I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Do current account deficits matter?

I have noticed a few commentators expressing concern about the dangers that might arise if a nation runs a persistent current account deficit. There have been suggestions that this area of analysis is the Achilles heel of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). I beg to differ. A foundation principle of MMT is that to be able to freely focus on the domestic economy, the national government has to be freed from targetting any external goals – such as a particular exchange rate parity. The only effective way for this to happen is if the exchange rate floats freely. In this sense, the exchange rate is the adjustment mechanism for external imbalances.

MMT is built on the foundation that the national government is a monopoly issuer of its own currency and is never revenue constrained. That means it can buy whatever is available for sale in that currency at any time of its choosing. Whether it is prudent to do that at any point in time is another matter and has to be considered on a case by case basis (depending what else is going on in the economy).

However, the fact it faces no financial constraints is not a sufficient condition for a sovereign government being able to advance public purpose. The latter goal relates to maximising domestic outcomes including environmentally-sustainable growth, low unemployment, real wages growth in line with productivity, and inclusive social policies.

To be able to freely focus on the domestic economy, the national government has to be freed from targetting any external goals – such as a particular exchange rate parity. The only effective way for this to happen is if the exchange rate floats freely.

To appreciate that point consider how a fixed exchange rate system operated.

Fixed exchange rates

The Bretton Woods System was introduced in 1946 and created the fixed exchange rates system. Governments could now sell gold to the United States treasury at the price of $USD35 per ounce. So now a country would build up USD reserves and if they were running a trade deficit they could swap their own currency for USD (drawing from their reserves) and then for their own currency and stimulate the economy (to increase imports and reduce the trade deficit).

The fixed exchange rate system however rendered fiscal policy relatively restricted because monetary policy had to target the exchange parity. If the exchange rate was under attack (perhaps because of a balance of payments deficit) which would manifest as an excess supply of the currency in the foreign exchange markets, then the central bank had to intervene and buy up the local currency with its reserves of foreign currency (principally $USDs).

This meant that the domestic economy would contract (as the money supply fell) and unemployment would rise. Further, the stock of $USD reserves held by any particular bank was finite and so countries with weak trading positions were always subject to a recessionary bias in order to defend the agreed exchange parities. The system was politically difficult to maintain because of the social instability arising from unemployment.

So if fiscal policy was used too aggressively to reduce unemployment, it would invoke a monetary contraction to defend the exchange rate as imports rose in response to the rising national income levels engendered by the fiscal expansion. Ultimately, the primacy of monetary policy ruled because countries were bound by the Bretton Woods agreement to maintain the exchange rate parities. They could revalue or devalue (once off realignments) but this was frowned upon and not common.

This period was characterised by the so-called “stop-go” growth where fiscal policy would stimulate the domestic economy, drive up imports, put pressure on the exchange rate, which would necessitate a monetary contraction and stifle economic growth.

Whichever monetary system of those that have been tried in the past – pure gold standard or USD-convertible system backed by gold – the constraints on the ability of government to advance public purpose were obvious.

The gold standard as applied domestically meant that existing gold reserves controlled the domestic money supply. Given gold was in finite supply (and no new discoveries had been made for years), it was considered to provide a stable monetary system. But when the supply of gold changed (a new field discovered) then this would create inflation.

So gold reserves restricted the expansion of bank reserves and the supply of high powered money (Government currency). The central bank thus could not expand their liabilities beyond their gold reserves (although it is a bit more complex than that). In operational terms this means that once the threshold was reached, then the monetary authority could not buy any government debt or provide loans to its member banks.

As a consequence, bank reserves were limited and if the public wanted to hold more currency then the reserves would contract. This state defined the money supply threshold.

Some gymnastics could be done to adjust the quantity of gold that had to be held. But overall the restrictions were solid.

The concept of (and the term) monetisation comes from this period. When the government acquired new gold (say by purchasing some from a gold mining firm) they could create new money. The process was that the government would order some gold and sign a cheque for the delivery. This cheque is deposited by the miner in their bank. The bank then would exchange this cheque with the central bank in return for added reserves. The central bank then accounts for this by reducing the government account at the bank. So the government’s loss is the commercial banks reserve gain.

The other implication of this system is that the national government can only increase the money supply by acquiring more gold. Any other expenditure that the government makes would have to be “financed” by taxation or by debt issuance. The government cannot just credit a commercial bank account under this system to expand its net spending independent of its source of finance. As a consequence, whenever the government spent it would require offsetting revenue in the form of taxes or borrowed funds.

Ultimately, Bretton Woods collapsed in 1971. It was under pressure in the 1960s with a series of “competitive devaluations” by the UK and other countries who were facing chronically high unemployment due to persistent trading problems. Ultimately, the system collapsed because Nixon’s prosecution of the Vietnam war forced him to suspend USD convertibility to allow him to net spend more. This was the final break in the links between a commodity that had intrinsic value and the nominal currencies. From this point in, governments used fiat currency as the basis of the monetary system.

As I have written in the past, elaborate institutional mechanisms have survived the collapse of the convertible currency system which make it look as if the government is funding its net spending by bond issues. The reality is that in a fiat currency system all the government is doing when it issues debt is draining reserves which it has created itself. I use the term – “its a wash”. The government really just borrows back what it has spent.

The important point is that the imposition of fixed exchange rates constrained the capacity of the government to pursue public purpose.

Flexible exchange rates

Many progressives think that flexible exchange rates is a neo-liberal policy because it was fiercely advocated by Milton Friedman during the 1960s. His advocacy for flexible rates was based on his view that all prices should be fully flexible so that markets can work. MMT advocates flexible exchange rates because it is the only way that the macroeconomic policy tools (fiscal and monetary) can be totally free to pursue domestic policy agendas. They do not become compromised by the need to defend a parity.

If progressives really understood this point they would be on much more solid ground when they argue for “Keynesian-style” expansionary policies.

The flexible exchange rate system means that monetary policy is freed from defending some fixed parity and thus fiscal policy can solely target the spending gap to maintain high levels of employment and other desirable policy objectives. The foreign adjustment is then accomplished by the daily variations in the exchange rate.

Please read my blog – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail – for more discussion on the differences between monetary systems.

Under flexible exchange rates, the sovereign government has more domestic policy space than the mainstream economists acknowledge. The government can make use of this space to pursue economic growth and rising living standards even if this means expansion of the Current Account deficit (CAD) and depreciation of the currency.

While there is no such thing as a balance of payments growth constraint in a flexible exchange economy in the same way as exists in a fixed exchange rate world, the external balance still has implications for foreign reserve holdings via the level of external debt held by the public and private sector.

It is also advisable that a nation facing continual CADs foster conditions that will reduce its dependence on imports. However, the mainstream solution to a CAD will actually make this more difficult.

Indeed, IMF lending and the accompanying conditions that are typically imposed on the debtor nation almost always reduce the capacity of the government to engineer a solution to the problems of inflation and falling foreign currency reserves without increasing the unemployed buffer stock. A policy strategy based largely on fiscal austerity will create unacceptable levels of socio-economic hardship.

Targets to reduce budget deficits may help lower inflation, but only because the “fiscal drag” acts as a deflationary mechanism that forces the economy to operate under conditions of excess capacity and unemployment.

This type of deflationary strategy does not build productive capacity and the related supporting infrastructure and offers no “growth solution”. And fiscal restraint may not be successful in lowering budget deficits for the simple reason that tax revenue can fall as the taxable base shrinks because economic activity is curtailed.

Moreover, the lessons of how the international crises of the 1990s and early 2000s were dealt with should not be forgotten: fiscal discipline has not helped developing countries to deal with financial crises, unemployment, or poverty even if they have reduced inflation pressures.

There are also inherent conflicts between maintaining a strong currency and promoting exports – a conflict that can only be temporarily resolved by reducing domestic wages, often through fiscal and monetary austerity measures that keep unemployment high. The best way to stabilise the exchange rate is to build sustainable growth through high employment with stable prices and appropriate productivity improvements.

A low wage, export-led growth strategy sacrifices domestic policy independence to the exchange rate – a policy stance that at best favours a small segment of the population.

Is a current account deficit a problem?

We continually read that nations with current account deficits (CAD) are living beyond their means and are being bailed out by foreign savings. This claim is particularly potent in the current US-China context.

In MMT, this sort of claim would never make any sense. A CAD can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the CAD. This desire leads the foreign country (whichever it is) to deprive their own citizens of the use of their own resources (goods and services) and net ship them to the country that has the CAD, which, in turn, enjoys a net benefit (imports greater than exports). A CAD means that real benefits (imports) exceed real costs (exports) for the nation in question.

There are complications where one currency (USD) is a reserve currency widely used throughout the world in resolving trade. But ultimately, this is only a complication.

A CAD signifies the willingness of the citizens to “finance” the local currency saving desires of the foreign sector. MMT thus turns the mainstream logic (foreigners finance our CAD) on its head in recognition of the true nature of exports and imports (see below).

Subsequently, a CAD will persist (expand and contract) as long as the foreign sector desires to accumulate local currency-denominated assets. When they lose that desire, the CAD gets squeezed down to zero. This might be painful to a nation that has grown accustomed to enjoying the excess of imports over exports. It might also happen relatively quickly. But at least we should understand why it is happening.

Sterilisation enters the scene here as well. It is often erroneously thought that financial inflows (corresponding to the CAD) via the capital account of the Balance of Payments boost commercial bank reserves. Mainstream economists who operate within the defunct money multiplier paradigm think this might be inflationary because it will stimulate bank credit creation.

The flawed logic is – increased bank reserves -> increased capacity to lend -> increased credit -> excess aggregate demand -> inflation.

You might like to read the following blogs – Money multiplier and other myths – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – to understand why that is totally at odds with the way the credit creation system operates.

The claim is that the central bank can “sterilise” this impact by selling government debt via open market operations. However, if there is excess capacity in the economy, the central bank might refrain from sterilising and allow aggregate demand to expand.

But think about what a CAD actually means. I always argue that it is essential to understand the relationship between the government and non-government sector first. A common retort is that this blurs the private domestic and foreign sectors. My comeback is that the transactions within the non-government sector are largely distributional, which doesn’t make them unimportant, but which means you don’t learn anything new about the process net financial asset creation.

In the case of CAD, what mostly happens is that local currency bank deposits held say by Australians are transferred into local currency bank deposits held by foreigners. If the Australian and the foreigner use the same bank, then the reserves will not even move banks – a transfer occurs between the Australian’s account in say Sydney, to the foreigner’s account with the same bank in say Frankfurt.

The point is that the AUD never leaves “Australia” no matter who is holding it. The same goes for the USD and all the fiat currencies.

If the transactions span different banks, the central bank just debits and credits, respectively, the reserve accounts of the two banks and the reserves move.

What happens next depends on the approach the commercial banks take to the reserve positions. We know that excess reserves put downwards pressure on overnight interest rates and may compromise the rate targetted by the central bank. The only way the central bank can maintain control over its target rate and curtain the interbank competition over reserve positions is to offer an interest-bearing financial asset to the banking system (government debt instrument) and thus drain the excess reserves.

So sterilisation in this case merely reflects the desire of the central bank to maintain a particular target interest rate and is not discretionary. The alternative is to offer a return on excess returns equivalent to the target rate.

Should CADs be prevented?

The other implication of the mainstream view is that policy should be focused on eliminating CADs. This would be an unwise strategy.

First, it must be remembered that for an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Net imports means that a nation gets to enjoy a higher living standard by consuming more goods and services than it produces for foreign consumption.

Further, even if a growing trade deficit is accompanied by currency depreciation, the real terms of trade are moving in favour of the trade deficit nation (its net imports are growing so that it is exporting relatively fewer goods relative to its imports).

Second, CADs reflect underlying economic trends, which may be desirable (and therefore not necessarily bad) for a country at a particular point in time. For example, in a nation building phase, countries with insufficient capital equipment must typically run large trade deficits to ensure they gain access to best-practice technology which underpins the development of productive capacity.

A current account deficit reflects the fact that a country is building up liabilities to the rest of the world that are reflected in flows in the financial account. While it is commonly believed that these must eventually be paid back, this is obviously false.

As the global economy grows, there is no reason to believe that the rest of the world’s desire to diversify portfolios will not mean continued accumulation of claims on any particular country. As long as a nation continues to develop and offers a sufficiently stable economic and political environment so that the rest of the world expects it to continue to service its debts, its assets will remain in demand.

However, if a country’s spending pattern yields no long-term productive gains, then its ability to service debt might come into question.

Therefore, the key is whether the private sector and external account deficits are associated with productive investments that increase ability to service the associated debt. Roughly speaking, this means that growth of GNP and national income exceeds the interest rate (and other debt service costs) that the country has to pay on its foreign-held liabilities. Here we need to distinguish between private sector debts and government debts.

The national government can always service its debts so long as these are denominated in domestic currency. In the case of national government debt it makes no significant difference for solvency whether the debt is held domestically or by foreign holders because it is serviced in the same manner in either case – by crediting bank accounts.

In the case of private sector debt, this must be serviced out of income, asset sales, or by further borrowing. This is why long-term servicing is enhanced by productive investments and by keeping the interest rate below the overall growth rate. These are rough but useful guides.

Note, however, that private sector debts are always subject to default risk – and should they be used to fund unwise investments, or if the interest rate is too high, private bankruptcies are the “market solution”.

Only if the domestic government intervenes to take on the private sector debts does this then become a government problem. Again, however, so long as the debts are in domestic currency (and even if they are not, government can impose this condition before it takes over private debts), government can always service all domestic currency debt.

How do deficits and the external sector interact?

MMT shows that fiscal deficits result in net injections of banking system reserves that due to common (voluntarily imposed) arrangements are drained through sales of government debt either in the new issue market (by Treasury) or through open market sales (by the central bank).

If these (unnecessary) voluntary arrangements which force governments to match $-for-$ their net spending with bond sales were abandoned then the central bank would start accumulating treasury assets (maybe via formal bond sales but more sensibly via some numbers in an accounting ledger to keep record of the transactions).

International financial markets would immediately (and erroneously) believe that this accumulation of represents “monetisation of the deficit”, and that this contributes to inflationary pressures, although the empirical evidence is scant. Some selling off of the currency might occur as a consequence of investors forming this expectation.

If there is inflationary pressure, it would result from the government spending, not from the bond sales that drain excess reserves.

Problems are greatly compounded if the nation has issued foreign-currency denominated debt. If this debt is issued by private firms (or households), then they must earn foreign currency (or borrow it) to service debt. To meet these needs they can export, attract FDI, and/or engage in short-term borrowing. If none of these are sufficient, default becomes necessary.

There is always a risk of default by private entities, and this is a “market-based” resolution of the problem as noted above.

If however the government has issued (or taken over) foreign currency denominated debt, default becomes more difficult because there is no well delineated international method. Often, the government is forced to go to international lenders to obtain foreign reserves; the result can be a vicious cycle of indebtedness and borrowing.

Since international lenders request austerity, domestic policy becomes hostage. For this reason, it is almost always poor strategy for government to become indebted in foreign currency. By contrast, a sovereign government can never face insolvency in its own currency.

What would happen if the government issued no debt?

When it credits the bank account of any recipient of its spending (whether this is for purchases of goods and services or for social welfare spending), the central bank simultaneously credits the bank’s reserve account. If this leads to excess reserves, these are then exchanged for treasury debt. While the IMF and other mainstream financial analysts criticise sales of treasury debt to the central bank (or corresponding accounting entries), it actually makes no difference whether treasury sells the debt to private banks. In effect the sales directly to the central bank simply bypass the bank “middlemen”.

If you think there is a difference between treasury debt being sold the central bank or to the commercial banks then you do not understand reserve accounting which is at the heart of MMT.

The reality is that the end result will be the same: the distribution of treasury debt holdings between the central bank and the private sector will depend on portfolio preferences of the private sector. These preferences are reflected in upward or downward pressure on the overnight interest rate. To hit its target, the central bank must accommodate private sector preferences by either taking the debt into its portfolio, or by selling the debt to reduce bank reserves.

The only complication is that the treasury can issue debt of different maturities. Very short-term treasury debt is equivalent to bank reserves that earn interest. Long term treasury debt is not a perfect substitute because capital gains and losses can result from changes to interest rates.

Hence if there is a lot of uncertainty about the future course of interest rates, trying to sell long-term treasury debt to private markets can affect interest rates and the term structure. For example, selling long-term debt that is not desired by the private sector will lead to low prices and high interest rates for that debt. In this case, it is not really the case that budget deficits are affecting interest rates, but rather the decision to sell debt with a maturity that is not desired by markets. The solution would be to limit treasury debt to short-term maturity.

An important point to be made regarding treasury operations by a sovereign government is that the interest rate paid on treasury securities is not subject to normal “market forces”. The sovereign government only sells securities in order to drain excess reserves to hit its interest rate target. It could always choose to simply leave excess reserves in the banking system, in which case the overnight rate would fall toward zero or whatever support rate on reserves was being offered.

When the overnight rate is zero, the Treasury can always offer to sell securities that pay a few basis points above zero and will find willing buyers because such securities offer a better return than the alternative (zero).

This drives home the point that a sovereign government with a floating currency can issue securities at any rate it desires – normally a few basis points above the overnight interest rate target it has set.

There may well be economic or political reasons for keeping the overnight rate above zero (which means the interest rate paid on securities will also be above zero). But it is simply false reasoning that leads to the belief that the size of a sovereign government deficit affects the interest rate paid on securities.

When the central bank desires to target a non-zero interest rate, budget deficits will thus lead to growing debt and increased interest payments. However, the interest rate is a policy variable for any sovereign nation which can increase its deficits and its outstanding debt while simultaneously lowering its interest payments by lowering interest rates.

A non-sovereign government faces an entirely different situation. In the case of a “dollarised” nation, the government must obtain dollars before it can spend them. Hence, it uses taxes and issues IOUs to obtain dollars in anticipation of spending.

Unlike the case of a sovereign nation, this government must have “money in the bank” (dollars) before it can spend. Further, its IOUs are necessarily denominated in dollars, which it must incur to service its debt. In contrast to the sovereign nation, the non-sovereign government promises to deliver third party IOUs (that is, dollars) to service its own debt (while the US and other sovereign nations promise only to deliver their own IOUs).

Furthermore, the interest rate on the non-sovereign, dollarised government’s liabilities is not independently set. Since it is borrowing in a foreign currency, the rate it pays is determined by two factors. First there is the base rate on the foreign currency. Second, is the market’s assessment of the non-sovereign government’s credit worthiness. A large number of factors may go into determining this assessment. The important point, however, is that the non-sovereign government, as user (not issuer) of a currency cannot exogenously set the interest rate. Rather, market forces determine the interest rate at which it borrows.

Other considerations

One commentator recently wrote:

However, the external sector has other dollar-denominated assets as well such as equities, corporate bonds and mortgage backed securities and the question is what about the rates with which such numbers grow? If a stock is held by a household, the dividend goes to it and the household may consume a part of it and it flows back to the producer. If the external sector holds the stock, it just goes to it and doesn’t flow back to the domestic sector. The US government can increase its fiscal stance but what if all the expansion goes to the external sector? In other words, there is a scenario in which the fiscal expansion improves short term demand, but doesn’t do much in the long term (for countries such as the US with a huge external debt, though denominated in the local currency).

First, the dollars never leave the country. Yes, an external holder of a USD income stream can use that stream to purchase goods and services elsewhere given the reserve status of the USD. But what is the problem? Ultimately, the holder of the USD can only realise these holdings by buying goods and services (or assets) denominated in US dollars.

Second, the advantage of fiscal policy is that it can be targetted to alter the composition of output as well as the level of output. So one of the first policies I advocate is the introduction of a Job Guarantee which would focus the public spending on the domestic economy and deliver domestic (non-tradeable) outputs. It is very hard to see a high proportion of this expansion going out of the country.

Third, more generally, the government can always buy what is for sale in its own currency. Every country has a well-developed non-tradeables sector which offers many goods and services that can be procured for the advancement of public purpose. Why would we be concerned if the government improves mental health care by increasing the educational outlays for these professions and employing increasing numbers of the graduates? Perhaps, the new workers will buy some imports. What exactly is the problem?

Fourth, all private sector decisions are made on a voluntary basis with the best knowledge that is available. If private firms are selling financial claims to foreigners they are doing this voluntarily. What is the problem? It just means the external leakage is greater and there is more space for domestically-orientated injections, without compromising the stable price objective.

The same commentator then noted:

If the dollar devalues because of market forces, the position of various domestic sectors of the US improves because the values of their external assets increases. They export more as well and this increases demand as well. However, the US dollar has been artificially high or one can say that the others have pegged theirs to lower values. The manufacturers in the US have great production capacity and products, are competitive and have good selling skills. In spite of this, manufacturing has weakened a lot in the US. The answer to why this has happened may only be in the monetary economics related to the external sector. One can say that the US government should have just increased the fiscal deficit but that would have increased the trade deficit – who wins the race ?

First, while there is some debate about the value of the import and export price elasticities, it is generally believed that a depreciating currency does have the impacts you mention. Competitiveness is enhanced without a harsh austerity drive to drive down domestic wages. This is the mechanism the EMU nations are sorely missing at the moment (among others). This stimulates exports (usually but not always) and reduces imports.

Is that a good thing? Not in itself because exports impose costs and imports provide benefits. But it may be that the aggregate demand injection boosts local jobs which is a good outcome. All these judgements depend on what happens.

Second, it is clear that China is buying US financial assets and this is having the effect of keeping their currency weak. Although recently they have let the currency follow a peg (and appreciate a little). But the Chinese can hardly liquidate its holdings of foreign currencies because then they would strengthen their own currency and undermine their own trade plan.

So their option is to buy US dollar-denominated financial or other assets to keep their own currencies weak and maintain their export competitiveness. All they are doing is depriving their own citizens of development opportunities.

Third, it is clear that the US dollar remains the safe haven and this has impacts on the competitiveness of its manufacturing sector. But that has nothing much to do with the effectiveness of the public deficits nor of the current account that the US is running. It has to do with the relative attractiveness of other currencies, most recently the Euro.

Fourth, the statement “The manufacturers in the US have great production capacity and products, are competitive and have good selling skills. In spite of this, manufacturing has weakened a lot in the US” is counter to the facts. If they were competitive (by which we mean internationally competitive) then they wouldn’t be losing market share.

The logic of the market is that consumers will demand what they think is best. It is clear that they no longer think US production fits that category. That might be heart-wrenching for the dying manufacturing towns – as it was as agriculture waned some decades earlier and communities vanished – but I doubt that you want to argue for protection where the rest of the US consumers subsidise the jobs of a few who can no longer produce attractive enough products in their own right.

Further, while manufacturing in the US has declined (as it has in most advanced nations), the high productivity manufacturing jobs have stayed in the US. The low wage jobs have been exported to China, India and elsewhere.

Finally, I don’t think this has anything to do with the effectiveness of fiscal policy.

Australia

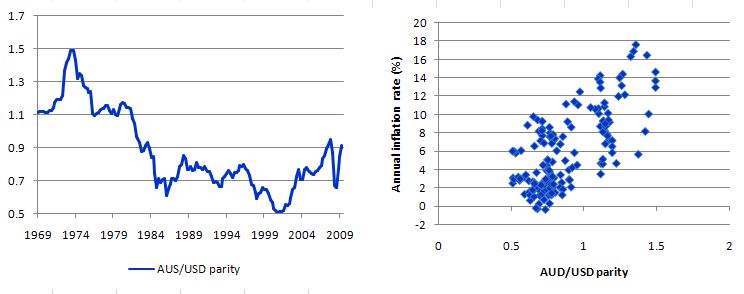

The following graph is taken from the RBA statistics and shows in the left-panel the AUS/USD exchange rate since 1969 and in the right-panel the relationship between the exchange rate (horizontal axis) and annual inflation rate (vertical axis).

The left-panel shows you how much of a roller coaster the Australian economy is on with respect to its exchange rate. Within a decade it has gone from below 50 cents USD to nearly parity. The sky hasn’t fallen in.

The right panel shows that there is no intrinsic relationship between domestic inflation and the exchange rate. If anything it is the reverse of that which the fear mongers claims exists.

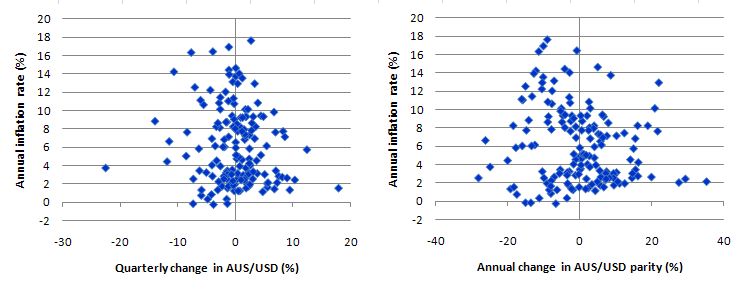

For those who think the change in the exchange rate matters, the following graph demonstrates that it doesn’t. Quarterly changes in the left-panel and annual in the right-panel.

Conclusion

That is enough for today!

You’re looking at the wrong thing. The problem isn’t caused by the exchange rate itself, but by the rate of change of the exchange rate.

Dear Aidan

Just for you – I updated the graphs. There is no problem.

best wishes

bill

Great article that answers a lot of questions, however the elephant in the room here is still ‘oil’. Everywhere except the US is petrified of currency devaluation in case they delivered an oil shock to their economies.

Bill, it’s amazing to see how an open platform like yours can maintain such high standards. The fact that you respond and incorporate some of the more demanding and intelligent arguments proves not only that you are a good teacher but that this truly is a community, as panayotis said the other day. It makes the reading experience for the more passive members like myself all the more rewarding. Thank you!

Bill, it’s amazing to see how an open platform like yours can maintain such high standards (I obviously can’t see the hate mail you fend off behind the scenes). The fact that you respond to and incorporate some of the more demanding and intelligent arguments from the comments section proves not only that you are a good teacher but that this truly is a community, as Panayotis said the other day. It also makes the reading experience for the more passive / amateur ‘members’ like myself all the more rewarding. Thank you!

Dear Bill

I haven’t written to you before. So first a couple of lines as background. I retired 2 years ago from a technical job here in UK. I have no economics training but have always been interested.

I have been trying to understand economics to understand the recent crisis and the proposed measures to get us out of the fix we are in. Not succeeded yet, but delighted to find your blog about 2 weeks ago; brightens the day up! It is enlightening that there are alternatives to the sackcloth and ashes we are about to have heaped on us. I hadn’t heard of MMT, so am trying to read and learn about it.

First, about your latest blog. I don’t understand why you concentrated on Current Account Deficit. If you had written Trade Deficit, all would be clear to me. I had understood that MMT really didn’t worry too much about CAD provided the economy etc was not overheating etc. Can you help please?

The blog helps with one major area of doubt / lack of understanding I have, but I can not yet really understand what the economic control measures are within MMT. It seems to me that there is a need to understand the total output from an economy in some absolute way so that countries know how near to the inflationary edge they are. Have you written about this anywhere else, please? I have this horrible feeling that I am missing something obvious!

The other thing I am looking for with MMT is how one country like Australia or UK could follow the type of economic policies you and your colleagues advocate in a world where everyone else follows different economic theories and control all the economic levers. So put simply, what is the route map to get from where we are now to some countries following MMT principles in controlling their economy? Can we have mixed bathing, or will those that try to follow MMT whilst all the others continue as now result in the pioneers getting stripped naked!

Perhaps I am so new to this that I just don’t understand yet, but any help or guidance you can give would be great.

Thanks

Richard

PS I have many other queries, but I think I should keep this initial query short.

You’ve covered a lot of ground that’s been quaking recently.

One suggestion: in the discussion of government bonds generally, you might do a blog that specifically contrasts the nature of bond pricing under an MMT zero natural rate environment, versus an active interest rate management monetary policy. Expectations for future monetary policy are a significant pricing factor in the latter. I found the “few basis points more” discussion a little ambiguous in that sense.

Again very interesting read! Guess Bill with his take on CA and Import/Export is banned from speaking in public in Germany? Speaking so would cause riots and clearly pose an acute danger to public order.

I’ve also some other question to commenter. Some years ago I read Steven Landsburg’s “Armchair Economist” and enjoyed it. So since he is also blogging by now I’m following his blog. In his latest post leaving aside his childish ad hominem attacks on Paul Krugman he writes:

Thanks to Bill’s relentless educational efforts it takes now only nano seconds to identify utter nonsense. My question: do you engage with such erroneous thinking via comment or simply ignore it as some sort of incurable brain conditioning? What’s your take?

“So gold reserves restricted the expansion of bank reserves and the supply of high powered money (Government currency). The central bank thus could not expand their liabilities beyond their gold reserves (although it is a bit more complex than that).”

I’ve been looking for an explanation of the “although” part for some time now. Haven’t seen it anywhere. And wonder if anybody actually knows.

Bill –

Thanks for the extra graphs. Looking at the upper part of the annual change one, there does appear to be a trend of inflation being higher the more the Australian dollar devalues against the US dollar (and lower when our dollar rises). But there’s no clear trend in the lower part of the graph.

And thinking about it a bit, that’s not really surprising. A declining dollar is likely to increase the price of imports and commodities, so increasing inflation. But the policy of inflation targetting means that it hasn’t had the opportunity to have that effect recently. Instead we’d get higher interest rates. These would negatively impact economic growth, so I can’t agree with your conclusion that there is no problem.

Time issues in writing a detailed comment on the interesting post.

Anon:

I believe the money supply was not exogenous in the gold standard. Money cannot but be endogenous. Rather, the recessionary environment would happen because of “fiscal policy reaction function” and/or “monetary policy reaction function”.

Lets say settlement happens instantaneously. An import reduces reserves and gold from banks’ and central banks’ assets (respectively), but will be compensated by increase in the items “claims on banks” on the central bank assets and the reserves come back to the original. This is in overdraft economies. In asset-based economies, the central bank would purchase government debt to bring the reserves back to the original.

For surplus countries, banks’ indebtedness to the central bank would reduce.

I agree with Oliver above. Thanks Bill.

On another note, did anyone else see the budget released by the UK today? Truly scary IMO. I cannot figure out how people in such positions of authority can be so seemingly clueless.

Ramanan,

I deplore the use of the word “endogenous”.

He he Anon – even I was put off initially by the word “endogenous” or “endogeneity”. I understand it as “not fixed” or opposite of exogenous. The usual theory is that the central bank sets the money supply and so the money supply curve (rates on y-axis and supply on x-axis) is vertical. The interest rate is the point where the downward sloping demand curve (for money) would meet this vertical supply curve. And hence in this picture, interest rates are endogenous 🙂

Re Aidan

“Looking at the upper part of the annual change one, there does appear to be a trend of inflation being higher the more the Australian dollar devalues against the US dollar (and lower when our dollar rises).”

By eye, you are right, and your reasoning as to why may well be correct, but consider the standard deviation shown – its enormous. There’s some weak correlation, but not a lot so there must be other strong factors

Re Greg – Yes, I live in UK! H E L P!!!

Richard

“It is often erroneously thought that financial inflows (corresponding to the CAD) via the capital account of the Balance of Payments boost commercial bank reserves.”

I’ve always been a little unclear on the specifics of why the capital account must equal the current account. I certainly get the algebra (Balance of Payments = Current Account – Capital Account), but I don’t clearly understand the mechanism through which the two terms come into balance. It is my understanding that the Capital Account is equal to the net change in financial flows entering/leaving a country. So it is comprised of things like foreign direct investment (long term capital investment/disinvestment such as the purchase or construction of machinery, buildings or even whole manufacturing plants), portfolio investment (buying/selling of shares and bonds), and most important of all changes in foreign reserves held by a nation’s central bank. My question is why should a nation importing more than it is exporting (a current account deficit) necessarily lead to a corresponding increase in financial flows entering that nation (or vice-versa for a current account surplus)? When a nation runs a current account deficit it experiences a net-outflow of financial assets and in exchange receives a net inflow of real goods and services. To me this doesn’t seem to be connected to the financial flows of that nation’s trading partner(s). To take China and the U.S. for example: when the U.S. imports more than it exports it transfers dollars to China and China ships real goods and services in exchange back to the U.S. Why should China then have to transfer an equal number of Yuan back to the U.S. as foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, etc…? Is that not what the balance between the Current Account and the Capital Account implies? It seems to me that these should be two separate and independent processes. If someone has the time could he/she please try to briefly explain this relationship to me. Thank you.

Richard –

Of course there are other stronger factors. Currency devaluation is one of three components of inflation, the others being cost push and demand pull.

Australia is a big (and comparatively remote) country, so the proportion of domestic trade is very high. And it relies heavily on exporting commodities, so commodity prices often make more difference than currency rates. But that doesn’t mean currency rates are unimportant – it merely means they’re one of many important variables.

NKlein1553,

If the US pays China one dollar for imported goods (current account), that dollar ends up being China’s claim (asset) on the US banking system (liability). That claim is recorded as a capital inflow into the US. It’s an automatic micro banking system accounting entry and an automatic macro accounting classification.

The dollar outflow from the US is on current account; the mirror image dollar inflow to the US is on capital account.

Ramanan,

My impression is that mainstream economics uses these words in a generic sense wherever possible. There must be something deeply flawed with a system of thought that employs such vagueness so lavishly.

🙂

Thank you anon, that was certainly succinct. I think I understand your explanation, but I guess it’s just because I’ve never taken an accounting class that the terminology seems a little strange to me. A liability is a claim someone or some institution must pay out over a set period of time. Investopedia defines liability as: “A company’s legal debts or obligations that arise during the course of business operations. These are settled over time through the transfer of economic benefits including money, goods or services.” So it seems a little counter-intuitive to me that claims on the U.S. banking system (for example, the dollars China accumulates through its current account surplus) should be recorded as as a capital inflow. I’m going to have to let your explanation sink in a little. Thanks again for your help.

I can see how the importing country gets a benefit of lower-cost goods, but what about the lost jobs which have gone overseas to allow for the exporting country to produce those goods?

I understand that “dollars don’t leave the country” and fairly comfortable with monetary operations here are a few things I have to say to our host and other commentators:

Imagine a group of people forming an island and wishing to trade with the rest of the world. The international currency markets will not accept the currency unless these islanders show trade surpluses. The international currency markets possess tremendous powers to punish a country. While the state is bigger than the bond markets, it is not bigger than the currency markets. Many times, the movement is drastic and a currency can plunge causing major shocks.

The gold standard never followed the rules of the game – in other words, the Mundell-Fleming approach was inapplicable in the Gold-Standard era. Central banks had reasonable sized assets in their balance sheets other than gold – for example, claims on banks and/or government securities. A current account deficit wouldn’t reduce the reserves as per my comment @22:57.

I don’t mind the usage of the terminology debt monetization and neither does Anon mind. As long as we recognize that it doesn’t make a bank’s customers more credit-worthy, the usage is okay. Its even legal. If a central bank agrees to purchase government bonds directly, such things are documented. So it has an ontology. If one wishes to combine the balance sheets of the central bank and the government, then it appears funny.

In the gold-standard, the international payments would settle in gold. This doesn’t reduce the reserves – but the central bank and the government, under the pressure of losing more gold would go into an austerity mode in order to stop further outflow. Interest rates would rise but that is the discretionary action of the central bank – the central bank reaction function, not some automatic phenomenon.

The current account deficits were problematic because, there is a “hard thing” that a nation could lose and faced by the prospects of not being able to do international trade it would go into an austerity mode. Its a complex world, and the result could be anything including improvement of the current account. The nations also had the option of devaluation and this would put pressure on imports and improve exports – at least in theory. There are/were other advantages – the devaluation and high interest rates may bring in capital inflows because the investors may be willing to bet on an improvement and make gains through higher interest paid as well as possibilities of gains because of a possible future revaluation. The nation under pressure may feel less stressed because the capital inflow brings gold inflows and has bought time.

The central bank reaction function may have a money target, but the reaction function can also have money targets in the fiat world – and the citizens can suffer the scourge of monetarism even in fiat currencies.

There is another institutional setup where reserves can change because of capital inflow – the Euro Zone. It is true that the total reserves of banks of all countries is constant, it may not be true of a single country. To complicate matter, the Euro Zone is an overdraft type, the “sterilization” is automatic. Banks of countries with excess reserves automatically reduce their indebtedness to their NCBs – no operations are needed.

What a funny word sterilization is! A neoclassical invented word – its used to denote that in the absence, there will be some sort of money multiplication! In a fiat currency like that of China, capital inflow indeed increases reserves but not directly. It increases because the central bank purchases foreign currency and pays in reserves. Yes, the sterilization is really an interest rate maintenance operation.

Now I come to the current account deficits. An importer settles in bank money. The exporter may sell it to his local bank and the bank may purchase the government debt of the country in deficit. Or the bank can purchase other securities or sell it to a financial intermediary who may purchase some security of the deficit country. The bank may also sell the currency to its central bank and the central bank is most likely to purchase government debt. Yes of course no dollars leave the US!

Several things can be said. The import was a volitional decision of the importer. When the importer imports, its lost income for a domestic producer. In this hand-waving way of saying things, imports reduce national income. There are other ways to show this as well but sufficient to say at this point that unless the government compensates this, national income is inversely proportional to the propensity to import. It is true that budget deficits are endogenous, but for a fiscal stance, there is nothing automatic to bring the employment back to the original level. Ceteris paribus imports increase unemployment

There are many situation that can be analyzed when ceteris is not paribus. I will analyze them in the next comment.

“In this hand-waving way of saying things, imports reduce national income.”

Really?

Maybe in terms of a “lost opportunity”, which is conjecture, but not in terms of fact of trade.

The second term in (EX – IM) does not represent a loss of income.

It’s just an elimination of what otherwise would be double counting of income in the GDP equation.

What you can say is that imports reduce (net) financial assets of the importing country.

But that’s not the same as income.

Anon,

Yes, from the identity, its difficult to figure out the national income. But one way to think is that X -M occurs with G – T and net exports acts a bit like the budget deficit.

Continuing …

While I understand that there is no financial constraint and that no dollars leave etc., an analogy can be given. Imports are like bleeding and national income and expenditure and be thought of as a flow of blood. Saying that current account deficit is okay and sustainable is like saying that since someone provides an infinite supply of blood, bleeding is not a problem. The fact can imports “go to” the external sector is not problematic because there is no lack of funds or money but with the analogy, not importing is like keeping the circulation inside the body in a good condition.

Several scenarios can be analyzed when the ceteris is not paribus as per my comment @3:17.

The fiscal policy is two variables – the government spending G and the tax rate t. It can be combined into one number G/t. The ceteris paribus in my example was really a fixed G/t. For a given fiscal stance, imports reduce national income (compared to the case when there are no imports). Because foreigners hold domestic assets and dividends and coupons are to be paid for it, it puts more downward pressure on national income.

However, one should really be looking at different (G/t)s because that is where the argument is. That really is the case where ceteris is not paribus. Before I head into that, I would like to point out that its rarely the case that governments change the G/t ratio in the present world, that is its not always the case that a current account deficit country goes into an expansionary fiscal policy. In fact they go into a contractionary policy which is a reduction in G/t. Some changes in the definitions of G/t can be made – using real instead of nominal or, adjusting for growth or simply comparing it with the national income. So when ceteris is paribus, continuous current account deficit is problematic.

So the question is whether the governments can act to prevent the leakage of income, even though governments do not pursue this aggressively in the present times.

To be continued . . .

“First, it must be remembered that for an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Net imports means that a nation gets to enjoy a higher living standard by consuming more goods and services than it produces for foreign consumption.”

IMO, if the imports are paid for with currency, it is a benefit. If they are paid for using debt, it is not.

anon-

“My impression is that mainstream economics uses these words in a generic sense wherever possible. There must be something deeply flawed with a system of thought that employs such vagueness so lavishly.”

Nobel Laureate Frederick Soddy-

” I thought that, as a scientific man, I ought to know something about economics. So I studied the money system for two years and could make nothing of it. Then, one day, the truth dawned on me. What I was studying was not a system, but a confidence trick.”

That’s why we’re here.

Dear anon (at 2010/06/22 at 22:25) and all

You wrote:

In fact, I just brought together a few blogs from last year into this one. It reveals that when readers make statements that MMT hasn’t considered this, or has ignored that, that the real problem is that the reader hasn’t read the body of work that is already available – both my academic work over many years and the more recent distillation of that work available via my blog.

This is not an attack on anyone but an invitation to go back through the archives of my blog – there are 2 million odd words already written – a lot of repetition – but most, if not all, of the issues that get raised have been considered and written about. Maybe not to the satisfaction of the reader but that is a different point to the accusation that we have deliberately ignored important points.

best wishes

bill

Dear Stephan

You asked:

If the “you” is me, then I do not. I haven’t the time to do that. I barely have time to keep this blog going. But I like to see the MMT army which is growing in size and full of zeal out there penetrating the denizens of ignorance.

With that said, it is hard to get through to the rabid gold bugs and you have to ask yourself whether foregoing a nice cup of tea with your partner/friend or whatever (doing a crossword) is worth the sacrifice. Especially, when their blogs carry advertisements for which they make money and the more hits they get the more money they make.

best wishes

bill

Dear Aidan (2010/06/22 at 22:54)

Your scratching for nothing. Even very sophisticated econometric analysis (studying lag structures etc) fails to reveal any statistically significant and robust relationship.

best wishes

bill

Dear Ramanan (at 2010/06/22 at 23:38) and anon

Endogenous just means determined “within the system”. Exogenous means the value is not the result of the system solution and is thus external to that solution. So the central bank can set the short-run interest rate – it has the legislative power and operational tools to impose that on the system. It is exogenous.

Deploring a word is not something that is worth spending time on.

best wishes

bill

Dear NKlein1553 (at 2010/06/22 at 23:49)

It is a matter of accounting. The foreign exchange transactions that are implied by the current account deficit have to be evidenced in the capital account. The balancing act comes via the reserve account which records the central bank transactions in the foreign exchange markets.

best wishes

bill

Dear Aidan (at 2010/06/23 at 0:13) and Richard (at 2010/06/22 at 23:44)

Australia had a massive depreciation in the early 2000s (down to 49 cents in the USD) but inflation was falling throughout this period. Inflation rose slightly as the dollar went towards parity in 2007.

best wishes

bill

“Deploring a word is not something that is worth spending time on.”

Exactly.

Dear Gary (at 2010/06/23 at 2:53)

You asked:

This is one of the quandaries of economic life. Do you try to maintain a small number (proportion of total) jobs by forcing all your population to pay more for goods and services which may also be of inferior quality – and in doing so, deprive poorer nations of the same means to develop that your own rich country used in an earlier historical period?

In posing the issue this way, I am not lacking empathy for the communities and families in the industrial areas that lose the employment. Far from it. But ultimately, if you allow trade and allow consumers to choose what is best for them, then these global resource allocations will occur.

But I do not support “free trade” – only “fair trade”. So I would ban products from nations where trade unionists are shot, or where wages and conditions are unfair. But even under fair trade these job reallocations will occur. So that is where I see a major role for government to stimulate new job opportunities via investment in education and R&D. Why hasn’t the US government , for example, seen the declining northern towns that used to make cars as the site for massive investment in renewable energy development and production?

best wishes

bill

“It reveals that when readers make statements that MMT hasn’t considered this, or has ignored that, that the real problem is that the reader hasn’t read the body of work that is already available”

Fine. Forget my suggestion. You must have already “considered” it. So you don’t need to “cover” it once more.

Clearly we are currently in uncharted territory- globally.

The good news is that we are are going to have some great data in coming years to re test the CAD debate, which was last at its peak in Australia in the recession of the early 1990’s. The RBA/Treasury line was then that domestic demand had to be crushed with extreme monertary policy settings to address a relativly moderate CAD. Remember the banana republic with a CAD at 5-6% of GDP.

Of course, now the conventional wisdom has turned fully circle, ie, the private sector can determine its own optimal level of contribution to the CAD, and any government borrowing should be spent on initiatives that improved nationally productivity like infrastructure.

Dear Ramanan (at 2010/06/23 at 4:35)

You said:

But you ignore the real benefits that arise from the imports. They help keep the “consumer” in good condition. I don’t think your analogy in this case is applicable.

Further, the loss of income to imports (actually net exports) provides fiscal room to create public goods and services without hitting the real capacity limits.

best wishes

bill

Wow, a lot of comments here:

First, you seem to be suggesting that there are only two policy options: flexible or fixed exchanged rates. But when some nations are pegging, the country pegged to can certainly impose tarrifs and fees to counterbalance some of the current account manipulation without resorting to a fixed exchange rate.

Second, in the statement

Because a nation imports more does not mean it consumes more — it can consume more, less, or the same amount. The geographic transfer of production from one nation to another does not mean that the nation losing capital enjoys a benefit of additional consumption. Whether or not it does depends on what else happens to the freed resources and what the multiplier effects are from the loss of income — you cannot use a partial equilibrium analysis here, and you need to distinguish between outsourcing — shifting production out of the country — with import competition.

But all the analysis assumes that the form of trade is import competition. According to this model there are Chinese firms that outcompete U.S. firms — this is not happening. This did happen with the trade deficit with Japan, but not with China. With China, we do not consume more — we consume the similar goods for a similar price, but the goods were made elsewhere, and the income for producing those goods also goes elsewhere. This obviously creates internal income imbalances with the U.S. and also with China, and requires a certain level of debt growth.

Third:

No — using the same cet. par. assumption that you assumed when arguing that net imports increase aggregate consumption, you would assume that a nation acquiring foreign capital would need to run a trade deficit due to the foreign capital inflows.

It’s bizarre to argue that developing nations need to, or historically have, experienced a net outflow of capital. As Krugman says, that is making “water run uphill”.

I don’t believe in either of these ceteris paribus assumptions.

Development requires trade, but not trade deficits. The whole purpose of flexible exchange rates is for the terms of trade to adjust leaving no long run surpluses or deficits.

Apart from the asian development model — which is recent — nations developed by running small deficits or relatively balanced trade up until they had all the foreign capital needed — which is small — and then they could use those skills and tools to provide more goods for their own domestic population as well as compete with foreign producers.

Even in the era of mercantilism, the trade surpluses were never viewed as a means for undeveloped nations to develop, but was a means for already developed nations to prevent others from developing due to the zero-sum mentality. Mercantilism was all about the nation with the most advanced business sector and strongest navy forcing open the markets of weaker, less developed nations.

>However, the fact it faces no financial constraints is not a sufficient condition for a sovereign government being able to advance public purpose. The latter goal relates to maximising domestic outcomes including environmentally-sustainable growth, low unemployment, real wages growth in line with productivity, and inclusive social policies.

Its called “GPEC”

http://delusionaleconomics.blogspot.com/2010/06/gpec-how-could-australia-get-more-of-it.html

The point is to find a balance between all of these.

“The balancing act comes via the reserve account which records the central bank transactions in the foreign exchange markets.”

Can someone explain to me what exactly happens in this balancing act? Assuming there are only two countries, the U.S. and China, here are some hypothetical transactions that might take place along with my questions:

1) The U.S. runs a current account deficit transferring dollars from the U.S. commercial banks U.S. importers use into the Chinese commercial banks Chinese exporters use.

2) The Chinese commercial banks exchange the dollars Chinese exporters earned into Chinese Yuan and credit the Chinese exporters’ bank accounts with Yuan. My question is who facilitates this exchange? Is the Chinese central bank exchanging the dollars Chinese exporters earned for Yuan? Or are there private financial institutions that do this? Or both?

3) Chinese financial institutions (including possibly the Chinese central bank) now hold the dollars the Chinese exporters earned through trade. My question is where are these dollars held? Are they held in a special reserve account set up by the Chinese central bank? Or are they held in a reserve account set up by the U.S. central bank (the Federal Reserve)?

4) Presumably Chinese financial institutions (including possibly the Chinese central bank) will want to do something with these dollars besides hold them as reserves in some account somewhere. Perhaps Chinese financial institutions will convert their dollar reserves into a dollar denominated financial asset like a treasury bond, corporate bond, or some equity instrument. Or maybe the Chinese financial institutions will choose to invest in a tangible asset like real estate or industrial machinery instead. My question is do Chinese financial institutions have to actually invest their dollar reserves in something (bonds, shares, industrial equipment, real estate, etc…) for the U.S. to run a capital account surplus? Or does the mere fact that Chinese financial institutions possess dollar reserves equate to a U.S. capital account surplus? Again, maybe it is just my unfamiliarity with accounting terminology, but I would think that for the U.S. to run a capital account surplus the Chinese financial institutions would have to use their dollar reserves to actually invest in something. But then I don’t see why the mere fact that the U.S. imports more than it exports (a current account deficit) should *force* Chinese financial institutions to make some sort of an investment. They could just sit on their dollar reserves if they were so inclined. It might not make much economic sense for them to do so, but they could. So what is the mechanism that translates a U.S. current account deficit into a capital account surplus?

Sorry for all the questions. I know this blog isn’t supposed to be an economics tutorial just for my benefit so Professor Mitchell if you want to delete this post I would understand. Although, maybe other neophytes have questions similar to mine. I should probably know this stuff anyway as I sometimes teach economics to high school students. It’s just that I’ve never been too clear on precisely why the current account equals the capital account even though I’ve read and reread the relevant sections of my college econ textbooks several times. Thanks in advance to anyone who can help me.

And in regards to the asian development model, I’d recommend the comments of Michael Pettis — from his most recent post

NKlein1553,

“So what is the mechanism that translates a U.S. current account deficit into a capital account surplus?”

Thought I answered that in first principle terms. It’s a debit drawn on a US bank account (e.g. check, draft, wire transfer, etc.), paid to somebody in China, who must get credit for the same amount, which ultimately becomes a claim on a US bank. The debit is the current account outflow. The credit is the capital account inflow.

Most of that capital account flow gets transferred to the Chinese central bank when exporters sell their dollars to their commercial banks who then sell them to the PBOC. Central bank reserves are a capital account outflow.

You’ve asked some really great questions about the underlying operational details.

Unfortunately, you won’t get the detailed answers here.

Except that most of the dollars flow into the Chinese central bank and are held there as reserves. The bank buys treasuries with its dollars. That’s a mere asset composition change within the capital outflow classification.

The central bank is “the box” on FX transactions and capital account outflows, because substantial Chinese capital (flow) controls are in place in both directions.

In regards to the interest rates, I would very much wish to push this debate further by asking the participants to fully specify the banking system regulations in place.

Clearly the arrangement we have now have led to financialization and economic rents. And yes, under this arrangement, banks can purchase government assets with zero risk-weight to their capital requirements, meaning that banks can use reserves to buy short term government assets risk-free. In that case, they are happy for the interest payment — for any interest payment, really.

But the MMT proposal is to prevent banks from purchasing any asset other than loans that they make to customers. That means that banks cannot buy bonds. And in that environment, you will not be able to use this mechanism to allow the interbank rate to propagate to short term rates.

So the level of “control” the government has depends heavily on the set of institutional arrangements that are in place.

When talking about these rate trade offs, please specify the set of assumptions that you are making on the banking sector. Are you working in

* current reality, in which the government is revenue constrained, the central bank is independent, and banks carry risk and balance sheet penalties for purchasing assets that limits their ability to arbitrage between their marginal cost of reserves and the market price of assets that they can hold.

* Mosler’s/Bill’s MMT reality, in which banks cannot buy government bonds or any other traded instruments, and must only hold cash and loans they directly made to their customers.

* Chinese model, in which banks can buy anything and are not responsible for losses, but in exchange must charge government mandated interest rates.

Only in the third version of reality does the government directly control interest rates. In the second version, the government controls the (long term) cost of housing and real estate only. In the first version, the government can influence, but not control, a bit of both.

At the end of the day, interbank rates are a hidden variable of the banking system. If, tomorrow, we nationalized the banks, the economy would still continue to function and we would still have the full yield curve. There is nothing that requires OMO in order to set interbank rates. And yet you argue that the interbank rates control all the other rates. It stands to reason that there would be a propagation mechanism of allowed bank actions — in terms of the assets that they are allowed to purchase and the liabilities that they are allowed to issue — that can make this happen.

Therefore any statement about rates need to be supplied with a fully specified context so that the propagation mechanism can be judged.

Moreover, until you fully specify the banking system, it will be impossible to determine the effects of the no bond proposal as well.

So the next question is…

If the chinese do manage to change migrate their economy to a more sustainable model based on local demand not on exports, meaning they care less about the yuan currency peg, what are they going to do with the massive US reserves.??

What would the chinese need that the US can provide them for their US coconut shells ?

Hoju,

That is a good question, and highlights the difference between the simple view that we have been getting excess goods from China and the more complex view that we have been expanding our supply chain and shifting production to China.

If the first view was correct, then they would just start buying up U.S. output, increasing their standard of living — except that the U.S. output is made in China!

Oops.

Suppose an iPhone costs $670, $5 of which is paid to chinese laborers that assemble it, $10 is paid to coordinators to oversee that process, $200 is paid to other east asian component manufacturers who themselves outsource production to China along similar ratios (P. will like the “fractal” nature of this manufacturing process), $10 of non-hardware costs is paid to American programmers and designers, $70 is paid in royalties to patent holders, and throw in $10 for shipping, packaging, and cables. That leaves a gross margin of about 60%, or $370. Let’s keep it simple and assume that gross value added is $370.

According to NIPA, that $370 contributes to America’s final output. Apple has “created” $370 dollars worth of goods, which, when properly deflated, constitute final output, even though the actual iphones were built overseas.

The fact that the terms of trade are such that the Chinese workers get $5 instead of $50 dollars means that U.S. output is higher by $45.

Then Bill says that we are enjoying the consumption of $45 more worth of stuff. No, we are not. If those savings are passed on in the form of higher wages or higher spending by those with capital income, then we would be. But nothing guarantees this, and in reality, the high gross margins do not translate to higher levels of domestic consumption.

When you are talking about profit-boosting outsourcing, then it is “investment” — as measured by NIPA using the S=I identity — that is boosted, and not consumption.

But the measurement of that investment is subject to many tortuous and dubious economic deflations in order to finagle Investment (which is a “real” quantity) to be equal to Savings (which is a financial quantity). A priori — the units don’t even agree.

In the specific case of the iPhone, I claim that if the Chinese were paid $50, then Apple’s margins would fall, but iPhone prices would not increase, and U.S. households would continue to buy the same number of iPhones as they did before, but holders of capital would be somewhat poorer, and asset prices would be somewhat lower. Total output would decline somewhat — as measured by NIPA — but in reality both real investment and real consumption would not decline.

However the trade-deficit would increase, which Bill argues means that we are consuming even more. Good for the representative household!

“There are other ways to show this as well but sufficient to say at this point that unless the government compensates this, national income is inversely proportional to the propensity to import. It is true that budget deficits are endogenous, but for a fiscal stance, there is nothing automatic to bring the employment back to the original level. Ceteris paribus imports increase unemployment”

Personally, I think this is a very important point. If governments, operating out out a neo-liberal paradigm, refuse to provide the offsetting fiscal stimulus (either via tax cuts or more spending) to ensure that the economy remains close to full employment, then the “exports are a cost, imports are a benefit” argument does lose some of its force, because it implies an ongoing output gap unresolved through, say, Bill’s Job Guarantee idea. Absent a proper fiscal stimulus, many of the benefits of imports are potential and not fully actualised.

And while we are on the subject of looking (ever so superficially) at actual behavior of firms and households under different interest rate and current account regimes, let’s not ignore Dani’s recent contribution discussing an IADB report contrasting the periods of Import Substitution policies and Washington Consensus policies in Latin America (IS vs WC)

Which goes to show that an inefficient industrial sector is better than having no industrial sector at all.

None of these structural shifts require the rogue’s gallery of a bank-dominated financial sector, low interest rates, massive trade imbalances or export-led growth.

NO! I would not talk about interest rates again…..I think? I have covered it so amy times in many comments and I am tired of it. Actually, Bill in this post, as I understand him, is now very close to my position. Anybody with knowledge of Control theory will understand that you control when you match an instrument with a target because you set the instrument and manage the mechanism that determines the target. On the other hand, you can only partially support a target within a range band when the degrees of freedom within the mechanism reduce your capacity for control. So, CB everywhere, please forget LT rates and focus on the very ST rate set.

Regarding managing excess reserves, RSJ is right about the need to consider capital adequacy considerations for bank asset allocation. As Ramanan sais banks can opt to repay CB loans with their excess reserves. Furthermore, the can also purchase foreign reserves and interest earning risk free foreign state bonds and this can reduce the need to issue/sell domestic state bonds and absorb excess reserves. Also if the risk differential is reduced, there are many studies that show that banks increase their risk taking attitude and they expand credit lines, engage in off balance sheet activities and reduce credit rationing as the asymmetry of information cost is reduced.

Yes anon you did answer my question, but I thought a more detailed operational explanation would help my understanding. I don’t know why, but the fact that “central bank reserves (dollars held by the PBOC) are a capital account outflow (to the U.S.),” seems counter-intuitive to me. Thanks to you I understand the classification scheme (I think), I’m just not sure why the terms in the classification scheme are what they are. In fact, I still don’t really understand why the dollar reserves held by the PBOC are classified as capital account outflows from China to the United States if the dollars are just sitting in a reserve account somewhere. If these dollar reserves held by the PBOC are used to make an investment, that is once these claims on a U.S. banks are called in, then I wouldn’t have any trouble seeing them as adding to the U.S. capital account surplus. I’m sure there is a rhyme and a reason to the classification scheme though and I’m just being dense. Thanks again for the explanation and your patience.

Exactly, P, I am trying to force people to commit to describing their proposed changes so that they can describe how these rates propagate.

It all depends on what we let banks do with the government-set funding costs that we give them. That will determine how the government-set bank cost of funds influences the credit market rates.

Then we can have a discussion about the effects, both intended and un-intended, of the proposed suite of changes.