My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

My response to a German critic of MMT – Part 2

This is the second part of my response to an article published by the German-language service Makroskop (March 20, 2018) – Modern Monetary Theory: Einwände eines wohlwollenden Zweiflers (Modern Monetary Theory – Questions from a Friendly Critic) – and written by Martin Höpner, who is a political scientist associated with the Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung (Max Planck Institute for Social Research – MPIfG) in Cologne. In this part we discuss bond yields and bond issuance. I had originally planned a two-part series but the issues are detailed and to keep each post at a manageable length, I have opted to spread the response over three separate posts. In Part 3 (next week) we will discuss inflation and round up the evaluation of his input to the debate.

The previous parts in this series:

1. My response to a German critic of MMT – Part 1 (March 26, 2018).

Now to detail.

To ensure these blog posts do not become too long, I decided not to quote his original German.

So, when I quote Martin Höpner using quotation marks “”, I am providing my translation, and, given my German to English is not perfect, nuanced errors in translation and interpretation (usage) are possible.

I have in the last two days, though, had my translation checked with a fluent German speaker and writer to minimise possible errors.

Bond yields …

Martin Höpner’s second major issue, which he considers to be “the heart of the problem” is that he claims MMT adopts an “overly optimistic description of political freedom”.

What appears to be his problem is that while MMT is fine in his estimation – in theory – it has limited application in the real world because other (political, practical) issues intervene.

Remember that MMT does not intend to be a ‘theory of everything’ and certainly does not hold itself to provide deep insights into questions that political scientists might concern themselves with.

MMT is about the monetary system – how it works, what opportunities the currency-issuer has to advance well-being, what constraints there are to hinder that quest, and similar foci.

To make his case in this regard, Martin Höpner first explores the question of bond yields, which he rightly notes are under the control of the government should they choose to exercise that capacity.

As I have noted many times, the belief that a currency-issuing government can be put under siege by the private bond markets via bond auctions is false.

The central bank can always control yields on government debt at whatever maturity they choose by standing ready to purchase whatever volume is required to ensure the private bond market desires are subjugated.

If this is prohibited by current laws or regulations then the legislative capacity of the government can easily be amended if it was deemed to be a problem.

Even when the laws do not change, as in the Lisbon Treaty banning bail-outs of Eurozone Member States’ deficits, the ECB has easily found a workaround using its currency-issuing capacity to purchase massive volumes of government debt in secondary markets, and, in doing so, control yields at its will.

Please read my blog post – Operation twist – then and now – for more discussion on this point.

But Martin Höpner’s point is that while governments might be able to do this, political and other considerations would make it undesirable for them to act in this way.

In other words, there is a difference between what can be done “in principle” and what should be done in practice.

Ok! The world is complex.

The question is whether it is desirable for people to understand, initially, that governments do have this capacity or whether keeping them in the dark and believing in the misinformation put out by mainstream economists is preferred.

He uses an example of the pre-Eurozone Member States, when they still had their own currencies, and points out that there were “considerable differences between the government bond spreads”.

Yes, there were. And so?

He then asks:

Did the countries with high risk premiums fail to recognise their basic ability to minimise them?

First, he seems to ignore the fact that these countries were in the Bretton Woods system until 1971 (and beyond until it was officially scrapped when the Smithsonian Agreements failed on February 14, 1973).

After most of the rest of the world decided that floating exchange rates were more desirable as it freed monetary policy from having to defend the agreed parities, the EEC Member States persisted with various dysfunctional fixed exchange rate arrangements – the Snake in the Tunnel, the Snake, the EMS and then the ultimate ‘fixed exchange rate’ system – the common currency.

Each one of these arrangements proved to be unworkable in the sense of allowing the governments to unambiguously advance the well-being of their people.

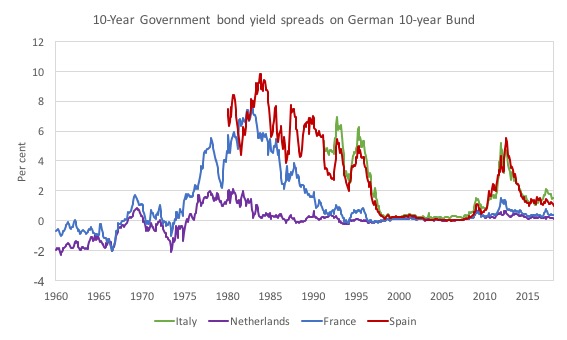

Here is a graph of the 10-year government bond spreads against the German 10-year bund for France, the Netherlands, Italy (from 1991), and Spain (from 1980) for the period 1960 to January 2018.

There was obviously significant variability especially in the period following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system and prior to the adoption of the common currency. The variability reentered the picture after the GFC and before the ECB went to work controlling the spreads in May 2012 and onward.

The obsession with fixed exchange rates among the European nations is in no small part due to their decision to introduce the Common Agricultural Policy in 1962.

This complex system of cross border price fixes would have been administratively impossible to manage without relative currency stability. As it was, the currency variations within the Bretton Woods system led the European Commission to introduce a complex system of so-called ‘green exchange rates’ or simply ‘green rates’, which sat underneath the official exchange rates.

These rates were designed to insulate farm prices from the fluctuations in the market exchange rate. They were set at the parities that ruled prior to the realignment of the French and German currencies in 1969, after major instability in World markets occurred and the Bretton Woods system was entering its death throes.

This approach added layers of complexity onto complexity – a typical European Commission action.

The ‘green rates’ were accompanied by the system of Monetary Compensatory Amounts (MCAs), which were introduced to fix competitive departures arising from fluctuations in exchange rate parities – which critics believed constituted a violation of the EEC principle that prohibited any duties being imposed on trade within the common market.

That didn’t stop them of course. Nothing much has changed. Rules are broken in Europe when convenient.

The point is that the spreads on EEC Member State bond yields pre-Eurozone were in no small part due to discretionary decisions taken by the respective central banks nations with external deficits in an attempt to attract capital inflow (mostly away from Germany).

The Bundesbank historically ran a tight monetary policy because of its obsession with low inflation and this forced its trading partners to endure higher unemployment than they desired or which were suitable given the state of domestic demand in their economies.

The weaker currency EEC nations – France, Italy, the United Kingdom (after 1971) – were forced to accept the restrictive Bundesbank monetary policy settings or else face major capital outflows.

But they were continually up against currency pressures to devalue (under the fixed arrangements and with the Bundesbank more or less refusing to intervene symmetrically), so at times they had to push rates up well above the German rates to head of impending currency crises.

The history of the EEC is littered with these episodes.

So it is hardly a demonstration of the practical aspects of MMT to draw attention to this period of European history.

Whether the nations knew their central banks could intervene in the same way the US Federal Reserve intervened during Operation Twist in February 1961 is beside the point. Of course the central bankers knew they could do the same if they wanted to.

But their policy imperative, given their governments had signed them up to an ‘unworkable’ fixed exchange rate system was to drive the spreads up to offset capital outflow.

The logic of their misconceived choice to tie their currency up in this way demanded they do that.

The consequences were obvious – a recession bias, elevated levels of unemployment, and ultimately, increased speculative attacks on their currencies necessitating period devaluations following a currency crisis.

None of that tension has really gone away under the common currency. It is just that ‘internal devaluation’ has replaced the discretionary realignments pre-euro and central bank can no longer control capital flows in the way they did when their governments were sovereign.

So I found this ‘criticism’ of MMT to be rather facile at best.

Martin Höpner’s own assessment is that the governments in question did “recognise their basic ability to minimise” the spreads but:

… the point was that there were, in fact, other constraints in the design of risk premiums, which are insufficiently captured by MMT due to its focus on the unlimited ability of the central banks to raise funds.

This is a non-criticism.

Remember, again, MMT is not a ‘theory of everything’!

MMT proponents fully recognise that governments may choose to deny their own capacities in search of other objectives – political, ideological or whatever.

That insight is repeated throughout our work – the role of voluntary constraints juxtaposed against the intrinsic characteristics of the monetary system.

Which raises an interesting point that Martin Höpner does not seem to appreciate.

Politics is intrinsically a part of the interaction between the citizens and the elected representatives. Where voting occurs to elect the government, ultimately the politicians have to introduce policies that resonate with the expressed desires of the voters.

Clearly, a dislocation can occur, which usually brings down the elected government at the next election.

History shows us that governments can become captured by sectional interests (the ‘few’), whose ambitions are incongruous with the advancement of the well-being of the ‘many’.

In that case, the political message is massaged strongly through framing and language, a topic I have written a lot about (for example, see recent Journal of Post Keynesian economics article written with Dr Louisa Connors).

That framing and language serves to obscure the intrinsic characteristics of the monetary system and thus restrict the awareness in the public debate for what policy options are available and the likely consequences of each alternative.

Please read my blog posts under the – Framing and Language category – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that by, initially focusing on and emphasising the intrinsic characteristics of the monetary system, and no other body of work does that, MMT strips way the veil of neo-liberal ideology that mainstream macroeconomists use to restrict government policies.

We learn that these constraints are purely voluntary and have no intrinsic status.

This allows us to understand that governments lie when they claim, for example, that they have run out of money and therefore are justified in cutting programs that advance the well-being of the general population.

By exposing the voluntary nature of these constraints, MMT pushes these austerity-type statements back into the ideological and political domain and rejects them as financial verities.

I am surprised that Martin Höpner, as a political scientist, seems oblivious to this veil of ideology and the purpose it serves.

MMT thus broadens the understanding of the policy possibilities for those who come into contact with it. It is a body of work that enhances our democracies.

By exposing these intrinsic characteristics and lifting the ideological veil that politicians hide behind, MMT becomes a broadening force in the public debate.

Sure, as Martin Höpner notes, governments have “other constraints in the design of risk premiums”, which may or may not prevent them politically from driving bond yields to zero.

But what are those constraints? An understanding of MMT quickly sorts out the financial considerations from the ideological.

People quickly realise that bond issuance does not fund government deficits, even if the accounting arrangements make it look as though it does.

People quickly realise that the central bank does not need stocks of government debt to manage their liquidity operations (reserve management) as part of their desire to target a specific short-term interest rate.

They can just pay an interest return on excess overnight reserves or take the Japanese route and allow overnight rates to fall to close to zero.

When a government tells the people that the bond markets determine bond yields and so they have to cut spending because the investors are losing confidence in the government’s ability to pay – which is a recurring theme in governments attempting to justify the unnecessary and damaging imposition of austerity – the depoliticisation strategy (blame the bond markets) – an understanding of MMT allows people to recognise this sort of justification as a non-justification.

We quickly recognise it as an ideological statement. A ruse to pursue policies that have no ‘financial’ basis in terms of capacity to pay or whatever.

It allows the population to appreciate that bond issuance is really about corporate welfare – providing a risk free asset upon which private financial assets can be priced (for risk) and which can be used as a safe haven when there is uncertainty in the private financial markets.

An understanding of MMT thus changes the questions that we ask of our politicians. It broadens the debate. It prevents politicians from invoking faux constraints to justify actions which are detrimental to the ‘many’.

That is an empowering thing.

Sure enough, governments might have reasons for preferring a positive spread on their relative bond yields. But those reasons would have to become transparent and the public would be better placed to evaluate the veracity and reasonableness of those justifications as a result of the work by the MMT proponents.

The other issue that Martin Höpner has in relation to the way MMT discusses government bonds is that we allegedly ignore other useful purposes that bond issuance may serve and which would require positive yields on the bonds.

He fully understands that the sale of government bonds do not have a ‘financing’ function.

But there are other useful functions, which we apparently ignore.

Martin Höpner writes that government bonds provide a means by which “citizens can place their savings”.

This point is clearly recognised by all the major MMT proponents. If you go back to our early contributions in the 1990s, you will see we discuss the way in which a government can encourage thrift by issuing a bond rather than leaving excess reserves in the system earning zero returns.

For example, please read the blog posts:

1. A simple business card economy (March 31, 2009).

2. Barnaby, better to walk before we run (February 9, 2010).

3. Some neighbours arrive (February 15, 2010).

Martin Höpner believes that this ‘function’ means that:

… surcharges have to compensate fairly for inflation and also for uncertainty about future inflation changes – for inflation risk. In addition, savers want to preserve the value of the money tied up in the financial asset not only with regard to domestic but also to foreign goods (travel, imported goods). Risk premiums must therefore not only charge inflation risk but also exchange rate risk.

And if the central banks ignored this and “continued to press down interest rates on government bonds” then the “bonds would lose their function as a fair offer to the domestic savers.”

Which is another non-criticism as far as I am concerned.

Think again about what I wrote above about framing and language and exposing the veil of ideology etc.

The same point applies here.

Obviously, longer term financial assets (public and private) will tend to generate yields that ‘price’ in the sort of risks that Martin Höpner is talking about here.

The further we go out along the yield curve – to longer maturities – the greater will be the uncertainty differential demanded by investors.

There is nothing revelatory about that!

But once citizens understand that the bonds they are buying are not required to fund government deficits then a debate opens up as to what function they might actually serve and whether those functions can be better served in other ways.

Again, an enhancement of democratic choices is made possible.

It is easy to demonstrate that government bonds are mostly serving a ‘corporate welfare’ function as noted above.

Please read my blog post – The bond vigilantes saddle up their Shetland ponies – apparently – for more discussion on this point.

See also – There is no need to issue public debt (September 3, 2015).

While I am supportive of workers being able to save (risk manage their futures) in a safe way, that doesn’t justify the massive corporate welfare that accompanies the issuance of public debt.

It is often argued that if superannuation and life insurance companies were unable to purchase government debt then they would struggle to match their long-dated liabilities with appropriate returning assets.

Further, the claim is that eliminating the government bonds market, retirement planning would become highly uncertain and risky.

What is not often understood is that government bonds are in fact government annuities.

Do the proponents of on-going government bonds really want the private sector to have access to government annuities rather than be directing real investment via privately-issued corporate debt, as an example?

This point is also applicable to claims that government bonds facilitate portfolio diversification. Why would we want to provide government annuities to private profit-seeking investors?

This is in the ‘privatise returns, socialise the losses’ terrain.

Further, if the justification for continued government bond issuance is to provide a method of retirement subsidy for workers, what are the relative benefits and costs of this choice against more direct methods involving more generous public health and welfare provision and pension support?

You see here that the questions we ask are very different once we understand MMT.

We break clear of the shackles that the ‘bonds fund deficits’ lie imposes on us and start questioning the status quo.

We would soon realise that there is a much more effective way to provide a risk-free savings vehicle for workers.

The government could create a National Savings Fund, fully guaranteed by the currency-issuing capacity of the government, which could provide competitive returns on savings lodged with the fund.

There would be no public debt issuance (and the associated corporate welfare and government debt management machinery) required.

The government could meet any nominal liabilities that would arise from this system at any time.

We discuss this sort of option in detail in our new book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017)

Conclusion

In Part 3 of this response we will discuss Martin Höpner’s concerns about inflation.

Reclaiming the State – Big Discount

Pluto Books has gone mad this Easter.

All their stock is being offered at a 50 per cent discount, which is better than the author’s discount I can get normally.

That means you can purchase our new book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World – online, for half price (and the Paperback version comes with a free e-Book).

The offer ends on April 9, 2018.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The government could create a National Savings Fund, fully guaranteed by the currency-issuing capacity of the government, which could provide competitive returns on savings lodged with the fund.”

for individuals.

I have asked everybody raising this point about bonds with interest attached.

(i) why do the instruments need to be tradeable?

(ii) why do the instruments need to be transferable?

(iii) why do the instruments need to be available to anybody other than a resident individual?

The currency is a 0% bearer bond that is tradeable, transferable and holdable by entities other than resident individuals. It’s value varies in terms of other ‘bonds’ holders may choose to hold. Why is there a need for any other state issued instrument?

Yet to get anything like a rational answer to that one.

On the point about Common Market (and then EC, and EU) countries needing fixed exchange rates in order to operate CAP, I wonder.

Other than our brief and disastrous experiment with joining the ERM, the UK hasn’t had fixed exchange rates since the 1970s, and yet we have somehow “managed” being in the EC, and then the EU. (Not saying the CAP is particularly good for us though. And by the way, I don’t think I heard it mentioned in the EU Referendum campaign by either side).

Neil Wilson questions the need for any state issued liability other than zero interest yielding base money. Warren Mosler and Milton Friedman also opposed any sort of interest yielding government debt. For Mosler, see second last paragraph here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/warren-mosler/proposals-for-the-banking_b_432105.html

and here:

http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP37-MoslerForstater.pdf

Re Friedman, see under his section II: “Operation of the proposal…” here:

https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/friedman_images/Collections/2016c21/AEA-AER_06_01_1948.pdf

However, strikes me it would be an idea to allow departures from the Mosler/Friedman idea in an emergency: i.e. where there was a serious outbreak of irrational exuberance, and demand needed to be reined in in a hurry. That is, given that outbreak, there’s a good case for letting a central bank wade into the market and borrow at above the going rate for a while.

“That is, given that outbreak, there’s a good case for letting a central bank wade into the market and borrow at above the going rate for a while.”

The central bank can’t borrow. It is the source of money.

Why do anything like that rather than simply restricting what banks can lend money for? Calling in loans dampens enthusiasm very quickly.

“Why do anything like that …”

Back to the E-series bonds during WWII. The government was paying wages for war production, but didn’t want the wages spent on consumer goods, which would divert effort from war products. Borrowing the paid wages out of the economy and promising to replace them later, at a better time, seemed to be useful. No problem with depleting reserves, because there were going to be more wages paid tomorrow.

Neil & Mel et al- Non-tradeable, non-transferrable instruments or Bill’s National Savings Fund are restricted forms of government debt. They’re pretty much the same idea as US Savings Bonds / War Bonds. The idea during WWII was as to provide an attractive means of deferred compensation, unforced savings, giving higher interest to individuals than the controlled, lower interest rate on Treasury Bonds available to banks or investors. Both rates, the high “retail” and the low “wholesale” rates were used to control inflation in different ways.

The restrictions and the further restriction that savings bonds could not be used as collateral for loans was a means to deaden the money during the high spending of the war, deferring it to peacetime. By the end of the war, they were a major part of the US National Debt, the measures were largely successful. They had a pretty good idea what they were doing back then. A lot better than now!

That being said, there is a limit to the power of such restrictions. Unless it is a Secret Savings account or bond, it is going to improve the holder’s credit rating – a bank or a loan-shark is going to be more willing to lend to someone with a million in their account, in bonds, than to someone without.

One can argue that some low positive rate on bonds or interest on reserves is sensible – some of the “corporate welfare” isn’t extravagance as it goes to the nuts and bolts of running a bank, arguably that is a good enough reason. Of course I generally agree, I’m just reaching.

Great blog!

Book bought!(yes late for me)

One thing I stuggle with is that france,italy,uk, being forced to accept restrictive german monetary policy or else face capital outflows. How can francs,lira,pound ever leave their respective banking systems.I am having a hard time conceptualising what a capital ‘outflow’ actually is.

Also even in a freefloating non pegged currencies(i take it europe all pegged to the deutschmark post bretton woods) isn’t this still possible now?

“How can francs,lira,pound ever leave their respective banking systems.I am having a hard time conceptualising what a capital ‘outflow’ actually is.”

There is no such thing in a free-floating exchange rate system. That’s why it is there – it prevents a drain of fiscal capacity.

Instead what happens is the terms of trade alter. You get fewer imports for your exports and currency.

The problem we have is that we still have a Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate financial system trying to manage a system that works on terms of trade and pass through.

For example if my economy is struggling and there is ‘capital flight’ and my currency is falling (which means everybody else’s is going up) I can simply refuse licences to import, say, Gold into the nation. All of a sudden I’ve eliminated a load of foreign sales and domestic purchases that have no public purpose and reduced the import value relative to the exports. Foreign nations see that a fall in the domestic currencies results directly in a loss of sales and may take intervention action to reduce the strength of their own currency.

Nearly all the problems are down to seeing things in money terms, not real terms and refusing to look at the system in the round – the impact on export nations as well as import nations.

“By exposing the voluntary nature of these constraints, MMT pushes these austerity-type statements back into the ideological and political domain and rejects them as financial verities.

I am surprised that Martin Höpner, as a political scientist, seems oblivious to this veil of ideology and the purpose it serves.

MMT thus broadens the understanding of the policy possibilities for those who come into contact with it. It is a body of work that enhances our democracies.

By exposing these intrinsic characteristics and lifting the ideological veil that politicians hide behind, MMT becomes a broadening force in the public debate”.

Great stuff!

It’s precisely those pivotal attributes of MMT which make it so valuable – indeed indispensable. Whatever the more marginal, inexpert, reservations and doubts I personally have had (and still have), they’re massively outweighed by its virtues, which Bill so eloquently sums up.

Höpner’s criticisms seem to take-on an aspect of being mere quibbles in comparison.

“People quickly realise that bond issuance does not fund government deficits, even if the accounting arrangements make it look as though it does.”

Could someone please explain this statement?

“As I have noted many times, the belief that a currency-issuing government can be put under siege by the private bond markets via bond auctions is false.”

Let’s say bondholders as a class have decided to quit the local currency because they believe the government’s MMT policies will debase the currency.

So they sell their bonds to the government.

Firstly, it has to choose whether it allows bond prices to drop and yields increase, with economy wide implications or it holds yields, pumping more money out in the process.

Secondly, the bond holders take their money and run for the exit, seeking refuge in other currencies, putting the local currency under severe pressure, with the attendant inflationary consequences.

Seems to me that the government is put under siege if it wants to protect the value of the currency and contain inflationary pressures.

I believe the answer is here: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=35685

Haven’t read it, but it has been touched upon since. Reading it next.

Henry, the scary story you are worried about is just as true as most other scary fairy tales. As in it is not true at all for a currency issuing government.

“Let’s say bondholders as a class have decided to quit the local currency because they believe the government’s MMT policies will debase the currency.

So they sell their bonds to the government.”

First of all, bond holders do not have the right to cash in their bonds ahead of time. Bonds are a contract that pays out on a certain date. That is kind of the reason that bonds are issued in the first place- they are not like on demand bank deposits. People who purchased the bonds can not demand on their own to sell them back to the government ahead of time, unless the government is willing . They may be able to sell them to someone else ahead of time at whatever price the market determines but then that party has to wait until the specified term is up to redeem them.

“Secondly, the bond holders take their money and run for the exit, seeking refuge in other currencies, putting the local currency under severe pressure, with the attendant inflationary consequences.”

Since bond holders can not just take the money they loaned to the government for a certain time period and run, this is another fairy tale that you should not worry about. But perhaps they find a second party to sell their bonds to and then exchange the proceeds into a foreign currency. At this point maybe your first point is a possible concern-“Firstly, it has to choose whether it allows bond prices to drop and yields increase, with economy wide implications or it holds yields, pumping more money out in the process.”

So what if the price on already issued bonds drop? All the government has promised is to pay off the bond when it becomes due. Maybe for future bond issues the nominal yield increases? Well MMT holds that the sovereign currency issuing government does not ,for any economic reason, need to issue bonds in the first place. And if they do decide to issue bonds they can set the interest rate at whatever level the government decides it wants to promise. And people can choose to buy those bonds at that interest rate or not- it doesn’t matter.

“Seems to me that the government is put under siege if it wants to protect the value of the currency and contain inflationary pressures.” Seems to me that a country that can produce products that others desire and is willing and capable to levy and enforce taxes in its currency will never have to worry that the foreign exchange value of its currency will get too low. A lot of times the worry is that it is too high.

“Since bond holders can not just take the money they loaned to the government for a certain time period and run”

Generally they can. There is usually an offer of last resort in the system that requires the government sector to convert the bonds to currency. For example the UK Gilt marker has a HM Treasury backstop for the GEMMs to allow them to maintain a market. So you can always get cash for your gilts.

But that is all beside the point. QE has demonstrated in droves that none of this ever happens. Currency is a bond from a foreign holders point of view, so all there can ever be is a portfolio reconfiguration from term bonds with interest to permanent bonds without interest. And that action results in a reduction of income into the economy. In other words it is an additional tax on capital owners.

The result is a search for yield which drives asset prices up, not down. As we saw with the QE process.

The market is servant, not master. Issuing government bonds at interest suppresses other asset prices and raises their yield.

Jerry Brown,

If bondholders decide to quit their government bonds en mass this will drive down prices and yields up in secondary markets. This may interfere with the government’s preferred interest rate path. The government may enter the secondary markets and start buying bonds (a bit like QE). Then the bondholders take their money and sell the local currency. This is entirely feasible.

And the government cannot set interest rates on its own. It takes two to tango. Supply and demand. Sure it can create all the money it wants, but if it frightens private money holders, the game changes.

“Seems to me that a country that can produce products that others desire and is willing and capable to levy and enforce taxes in its currency will never have to worry that the foreign exchange value of its currency will get too low.”

A very big “if”. More self serving thinking. Life isn’t that straight forward.

The only comment of yours that has weight, I believe, is the fact that there may be no bonds in public hands. In which case, private money will be held in other forms and if the private money holders decide that they don’t like the government’s policies, they can quit the currency – and around we go again.

Unless you are talking about a fully socialized economy, the government has to deal with private money and markets. It seems to me that MMTers are far too cavalier in their attitude to markets and blithely dismiss them as an insignificant irritant. Good luck is all I can say.

Neil Wilson,

“…so all there can ever be is a portfolio reconfiguration from term bonds with interest to permanent bonds without interest.”

And then the holders of “permanent bonds without interest” exchange them with “permanent bonds without interest” of another denomination. And the price of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination falls relative to price of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the second denomination.

“And then the holders of “permanent bonds without interest” exchange them with “permanent bonds without interest” of another denomination. And the price of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination falls relative to price of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the second denomination.”

And then the issuers of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination begin to shit themselves because they are concerned that the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination might lose value in terms of goods and services. So the issuers of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination have to choose whether they let the value of the “permanent bonds without interest” of the first denomination fall or drive up the yield on “bonds with interest”. The classic balance of payments constraint/trade off.

“The classic balance of payments constraint/trade off.”

Well, not exactly. The classic BOP’s constraint deals with the trade account, not the capital account. Close enough.

Henry Rech: Since your questions were intelligent and sensibly put, it took me a while to realize, in answering the last one, that it seems you have less exposure to MMT than I at first thought. Worrying about foreign currency is a bit like trying to run before you walk if you haven’t read up on the basics. If you do, I think you will find that some long held and widespread beliefs (or “facts” or “theorems” or “history”) are incoherent, illogical fables, and refutable by historical counterexamples.

Let’s say bondholders as a class have decided to quit the local currency … So they sell their bonds to the government.

But what are they going to get from the government, if it pays them? Local currency. So as has been explained, they are getting exchanging one bond (interest paying) for another (non-interest paying). As FDR said, “government credit and government currency are one and the same thing”. Modern Mainstream economics forgets this and makes nonsensical distinctions between them.

Secondly, the bond holders take their money and run for the exit

For the bondholders as a class, there is NO EXIT. All that an individual bondholder can do is exchange his bond with somebody for (a) government-issued money – just changing the kind of bond he holds or (b) something else – then the other somebody now holds the bond. The bondholders as a class cannot exit except by interacting with the government.

The only real exit is getting something non-financial from the government. Not currency. While government do sell a lot, the only thing “for sale” in quantities comparable to the National Debt is tax payments. Think of a tax as a fee, a sale of the right to perform the taxed activity. The main problem in most capitalist countries, most of the time is insufficient activity, insufficient demand, high unemployment. This means taxes are too high, soaking up too much demand, being too far from the barrier of inflation. So there is plenty of room for the bondholders to spend freely in order that they can get taxed, the only as-a-class exit logically possible.

And the government cannot set interest rates on its own.

Quite false. Something that must be unlearnt. Governments can control interest rates, as much as they do over saying a Lincoln is worth 5 Washingtons or 4 or 6 if they want. Currency is a bond. This control was once universally understood and practiced– and now forgotten outside of MMT. In many countries (the UK, Australia etc) it was called a “tap system” [the name due to William Beveridge, I believe. 🙂 Bonds were “on tap” for government-set prices (and hence yield) at any maturity, short or long. ]. Japan is a modern example of such conscious government interest rate control.

You are sometimes counterposing bonds vs cash, which is very wrong. What has some economic meaning is the total National Debt, calculated correctly – as the national debt (of course excluding nonsensical debt owed by the government to itself) plus the currency outstanding. The mainstream imagines that printing money (& low interest) is magically inflationary vs printing bonds (& high interest). Since there are genuine effects both ways, they often cancel each other. An exception is Latin American style chronic inflation. Following the mainstream, the tendency there is to use high interest to “fight inflation” – when clearly this high interest is feeding, not fighting, the inflation! Issue bonds at 100% / year interest rate and you are going to get about 100% / year inflation.

All that can happen is that the price of currency or bonds – government paper – vs foreign currencies or real goods and services go up or down. Currency depreciation or inflation. As others note above, this doesn’t seriously happen in a country with a working tax system, especially one that knows it has control over interest rates and keeps them out of crazy ranges (which makes the holders of existing bonds happy, not wanting to drive rates up and their own bond prices down, by selling them at fire sale prices). The tax system keeps the domestic value, domestic inflation under control and the value of exports puts a floor under the currency’s value in foreign currency terms. No spiraling downward.

Not as well organized as I should make it, but want to post this farrago now, fwiw.

Henry, one of the things the financial crisis showed is that the central bank can set the interest rate on new debt all by itself- it doesn’t take two to tango in this situation. Actually, MMT has shown that if the central bank does not interfere in the market the inter bank rate will fall to close to zero even in normal times and if the central bank wants to it can set the rates below zero. Look at the rates the Japanese government has been paying on its debt for the last 5 years.

The bottom line is the government does not need to borrow the money it creates. Not from wealthy bond holders and not from the general public. There are no bond vigilantes in a country with its own free floating currency.

But say you are worried about the exchange rate value of the currency. Since there is no intrinsic value in a fiat currency, this is a legitimate concern if you need products produced in another country. Foreigners who are not able to be taxed by the issuing government and who do not desire to buy anything produced in that country really have no use for your currency and its value should be zero to them. And it would be zero if the country produced nothing at all for export. But it does have some value because others do have a use for it so it can be traded on an exchange. But what underlies that value is that people need it to buy goods produced in that country, or to pay taxes to that country. So if you want to buttress the value of the currency, you must produce those goods that are in demand and the government must be willing and able to tax effectively.

Some Guy

Thanks for taking the time to try and knock some MMT sense into me. I\’m afraid it hasn\’t worked. You are correct, I am not well read and studied on MMT (something I will remedy at some stage). I have only read BIll\’s blog and others for the last 3 years. However, I do have over 40 years experience following the financial markets, a good deal of that time, professionally. From what I have seen in the last few days in comments, MMT does not gel with reality. As much as this notion sticks in the MMT craw, markets have to be reckoned with unless you are running a fully totalitarian socialized system.

I believe you are incorrect when you say there is no exit. There is an exit and it can impact on the value of the local currency which leaves the government with a dilemma. And having unlimited power to issue the local currency and tax does not relieve them of that dilemma. And you cannot expect government action to be perfect. It will more than likely undershoot or overshoot. There are lags which intervene which make policy making problematic. There are political constraints which add inertia. This is the real world. As far as I can, see MMTers reside in a perfect world of ethereal and nebulous thought.

I am not saying anymore as we are now all going around in circles, covering old ground repeatedly, and no doubt the axeman (as opposed to the taxman) is hovering in the wings. 🙂

“Since bond holders can not just take the money they loaned to the government for a certain time period and run”

Generally they can. There is usually an offer of last resort in the system that requires the government sector to convert the bonds to currency. For example the UK Gilt marker has a HM Treasury backstop for the GEMMs to allow them to maintain a market. So you can always get cash for your gilts.

Neil, I was not aware of that, is it in the bond contract? Or is it just something the Treasury does to ensure a market for previously issued bonds? Either way it really shows the lie that issuing bonds makes government spending less inflationary than when the government just creates the money for the spending, doesn’t it? That is the supposed reason for issuing debt in the first place- supposedly the bond takes that amount of spending away from the private sector for the duration of the bond. What a hypocritical joke it is to allow the bond to be cashed in ahead of time.

Jerry Brown,

“…one of the things the financial crisis showed is that the central bank can set the interest rate on new debt all by itself…”

I don’t think this is a valid conclusion at all. The markets were shell shocked and tentative for a very long time. Expectations were destroyed. This is the other side of the equation which you ignore.

“So if you want to buttress the value of the currency, you must produce those goods that are in demand and the government must be willing and able to tax effectively.”

This is not like turning on a tap at will. Industries cannot be materialized at will. And if your currency is on the nose, exporters to your country may think twice about it.

Henry Rech, I am not trying to antagonize you and am sorry if I have managed to do so. This is what I am thinking- it is sort of obvious that the government of, say, the USA can create money if it really needs to. It has done so in the past very directly under Abraham Lincoln during our Civil War and it does so in the present less directly through the Federal Reserve System which it created to do that along with some other important things. So given the ability to create money out of nothing when it wants to, it doesn’t seem too radical to me that the government can manage to ‘borrow’ that same money at an interest rate it determines itself if it wants to.

But the ability to create money or borrow it at whatever rate you choose does not mean that the money will have any value to anyone. That is where markets play a role. Maybe a US Dollar can be thought of as a claim of sorts on a small share of the US production of goods and services. Since the US still is a very productive country, the dollar still has some value in the market. But if it gets diluted by too much creation or faux borrowing without increased production of goods and services then the market is probably going to value it less. Taxation is one way to counteract that dilution. Increased production is another way.

And I completely agree that industries cannot be materialized at will. That is one of my biggest problems with economists who insist that free trade is always the best route to prosperity. Industries are not something you can just turn back on when they are gone. MMT had been in accordance with the free trader economists, but seems to be taking a more nuanced look at that issue lately.

Jerry,

No antagonism here at all.

Sure the government can create all the money it wants. All I am saying is that there may come a time when the markets say this has gone too far and the government will have reached a limit where it loses control and is stricken with dilemmas and difficult and contradictory choices. MMT appears to not recognize these at all.

Bill Mitchell is always careful to point out that real resources are always the limit on policy. Sure, a currency issuing government can purchase whatever is for sale in its currency- it doesn’t face a financial constraint like you or I do- but that doesn’t mean that everything happens to be for sale in that currency and it certainly doesn’t mean that real supply issues don’t exist. And it doesn’t mean that government spending won’t distort the market for that good. I actually think MMT does a better job than most other economic schools in pointing out the differences between financial constraints and real resource constraints.

Dear Henry Rech (at 2018/04/02 at 9:21 am)

As you say, you and others are going around in circles and there is little point in that.

May I add, that there is never a time that the ‘markets’ (you invoke this amorphous terror) can stop the government spending its own currency on whatever is for sale in that currency. Which includes idle labour. That means the markets can never prevent an economy reaching full employment.

Further, there are no infinite opportunities for the ‘markets’ to drive an exchange rate to some infinite depreciation. And as the Icelandic experience has recently demonstrated there is no way ‘markets’ can swap local currency financial assets for foreign currency assets if the sovereign government decides to prevent such transactions. Such prevention is not remotely like ‘totalitarianism’. Rather it is just sensible exercise of sovereign power in the interests of all residents when the interests of capital diverges from those interests.

So to say that “there may come a time when the markets say this has gone too far” is a rather meaningless statement and typical of the vague scaremongering that characterises the interests of the financial markets who seek to assert their importance and power.

Ultimately, a sovereign government can always play these interests out of the game, within a robust democratic polity.

We will not continue that debate though.

best wishes

bill

“…. the vague scaremongering that characterises the interests of the financial markets who seek to assert their importance and power.”

While I have failed to convince anybody of my arguments and you and others have failed to convince me of your arguments, I have made these arguments not as an apologist for “the markets” but as a realist. Unfortunately, markets do have too much power and I believe those that seek to “play these interests out of the game” will not be served by complacent disregard of their power.

The circumstances around Iceland’s default were unusual. There was fraudulent and criminal activity involved and deep systemic dislocation. This was not your normal balance of payments crisis.

That brings up the question of the nature of theory, and what makes a good theory.

There’s a great chapter in _The Feynman Lectures on Physics_, Book 1, Chapter 22, called “Algebra”. It’s a quick introduction to the development of Number Theory, and Feynman’s version of how mathematicians work. He describes steps of (maybe not his words) extension, inversion, completion. For example, addition is invented as an extension of counting. Then they faced the question “Now that I’ve added, how do I un-add?”, and work out the details of subtraction. Then “How can I subtract anything from anything?” and invent negative numbers and fit them into their supply of numbers.

The next level extends addition into multiplication, division and rational numbers.

The next creates powers, logarithms, and irrationals. Then it’s the continuum and you have to close Chapter 22 and move to David Foster Wallace’s Everything and More.

I say all that because I’m not really happy with a theory that writes off events I can point to as exceptions. That says “Iceland default? That’s a mystery. Unknowable. Theoretically impossible. You might as well try to subtract five from two.”

It’s possibly hubris for me to talk like this; I’m not a professional, but I want to know more than that. So I’m headed off this way. Bon voyage.

Dear Henry Rech (at 2018/04/02 at 10:26 pm)

You wrote:

There was a major financial collapse of the Icelandic-owned banks due to fraud etc as you say. But what followed was only “unusual” inasmuch as it was a case, in this neoliberal period, of a national government (via the President) asserting the democratic rights of the legislature against private foreign capital interests.

What they did was far from unique though.

In 2008, the Icelandic government introduced capital controls which prevented speculative trading in the króna and froze funds within that currency.

The controls stopped the hedge funds who had bought the assets of the failed banks from removing them from Iceland or coming back in and then being exchange back into other currencies.

Please read – Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=33707

Large hedge funds had their investments trapped within its sovereign borders. These were not ‘collapsed’ banks or anything. Just global capital seeking returns wherever they could.

The government used its sovereign powers and succeeded.

The ‘markets’ were powerless against the legislative power of the government.

And Iceland is now booming again. The central bank is now managing an appreciation rather than the opposite.

Also think about Malaysia during the Asian crisis in 1997.

Think about Argentina in 2001-02 – defaulted on foreign-debt, stimulated domestic economy and by 2005 the central bank was trying to stop the currency from appreciating to quickly such was the renewed inflow of investment funds trying to leverage off the growth.

One foreign hedge fund manager said of Iceland last year:

“There are a bunch of people I know who would love to put money into Iceland but they simply can’t because of restrictions on the inflows”

None of these were ‘special’ cases. They all demonstrated the legislative capacity of the national governments to take actions in the interests of their people rather than the foreign capital interests.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

I don’t deny that governments can have the power to take the actions they want to/need to. The question is, when should they and how should they?

Iceland’s situation was not a normal, run of the mill BOPs crisis. Its financial system was sick and rotten to the core in the context of a world financial system in deep crisis. I would bet that “the markets” at large would have accepted even welcomed the extreme and drastic actions taken by Iceland. Heck, even that neoliberal of neoliberal organizations, the IMF, lent them money to get through.

In extremis, when governments act contrary to the interests of private money, lethal consequences can result. Take Chile in the early 1970s as an example. If this does not speak to the power of money then nothing can or does.

Henry, the question of when a government should implement capital controls is not under the remit of MMT. As Bill is often at pains to point out, MMT describes the how. Politics handles the when.

Henry, you seem to be conflating what can happen when governments do act with when they don’t. Of course, when governments allow financial interests to exert too much influence on what goes on, you can get asset bubbles among other things, which according to Kindleberger and Bill Black always involve widespread fraud, indeed, Black contends that such bubbles quite often involve what he calls accounting control fraud where the CEO and others defraud the company for their own benefit.

I would like to recommend writers before the time of MMT whose views are consistent with this paradigm: Stuart Chase, Where’s the Money Coming From?, 1943 and Beardsley Ruml, “Taxes for Revenue Are Obsolete”, 1946. Ruml was chairman of the NY Fed. Chase’s book is available from Amazon. For a detailed technical discussion of the banking system, there is Eric Tymoigne’s various articles and his draft book on his university web site (one article being “Modern Money Theory and Interrelations between the Treasury and the Central Bank: The Case of the United States”, March 2014.) There is also Stephanie Kelton, “What Happens When the Government Tightens Its Belt?, New Economic Perspectives blog, 2014.

I am not sure whether these will be quite what you are looking for, but maybe they will help? They support Bill’s stance one way or another. I would like to mention one issue that seems to underlie what you have written. There are two principles involved in the writings I have mentioned and in Bill’s blog posts that should be distinguished.

One is the logical structure of the principles and what follows from them. The other is the support of the fundamental assumptions by the empirical data. However, as many, such as Paul Feyerabend, have argued over many years, the data do not speak for themselves; they need to be interpreted in terms of some theoretical principles, such as MMT. It seems to me that you appear to have been interpreting the data with which you have a good deal of experience by means of a framework other than MMT.

Neoclassical economic theory, which is a subset of neoliberal socio-political theory, is an alternative theory that just happens to be empirically falsifiable and, indeed, falsified by the data. I am not claiming that you are utilizing this theoretical perspective, but it is the mainstream alternative to MMT and the one that has been dominant for the past 30 or so years. Another alternative is the set of Post-Keynesian theories, which are held by some Deficit Doves — Bill is a Deficit Owl. Post-Keynesian theories are, by and large, inconsistent with MMT.

This isn’t as clear as I would have liked to have made it.

Mel, I am familiar with Feynman’s book, and other writings of his, and what he is doing in the passage you mention. Nothing MMT says is inconsistent with what Feynman is trying to get across. Let me use infinite sets as an example, something with which Feynman would have been familiar. He would quite rightly have said that, empirically, there is no such thing as an infinite set. However, it exists conceptually, and he would, of course, have agreed with this. This is what is needed to deal with the government’s ability to spend without having to borrow its funds from somewhere else. (I am going to ignore set cardinality — the actual size of the set, which is technically irrelevant in this context.)

Now, if we assert that the government can spend, in principle, without limit, it is reasonable to ask where the money is coming from and how big the pot is. Where does it come from? The government creates it ab initio, like any socio-culturally based conceptual construct, though based on a deep understanding of how a fiat monetary system works. (Commodity based monetary systems do not work in this way.) The government creates its own money out of thin air, as it were. Bernanke recently told a congressional committee exactly this when asked.

Now we know from whence it comes, the question becomes how much of it there is. We must note that we are talking about what is available in principle, not in practice. What is available in practice is influenced by political, social, and other considerations. If a government can create what currency it needs when it needs it, surely it can create as much as it wishes to or needs to. Since there is nothing to stop it, a government operating with a fiat currency system can in principle create a potentially infinite amount of money.

Of course, in the real world, it neither would nor could. This is no different from Newton stating that an object in motion will travel in a straight line unless deflected by an opposing force. We know from General Relativity that objects never generally travel in straight lines over substantial distances, as there are forces acting on them to prevent them doing so.

There are logical as well as empirical issues involved in macroeconomics, just as there are in physics. To take physics as an example, is Newton’s ‘law’, ‘F = ma’, an axiom, that is, a statement that is unjustified within the context it which it is introduced and, therefore, not derived from any other statement with in the given context, or is it an empirical statement induced from empirical regularities, or is it a definition? It is generally agreed that it is not an empirically derived statement. That leaves whether the ‘law’ is an axiom or a definition.

What hangs on this difference? If the statement is a definition, under the standard theory of definition, it is neither true nor false, but merely a clarification of how terms are to be used and what they mean. If the statement is an axiom, on the other hand, it has empirical consequences. This distinction is context-relevant because a statement can function as an axiom in one context and as a definition in another.

I won’t take this any further here.

Larry,

“It seems to me that you appear to have been interpreting the data with which you have a good deal of experience by means of a framework other than MMT. ”

Not really. (And BTW, I think neoclassical macro-theory as applied to the real world is essentially bullshit.)

I am firstly trying to understand MMT.

Secondly, I see historical evidence that supports the notion that markets could throw a spanner in the MMT works or at least should have MMTers think twice about what outcomes that MMT policy might result in. I don’t want to be dogmatic about this, but it seems to me that MMTers are too blase about a government’s ability to force markets into a corner. I suspect it’s the other way round. I am merely suggesting that MMTers should perhaps consider more thoroughly the actions/reactions of markets. The most basic issue for markets is to not see the currency debased. From what I can see, if MMT policy is adhered to this shouldn’t be a problem. But the real world world can be a tad problematic with economic lags and political constraints intervening.

My point from Feynman is that mathematicians take their theories seriously, and insist on extending and completing them. To say of some phenomenon “That’s not normal. We don’t look at that.” is anathema to such people. David Foster Wallace tells the story of Herculean labours to close up a gaping hole in theory. Immediately, I was thinking about waving away the Iceland default. On a larger scale, neoclassicals insisting that equilibrium theories are the only proper theories.

Henry, no serious MMTer would disagree with your contention that there are lags and that political constraints get in the way. The political constraints are outside MMT’s remit. While such constraints affect the economic system, any political constraints are not part of a theory of the monetary system, which is what MMT is primarily concerned with.

Your experience with markets I think has to do with the fact that neoliberal governments have allowed the markets to influence them, not because they can’t prevent this. FDR did not allow this sort of thing. No one wants to see the currency debased. But sovereign governments with a sovereign currency system can prevent this from happening if they have the will to do so, and that includes the political opponents within any democratic government.

Mel, neoclassical economists are really only concerned with the consistency and cleverness of their mathematical structures. In order to make them appear to explain real events, they make completely unrealistic assumptions, which a decent physicist would not do. Abstraction in modern physics is not like that found in neoclassical economics. For example, Boyle’s Law makes unrealistic assumptions, but the lack of reality in this case is not absurd and can be construed as a special case. It is not justified to do this with the rational actor or efficient market hypotheses or the ergodic axiom, which states generally that the future will be like the past.

To make assumptions like the ergodic axiom is to completely ignore, if not outright reject, both Knight’s and Keynes’ work on what I call ontological uncertainty (as opposed to epistemological uncertainty, where additional information can reduce the degree of uncertainty). In the former, no risk assessments are possible, while, in the latter, they are.

The only plausible justification for this kind of thing I think is to make their math equations tractable. In concentrating on making their equations tractable, they sacrifice empirical relevance. Samuelson did this deliberately in order to avoid any political critiques of his work.

Henry,

you said: “Unfortunately, markets do have too much power”

Indeed .. behaving like “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity”. (Rolling Stones Magazine), – if you will allow me to extend the metaphor from an individual private, profit- seeking bank to profit driven financial markets.

You mentioned totalitarianism in an earlier post.

Notice how self-interested Libertarian/neoliberal free markets end up having the characteristics of totalitarianism….