The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The IMF continue to demonstrate their failings

On the first day of Spring, when the sun shines and the flowers bloom, the IMF decide to poison the world with some more ideological positioning masquerading as economic analysis. I refer to their latest Staff Position Note (SPN/10/11) which carries the title – Fiscal Space. I think after reading it the authors might usefully be awarded an all expenses trip to outer space. It is one of those papers that has regressions, graphs, diagrams and all the usual trappings of authority. But at its core is a blindness to the way the world they are modelling actually works. I guess the authors get plaudits in the IMF tea rooms and get to give some conference papers based on the work. But in putting this sort of tripe out into the real policy world the IMF is once again giving ammunition to those who actively seek to blight government intervention aimed at improving the lives of the disadvantaged. The IMF know that their papers will be picked up by impressionable journalists who are too lazy to actually seek a deeper understanding of the way the monetary system operates but happily spread the myths to their readers.

So already today I read a report in the Sydney Morning Herald (September 2, 2010) – Australia well-placed to handle any shocks: IMF – which claims that upon the basis of the IMF paper that:

Australia is among only a handful of major economies where the government’s budget is best placed to deal with “unexpected shocks”, an International Monetary Fund (IMF) report says …

In an analysis of 23 advanced economies, the Washington-based institution examined a country’s “debt limit” based on its historical track record and its current debt level, which it describes as the “fiscal space”.

“Among the advanced economies, Australia, Denmark, Korea, New Zealand and Norway generally have the most fiscal space to deal with unexpected shocks,” the report says.

But it said these countries must be mindful of future fiscal pressures.

In contrast, Greece, Italy, Japan and Portugal have the least fiscal space, while Iceland, Ireland, Spain, the UK and US are also restrained in their degree of “fiscal manoeuver”, it said.

“An absence of fiscal space should not be taken to mean that some form of fiscal ‘crisis’ is imminent, or even likely, but it does underscore the need for credible adjustment plans,” the IMF said.

The AAP story was published by the SMH at 6.50 this morning so they didn’t waste any time getting in spreading the lies.

I particularly liked the last sentence in the above quote. The IMF claimed that nations had run out of fiscal space but that didn’t mean that a crisis was about to occur. They know damn well that there will never be a crisis of solvency for governments such as Japan, the UK and the US.

The SMH report writer didn’t have the acumen to also point out that the comparison between countries that run sovereign monetary systems and countries that are within the Eurozone and have abandoned their sovereignty as a result is invalid at the most elemental level.

Whether the IMF authors appreciate the difference is another matter. I suspect they do not and have just come through graduate training via a mainstream economics program that fails to provide students with the capacity to actually understand how real world monetary systems operate and the crucial differences that exist between say the EMU and the arrangements that exist in say the US or Japan.

But the point is that the press uncritically pass this nonsense on to the unsuspecting public and to policy makers within government. It wouldn’t matter if there wasn’t a lot at stake.

To appreciate what is at stake we just need to think about our Celtic brothers and sisters who are now into their 20th odd month of austerity and the latest data suggests things are getting worse there rather than better. That should come as no surprise but it does provide further real world evidence that should be used in show trials for notable austerians who should be charged with crimes against humanity.

Here is an interesting Bloomberg report – Austerity Hawks Lose Their Celtic Poster Child – that briefly analyses the latest situation in Ireland. I have also been monitoring events there and will probably write a more detailed statistical analysis of what is happening in the coming days.

Last year I gave a presentation at a UNDP meeting in the US and I recorded my thoughts on the audience reaction and my reactions to other papers presented at the meeting in this blog – Bad luck if you are poor!.

While the main focus of the UNDP workshop was employment guarantees (which is something to be happy about), there was still a lot of talk about fiscal space. Any of the presentations that dealt with macroeconomics (other than my contribution and the contribution of fellow MMT traveller Jan Kregel) introduced the concept of fiscal space as if it mattered.

The UNDP appeared to be obsessed with the concept and it conditions the way they think about macroeconomics and constrains the way they construct their economic development assistance agenda. I formed the conclusion that the constraints that this erroneous thinking places on their policy vision goes a long way to explaining why there has been no significant increase in standards of living in the poorest nations.

Countries will never be able to create the requisite number of jobs necessary to fully employ the available labour while they are being advised by “experts” who operate in the mainstream macroeconomic paradigm.

It is clear that the UNDP constructs its development objectives (including job creation) within a macroeconomic context – see Making fiscal policy working for the poor, which is a UNDP publication published in 2004 and that their blighted notions of fiscal space condition their approach to development.

The IMF defines fiscal space as:

… room in a government´s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy. The idea is that fiscal space must exist or be created if extra resources are to be made available for worthwhile government spending. A government can create fiscal space by raising taxes, securing outside grants, cutting lower priority expenditure, borrowing resources (from citizens or foreign lenders), or borrowing from the banking system (and thereby expanding the money supply). But it must do this without compromising macroeconomic stability and fiscal sustainability – making sure that it has the capacity in the short term and the longer term to finance its desired expenditure programs as well as to service its debt.

You might also like to read this March 2005 IMF paper – Understanding Fiscal Space.

The UNDP has a special WWW Page devoted to fiscal space. This document – Primer: Fiscal Space for the MDGs – is particularly interesting as it juxtaposes the IMF approach with the approach taken by the UNDP. Perceptive readers will realise quickly that at the heart of the matter there is not much difference at all between the two. So the “higher moral ground” that the UNDP attempts to claim is illusory.

The UNDP definition (taken from their Primer) of fiscal space:

… is the financing that is available to government as a result of concrete policy actions for enhancing resource mobilization, and the reforms necessary to secure the enabling governance, institutional and economic environment for these policy actions to be effective, for a specified set of development objectives.

Spot the identical starting point. They both assume that the government has the same constraints that restricted governments during the gold standard when currencies were convertible and exchange rates were fixed. These definitions, despite their subtle differences, could have been written in 1950.

In a fiat monetary system, these concepts of fiscal space are seriously deficient and completely ignore the main points which are:

- a sovereign government is not revenue-constrained which means that fiscal space cannot be defined in financial terms.

- the capacity of the sovereign goverment to mobilise resources depends only on the real resources available to the nation.

At the meeting last year, I was astounded that the UNDP officials seemed to oblivious to these fundamental points. I can accept that many nations struggle with currency sovereignty. Those that have ceded their sovereignty by entering currency zones; by dollarising their currencies; by running currency boards; and similar arrangements clearly are not sovereign and face the same constraints that a country suffered during the gold standard era.

My advice to them would be to implement a plan to remove themselves from these arrangements as quickly as possible. The responsible conduct of the IMF and other agencies would be to help them achieve currency sovereignty as soon as possible.

I also accept that the Eurozone nations are not sovereign and so there are financial dimensions to how we might define the fiscal space their governments enjoy.

But there are hundreds of advanced and developing countries that do have currency sovereignty which means they can enforce tax liabilities in the currency that the government issues. It doesn’t matter if other currencies are also in use in those countries, which is common in many developing nations. For example, the USD will often be in use in a LDC alongside the local currency and be preferred by residents in their trading activities. But, typically, the residents still have to get local currency to pay their taxes. That means the government of issue has the capacity to spend in that currency.

So the point is that as long as there are real resources available for use in a country, the government can purchase them using its currency power.

The current data shows their are millions of people across the “sovereign” world who are unemployed. They represent real resources which have no “market demand” for their services. The government in each country could easily purchase these services with the local currency without placing pressure on labour costs in the country.

So that is background for the latest IMF attempt to comment on how much fiscal space governments currently have.

The current IMF paper claims:

A key issue confronting the global economy today concerns the degree to which countries have room for fiscal maneuver – fiscal space – and, relatedly, the extent to which adjustments in fiscal policies are necessary to achieve/maintain debt sustainability. Financial markets have brought fiscal concerns to the front pages, and a more general reassessment of sovereign risk across a number of countries – given the fiscal legacy of the global financial crisis and looming demographic pressures – remains a palpable threat to the global recovery.

The key issues confronting the global economy are not these at all. For sovereign countries like Australia, the US, Japan, the UK etc if the politicians are spending time addressing non-issues such as these then they are failing in their leadership function.

The key issues are all real – persistent and devastatingly high unemployment; poverty; social dislocation; mental illness; child abuse; environmental degradation and the like.

Further, much of the shift in budget positions across the world has been driven by the automatic stabilisers which will reverse when growth returns. The authors are oblivious to the fact that the only thing that has supported the tepid growth we have seen in the last 12 months has been fiscal policy.

The underlying theme of the paper is that the financial markets don’t like deficits so they will undermine (in some way? how?) future growth. They fail to recognise that the deficits are providing sovereign bonds to the markets who cannot get enough of the paper and bond yields and long-term interest rates generally are falling not rising.

After nearly 2 years of crisis and rising debt ratios, when are the financial markets going to attack the US or Japan? Answer: not in our lifetime.

You also see that the IMF is perpetuating the myth that changing demographics somehow alter the capacity of a sovereign government to credit a bank account. It is just asserted that if there are increased demand for public health that the government will not be able to afford to provide it.

Yes, if there is a shortage of titanium for replacement hips and knees then the government will not be able to purchase the appropriate health care. But as long as there are real resources available for sale in the currency of issue then that government will be able to “afford” them. Whether it wants to buy the goods and services will be a political question. It certainly will never be a financial issue.

So from the outset, the premise of the IMF paper is deeply flawed and warrants the paper being scrapped and the research officers released for sub-standard economic analysis. If that occurred then the whole IMF staff would be unemployed. I don’t support that because I hate unemployment. But I do support re-training for obsolete skills or low-skills and I would recommend that happen. Concerned readers please write to the IMF and urge them to retrain their low skill economics staff (the entire workforce) starting with Blanchard at the top.

The footnote to this opening IMF paragraph said that “(b)y fiscal space, we mean the scope for further increases in public debt without undermining sustainability” – so they are maintaining their earlier definition noted above.

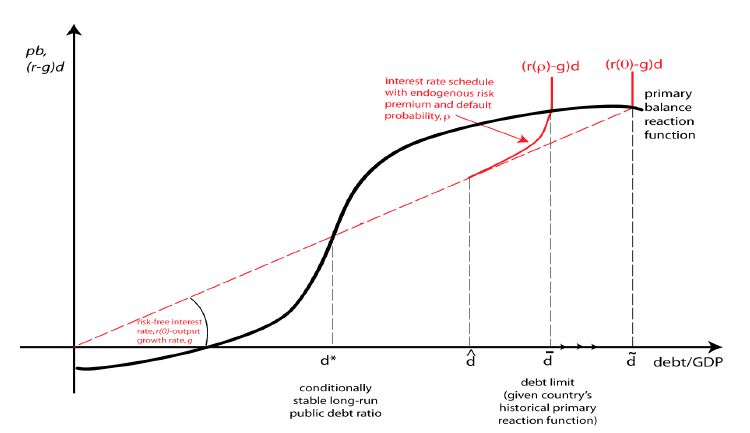

The paper introduces a framework which is summarised by their Figure 1 (reproduced as follows).

They say:

… the solid line is a stylized representation of the behavior of the primary balance as a function of debt. At very low levels of debt, there is little response of the primary balance to rising debt. As debt increases, the balance responds more vigorously, but eventually the adjustment effort peters out as it becomes increasingly more difficult to raise taxes or cut primary expenditures further. The other line represents the effective interest rate schedule, given by the interest rate-output growth rate differential multiplied by the debt ratio. At low levels of debt, the interest rate is the risk-free rate and, assuming that output growth is independent of the level of public debt or the interest rate, this schedule is simply a straight line with slope given by the risk-free interest rate-growth rate differential.

The IMF is employing the standard mainstream macroeconomics textbook analogy between the household and the sovereign government whereby it is asserted that the microeconomic constraints that are imposed on individual or household choices apply equally without qualification to the government. The framework for analysing these choices has been called the government budget constraint (GBC) in the literature.

The GBC is in fact an accounting statement relating government spending and taxation to stocks of debt and high powered money. However, the accounting character is downplayed and instead it is presented by mainstream economists as an a priori financial constraint that has to be obeyed. So immediately they shift, without explanation, from an ex post sum that has to be true because it is an accounting identity, to an alleged behavioural constraint on government action.

The GBC is always true ex post but never represents an a priori financial constraint for a sovereign government running a flexible-exchange rate non-convertible currency. That is, the parity between its currency and other currencies floats and the the government does not guarantee to convert the unit of account (the currency) into anything else of value (like gold or silver).

This literature emerged in the 1960s during a period when the neo-classical microeconomists were trying to gain control of the macroeconomic policy agenda by undermining the theoretical validity of the, then, dominant Keynesian macroeconomics.

Within this model, taxes are conceived as providing the funds to the government to allow it to spend. Further, this approach asserts that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts then has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and (b) by printing money.

You can see that the approach is a gold standard/convertible currency approach where the quantity of “money” in circulation is proportional (via a fixed exchange price) to the stock of gold that a nation holds at any point in time. So if the government wants to spend more it has to take money off the non-government sector either via taxation of bond-issuance.

However, in a fiat currency system, the mainstream analogy between the household and the government is flawed at the most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

From a policy perspective, they believed (via the flawed Quantity Theory of Money) that “printing money” would be inflationary (even though governments do not spend by printing money anyway. So they recommended that deficits be covered by debt-issuance, which they then claimed would increase interest rates by increasing demand for scarce savings and crowd out private investment. All sorts of variations on this nonsense has appeared ranging from the moderate Keynesians (and some Post Keynesians) who claim the “financial crowding out” (via interest rate increases) is moderate to the extreme conservatives who say it is 100 per cent (that is, no output increase accompanies government spending).

So the GBC is the mainstream macroeconomics framework for analysing these “financing” choices and it says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt (ΔB) over year t plus the change in high powered money (ΔH) over year t. If we think of this in real terms (rather than monetary terms), the mathematical expression of this is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit (BD) = Government spending (G) – Tax receipts (T) + Government interest payments (rBt-1), all in real terms.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. It has to be true if things have been added and subtracted properly in accounting for the dealings between the government and non-government sectors.

It never enters the IMF analysis that governments would consider using the ΔH route. They have erroneously constructed that option as being always inflationary – the demonised “printing money” option – so it is always assumed that governments will continually to (unnecessarily and voluntarily) use debt issuance to match $-for-$ their budget deficits.

More sophisticated mainstream analyses focus on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. They come up with the following equation – nothing that they now disregard the obvious opportunity presented to the government via ΔH.

So in the following model all net public spending is covered by new debt-issuance (even though in a fiat currency system no such financing is required). Accordingly, the change in the public debt ratio is:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant. For example, if the primary deficit is zero, debt increases at a rate r but the debt ratio increases at r – g.

Thus, if we ignore the possibilities presented by the ΔH option (which is what I meant by current institutional arrangements), the proposition is true but largely irrelevant.

So the IMF Figure 1 that follows is based on this framework with the primary balance and the (r-g) on the vertical axis and the debt ratio on the horizontal axis.

The IMF describe the model in this way:

The lower intersection between the primary balance and the interest payment schedules defines the long-run public debt ratio to which the economy normally converges. This equilibrium is conditionally stable: if a shock raises debt above this point (but not beyond the upper intersection), the primary balance in subsequent periods will more than offset the higher interest payments, returning the debt ratio to its long-run average, d*.

The upper intersection (at d_bar – the bar is the line on top of the d) describes:

… a debt limit … above which debt becomes unsustainable: if debt were to exceed this point, it would rise forever because (in the absence of extraordinary adjustment) the primary surplus would never be enough to offset the growing debt service. Therefore, public debt is unsustainable and, in effect, the interest rate becomes infinite as the government loses market access and is unable to roll over its debt.

So the upward bend in the red line is attempting to capture what the IMF claim is the reaction by the financial markets in search of a risk premium as debt levels rise.

Once the economy goes beyond d_bar the IMF claim “there is no sequence of positive shocks to the primary balance (in the absence of an extraordinary fiscal effort) that would be sufficient to offset the rising interest payments. Therefore, debt becomes unsustainable, and the interest rate effectively becomes infinite”.

So fiscal space is defined within this framework as:

… the difference between the current level of public debt and the debt limit implied by the country’s historical record of fiscal adjustment.

I will leave it to interested readers to work out how they come up with their results. Briefly, they run some very dubious panel data regressions (with major endogeneity problems – for those technically minded) to estimate two relationships which form the basis of their subsequent analysis.

The first relationship is what they call the primary balance reaction function which is a regression estimating how the primary budget balance (that is, the difference between government spending and revenue excluding debt servicing payments) as a percent of GDP reacts to the debt to GDP ratio. This is the thick black line in the figure.

The second relationship is the interest rate schedule (the red line) which is similarly estimated by panel regressions with country-specific fixed effects.

The regressions have serious issues and basically conflate countries with monetary systems which render them non-sovereign and sovereign countries. They ignore a range of other factors including the capacity of the central bank to control the yield curve.

So all they do is run a few regressions (with minimal reporting about the diagnostics the econometricians such as myself use to judge how robust the results are), fudge some of the future observations out to 2015 (see next), and then do some subtractions to get a figure of fiscal space. Absolutely no understanding of how currency systems operate.

It is important to understand that in computing their estimates the IMF:

… replaces historical averages with IMF projections of long-term government bond yields and for GDP growth (WEO). With minor exceptions, projected interest rate-growth rate differentials are considerably less favorable than historical differentials, reflecting the expectation of both higher interest rates and lower real GDP growth rates.

So while anchoring the lower intersection point on the basis of historical data they decide for projections to make up long-term bond yields and future growth rates. The model they used to do that is of-course the flawed mainstream framework. Not only have they consistently projected higher yields when the reality is that long-term yields remain low and are falling.

How do they cope with the two-decade low yields for Japan which has the highest debt-ratio of any nation? So essential data being fed into their modelling is just fabricated by the institutional which has demonstrated an appalling forecasting record in the past.

The IMF failed to see the crisis, underestimated the severity in the early period and has consistently overestimated the interest-rate effects of deficits.

In applying their definition of fiscal space they compute it as the:

… difference between the debt ratio projected for 2015 and the debt limit … [d_bar]

After all the statistical gymnastics the IMF staff try to tell us how important their results are:

… a key issue for policymakers is to have information about where the danger points are as far as public debt sustainability is concerned, so that timely action can be taken to steer the economy away from possible limits on public debt. A second issue relates to situations in which the economy-as a result of some shock – actually finds itself on an explosive debt path, and the options for restoring fiscal sustainability in such situations. This note aims to shed some light on both questions.

If the IMF results had any meaning or applicability at all the Japanese government would have severely cut its discretionary budget some years ago during the period when fiscal policy was propping up its ailing economy. Not only would this have pushed the budget further into deficit via the automatic stabilisers but the economy would have been plunged into a depression.

The same applies to all sovereign countries. Following the IMF approach would severely damage their real economies and fail to reduce the debt-ratio anyway.

The IMF also claim that their “analysis does not take account of rollover risk” and so (allegedly):

governments will typically want to keep their debt well below the estimated limit, to ensure that fiscal space remains comfortably positive …

Which is the ideological message that the IMF wants to pump into the policy space.

In other words, the government should be duty bound to run what may be very tight fiscal positions in situations where the other macroeconomic parameters such as private saving ratios etc are causing aggregate demand to fall and output and employment to contract.

Never mind worrying about full employment or other dimensions of public purpose which should drive the implementation of fiscal policy.

Further, the fiscal positions might be the result of sharp shifts in the automatic stabilisers as private spending collapses but still the government should resist allowing their deficits to expand beyond some mythical frontier defined by the IMF.

Finally, there is zero rollover risk for a sovereign government. It can always service its interest payment obligations and debt maturity payments. When has an advanced sovereign nation (that is, one which issues its own currency and floats it in foreign exchange markets) ever defaulted on its debt repayments or debt-servicing payments? Answer: Never for financial reasons.

The suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – shows how we might better assess the concept of fiscal space and fiscal sustainability.

I note some commentators here consistently claim I am soft on the debt-issuance by sovereign governments as if I think it might be useful. I would have thought the message I provide is to the contrary. Debt-issuance by a sovereign government is primarily an act of corporate welfare. It is unnecessary and does nothing to reduce the inflation risk of net public spending.

No sovereign government should issue any debt at all!

However, I consider the dynamics of debt-issuance regularly because the political reality is that governments are caught in the neo-liberal spell which has somehow persuaded them that gold standard/convertible currency practices remain relevant in a fiat currency system.

Postscript to Australian National Accounts data

In yesterday’s blog – Australia continues to grow but the signs are not all good – I noted that the June quarter growth figures announced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics were positive but there were warning signs that the growth was due to unsustainable factors.

Part of the growth was due to the strong trade performance in the June quarter. I noted that this would slow as the year progressed due to the likelihood that the booming terms of trade would subside.

Remember that National Accounts data tells you what happened some months ago which is interesting but not necessarily a sign of what is currently happening. The most recent labour market data which I covered in this blog – Labour market – going backwards now – tells us that in July full-time employment growth was negative and overall total employment growth was not sufficient to absorb the labour force growth. As a result unemployment rose and given the dominance of part-time employment, underemployment also would have risen.

Today, the ABS released the trade data for July which tells us the trade surplus fell by nearly 50 per cent as a result of an absolute fall in exports and a slight increase in imports.

The bank economists were once again caught up in their own boom rhetoric and had predicted a surplus of $A3.1 billion whereas the ABS reports that it was $A1.89 billion down from $A3.44 billion in June.

One month’s data is nothing to hang a story on but what this result tells us is that when the National Accounts are compiled again for the September quarter the trade contribution to real GDP growth is likely to be smaller than it was in the June quarter.

Combined with the reduction in government contribution as the fiscal stimulus wanes and the pursuit of (manic) surpluses begins, real GDP growth is unlikely to be as strong as it was in the June quarter.

Conclusion

After reading the paper published by the IMF’s Research Department on fiscal space I suggest it would be more appropriate to rename that Department the Propaganda Bureau.

That is enough for today!

I do not understand this government budget constraint equation. Shouldn’t it be (r-g)/(1+g)? What am I missing here? I googled for an answer and I found tons of PDF about GBC but all with the mentioned equation (r-g)*B/Y. GBC seems to be very popular and most of the economists can’t resist to add some glee like “Too bad. There’s no free lunch.”

Bill, I am new to your site – in no way related to economics as subject – but immensely interested in finding the facts as this has got profound impact on my life. I would appreciate help with understanding some basic facts which I am finding it tough to comprehend.

I have been exposed to too much austrian and hyperinflationist thought process. I was falling prey to deflation followed by hyperinflation as US fail to sell treasuries and meet its own obligations.

But then i found your site and it made atleast one thing pretty clear to me – hyperinflation is totally out of question as the circumstances required to trigger that are missing.

However, I do have my doubts persisting about deflation. One thing obvious from austrian school is that overdose of debt leads to deflation when the asset bubble is pricked. And as a result of that there are widespread job losses combined with credit contraction as more and more number of people try to get their domestic balanace sheets in order.

This follows a contraction in businesses as companies try to remain afloat by cutting costs and jobs.

Now according to you, government can replace private business expenditure and spend more to cover the defecit.

But, this recession being a demand side recession rather than being a supply side recession, how can govt spending stimulate the economy effectively by just creating more spending programs?

One option is to mass forgive the loans (going by the assumption that money is just a sequence of binary digits) – but that option seem to be a very bad option politically as well as economically.

How do you envision that MMT can help overcome recession in such a scenario?

Your thoughts would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks,

Newbie

When US fed started buying “risky assets” from banks – i had come to conclusion that governments can practically do whatever it takes

Stephan,

Here:

A Practical Guide to Public Debt Dynamics, Fiscal Sustainability, and Cyclical Adjustment of Budgetary Aggregates, – IMF Technical Notes and Manuals by Julio Escolano

site_www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/tnm/2010/tnm1002.pdf will let you see the (1+g) factor. The equation without (1+g) is obtained using continuous time formulation.

The problem with such equations is that they assume some sort of exogeneity – such as they keep the budget deficit as fixed. A more correct way to do so is to “endogenize” it.

However note that some formulaes in that pdf are useful such as equation (16)

Krugman has admitted some of his mistakes . . . until he embraces MMT, he would make more avoidable mistakes relating to economic forecasting in the future . . . http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/mistakes/

Krugman said

———————————————

“The second was circa 2003, over the Bush administration’s use of the illusion of victory in Iraq to push through more tax cuts, even though the optimistic budget projections used to justify the first round had proved completely wrong. It’s worth pointing out that the situation was not at all like the present, where I support temporary deficit spending to deal with a depressed economy; the Bushies were pushing permanent tax cuts that had nothing to do with economic stimulus, and did so at a time of war with no offsetting spending cuts (and then pushed through an unfunded expansion of Medicare too). This struck me at the time as banana-republic behavior, and still does.

However, I wrongly believed that markets would look at it the same way, and that they would lose faith in American governance, driving up interest rates on our debt. Instead, bond investors discounted the politics, and acted as if they believed that America would eventually pull itself together and start behaving responsibly. The jury’s still out on that, but clearly my short-run prediction proved wrong. ”

———————————————–

The above statement alone proves that MMT is valid and only MMT could provide a logical explanation on why the bond market behaves like that

I think the IMF concept of “fiscal room” is quite right! Some nations have less fiscal room and others have more. The latter will not take a chance to decrease its “fiscal room”. They are waiting for the advanced nation which unfortunately have less fiscal room. This crisis cannot be resolved so simply! A few months back, I saw a comment by our host that trade deficits give governments more room to increase fiscal policy – something which is just the opposite of what I am writing.

The general statement made by neoclassicals (and Keynesians included) is that the government should aim to hit a primary surplus to make the public debt/gdp sustainable. Others – a few Post Keynesians included, say that since the interest rates are at the discretion of the central bank, this condition is not strong. They are wrong as well. The last statement says nothing about the rest of the world’s net asset position.

A right way to put is to say that even if the government is not pursuing a discretionary policy to target primary surpluses, and even if the interest rates are higher than the growth rate, there is no need to worry. Of course, the government needs to punish the money hoarders and the rentiers else the public debt will start exploding relative to the gdp and interest payments to the money hoarders too – an embarrassing situation. The government needs to make sure that the debt is picked up uniformly across its citizens.

Now include complications about the trade performance with the rest of the world and complications related to the currency, one lands into the area of immense complexity. The MMT stand is that the government just credits bank accounts of the foreigners, whats the worry. Okay – the foreigners purchase private sector debt and equity, thats certainly a burden isn’t it ? So if a foreigner purchases the latter and not government bonds, its a burden and not in the opposite case. This is a paradox! And what is the resolution of this paradox ? The resolution is that both are burden because crediting bank accounts of foreigners in perpetuity decreases the fiscal room 🙂

So we have opposite views – MMT says no such thing as fiscal room and hence enjoy net imports and credit foreigners bank account and my position is that since crediting foreigners’ bank accounts gives less fiscal room, someone find a solution please!

There are so many complexities that it is really difficult to make general statements. For example, a country growing may not find itself in trouble because of the external sector because equity inflows may lead to increases in foreigner reserves and not lead to currency falls. However I can make some weaker statements. Such as: if a debtor nation takes discretionary steps to target net exports, it can enjoy more fiscal room and enjoy the benefits of imports ;-).

The subject is complex – it took me a while to understand this – thanks to Wynne Godley and his stock flow models and his sectoral balances.

Dear Ramanan [at 2010/09/03 at 3:08]

“crediting bank accounts of foreigners in perpetuity decreases the fiscal room” – not if the crediting is in the currency of issue.

Fiscal space or room is about real resource availability. Thinking it has something to do with financial ratios is an error. I am sorry you have lost that insight.

best wishes

bill

Ramanan said:

”Now include complications about the trade performance with the rest of the world and complications related to the currency, one lands into the area of immense complexity. The MMT stand is that the government just credits bank accounts of the foreigners, whats the worry. Okay – the foreigners purchase private sector debt and equity, thats certainly a burden isn’t it ? So if a foreigner purchases the latter and not government bonds, its a burden and not in the opposite case. This is a paradox! And what is the resolution of this paradox ? The resolution is that both are burden because crediting bank accounts of foreigners in perpetuity decreases the fiscal room.”

I disagree. With respect to currency, in Canada over the past 20 years we have had huge swings in the value of our currency vis a vis the US dollar to the tune of 30 to 50 percent, often over fairly short time periods. These have affected the tradeable goods sectors, certainly, sometimes positively sometimes negatively. But they have not led to financial crises nor have they led to more than very slight changes in the annual inflation rate, perhaps 0.5 to 1%. Yet Canada imports lots and lots of stuff.

With respect to unwanted foreign control of real national assets due to large interest payments to foreigners, each country is free to place limits on foreign investment as it sees fit. Canada does this today and has done it more extensively in the past with substantial effect. I don’t think many people here care who owns office buildings, fast food chains, or some manufacturing. However, many, if not most, are concerned about who owns our banks, media, telecommunications, and oil and gas industries, for example. In those industries there are now, or have been in the past, strict controls over foreign ownership. Foreigners hold large quantities of Canadian dollars and have been interested in buying large parts of these profitable industries, but have not been allowed to do so.

Allow me to add that a recent benefit of this was that our nationally controlled banking system which is heavily regulated experienced almost none of the problems faced by most other developed countries. Given our proximity to the US and the heavy influence we normally feel from there this was quite remarkable.

By the way, I did read the very long exchange on Warren M’s blog and saw nothing that confirmed your concerns with MMT to me for the reasons outlined above, at least with respect to Canada. This is not to diminish what might happen in a poorer country by any means, in particular if it must import all its basic foodstuffs. But MMT has never pretended to be a miracle cure. I recall Bill mentioning that Greenlanders will need to get used to eating a lot of fish even if they use MMT methods to extricate themselves from their problems!

In order to shake off the arrogant of IMF, I think there will have to be multitudes of Argentinas and in grand scale. Yeah … open revolt. But no Western elite, as of today, is going to provide the necessary leadership for this. (Their austerity-ism shown in the latest G-20 summit should be telling.) Only late-comers and developing countries (such as the Asian ‘Tigers’, Argentina, all of them have had first-hand experience with the economic sagacity of IMF not too long ago!) could do so, if they feel they have been pushed around by IMF a bit too much. In short, IMF is equivalent to a blind leading a blind. Perhaps IMF should change its acronym to AMF — Austerity Monetary Fund. At least the latter choice of acronym more accurately describes what they are all about. 😀

Newbie:

Governments can add to private demand by giving private citizens more money. The easiest way is with a job guarantee. If they paid a bunch of unemployed people minimum wage to do socially useful stuff, then those people would spend that money on groceries and rent. Woolworths or Coles would then need to restock their shelves a little more, and buy more apples and steaks from farmers. Those farmers would then make more money and spend some of it etc etc.

In other words, any injection of government money into the system, especially directed at people who immediately spend most of it instead of saving it, gets spent and respent multiple times before it leaks away to nothing though savings. Each extra purchase adds to aggregate demand. That’s the multiplier effect.

Grigory,

Thank you so much for that useful insight. I get your point – basically govt can pay the unemployed minimum wage in the form of unemployment allowance. People can spend that money and it has got multiplier effect. For government money is produced by waving magic wand and they can spend as much they want.

But then does it not mean that government is providing incentive for not doing work? Many people in low income bracket would be tempted to basically do nothing and earn a check from the government.

Also, more money in the system means individuals would have to be taxed more for sucking the money out (tax the rich) or in form of higher interest rates to rein in inflation. And would that not result in decreased private sector productivity?

Thank you!

Bill,

Have to disagree on this one

I used to believe that but unlearned that ;). If net exports compensate for this, than doesn’t decrease the fiscal room. It has to do a lot with the definition of money in my view. However, whatever the definition is, the possibility of foreigners’ claims increasing with no limit is an implausibility. Sooner or later the interest payments and dividends start exploding. Doesn’t really matter if the coupon payments is coming from the State or the citizens. Its easier to say that these numbers are smaller compared to other numbers but the important thing is that these numbers keep accumulating. We don’t see them growing without limit because the governments take austerity measures – which in turn reduces the trade deficits. Some nations end up with a devalued currency and sometimes it helps them become exporters. However this is due to the discretionary decisions of the government and the citizens to become exporters. There is nothing automatic about this.

I agree that real resource availability is important. A nation can have the public debt/gdp at 40% while another may have it at 80% with both doing equally well. However when nations start interacting, the dynamics this gives rise to leads to all kinds of complications even before questions of real resource availability becomes important. Trade deficits lead to unemployment. However relax fiscal policy and you have more indebtedness to foreigners because the trade deficit widens. This process cannot go on forever. The MMT crib on this would be “what is the meaning of indebtedness in your own currency” etc. I think it doesn’t matter. In fixed exchange rate setups, it increases fragility. However, it doesn’t mean that all problems go away in floating rate systems. There is a tremendous gain in the flexibility offered by flexible exchange rates. However, nations should be pro-active about their external sectors to enjoy the benefits of fiscal policy.

There are two ways to write a narrative about the government sector in a closed economy. One is to say that the government can be indebted forever with no worries (except possibilities of supply side issues). The other is to say “debt is not debt”. These two seem equivalent. The trouble with the latter is that when carried over to a narrative of open economies, one loses track and leads one to make statement such as liabilities to the rest of the world is not really a liability without worrying about what is happening to the exchange rate in the narrative. And the behaviour of the government sector in the story when there is an issue.

Keith,

Will get back to you on Canada. You had mentioned this to me before as well, but I didn’t check up what all happened to the nation.

You tend to think that foreigners not being able to do anything except purchase financial assets does the trick. However, I don’t think so. There is still trouble. Imagine the case of the US. Do you think it is even remotely possible that there exists a scenario where the US government’s coupon payments to foreigners keeps increasing without a limit? 50% of GDP, 100% of GDP, 250% of GDP ?

Keith,

What I meant in the last comment is that “your policy” will lead to the situation I described above.

Now coming back to Canada, I happened to quickly check two posts – one by Marshall Auerback and the other one by Paul Krugman quoting Marshall.

It seems that in the 90s, the exchange rate just kept devaluing – though I don’t know why. At any rate, exchange rates move in complex ways and it is difficult sometimes to even explain it ex-post.

At the same time, exporters took massive advantage of this and Canada seems to have had an export boom which seems to have helped in spite of the government going into austerity. Maybe one could say that increased incomes led to more tax payments and lesser government spending, while the government itself was trying to go in that direction.

At any rate, it is this which may have helped the nation. Imagine if Canada had stopped exporting thinking “exports are costs, imports are benefits” …

Dear Ramanan [at 2010/09/03 at 17:47}

You said in relation to debt/ratios etc:

There is not a lot of evidence to support your claim. There is no significant relationship found between exchange rate movements (or terms of trade movements) and budget deficit positions or debt/GDP ratios in the literature.

Further, there is no systematic evidence to show that debt/ratios stabilise because of austerity. History will tell you that growth has been the vehicle that keeps debt ratios at some stable point and fiscal policy is always positively and significantly related to real GDP growth.

Further, the trade imbalances you are now focusing on are typically reversed by exchange rate changes if the currency floats. Just look at Australia for evidence. The exchange rate was the lowest in my life in the early 2000s when the budget was in record surpluses. It is now strong when the deficit is large by historical standards. The terms of trade fluctuations come and go with no correspondence to domestic policy. That is what life is like in a small open economy. We are not an advanced industrial economy!

Further, very rarely does an exchange rate collapse and when they do these events are not systematically related to growing budget deficits.

As long as the government does not borrow in a foreign currency, then there are no financial constraints on fiscal policy that the government doesn’t voluntarily accept. A sovereign government can always focus on maximising the utilisation of its domestic resources. It does not have to engage in austerity. That does not say however that the private sector is immune to exchange rate swings. Certainly, if the foreign sector loses a desire to accumulate financial assets in the local currency then clearly the real terms of trade will deteriorate and the citizens will be able to purchase less imports which might include essential foods. Also a private sector heavily exposed to foreign-currency denominated debt is exposed to insolvency if the export side experiences a negative shock.

A nation running a fixed exchange rate is just as vulnerable to currency raids as one running a fiat currency.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Thanks for the reply.

You make interesting points about relationships between various quantities and in fact the lack of it.

I have no issues with the statements.

Neither am I arguing against fiscal policy. Never have. I am arguing that fiscal policy is difficult to use if the trade performance is not good.

The trouble is that the lack of relationships make it even more difficult to argue out things. Central banks have to raise rates when there is some issue with the exchange rate, fixed or floating. A patient has to eat medicines to struggle with cancer even though it may not help. Similarly nations may have to go into an austerity whether it is useful or not. This is with the hope that tightening helps to reduce trade deficits.

I also understand that a government can be aggressive and increase fiscal policy and steer the economy by growth. India can certainly do that now and has done that. Not sure if all nations can. Its a political choice even if government officials come to understand how economies work.

Coming to currency collapses, I understand that it doesn’t happen frequently. However, that is because the governments have gone in the route where they have curbed demand.

Also currency movements making an effect to trade imbalances is again a complicated issue. My nation’s exports will increase if the exporters make sure that they are competitive etc. It is not automatic. Its a supply side issue. There are two things – price competitiveness and non-price competitiveness. The exchange rate movement just helps the former.

Also not arguing for fixed exchange rates either.

geez, guys, so many of you are saying “government to MAKE this happen –> more control” make that happen –> more control…make sure this and that….

really, what kind of society do you wan to live in?

or is economics so difficult to model and predict because rational human choice does not fit well with a broad base of quasi-scientific assumptions about how economies operate?

i guess giving govts more and more and more and more control takes away the complexities involved with modelling human rational human decisions, eh?

well, more power to you on that…and to the govts and the central banks, i guess…! 😉

…and stimulus (govt giving people money) does not actually work IN PRACTICE (ie. different to theory!) because the context is that of heavy, controlling (systemic and psychological) debt loads…so when people are “given” money by govts expecting a Keynesian multiplier, most people choose to use most of the money to pay off debt instead…a sensible rational choice.

To get the Keynesian thing working properly, you will need – wait, there it is again! – more govt control! ie. where you TELL (or coerce if you are in a “free” society) the populace to spend their stimulus payment instead of being silly and being down debt.

Hmmm….

Enough of the rant from the Process Engineer, eh?

Regards…

Hi Ramanan,

In the early 1990s the Canadian federal government embarked on a program to decrease the fiscal deficit independently of the exchange rate and foreign trade balance. In fact it followed the free trade agreement with the US and was the pretext to decrease some of our social programs (unemployment insurance and welfare) down to US levels. Luckily for the government the US independently began an economic expansion shortly afterward which allowed Canada to export more, offsetting the fiscal drag. Canada’s currency also depreciated significantly at the time, although I can’t recall why. Typically the US-Canada exchange rate is mostly affected by the discrepancy between the overnight interest rates between the 2 countries as well as the level of commodity prices – higher prices leading to a higher value of the Can$. Note however in this case austerity preceded a decline in the exchange rate which is the reverse of what you are suggesting. I think this illustrates that fiscal austerity and exchange rate are not necessarily related.

What I mostly take from all this is what you say, that these issues are complicated. But I don’t conclude that the limited MMT take on this is incorrect. With respect to what would have happened if Canada stopped exporting, it would have been disastrous of course! But that would never happen in isolation. There would be policies and resources to develop new industries to replace imported goods and to develop the internal market in many other ways. With respect to the US coupon payout to foreigners reaching 50-200%, the extreme scenario has virtual economic collapse of the US embedded in it so all kinds of turmoil would be going on and probably the least concern would be the exchange rate! In a way these last two things illustrate the problem I have with your problem (!). It seems to me you are constructing rather extreme scenarios and saying MMT doesn’t resolve things. I agree completely. That’s my point. MMT helps understand what the possiblities are but won’t turn a poor country with no resources into a wealthy one. It does raise the likelihood of full employment though so at least people are not destitute and in despair.

As an aside on what a poor country can and cannot do, a year and one half ago I spent time in Cuba outside a resort for the first time. Cuba is a very convenient sun location for eastern Canadians – close,cheap, safe – and I had gone several times to a resort for a week or two. I had a little time so I decided to drift around the Eastern part of the country for a few weeks, from one medium or small sized town to the next, also hiring people to speak Spanish with me. I spoke to quite a few people, went into their homes, went out on the town with them, met a judge, university students, bed and breakfast owners, and others. Setting aside political issues, two things stood out. One is that they have all the basic services we in the developed countries have (except the US) – accessible free daycare, free health care (except pharmaceuticals outside of hospitals), good free education. So far so good. But the material standard of living for most people was very very low and easily available food was very monotonous. If you didn’t have a family member working in the US or Canada, or in a Cuban resort, providing additional income day to day life was very difficult. The judge I mentioned worked serving tourists in a resort to earn money. Some of the people I met lived in a house that would barely be a shed in Canada. There was a lot of frustration because their were few outlets for people’s skills. A university prof I met earned much less than a cleaner earning tips in a resort. My point is that a poor country with few resources is still a poor country even if it is able to mobilise its people to provide services as MMT would allow. I have no idea how Cuba’s monetary system works but I do know the country is recognised as an outlier in that with a very low per capita income it provides remarkably good services and basic food to its people. It nonetheless remains a very poor country with much of the frustration and unfairness that entails.

Newbie:

It would be far more preferable to get people on a job guarantee – that is, pay them minimum wage for doing something socially useful like cooking meals for the elderly or cleaning graffiti etc. In other words, stuff the private sector won’t touch with a ten meter pole.

As for inflation, as long as the private sector has excess capacity it can absorb any extra demand by hiring more people. No one sets prices based on the treasury’s estimates of the money supply – they set prices based on a complex interplay of supply, demand and competition. Most businesses aim for higher market share, especially long term, and prefer to produce more of their product than to raise prices when hit with an unexpected demand wave.

The only time inflation becomes a risk is when unemployment is low, and businesses can’t hire more people easily to cope with extra demand. At that point you would have them either raising prices or raising wages to lure more workers in. That’s why it’s critical to stop spending when you reach full employment. That’s where the job guarantee comes in – it automatically contracts spending because when the private sector is doing well, people leave the JG and work in the private sector.

So one of the brilliant elements of the JG is that in recessions when the economy needs more spending, it expands (as people lose their jobs), and during boom times, it contracts as people leave for greener pastures. This is precisely what happened in Argentina when they introduced a limited JG.

stewart:

Private citizens repairing their balance sheets is a *good* thing. Private debt is unsustainable – it has to be paid back eventually. If government spending allows people to get rid of their credit card debts, the economy ends up more stable in the end. After all, the latest recession happened because too many people had mortgages they couldn’t pay back.

However, most people in lower income taxes spend the vast majority of their money instead of saving it. It’s the rich who save most of their tax cuts.

So no, there’s no need for more government control in order for stimulus to work. Here in Australia the government just gave everyone $900. No instructions on how to spend it, no “socialism” or whatever it is you are terrified of (I assume you are American?). It worked. Retail sales got a huge bump.

Keith,

You said

If you don’t mind my usage of some words – its a bit disingenuous to say that a few variables are not related. Consider the following statement – equity prices and earnings news releases do not have any correlation. Does that mean that board members of firms can stop caring about profits ? Of course not! In fact if you see some recent articles on Turkey, it shows that the exchange rate has appreciated in spite of continuous trade deficits. I certainly have these things on the back of my mind, as I have been trying to argue these things out over the past 2-3 months.

Neither are my examples some rare cases! It is affecting the biggest nation in the world – the United States. Okay you can argue that fiscal policy is the only way out right now and I agree. However, the long term solution cannot be fiscal alone. Refer you to the table L.107 in the Fed’s Z.1. The RoW’s Total financial assets is $15.63T and liabilities $7.36T and the difference is $8.27T !!!

Thats what the US owes the rest of the world! Now the simplest way to dismiss such things is to say “what does it mean to be indebted in your own currency” etc. I think such arguments are seriously misguided. Thats fiat money theory. Money is fiat, it is also credit and it is also “an international thing” borrowing words from John Maynard Keynes.

This process has no limit. It will go on as long as the markets allow it. Now some MMTers also say that but I do not think they have worried about exploding interest payments to foreigners. Instead something like this is said “government can always …”

but …

Relax fiscal policy more and this will increase even further! Even now it is increasing because of the trade deficits.

Also note – my views not not outside Post Keynesianism. It is only from them I have learned these things.

There are several possibilities of course such as the dollar falling and increasing exports by some amount. However hoping for market corrections is nothing but going back to Neoclassical Economics.

Also note if the US’ exports increase, the Rest of the World needs to import that stuff – will they agree to do so ?

Ramanan, if you push something to the limit then whatever it is it will eventually break down. There is a limit to everything. But then why would you as a responsible government just sit there and watch until something breaks terminally down? There can be plenty of measure taken well before it does break down.

And on the other side of the story. How much foreign reserves does China need? I believe it is clear by now that it is not the reserves per se which matter for China but the import of jobs while reserves serve as a political tool to expand Chinese influence around the world. The more reserves they have the more real things they can grab. And those who sell real things obviously want foreign currency. So it is much more a political tool than economic or market one.

Ramanan,

“and the difference is $8.27 T”

Careful – to get the full US perspective, you have to add in the memo item of more than $ 4 trillion in foreign equities held by the US.

That chops the difference down to closer to $ 4 trillion – which is the net international investment position as it is normally defined

(for the US, a negative position, but still less than the cumulative current account deficit)

(They segregate equities held as a memo item to be consistent in use of the term “liability” from the ROW perspective)

Oops JKH, thanks for pointing out – else I would have believed that till the next Z.1 comes out. (I actually remembered numbers between 40-60% of GDP, this is lesser than 40%). Australia probably is 56.21% if I remember my observation a few days back.

In fact in Bernanke’s “global saving glut” speech, he mentions about one option of investment abroad which might bring back some reversal.

Your point about cumulative versus the number in discussing is an interesting one. I think the former is around 50% is still a good number to know.

There are some rules of thumb that can be made which I am not sure at this moment. Such as the US needs to grow atleast x% where x depends on public debt/gdp ratio and the current account deficit. But growth may lead to higher current account deficits!

Sergei,

When China exports to the US, it doesn’t just get the dollars for the products. There are other changes happening in the various sectors’ balance sheets and transaction flows.

Is there a limit? – absolutely not. Even if there is, there are zillions of countries who will try to get USDs.

I liked Krugman’s take on this.

I understand that the US government’s economic policies are senseless and they simply do not understand fiscal policy, but there are other things happening in international trade as well. I know the argument against it “imports are benefits” etc. I mean yes imports are benefits but so is taking a loan to buy a villa. My arguments are a challenge to statements such as “we do not borrow from the Chinese”. But thats fiat money theory. Yes, the US dollar is created inside the US, but thats a simultaneous creation of asset-liability pairs. The “Flow of Funds accounts” do not give that message. It doesn’t give out the dynamics of the story as well but it presents it in a format which is upto you to interpret and theorize – which is great thing.

Ramanan,

1. The difference between stock and cumulative flow is due to valuation of course. It’s interesting how valuation has worked to the US advantage – the “US as hedge fund” effect.

2. Important to examine the net income cost of the stock position. It’s not only been low historically – it’s been negative (not sure exactly where it is now – probably low positive). That’s the “US as risk transformer” effect.

JKH,

Yes interesting point in point 1.

For point 2:

Z.1 F.107 (line 7 – line 4 – line 3)/(GDP in the respective periods) ?

Treasury securities held by foreigners is $4T – something which can be used to criticize what I am saying (-;

“Z.1 F.107 (line 7 – line 4 – line 3)/(GDP in the respective periods) ?”

appears to be about right, although the official stats showed net positive income a few years back

Googled the following from back from 2007, which you may find interesting; refers to the net positive income:

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Global_Economy/IB27Dj02.html

Elementary explorations in fiscal mamagement.

Suppose (d) is the public dect to income ratio, (r) is the real interest rate, (g) is the real growth rate of income, (π) is the inflation rate (p) is the nominal primary deficit budget balalance, (m) is the monetary base to income ratio, ((φ)<=1) is the fraction of public debt retired via open market operations of the central bank, ((μ)<1) is the share of the deficit balance to the monetary base. Then we have,

d(t)-d(t-1) = (r-g-π)d(t-1) – (g+π)m(t-1) – rφd(t-1) + p(t)

Assuming a steady state situation with debt stability, d(t)-d(t-1) = 0. Then, and after some simple manipulations,

[(g+π) – r(1-φ)]d(t-1) = p(t) – (g+π)m(t-1).

Notice that if (d=0), as no public debt remains outstandind and all (p) creates net monetary base, and (p(t)=μm(t-1)), then,

g+π = μ

steady state nominal growth of income is equal to the share of the steady state deficit spending balance of the monetary base outstanding.

JKH,

Thanks for the article. What do you mean by official ? Wouldn’t the Fed use official figures only ?

The numbers in the table on page 40 here ? Annual Revision of the U.S. International Transactions Accounts

link_http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2010/07%20July/0710_intl-accts.pdf

In particular, the item “Balance on Income” – has yearly data from 1999.

Panayotis,

How does the central bank “retire debt by open market operations” ?

Ramanan,

Yeah, I guess its BEA (I used to follow this stuff via Setser, without looking it up).

Yes – appears to be “Balance on Income” line on page 5 of your link/page 40 underlying.

Can’t believe it – not only still positive, but increasing!

Yeah .. back of the envelop calculation suggests a 2.5% differential in the returns.

Ramanan,

I do not see what you do not understand and I am surprised at your question. The CB can buy public bonds in exchange for reserves and as long as held by the CB which is consolidated as part of the state authority, the government owes to itself and any interest paid on this debt is returned to the treasury net of any transaction costs. “Retirement” is only a technical term for analysis purposes during the period (t). Theoretically, these bonds might never return in secondary markets or reused in future OMO. If repurchase agreements are involved the “retirement” aspect has a shorter duration and it also depends who receives the interest income paid. Obviously, if none of this is practiced and refinancing facilities are the mode of operation (φ) = 0.

I hope it is now clear to you.

Ramanan,

“But thats fiat money theory. Yes, the US dollar is created inside the US, but thats a simultaneous creation of asset-liability pairs.” Please explain. You continuously, bring up foreign trade and current account balances, but what is your argument. You are unhappy with the MMT position but what is your hypothesis? I tried to stay out of this but you seem to come back again and again…….and maybe I am missing some profound point. Please enlight me. I mean it sincerely.

Panayotis,

Understand about your point about retirement. Just that hadn’t seen such an expression elsewhere.

I don’t have an hypothesis – just studied much of Post Keynesian theory. The external debt matters for a nation just like it matters for a corporation. A growing debt generates a growing debt burden.

Now it can be said that the government can compensate the loss of employment due to the continuous current account deficits but that comes with higher indebtedness to foreigners and increased burden on servicing the debt. It can be said that the government is not constrained, but this process cannot be allowed to go on. It has to show up somewhere and likely the exchange rate. Now, the way the fx rate move is immensely complex – I do not claim that the currency will fall or that there will be a crisis. What I am saying is that it is unsustainable. Just like the debt explosion in the United States which happened in the late 90s and the 2000s, it is difficult to point out where it will end.

You brought the issue of debt sustainability in your comment. Note – an endemically unbalanced trade deficit keeps increasing the budget deficit and the public debt eventually will need to rise faster than incomes because of blowing of interest payments to foreigners.

Now, there is no government which compensates employment losses by relaxing fiscal policy so easily. So in the real world as opposed to an MMT proposed world, trade deficits are a cost not a benefit – if one wants to categorize imports and exports in a digital way.

More importantly, this is affecting advanced nations – the United States and Australia.

Ramanan,

You do have a hypothesis and I respect it. The fiscal space/capacity/leverage issue imposed by foreign indebtness is a real economic relation and not a financial one. It comes about because of a structural imbalance when an economy suffers from an effective resource constraint and has an inelastic demand for imports (strategic) and faces an elastic demand for its exports and capital inflows that are not desirable to be made by foreigners at any exchange rate. An increased burden of servicing the foreign debt becomes effective under these circumstances. This type of economy must resolve its real sector problems before it can practice effective fiscal policy. However, this is not a point about the effects of a monetary regime.

A growing foreign debt and its ratio to GNP is sustainable if it leads to net investment in productive capacity and corresponding current account adjustment assisted by flexible exchange rates. However, the real structural issue has to be resolved. Sometimes import and foreign investment demand policies can create an export orientation and attractive conditions for capital inflows and resource constraints can be reduced. Maybe fiscal investment can help in this direction of export/foreign investment capacity, so potential output can expand.

Panayotis,

The phrase “Foreign investment” doesn’t give a very correct picture of whats happening. The root of the usage of foreign investment is the sectoral balances identity where one forgets the government deficits and writes I – S = M – X and concludes that imports are due to “foreign investment” or something of that sort. Foreign direct investment may be helpful but the decision to import is due to the volitional decisions of a citizens of a nation to choose a foreign product over a domestic one. Not sure if there is huge amount of FDIs happening in the US. The imports just leave foreigners with some money to purchase financial assets and gives them income in perpetuity. This does nothing to increase productivity.

Can you expand on the usage of economic versus financial ?

Ramanan,

I do not say that imports are due to foreign investment although there can be an association if this investment brings imported real resources. However, import demand can attract foreign investment and also lead to rising domestic productive capacity.

The point is that the effective constraint for fiscal policy, regardless of the monetary regime, is the availability of real resources and productive capacity and the foreign sector can be a strategic input for adding real capacity in an economy with the structural imbalances I have mentioned in my previous comment. Notice that fiscal policy can have an acceleration effect upon potential output/income and fiscal capacity can rise. The revenue or financial constraint upon fiscal policy becomes relevant in economies with no seignorage power of fiat currency and in the absence of flexible exchange rates there is one more constraint on fiscal policy. Even with flexible exhange rates public debt denominated in foreign unit of account, regardless who owns it can represent a constraint. This is the case as long as the real resources/productive capacity boundary is limited by the unavailability of foreign resources at any exchange rate purchased by the domestic currency and the interest cost in foreign currency debt cannot be supported by an equivalent inflow of foreign reserves due to exports and capital inflows.

Panayotis,

Agreed that fixed exchange rate regimes are troublesome and that flexible one is more flexible.

I am pointing out to the constraints nations face due to the external world, fixed or floating. And the aim is to point out how the games nations play lead to worse outcomes.

Panayotis: In particular with respect to real constraints, I am interested in learning about the trashing of productive capacity due to increasing unemployment that accompanies current account deficits. Yes employment guarantee will work but in my opinion creating an employment guarantee in an unbalanced economy will only worsen the problems.

“employment guarantee will work but in my opinion creating an employment guarantee in an unbalanced economy will only worsen the problems.”

Thats an extreme position. Sure you know what you are writing ?

Vinodh,

I am not sure what you are asking me. Please explain your hypothesis so I could be able to respond if possible.