I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Polly wants a cracker

If you watch the 1937 cartoon – I Wanna Be a Sailor – it doesn’t take much imagination to think of the first two young parrots on the perch who are being taught their “skills” by a somewhat vexed mother parrot to be mainstream economists and the financial commentators who parrot these economists. Repeat after me: Polly wants a cracker – the Budget deficit is on an unsustainable trajectory – Polly wants a cracker – there is a mountain of public debt that threatens America’s future – Polly wants a cracker. If only these economists would take the lead of the third little parrot being coached by his mother. When he is exhorted to recite the mindless mantra that is expected of him he says “I don’t want a cracker see, I wanna be a sailor like my pop … see” … we need more commentators who will ask the right questions – challenge the politicians and their lackeys to explain what they mean rather than talk as if it is too complex for us to comprehend. It is not complex at all – spending equals income – if the private sector goes on holiday the public sector better be around town. If the private sector stays on holidays – the public deficit will persist. Otherwise – recession occurs and unemployment increases. The problem is that the mainstream commentators and the economists that provide them with the copy haven’t got off the perch yet and recite the same mindless stuff day-in, day-out. Polly wants a cracker.

Nearly a year ago I wrote this blog – Chill out time: better get used to budget deficits – where I explained that a detailed examination of the sectoral balances in the OECD nations revealed a massive drop in private demand since 2007.

The mirror image of that spending collapse was the increase in public deficits via the automatic stabilisers and the discretionary stimulus packages that governments chose to implement. These swings signalled that economies were adjusting back to more normal relations that have been evident for many years – that the private sector typically saves overall and the government sector typically runs budget deficits. The neo-liberal period – dominated by an ideological distate for public deficits and government activity in general – perverted these historical normalities.

By pressuring governments to adopt restrictive fiscal settings (to act as passive support for an inflation-obsessed monetary policy dominance), the growth engine became private debt.

While the IMF and the rest of the conservative institutions like the OECD etc were pushing their export-led development models they failed to explain to us that this strategy (even if it was sensible for any nation) could not be a blueprint for all nations because it is a fallacy of composition to believe all nations can run external surpluses just because one nation can achieve this state. Clearly, not all nations can run external surpluses.

So economic growth for most nations (the external deficit nations) had to rely on domestic expenditure. That means either private domestic or government sector spending would have to offset the demand drain coming from the external deficits. The IMF never really explain that to anyone. If we conducted a poll I am sure most responses would agree with the proposition that net export growth is possible and desirable.

The point is that with public austerity being preached by the neo-liberal policy makers the only way any growth could occur was with private domestic deficits. There is no other way – it is simple really.

For any level of aggregate demand and national output there are three incontrovertible facts that arise from the national accounting systems we use.

Incontrovertible Fact 1: Government deficit (surplus) = Non-Government surplus (deficit).

Incontrovertible Fact 2: Non-government sector is sum of private domestic sector and the external sector.

Incontrovertible Fact 3: If the external sector is in deficit, then a budget surplus or a balanced budget is always associated with a private domestic sector deficit.

Incontrovertible Fact 4: If the budget deficit is less than the external deficit then private sector will be in deficit overall.

Incontrovertible Fact 5: If the budget deficit equals the external deficit then the private domestic sector is in balance overall.

Incontrovertible Fact 6: If the budget deficit is greater than the external deficit then the private domestic sector is in surplus overall.

Incontrovertible Fact 7: If the private domestic sector is in surplus overall, it is spending less than its income and thus saving.

Incontrovertible Fact 8: If the private domestic sector is in deficit overall, it is spending more than its income and building up debt, running down saving, or selling previously accumulated assets.

Incontrovertible Fact 9: If there is an external deficit, the government and private domestic sectors together cannot reduce their respective debt levels.

Incontrovertible Fact 10: Spending equals income and is the sum of net external spending (exports minus imports), private domestic spending (consumption plus investment) and government spending. A fall in overall spending results in a fall in income (output). A fall in one component of spending can be offset by a rise in another component to maintain existing income levels.

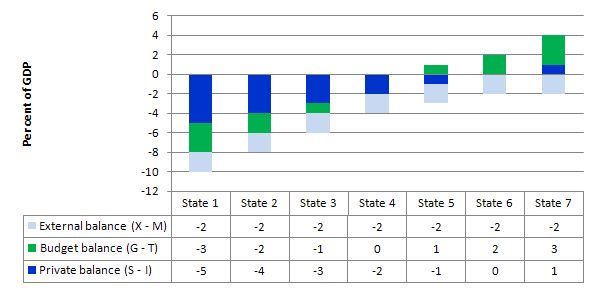

Here is a graph and table to allow you to see the binding relationships between the macroeconomic sectors. A negative (positive) private balance is a deficit (surplus) while a negative (positive) public balance is a surplus (deficit). I have constructed this for a persistent external deficit (negative) of 2 per cent of GDP to provide a control for the different states.

Please note: the relationships depicted are not my opinion, subjective interpretation nor my conjecture. They are fixed by the way we define the national accounts and have to be true by definition. While they don’t indicate causality and you have to infer that from specific contextual analysis these relationships always hold for the different circumstances and should be ground into every economists mind who wants to comment or conjecture about macroeconomic matters.

Many of the comments you will read fall foul of these sectoral balances and promote policies and desired outcomes that cannot all be mutually consistent.

If the financial commentators and journalists wish to remain lazy and parrot statements from economists in their articles and other media commentaries it would be better that these incontrovertible facts become their grist – their “Polly wants a cracker” mantras. For if people who read their stuff started to consider these facts then the policy debate would be on much better footing.

We might still have governments (for ideological reasons) promoting fiscal austerity but then they would have to come clean and admit they were going to damage their economies but that was the price they were willing to pay for smaller government (not that an austerity program necessarily delivers smaller government when measured in terms of the budget outcome).

But I consider it important to understand that the sharpness of the swings in sectoral balances over the last few years has reflected the atypical period that preceded the crisis where growth was fuelled by private debt in the face of fiscal contraction. The return of public deficits – while being held out as something abnormal and shocking and to be eliminated as soon as possible – is in fact, a return to normality.

Yes, the budget deficits are historically “large” in terms of GDP but that is just an overshooting effect which is mirroring the extent of the neo-liberal creation of private deficits. That movement was so extreme in historical terms that the damage that has been caused by its unwinding has created the necessity for an overshoot in the other direction. As growth returns the more normal budget deficits will return and be sustained.

The other overwhelming thing that is obvious when you understand my 10 Incontrovertible Facts noted above is that it will take some years for the adjustment back to normality to be completed and so large fiscal deficits will have to persist.

The danger is that the ideological attacks on the fiscal deficits will derail the process. But when the sectoral balances return to more normal levels in relation to GDP then guess what? We will still have budget deficits and we all better get used to it.

But the parrots continue.

In a recent UK Guardian article (January 31, 2011) – The high deficit, low tax trap – economist Jeffrey Sachs is trying to be reasonable but cannot get beyond his restrictive framework – that the US budget deficit is on an “unsustainable trajectory” and is creating a “mountain of debt that threatens America’s future”.

Polly want a cracker!

The article highlights the tension between the US President’s desire to invest in “education and skills to boost the US economy’s competitiveness” while at the same time allegedly facing a “budget crisis”. Sachs says that the:

The heart of any government is found in its budget. Politicians can make endless promises, but if the budget doesn’t add up, politics is little more than mere words.

The budget always “adds up” to whatever it adds up to. There is no benchmark that it has to “add up” to. But the reality is that it is the “politics” that dominates and attempts to force the budget to add up to particular outcomes which may not be in the best interests of the nation as a whole. At present this political coercion is creating a nightmare for ordinary citizens who are unemployed or dependent on someone who remains unemployed.

Sachs think that the “United States is now caught in such a bind” by which he means that the political ambitions expressed by the President (in the State of the Union speech) are being thwarted because he thinks the budget doesn’t add up and as a result:

… the truth is that both parties are hiding from the reality: without more taxes, a modern, competitive US economy is not possible.

That is not a truth. It is true that “both parties are hiding from the reality” but the US economy can be improved and modernised without the need to raise taxes. Why?

The President’s aspiration to improve the skills and productivity of the US workforce at its most basic level requires that all the workforce is currently working at the potential of their current skill levels. Policies that fail to reduce unemployment now violate that aspiration. So that is why I do not believe the US President is sincere in his desires – they are more politicial posturing than genuine ambition.

If he was genuine he would be acknowledging that the US government could reduce unemployment today with one simple announcement such as:

We will employ anyone at the minimum wage (which we will ensure is increased to meet reasonable social standards) who wants to work. Just turn up at the Job Guarantee depot tomorrow morning and you will be on the payroll. This offer is unconditional and unlimited.

The US government has the fiscal capacity to do that immediately. Then improving funding for education and skill development can follow once everyone is working closer to their potential. At present with almost 17 per cent of labour resources lying idle – there is a lot of slack that can be taken up with a public employment scheme. Then the government can develop further more sophisticated ways of improving skills etc.

But I am continually being told that the problem of unemployment is much more complex than a lack of jobs. To which I respond – no it isn’t. Create the work and unemployment will fall – 1 for 1.

Which reminds me of an interesting article I read this week by British economist John Kay – hose at the nucleus may not have the best view. I don’t normally agree with him but he is interesting nonetheless. In this article he makes the excellent point.

Kay said that:

So when someone tells you something is too complex for you to understand, the usual reason is that they do not really understand it themselves. Sometimes they know that they do not really understand it: often they do not.

For the inquisitive intellectual, few people are as irritating as those whose combination of ignorance and arrogance is so profound that they claim to understand things they do not even know they do not know.

The world of business and finance, which values confidence and certainty, is full of such people. “It isn’t really like that,” they will say; and when you ask what it is really like, they will tell you it is too complicated for you to apprehend. What they really mean, but do not recognise, is that it is too complicated for them to apprehend.

You can continually repeat “Polly wants a cracker – the deficit is unsustainable”. But that doesn’t explain anything. Most of the financial press who daily mouth the neo-liberal mantras about the dangers of deficits etc do not understand the incontrovertible facts noted above. They propose outcomes that cannot possibly be consistent. They introduce falsehoods that reveal their lack of understanding of monetary systems. The conflate and compare different monetary systems which have very different properties and provide governments within them with very different policy opportunity sets.

And the rest of it …

Kay is indeed commenting about the Davos meeting where all these self-proclaimed “special” people gather in luxury to prognosticate about the plight of the unemployed without actually knowing (or admitting) that the policies they propose create and entrench that unemployment.

Kay says:

The bad financier, or businessman, like the bad scientist, pursues complexity almost wilfully because he believes such complexity demonstrates his knowledge and sophistication. So the blind lead the blind through the mysteries of structured financial products and the jargon-ridden thickets of corporate strategy … Consultants describe the business world in language – and, of course, PowerPoint presentations – whose elaboration disguises the banality of the thought. Real understanding lies in finding simplifications that bring order to disparate facts … People in the middle of events often know less about them than those watching from the outside, which is why interviews with senior business figures inform us about what these people think rather than what is happening. The panels of grandees at Davos who pronounce on the future of the world may know less about the subject than spectators on the lower slopes.

I liked the tenor of those thoughts and the propositions Kay entertained and they can be easily extended to the mainstream economic commentators and “Harvard” professors.

Which includes Sachs …

He claimed that while the US President was on sound footing to promote the pursuit of “an educated workforce and modern infrastructure” he:

… lost touch with reality when he turned his attention to the budget deficit. Acknowledging that recent fiscal policies had put the US on an unsustainable trajectory of rising public debt, Obama said that moving towards budget balance was now essential for fiscal stability. So, he called for a five-year freeze on what the US government calls “discretionary” civilian spending.

The problem is that more than half of such spending is on education, science and technology, and infrastructure – the areas that Obama had just argued should be strengthened. After telling Americans how important government investment is for modern growth, he promised to freeze that spending for the next five years!

There’s the mantra … creeping into the commentary – fiscal policies had put the US on an unsustainable trajectory of rising public debt. What exactly is an “unsustainable trajectory”? Why does rising public debt matter? What benchmark should we use to assess that?

The answer is that there is no solid footing for this terminology. A rising budget deficit may be entirely sustainable if it is filling a spending gap left by increased non-government saving. With an external deficit not about to be reversed any time soon in the US, a rising budget deficit is the only way the country is going to rebalance the massive private indebtedness that threatens financial stability and is constraining economic growth.

The neo-liberals promoted a growth strategy on the basis of a deregulated financial sector which poured credit into the private sector. The greed and dishonesty of the financial engineers (some) meant that the credit binge was increasingly widened into private households who didn’t have a hope in hell of paying the debts back but with “pass the parcel” (aka securitisation) the risk was continually being shuffled around and so individual shufflers could make their fast buck and pass the risk on.

Be careful what you wish for! The other side of that private debt binge are the historically large public deficits that followed the inevitable meltdown. The amount of private debt that is still out there which could be classified as being at risk is huge in the US and elsewhere. The banking system is still shaky. What does that tell you? Answer: it tells me that we better get used to on-going and historically large public deficits for many years to come before normality returns.

The larger the mess, the longer the clean up.

However, there is nothing unsustainable about this for a government that is not financially constrained. They can support the deficits for as long as is necessary to support growth and the private deleveraging process. That is the only sustainable option facing the US at present. Trying to retrench these deficits is the unsustainable policy option because it will undermine the private deleveraging process, entrench even higher unemployment and ultimately cause an even larger crash than the 2007 crisis.

That was my message when I wrote the blog last February (2010) – Chill out time: better get used to budget deficits – and it remains my message. I think the predictions I have consistently made over the last few years in this blog (and prior in my academic work for many years) have been accurate and contrary to the predictions of mainstream economists.

Sachs further reveals his biases when he writes:

That contradiction highlights the sad and self-defeating nature of US budget policies over the past 25 years, and most likely in the years to come. On the one hand, the US government must invest more to promote economic competitiveness. On the other hand, US taxes are chronically too low to support the level of government investment that is needed.

The US government does not need to increase US taxes to “support the level of government investment that is needed” unless Sachs means that the level of public demand relative to the available real resources and non-government demand will outstrip the capacity of the production sector to respond in real terms.

We all know that is not what he is referring to. He thinks the US government has to “raise funds” to pay for the investment so that it can avoid “raising funds” by issing debt which is on an unsustainable trajectory.

Once you make one error of reasoning then all the error dominoes fall into place – once you make the erroneous conclusion that the US government is financially constrained and that its debt levels cannot be sustained then you are forced to conclude that if the government is to spend more it has to raise taxes.

The US government might have to raise taxes after it spends more on education and infrastructure but that will have nothing to do with “funding” the spending. It might be that the sum of public and private spending is too large relative to the capacity of production to respond in real terms. That is, it might push the economy beyond the inflationary barrier. The taxation then ensures that aggregate demand is consistent with the real capabilities of the economy.

Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

At present, there is so much excess capacity available in the US it is hard to see it hitting an inflation barrier soon. In fact, inflation is well below any implicit Federal reserve target (lower band).

By parroting the mainstream mantras about unsustainability Sachs is then forced to conclude:

The economic and social consequences of a generation of tax-cutting are clear. America is losing its international competitiveness, neglecting its poor – one in five American children is trapped in poverty – and leaving a mountain of debt to its young. For all the Obama administration’s lofty rhetoric, his fiscal policy proposals make no serious attempt to address these problems. To do so would require calling for higher taxes, and that – as George HW Bush learned in 1992 – is no way to get re-elected.

The tax-cutting of the past regimes in the US have nothing to do with the parlous state of its nation outlined by Sachs. The problem has been an unwillingness to expand the budget deficits over the last 20 years to permit appropriate investment in human capital, urban infrastructure, and education and training. It is the dominance of the “free market” ideology of the American political lobbies that has created the problem not a lack of tax revenue.

I won’t comment further on the “mountain of debt to its young – Polly wants a cracker” statement. Please read my blogs – The rising future burden on our kids and Our children never hand real output back in time – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

My friends in Northern Queensland survived the Category 5 Yasi last night although there is extensive property damage and an estimated $A1 billion hit to GDP in the coming months. The Australian Prime Minister didn’t wait to see if anyone was dead or how much damage there was before she told the press last night that the Australian government would stand by the people of Queensland in their time of need (good) and that it would cut other spending items to help repair the extensive damage so they could keep their budget surplus goal on track”.

Polly wants a cracker!

With each of the successive natural disaster hitting our GDP in the last month or so, the automatic stabilisers will continually work against that goal anyway! The government should pursue an increased budget deficit right now to ensure the damaged areas are restored and people have work.

That is enough for today!

“Polly Wants A Cracker” appears in the track “Polly” in Nirvana’s album Nevermind as well.

Well put, Bill. One thing I would add: those who say the government can’t be trusted to spend money wisely, even though they may (often) be right, don’t seem to have noticed the extreme folly involved in the spending fueled by the increase in private sector debt over recent years. Most of it has gone into a huge real estate bubble. Very little of that has been productive – some must have been, since new homes have been built, and others have been extended or refurbished with borrowed money, but most of it simply increased the price of existing housing stock. Governments haven’t cornered the market in stupidity.

“we need more commentators who will ask the right questions – challenge the politicians and their lackeys to explain what they mean rather than talk as if it is too complex for us to comprehend.”

Unfortunately, the commentators who are in a position to ask the questions are the lackeys, or they wouldn’t be commentators for long.

Oh, and all this US President does is posture. When I heard Mubarak say he wouldn’t resign, I said he will resign. Maybe he won’t, but I’m the same with obumer, when I hear him say something I think the opposite. I don’t pay any attention to anything the man says.

Get rid of negative gearing in Australia and the real estate problem will be mostly solved.

Thanks

@ Alan – negative gearing doesn’t stop real estate bubbles. A 100% land tax does (with most/all other taxes abolished).

(abolishing negative gearing that is)

Spadj,

Land tax as in what the Georgists proposed ?

Bill,

Your graphic illustrates sectoral balances for mythical states. Could you provide real world numbers for several countries for a given year (or a link where I can find this data)?

Thanks

Pollywanacraka is also a track on Public Enemy’s “Fear of a Black Planet” album.

Bill, assuming an external deficit, if only the government can create net financial assets for the private sector, is all private debt ultimately paid for by the government anyway? That is, could private debt be considered government spending brought forward?

Thanks.

Talking of Polly wanting crackers (or should that be just crackers). Here we have an interview with the new Shadow Chancellor in the UK Ed Balls (who incidentally did the same PPE degree as the UK Prime Minister so perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised).

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-12275815

He starts waffling on about Barro-Ricardian equivalence about half way through the interview to try and explain the Q4 GDP drop.

So another front-line politician that believes in the Tooth Fairy. We’re doomed.

Bill, all else being equal, would you favor the issuance of debt, or non-issuance of debt for government deficits? Is the savings-vehicle aspect of running deficits and issuing debt helpful to keep excess savings out of the private investment casino, or on the other hand, is the ongoing expense of paying interest out of the government’s slice of GDP regressive and costly? Is there a danger of such debt becoming significantly more onerous when interest rates go up, as they would under conventional policies?

I get it that spending equals income and that the deficit in countries like the US, UK and Australia is a more or less arbitrary number.

What I don’t understand is the upside to austerity measures and attempts to achieve a government surplus. Does it somehow benefit big business, the wealthy and those in power? Otherwise why on earth would politicians (who surely know that their governments are not revenue constrained) persue these policies?

Would a surplus significantly increase the value of a currency in relation to other currencies? Even then that would only make imports relatively cheaper while making exports more difficult.

Does a certain level of unemployment encourage some internal competition for jobs that leads to overall better productivity/higher GDP?

I just don’t get why politicians are attempting to mislead the masses.

Skeptic,

My theory about the “bond market vigillantes” is that is an intentional bluff to force governments into auterity, which will actually mean those governments issue more debt, for longer and on better terms for the bond market.

Skeptic:

Please start with https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=277, and follow other links to related blogs and peruse Bill’s Archive page, which describes how austerity measures maintain unemployment, keep wages down and result in an increasing fraction of national income flowing to capital and business. So austerity benefits those at the top by beggaring those in the middle and below. Of course, this policy is the REAL unsustainable policy in the long run. It resulted in the current crisis, many past crises, and also more extreme events such as revolutions. It sows the seeds of it’s own demise.

A little off topic but I would like to get everyone’s thoughts on this:

Inequality, leverage and crises

http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/6075

IMO and in the end, too much debt is the problem, whether gov’t or private.

hi skeptic

“What I don’t understand is the upside to austerity measures and attempts to achieve a government surplus. Does it somehow benefit big business, the wealthy and those in power? Otherwise why on earth would politicians (who surely know that their governments are not revenue constrained) persue these policies?”

because they the politicians and the economists that advise them are all lousy accountants. they wouldnt know a sectoral balance if they tripped over one.

“Would a surplus significantly increase the value of a currency in relation to other currencies? Even then that would only make imports relatively cheaper while making exports more difficult?”

the best way to destroy the value of the currency is to make sure that there is rising tide of the unemployed with no demand for the currency, by running a budget surplus in the worst private sector down turn in living memory. ultimately the value of the currency is determined by the productive potential of the economy, despite it being the play thing of currency traders.

“I just don’t get why politicians are attempting to mislead the masses.”

they havnt got a clue skeptic. i have the fortune or is it misfortune to talk to our political leaders on a regular basis, and you should see the expressions i get when i try to explain to them the reality of sectoral balances. but i must say some of the more independent thinkers are prepared to listen, and i do give them regular homework reading in the form of bill’s wonderfull blog pieces. but its a battle. the whole notion of this household budget analogy is heavily ingrained in our political leaders. there is a natural prejudice towards it, even accounting logic finds difficult to overcome

our political leaders are still stuck in the 19th and 20th century gold standard , brief cases full of cash view of the world. they have no comprehension of the modern reality of binary data held in the form of a spread sheet, and virtually shifting or creating accounting balances . hell, most of them wouldnt know how to create a spread sheet in the first place.

i suspect we might have to wait till todays 13 year old, tech savey, virtual reality kids become tomorrows 40 year old economic architects before we see ideas such as mmt come to the fore

the neo cons, say we cant raise taxes to cover the gap, and they are right,

but cutting spending wont be the answer either, because it will becaome an operational impossibility in terms of financing the welfare system

the solutions easy, run larger more permanant deficits,

budget surpluses are going to be a historical artifact in the not so distant future due to demography, and the balance sheet logic of mmt will prevail.

Thanks FED UP, interesting item. A bit mono in a macro world. The increase in debt is just the 95% wanting to live like millionaires. Leverage in a world of asset inflation is easy money making. For sure most of us wont get rich on wages so what is left? Leverage. I have worked for many high net worth families and my observation is at some stage a family member got very lucky with a risk and made a bucket load launching them into the 5% of the very wealthy. In my view its not leverage but luck that makes the big money. Books are written about the winners in the 5%. For every one of them there must be hundreds that loose everything via leverage. More research about why the losers lost everything even though many of them did exactly what the winners did is needed so the masses can inform themselves about what is being risked by leveraging up. For more on the debt story have a look at Steve Keen’s debtwatch site. Steve K is convinced deleveraging is the elephant in the room.

mahaish, that would be depressing if it was not obvious! I have suggested that Bill’s strong ideas be reduced to ultra simple explanations because many politicians are very ordinary folk (as it should be). Its the ordinary folk that promote popular ideas not the Policy Industry. Politicians will respond to the ideas popular with the ordinary folk then Policy Climbers find ways to champion the popular ideas. Paying off deficits is a typical example. It does make sense to the ordinary folk so the politicians and Policy Climbers get on the bandwagon. To change policy aim at the masses with simple ideas a grade 7 child could explain to Mum and Dad in 2 minutes or less. Mastering simplicity may be the greatest challenge for those who would change policy. This simplistic explaining may be beyond anyone trying to impress the Policy Industry itself.

I have not commented on Bill’s post as I am still getting my head around the “incontrovertibles”. Cheers Punchy