I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

OECD – GIGO Part 2

The OECD is held out by policy makers and commentators as an “independent” authority on economic modelling. The journalists love to report the latest OECD paper or report as if it means something. Most of these commentators only mimic the accompanying OECD press release and bring no independent scrutiny of their own to their writing. Government officials and politicians also quote OECD findings as if they are an authority. The reality is that the OECD is an ideological unit in the neo-liberal war on public policy and full employment. They employ all sorts of so-called sophisticated models that only the cogniscenti can understand to justify outrageous claims about how policy should be conducted. In an earlier blog – The OECD is at it again! – I explained how the OECD had bullied governments around the world into abandoning full employment. Now they are providing the “authority” to justify the claims being made by the austerity proponents that cutting public deficits at a time when private spending is still very weak will be beneficial. The report I discuss in this blog is just another addition to the litany of lying, deceptive reports that the OECD publish. These reports have no authority – they are just GIGO – garbage in, garbage out!

In his excellent 1973 book – Economics and the Public Purpose – John Kenneth Galbraith wrote (page 7):

Part of the (ideological) service (of economics) consists in instructing several hundred thousand students each year. Although gravely inefficient this instruction implants an imprecise but still serviceable set of ideas in the minds of many and perhaps most of those who are exposed to it. They are led to accept what they might otherwise criticize; critical inclinations which might be brought to bear on economic life are diverted to other and more benign fields. And there is great immediate effect on those who presume to guide and speak on economic matters. Although the accepted image of economic society is not the reality, it is what is available. As such it serves as a surrogate for the reality for legislators, civil servants, journalists, television commentators, professional prophets – all, indeed, who must speak, write, or act on economic questions.

It is a quote I think about a lot because it reflects on how economic theory is held out as an authority – full of laws and natural constructs as if it is on the same level as the physical laws of science – but which in reality is an ideological collection of unprovable assertions that generally fail to have any informational content when confronted with the empirical world.

The OECD recently published a paper – Prospects for growth and imbalances beyond the short term – which purported to demonstrate that maintaining the current fiscal positions was a dangerous strategy whereas fiscal consolidation (the euphemism for austerity) combined with structural reform (the euphemism for cutting workers wages and entitlements and privatisation more public wealth at discount prices) was the best long-term outcome facing governments.

These sorts of documents are used by the policy makers and commentators to reinforce their positions as if they mean anything. The reality is that for those who understand the way the OECD constructs its underlying simulations (like me) the papers are meaningless.

They are just technical exercises, which disempowers those not technically trained in the tools and techniques that are brought to bear. But like all models their capacity to say anything about the real world we live in depends on how the underlying economic models are structured and the assumptions used in the policy scenarios.

When you dig into these models you soon learn to identify those that are just pure ideological statements. The models then attempt to provide an authority for what is otherwise a rehearsal of the intense ideological dislike that mainstream macroeconomists have for use of fiscal policy and its willingness to allow unemployment to persist at high levels for long periods of time.

All this is dressed up in terms of fiscal responsibility and concepts like the NAIRU.

Please read my blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

The OECD were not always like this. One of my Phd students who has nearly completed a masterful piece of research on the political constraints to full employment and documented in some detail the way the OECD was turned into a useful economic research organisation of a Keynesian flavour into an ideological tool to serve the neo-liberals. The next few paragraphs draws on Victor Quirk’s work (he is a sometime guest blogger here and will return with much more in coming weeks after he submits his thesis).

Victor writes:

During 1969, the first year of Richard Nixon’s Presidency, regime change was affected at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This organisation formed in 1960 as a consultative forum and policy clearing house for the industrialised nations through which techniques of macroeconomic management and economic development could be evaluated and shared between the officials of member states …

In the 1960s, the OECD had a distinctive Keynesian flavour.

In Martin Marcussen’s 2001 paper – The OECD in Search of a Role: Playing the Idea Game – we read (page 5) that:

…the key to effective fiscal policy therefore lies in appropriate discretionary action: the budget should be made more expansionary if the expected level of demand falls short of that required to meet the various objectives of economic policy. Conversely, it should be made more restrictive if, in the light of these aims, the expected pressure of demand is judged to be too high.

After an enquiry into how demand management policies could be compatible with inflation control, the OECD published its response in 1970 – Inflation: the Present Problem – under the new directorshop of Dutchman Émile van Lennep, a neo-liberal.

Victor writes:

The report argued for higher priority to be given to price stability which would entail “giving a lower priority to something else”, i.e., increasing unemployment.

From that point (which was well before the first OPEC oil shock, which is typically the event that commentators mark as the beginning of the neo-liberal period) the OECD has been pushing the anti-fiscal policy line.

Its model development is entirely biased to creating structures that deliver estimates and simulations which undermine the confidence we might have in the effectiveness of fiscal policy. They are not to be believed.

As background to this blog I would recommend you read the blog I wrote earlier – GIGO – which is shorthand for garbage in, garbage out. Today’s blog is GIGO Part 2.

OECD simulations

The OECD paper opens by saying that:

Repairing the damage wrought by the downturn and getting economies back onto the path of strong, sustainable and balanced growth will require concerted efforts in a number of policy domains, including fiscal consolidation targeted at reducing government debt over the medium-to-longer term, some realignment of exchange rates and structural reforms that will boost growth and welfare while at the same time rebalancing the sources of world demand.

On the basis of policy simulations, this note reports different scenarios for the world economy to identify what combination of policies is likely to be most success.

The policy simulations are (see the paper for full detail):

- The business-as-usual scenario for each country – where the “primary budget deficit is reduced by 0.5% of GDP per year for as long as needed to stabilise the ratio of government debt to GDP.” Long-term interest rates rise “for every additional percentage point increase in the government debt-to-GDP ratio above 75% of GDP”. Output gaps are closed by 2015. Interest rates are normalised by 2015. Inflation is targetted at 2 per cent. So I would call this a moderate austerity package given the state of private spending at present.

- The fiscal consolidation scenario – where “(a)ccelerated fiscal consolidation starts in 2011 and reduces government debt-to-GDP ratios by 2025 to the pre-crisis levels” with some variations for Japan. The OECD says that “fiscal consolidation is seen as credible and the fall in bond yields associated with lower debt (than the business-as-usual scenario) is therefore front-loaded” (more later but be suspicious). OECD exchange rates fall by 10 per cent immediately and then another 10 per cent over the next 10 years after markets applaud the announcement of consolidation (again be suspicious).

- The structural reform scenario – “private and public savings are lowered by 3% of GDP in China and other non-OECD Asian economies, private demand is raised by 2% of GDP in Japan and private savings are raised by 1% of GDP in the United States – phased in over years. Structural reforms reduce unemployment by 2 per cent over next 8 years in Euro area (be suspicious). Renminbi appreciates by 20 per cent and US dollar depreciates by 10 per cent which, conveniently “allow for the impact on GDP of lower (higher) private savings in China (United States) to be compensated by lower (higher) net exports” (again be suspicious).

So the order of “reforms” are to introduce the fiscal consolidation scenario which reduces “the ratio of government indebtedness to GDP by 2025 to pre-crisis levels” but has only “a limited impact on external imbalances, in part because all OECD economies would engage in consolidation simultaneously” then to augment the consolidation with “with structural reforms to reduce (raise) savings in surplus (deficit) countries, especially China, dynamic non-OECD countries in Asia and the United States, and reduce unemployment in the euro area”.

How do they come up with these simulated results? For every simulation there has to be an economic model of some kind whether it be a calibrated numerical model or an estimated econometric model or some hybrid.

As it turns out the model used is the OECD Global Model and you can read an introductory paper about the model HERE. It is a little technical so you may want to save your bandwidth and leave it.

This model is one of those curious models derived from the New Keynesian literature. This school in economics claim they are not neo-classical (that is, neo-liberal) but the reality is that the only variation from the extreme neo-classical models is in their assumption that there is some nominal wage and price inertia which prevent the economy from price-adjusting in the very short-run.

All the long-run results from the simulations are neo-classical which means that aggregate demand (and hence fiscal policy) has no long-run effect on real outcomes (GDP growth, employment, income generation etc). I will come back to that.

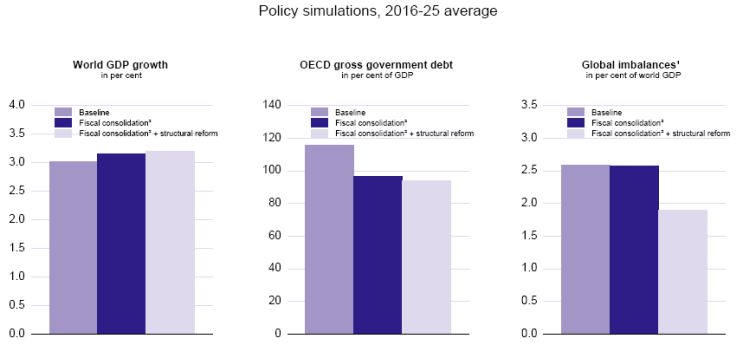

The following graph is a reproduction of the OECD’s Figure 1 which summarises the results of the simulation for the three scenarios across the major aggregates of interest – World real GDP growth; OECD gross government debt (per cent of GDP) and Global imbalances which is a “summary measure of global current account imbalances” and “is constructed as the absolute sum of current balances in each of the main trading countries or regions”.

You can see why they conclude that as you introduce fiscal consolidation and then augment it with the structural reform measures the outcomes across the three aggregate measures “improve”.

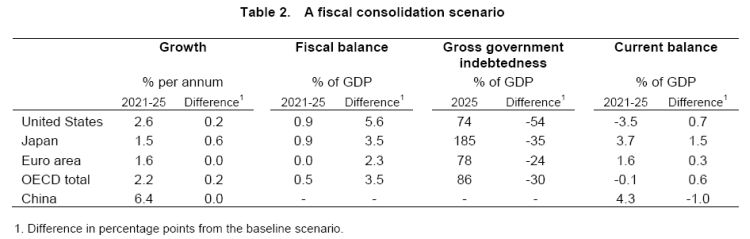

The next Table is reproduced from Table 2 of the OECD paper and shows the results of the fiscal consolidation simulation. The column marked “differences” shows “the difference in percentage points from the baseline scenario” which is the business-as-usual scenario.

So in terms of the fiscal balance for the whole OECD area the baseline estimates over the period to 2021-2025 that nations will run an average deficit of 3 per cent of GDP whereas the fiscal consolidation strategy yields a budget surplus of 0.5 per cent of GDP over this period.

The results all suit the austerity proponents. They get even “better” from their perspective when you add in the structural reforms.

Private saving implications

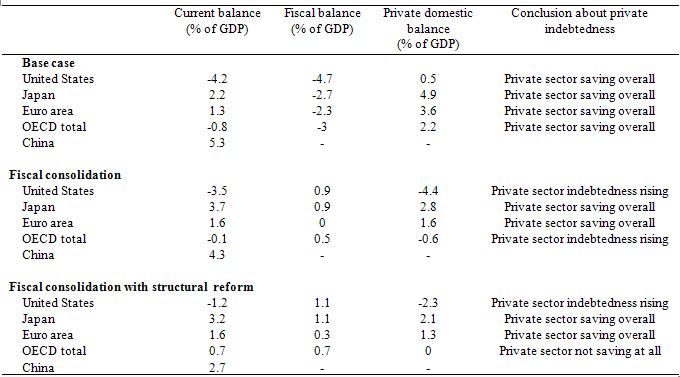

I put together the simulated outcomes for the public and external balances for the three scenarios and estimated the implied private domestic saving balances that would be averaged over 2021-2025. I used the sectoral balances framework which should be familiar to you by now. Please read the blog Stock-flow consistent macro models for the derivation.

Basically from the national accounts the following relationship has to hold:

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

The following table compares the three OECD simulation scenarios. Only the baseline scenario (which I would still call austerity under the current circumstances) allows for consistent private sector debt retrenchment over the long-term. In the fiscal consolidation scenario, the private sector for the overall OECD area is dis-saving and thus would have been accumulating debt over that period.

The models do not allow for Minksy-dynamics (discussed in yesterday’s blog – Counter-cyclical capital buffers) and so do not allow for the stock-flow implications of a government running a surplus and the private sector continually increasing its debt exposure.

The scenarios that have the US private sector and the OECD in total continually in deficit are not sustainable over the period modelled. Even under the radical option (fiscal consolidation and structural reform) the OECD total private sector breaks even – that is, there is no saving. That is not going to happen and thus brings into question the validity of the underlying model structure.

None of this is addressed in the OECD paper (or supplementary material) – they just ignore these implications.

What drives this model?

I don’t intend to go into a lengthy explanation of the structure of the model used by the OECD because time doesn’t permit and it would get very technical anyway. But I can give you a flavour of how the model works.

In the model description we read:

Overall, the broad structure of the new model is similar to its predecessors in certain respects, with country and regional models combining short-term Keynesian-type dynamics with a consistent neoclassical supply-side in the long run. The presence of nominal rigidities in wage and price setting serve to slow the process of adjustment to external events, so that output is largely demand-driven in the short term, but supply-driven in the longer term.

So essentially this is a neo-classical model that says that employment is a function of the real wage and not demand and inertia allows the government to increase output and employment in the short-run by exploiting the rigidities in prices and wages.

The model imposes a NAIRU (natural rate of unemployment) on the economy which is invariant to aggregate demand. It is somehow an aggregate driven by “structural rigidities” etc but when you get down to the supporting papers that the OECD has published in the past (for example, Estimating the structural rate of unemployment for the oecd countries you learn how crooked this concept is.

Thus, while real wages do not adjust in the short-run to “clear” labour markets, eventually, the aggregate demand stimulus generates wage and price inflation as “the gaps between expenditures demand and potential output (GAP) and the actual and underlying structural rates of unemployment (UNR and the NAIRU)” close. The result is that the economy returns to these arbitrarily imposed steady-states.

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – we showed that a lot of the so-called “long-run structural variables” were all driven by the business cycle – that is, aggregate demand. So they were not independent of fiscal policy.

Please read my blogs – Redefining full employment – again! and The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

In my PhD thesis (and an early article published in Australian Economic Papers in December 1987 which was based on my PhD research) I wrote:

Recent policy orientation in the U.K., the U.S.A. and in Australia is based, it seems, on the view that inflation is the basic constraint on expansion (and fuller employment). A popular belief is that fiscal and monetary policy can no longer attain unemployment rates common in the sixties without ever-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment (NRU) which is the rate of unemployment consistent with stable inflation is considered to have risen over time – labour force compositional changes, government welfare payments, trade-union wage goals among other “structural” influences are implicated in the rising estimates of the inflationary constraint.

In that research, I showed that the increasing NAIRU estimates (based on econometric models) merely reflected the decade or more of high actual unemployment rates and restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and hence, were not indicative of increasing structural impediments in the labour market? I also showed that there was no credibility in the claims that major increases in unemployment are due to the structural changes like demographic changes or welfare payment distortions.

For the technically minded you might like to read the original article which appeared in Australian Economic Papers, December 1987 which has the formal theoretical model and econometric analysis.

This work was part of a new research agenda that was able to show that structural changes were in fact cyclical in nature – this was called the hysteresis effect. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

I produced a theoretical model which showed that any structural constraints that emerge during a large recession (more about which later) can be wound back by strong fiscal policy stimulation. I have also produced several empirical articles during that period to verify the claims.

What are the facts?

Recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again. But this behaviour has to be seen in the context of the policy position that the national government takes at the time of the recession and the early recovery period. As I show below, this has made a significant difference in Australia.

It is true that once unemployment reaches high levels it takes a long time to eat into it again because labour force growth is on-going and labour productivity picks up in the recovery phase. You need to run GDP growth very strongly at first to absorb the pool of idle labour created during the recession unless you provide a strong public employment capacity that is accessible to the most disadvantaged (for example, this is what the Job Guarantee is about!).

It is also the case that if GDP growth remains deficient then the idle labour queue will remain long and employers will use all sorts of screening devices to shuffle the workers in the queue. They increase hiring standards and engage in petty prejudice. A common screen is called statistical discrimination whereby the firms will conclude, for example, that because on average a particular demographic cohort is unreliable, every person from that group must therefore be unreliable. So gender, age, race and other forms of discrimination are used to shuffle the disadvantaged from the top of the queue.

The long-term unemployed are also considered to be skill-deficient and firms are reluctant to offer training because they have so many workers to choose from.

But to understand what happens during a recession we need to consider the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

An extensive literature links the concept of structural imbalance to wage and price inflation. It can be shown that a non-inflationary unemployment rate can be defined which is sensitive to the cycle. Given that inflation typically results from incompatible distributional claims on available income by firms and workers, unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital. This is the underlying reason why inflation targetting uses unemployment and a policy tool rather than as a policy target!

Why is all that important? Answer: because the long-run is never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

In the blog – The Great Moderation myth I presented the following diagrams which also bear on the point.

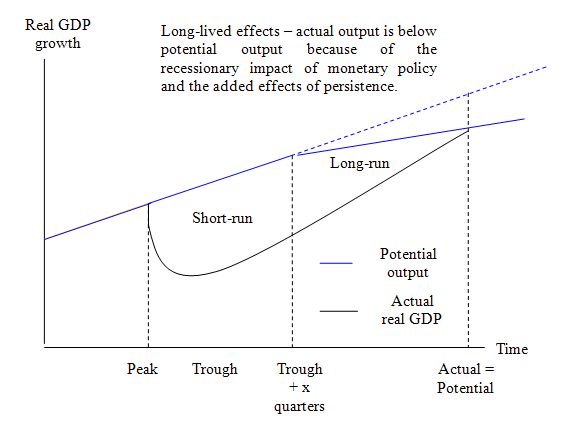

Hysteresis theories purport permanent losses of trend output as a consequence of the disinflation. The following diagram shows that the real GDP losses are much greater than you would estimate if you used the neo-classical long-run constraints imposed by the OECD.

You can see that potential output falls after some time (as investment tails off) and actual output deviates from its potential path for much longer. So the estimated costs of the disinflation (and fiscal austerity supporting it) are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit.

But the point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken. Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that.

By imposing these artificial conservative constraints on their simulations, the OECD is guaranteeing that the main neo-liberal results hold in the long-run. There is no informational content at all in their outcomes.

You can also see other ideological constraints imposed on the model when you examine its policy structure.

The OECD outline their monetary policy assumptions like this:

Consistent with developments in other international macroeconomic models, monetary and fiscal policy settings are endogenous in the model, although alternative policy rules can be set to override the specific defaults. Monetary policy is assumed to be typically set using a Taylor-type rule so as to return consumer price inflation to its baseline level in the medium term. Thus, short-term policy-determined nominal interest rates respond to any increase in inflation and also to movements in the output gap.

So interest rates rise to combat inflation which is a product of fiscal policy expansion. In turn, there are a very high in-built sensitivity of output to interest rate changes (which doesn’t exist in the real world). The only sustainable position is the NAIRU-supply-side constrained position. So by assumption things settle at that point and less fiscal policy will always deliver “better” outcomes (by construction).

On fiscal policy, the model assumes:

In simulation, the long-term stability of the fiscal balance, and hence the debt stock, is ensured in the model by adopting an endogenous fiscal rule. Thus, if there is any permanent rise or fall in final expenditures, tax revenues will need to rise or fall to offset changes in the fiscal balance and debt stock. In practice, such rules are imposed fairly gradually over time implying, for example that the effects of any short-term fiscal action on the government deficit is eventually reversed and offset over a longer term period to ensure longer term solvency.

So the long-term position imposed on the model is that increasing deficits are “paid for” by tax rate increases to ensure that some artificial public debt ratio is stabilised.

There is very little empirical basis for this assumption. In general, history shows us that GDP growth erodes the public debt ratio as the automatic stabilisers kick in and reduce the public deficits. That process sees tax revenue rise but doesn’t rely on tax rates rising.

What you get are linkages like this. Increases in government net spending increase interest rates which “crowd out” private spending and net exports (via a reduction in competitiveness due to inflation). The assumed loss in aggregate demand from the crowding out is complete in the long-run.

Thus:

At the same time, monetary policy tightens and short-term interest rates increase, whilst progressive increases in tax rates required to restore fiscal balance gradually reduces the overall fiscal stimulus. Although output is essentially pinned down in the very long run by relatively fixed supply potential in the model, its path is affected by underlying adjustment dynamics and for some countries/regions a degree of damped cycling cannot be ruled out, with short-term positive gains being offset in the medium term as the boost to output is put into reverse.

So you get what you assume and there is no meaningful information in the results if the underlying theoretical constructs have no relevance.

The OECD tries to concede to empirical realities by allowing for short-run divergences from the results presented to students in the mainstream textbook model. But that concession doesn’t last and so their underlying conclusions (and the adjustment path the economy takes) is “pinned down” by the neo-classical assumptions.

There is no empirical basis for employing those assumptions and thereby using them to influence the entire short-run dynamics of the model.

In closing, I could have gone into all this in great detail.

But you get a hint of how loaded the simulations are when you read that “fiscal consolidation is seen as credible and the fall in bond yields associated with lower debt (than the business-as-usual scenario) is therefore front-loaded”.

So are bond yields rising in the US? Answer: No!

Have bond yields been rising in Japan? Answer: They have been running historically large deficits for years and now have a public debt ratio closing in on 200 per cent of GDP. Bond yields have been very low and stable for some decades in Japan.

So to front-load something that only has an existence as a theoretical predeliction of the neo-liberals which reinforce the likelihood of gaining a favourable mainstream outcome in the simulations is very telling. There is nothing in the empirical space which would justify loading the simulations in this way.

Conclusion

GIGO.

You can get any result you choose by structuring the model in whatever way you like. The imposition of a mythical “neo-classical long-run” that has no empirical or theoretical basis drives all the long-term results and anchors the model at a point that is consistent with the neo-liberal claims.

The results are not “independent” information. They are what you get when you assume the economy functions in a particular way.

That is enough for today!

Postscript

All credit to Wikileaks for allowing democracy to work just a little better. This exposes the worst side of government, which incidently all the neo-liberals love – they always love public deficits when they be driven by tax cuts or increased military spending. The word hypocrite comes to mind.

This is off topic, but it’s another instance of Euro “garbage in garbage out” report, which irritated me.

It was a long report produced by some Euro organisation which looked at the alleged additional earnings derived from getting a university degree. It made the amazing discovery that graduates earn more than non-graduates – a point which is no more than common sense. Problem was that the report failed to control for family background of students, and that is a fatal flaw. Reasons are thus.

People from stable (and especially middle class) backgrounds tend to go to university, plus they tend to earn more even if they DON’T go to university. Thus the fact that graduates earn more than others tells us nothing about the EXTENT to which this effect is attributable to getting a degree. E.g. three quarters of the “additional earnings” effect could be attributable family background!

As to studies which DO control for family background, the only one I’ve looked at indicated that arts degrees for men are a waste of time in that they produce no additional earnings. In contrast, all other degrees DO yield a financial return: that includes all degrees for women, and vocational and science degrees for men.

Actually economists are dead wrong with their conception how physicist work. Heinrich Hertz wrote about “our conception of things”. He spells out 3 criteria for choosing among different conceptions of the same phenomena. First it must be “permissible” meaning logically consistent. Second it should be “correct” in the empirical sense – all up to the present observable phenoma do really and correctly correspond to the conception. The third criterion is it must be “appropriate” to the scientific purpose undertaken.

Now “permissible” can be answered with yes or no and this answer holds good for all time. The answer if “correct” can also hold but only in regard to the present experience. But “appropriate” is open to ambiguity and differences of opinion may arise. Opposite to economists believe physics requires and needs pluralism in the conception of things due to this ambiguity. The monism (school which holds the whole truth) in economics stems from a not understanding how physics actually operates.

I.e. the switch from Newton to Einstein caused philosophers to reason that in science there’s a battle of ideas with a complete paradigm shift which draws one idea useless (untrue) once the other idea falsified it. But that’s not the normal way things work. You can a look at matter and light by means of waves and corpuscles. Both ways proved essential but they can not be reduced to terms one of the other.

I can remember in the late 1990s people (well, economists actually) were suprised at how US low inflation was as the unemployment rate kept going down. There were at least a few people saying that the NAIRU must be going down, rather than saying that perhaps their model was wrong.

Brad de Long posted a link to this paper on hysteresis that may be of interest to some MMT types and readers.

http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/conf/conf53/papers/Ball.pdf

My take is that some mainstream New Keynesian types are revisiting hysteresis- but they seem to have trouble translating the existence of hysteresis effects into an alternative monetary policy framework to inflation targeting.

worth a read anyway

Re: WikiLeaks – why are there so many bright and enlightened Australians in the world? What are we doing wrong in the UK?

Anyway, I am trying to figure out if I’m right about something:

Spending (Investment) CAN cause inflation in some circumstances, but saving can’t. I think this is because inflation is caused by ‘too much money chasing too few goods’, but savings are just sitting there – so they cannot be chasing ‘too few goods’ – is this correct?

Another question:

In a rational world with no irrational currency speculation – an increase in the money supply COULD cause the price of the currency to fall, but only that proportion of the increase that is being spent (not saved) could/should do this. Is this right? I imagine that when we freeze time, money being saved is not circulating, and therefore should be treated as only increasing the POTENTIAL to spend. In a rational world, when it is actually spent, then it might contribute to a fall in the price of currency. Is this along the right lines? Am I being stock-flow consistent? Am I using the right words? Am I completely wrong?

Kind Regards

Charlie

I wouldn’t waste my time reading anything written by a bloke like Larry Ball who is friends with a non-event such as Mankiw.

Biased ? Sure but lifes too short to read that garbage.

The only thing good to come out of Chicago in the last 30 years was The Blues Brothers.

Charles J: Re your first question (money “chasing too few goods” etc) your suspicion that money cannot be inflationary till it is spent is correct: David Hume made this point in his essay “Of Money” 250 years ago. As he put it in that essay “If the coin be locked up in chests, it is the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated…” See:

http://socserv.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/hume/money.txt

Re your second point, I think you are correct. In fact your second point follows logically from the first, seems to me.

I seriously doubt David Humes comments were for a modern money economy given that he wrote it 250 years ago.

Today we have so many more forms of money / near money which never existed back in Humes day. In addition, Hume was not even writing about a capitalist system.

Money For Nothing. Chicks for free. (Mark Knopfler, 1985)

probably just as irrelevsnt as quoting Hume.