an out of court settlement to cover a charge that the Harvard economists had willfully acted against Russian and US interests in advising on the corrupted privatisations after the Soviet system was wound down. The charge was that the Harvard economists had personally enriched themselves in the corrupt privatisations.

The IMF sounds just like almost all large bureaucratic organizations. Australian government departments are pretty much the same. The solution (if they really want one) is to have opposing teams – one to put forward the mainstream view, the other to be the “devil’s advocates” or “black hats”. The latter should be regarded as just as valuable to the organization and their input to have equal weighting. Of course, it never happens. The only organizations where it does happen are those where profits depend on it, or where there are severe consequences (to the organization) from failure and it is going to be clear when failure happens. This is certainly never the case with international organizations, which are essentially answerable to no-one and are headed by unelected bureaucrats, often international careerist bureaucrats.

If I recall correctly, Henry Hazlett wrote articles critical of the IMF along similar lines in about 1949.

Re Stone’s query,

I recommend that you check Michael Hudson’s site and read his book ‘Super-Imperialism’. Also, check Michael’s brief biographical sketch and ideas on economics at the following link:

http://michael-hudson.com/2002/04/i-meet-the-leading-authority-on-the-babylonian-and-near-east-tradition-of-debt-cancellation/

I have been looking around his newly revised web site, but have not yet found the references he provided on his older site regarding his meetings in the early 1990s with key Russian economists and the related stories about the Harvard economists who ripped off the Russian government by colluding with former KGB members who became the kleptocrats who exploited all of Russian natural resources. It is an interesting story and bears on the subject you mention. Michael has also been involved with people in both Latvia and Iceland with respect to their efforts to try to deal with recent economic disasters.

Bill ~ From naked capitalism. You might be interested:

Deep T: Australian Banking System on Unstoppable Path to Collapse or Government Bailout

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/02/deep-t-australian-banking-system-on-unstoppable-path-to-collapse-or-government-bailout.html

Stone, In the case of the U.K. it looks like Gordon Brown’s government was putting pressure on the IMF to keep quite about the dodgy state of U.K. banks prior to the credit crunch. See:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ad194f30-3548-11e0-aa6c-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1De1xd0ZO

I disagree with Bill on this issue. The IMF is an evil institution so far but at least it put in place an independent evaluation office which is obviously candid enough to expose the evil doings of the fund. This is an extra-ordinary step compared to an age-old institution called university which devolved in a propaganda department in regard to economics. For these “scholars” anything put in place to evaluate their ex cathedra revelations about economics in the light of empirical facts is an insult and endangers academic freedom.

I’ve always liked the late Jonathan Kwitny’s description, in his Endless Enemies, of the IMF (& World Bank) as the international loan-sharking institutions – although the comparison is rather unkind to the Mafia.

“I recommend that you check Michael Hudson’s site and read his book ‘Super-Imperialism'”

M.H. book is available online at: http://www.soilandhealth.org/03sov/0303critic/030317hudson/superimperialism.pdf

While it is true that the IMF is harsh, its role during this crisis has increased. It is the international lender of the last resort. It will have a critical role if for example, its decided that the Euro Zone arrangement has to be abandoned.

This is what happens if some zealots at the IMF and ECB take over your country. Higher education is an unnecessary expense and must be avoided.

http://www.gopetition.com/petition/42790.html

Ramanan: Nicely spotted re: the Rob Parenteau reference. Thanks.

Another interesting review of the performance report:

At the shrink’s bed: The IMF, the global crisis and the Independent Evaluation Office report

Biagio Bossone,Chairman, Group of Lecce, 11 February 2011

http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/6099

‘But the point is that the IMF was captured by the mainstream macroeconomics obsession with inflation – note the reference to the only worry the Fund had in the case of Iceland was the “the possibility of overheating”. The whole profession became obsessed with inflation and abandoned any concern for unemployment.’

This is not a coincidence, the finance sector is hurt badly by inflation. My wage increases have inflation factored into them, I can assume that my wages will keep pace at least with rising prices so inflation doesn’t hurt me or most workers much. But my mortgage doesn’t go up with inflation, in fact, relative to wages and prices my debts go down with inflation. So for me the more inflation the better (up to a point), keep it coming. Even better a lot of the inflationary policies they are so afraid of lower unemployment, even better for me.

But for the rich and for banks inflation is a disaster. Guess who’s interests politicians and economists and the IMF watch out for.