I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Monetary policy was not to blame

In the past, when I have advocated setting the central bank policy rate to zero and leaving it there several readers have suggested that this would set off uncontrollable asset price bubbles particularly in the housing sector. Indeed, the view among mainstream economists is that lax monetary policy in the US caused the sub-prime housing crisis. It is an intuitively attractive view for those who do not really understand how the monetary system operates and the complex distributional impacts that varying interest rates have. Today’s blog considers a US Federal Reserve research paper that has just been released which rejects the notion that “loose” monetary policy was to blame. It is an interesting research exercise.

In the US Federal Reserve research paper which was released on December 22, 2009 and entitled – Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble, the authors are interested in the role that monetary policy played in driving the US housing price boom.

They note an obvious motivation that has been the basis of attacks by mainstream economists on government policy. So investment in residences in the US had averaged around 4.5 per cent of GDP between 1974 to 2002. From 2002, however, the share rose to 6.25 per cent of GDP which they say was “40 percent above the average level and the highest share in a half-century”.

The Federal Reserve Paper notes that the “strength in housing demand created … a large bubble – in house prices” amounting to an average annual increase between 2003 and 2005 of 12.5 per cent. The collapse began in 2006 and in not yet in reversal.

They then juxtapose that with the observation that “(m)onetary policy was accommodative following the 2001 recession. The target federal funds rate fell from 6.50 percent in December 2000 to 1.75 percent in December 2001 and to 1.00 percent in June 2003. The level of the nominal federal funds rate during this period reached lows that had not been seen since the 1950s”.

This naturally leads to the questions: Were these two developments closely related? What role did the setting of monetary policy play in housing market developments in this period?

The authors conclude that:

… monetary policy was well aligned with the goals of policymakers and was not the primary contributing factor to the extraordinary strength in housing markets.

Further, while this study is confined to the US, housing price booms occurred in many countries and were supported by varying degrees of laxity in lending policy by banks. The Federal Reserve paper notes this point and concludes that:

Many advanced foreign economies experienced some sort of boom and bust in house prices, with some countries, such as Spain and the United Kingdom, having even higher growth rates in property prices than in the United States. Moreover, many other central banks’ interest rates were lower than the rates implied by simple policy rules, although these gaps were for the most part smaller than they were for the United States. At the same time, several countries, such as Germany, Switzerland, and Japan, experienced little to no increase in house prices, or even saw declines, notwithstanding persistently low interest rates in some cases.

This is a point that the IMF also concurs with (see below).

Readers will immediately realise that this runs counter to the growing claim by mainstream economists that lax monetary policy caused the problem. Many of the same economists are also claiming tha the expanded fiscal deficits are worsening the problem that the monetary excesses generated. Their cure: higher interest rates and a move to fiscal surpluses.

My assessment of the mainstream recommendations: they are lunatics.

One of these characters is conservative economist John B. Taylor, who would have been Bernanke’s replacement as Federal Reserve Chairman had John McCain won the US presidency, has been carping for some time now that the housing bubble was all about loose monetary policy.

As the Economist recently put it, “By slashing interest rates (by more than the Taylor rule prescribed) the Fed encouraged a house-price boom …” With low money market rates, housing finance was very cheap and attractive – especially variable rate mortgages with the teasers that many lenders offered. Housing starts jumped to a 25 year high by the end of 2003 and remained high until the sharp decline began in early 2006.

Note: this paper subsequently became National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper w13682, but that august institution doesn’t like to share its work freely so you have to work around their anti-freedom policies.

Taylor also wrote a macroeconomics textbook that was around for a while in the 1980s and I concluded at the time that you would not be able to teach from it nor would students learn anything useful about the way the fiat monetary system operates from it.

Taylor followed up on his claim made in the above paper in a speech to the Bank of Canada in November 2008 entitled – The Financial Crisis and the Policy Responses: An Empirical Analysis of What Went Wrong.

The Federal Reserve paper also notes that other mainstream economists jumped on the same bandwagon. For example, on page 1, they quote from Northwestern economist Robert Gordon (another producer of a very orthodox macroeconomics textbook) who told a conference in Sao Paulo, Brazil in August that:

It is widely acknowledged that the Fed maintained short-term interest rates too low for too long in 2003-04, in the sense that any set of parameters on a Taylor Rule-type function responding to inflation and the output gap predicts substantially higher short-term interest rates during this period than actually occurred … thus indirectly the Fed’s interest rate policies contributed to the housing bubble.

In the October 2009 edition of the IMF World Economic Outlook we read in Chapter 3 (page 93) that:

There is some association between loose monetary policy and house price rises in the years leading up to the current crisis in some countries, but loose monetary policy was not the main, systematic cause of the boom and consequent bust.

Further on (page 115), after a comparison of monetary policy settings and housing price growth in many countries that “differences in monetary policy settings across countries do not correlate well with differences in house and stock price growth”, which would seem to support the Federal Reserve paper’s main conclusion.

But then you read the Summary of Chapter 3 and the IMF says that:

Central banks fulfilled their mandates – inflation in advanced economies stayed within a narrow range in the lead-up to the current crisis. But central banks accommodated the relaxation in financial conditions, raising the risk of a damaging bust. Credit, shares of investment in GDP, current account deficits, and asset prices typically rise ahead of asset price busts, providing useful leading indicators of asset price busts. By contrast, inflation and output do not typically display unusual behavior

The IMF is clearly having a “bet each way”. They realise the evidence is against the assertion that lower short-term interest rates cause asset price bubbles but their neo-liberal inclinations are steering them in the direction of implicating monetary policy in some way. If they could not implicate monetary policy then the policy debate would change significantly.

In the quote above, Robert Gordon referred to a “Taylor Rule-type function”. What is that? Much of the dispute that the Federal Reserve paper covers hinges on the application or not of that rule.

The most discussed “simple monetary policy rule” was developed by Taylor himself – the so-called Taylor rule. It is simply an equation that when solved each period might bear some relation to the evolution of short-term interest rates.

However, Taylor and others seek to extend its influence beyond some “fit” of the data to argue that it provides the best estimate of where real short-term interest rates (the policy rate set by the central bank) should be set.

So the Taylor rule says that the real short-term interest rate (the policy rate adjusted for inflation) should be set according to the following formula:

(nominal interest rate – inflation) = natural real interest rate + a*[inflation gap] + b*[real output gap]

The natural interest rate is just assumed and is claimed to be the neutral rate that would see steady inflation at the target and full employment. Please read my blog – The natural interest rate is zero – for more discussion on why everyone should be deeply distrustful of those who talk about natural or neutral rates of interest.

The inflation gap in the equation is the difference between the current inflation rate and the central bank’s target (the latter is currently 2 per cent in the case of the Federal Reserve).

Finally, the output gap is the percentage deviation of actual GDP from its potential level (which is claimed to be a full employment level). Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Fiscal rules going mad … – for more discussion on the traps in computing potential GDP and output gaps.

In his 1983 paper that introduced the rule, Taylor weighted the inflation and output deviations equally setting the parameters a, b at 0.5 (Reference: Taylor, J.B. (1993) ‘Discretion Versus Policy Rules in Practice’, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39: 195-214)

So the interpretation of the rule is that if inflation is above the target and the output gap is falling then the nominal interest rate should rise and vice versa.

What if the two “gaps” are not working together? For example, in a stagflationary situation inflation may be above the policy target but there is a large output gap. Then the rule would predict nominal interest rate changes according to the weights given to the parameters on the respective gaps (a and b). When they are set at 0.5 then the two gaps are given equal weighting.

No central bank admits to being guided by this rule. The US Federal Reserve certainly has never indicated it is influenced by it. However, Taylor claims that under Greenspan (the so-called period of “Great Moderation”) the rule tracked the changes in monetary policy reasonably closely. That point is contestable but tangential to this blog.

Athanasios Orphanides who is the Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus and who had previously worked within the US Federal Reserve system is very critical of the rule. This paper is somewhat accessible and outlines the issues. See also (Orphanides, A. (2003) ‘The Quest for Prosperity without Inflation’, Journal of Monetary Economics, 50: 633-663, which is harder for the layperson to grasp).

He points relate to the dangers of using the rule in a mechanical way when the key concepts (real natural interest rate and potential output are fairly flaky and notes that the interest rate outcome would be very sensitive to measurement error which could easily lead to counterproductive monetary policy outcomes.

There are also many other critiques of the rule both in conception and application which you can seek out yourselves if interested. I wouldn’t bother actually!

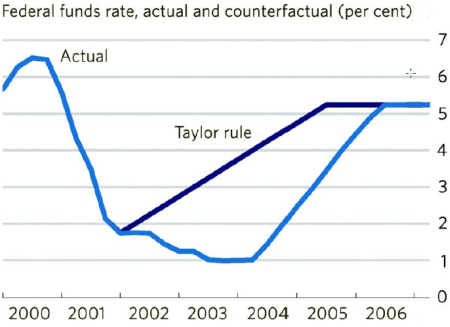

The following graph is the motivation behind the claims that loose monetary policy caused the housing crisis. It was published in the Economist in October 2007 and is reproduced from Taylor’s Bank of Canada paper noted above. Taylor uses the graph to conclude (in the Bank of Canada paper, pages 1-2) that:

It examines Federal Reserve policy decisions – in terms of the federal funds interest rate – from 2000 to 2006. The line that dips to 1 per cent in 2003 stays there into 2004 and then rises steadily until 2006 shows the actual interest rate decisions of the Federal Reserve. The other line shows what the interest rate would have been if the Fed had followed the type of policy that it had followed fairly regularly during the previous 20-year period of good economic performance. The Economist labels that line the Taylor rule … [and it] … shows what the interest rate would have been if the Fed had followed the kind of policy that had worked well during the historical experience of the “Great Moderation” that began in the early 1980s.

Now the Federal Reserve Paper note that they “do find that the federal funds rate was below levels suggested by some simple policy rules during this period” although they would not agree that the difference is as stark as that presented in the Economist graph above. Even Taylor qualifies that graph as you will note from his quotation.

However, the approach taken by the Federal Reserve paper to the question as to whether monetary policy was “loose” or “tight” is to define it against “some baseline for comparison”. For the period between 2003 and 2006, they conclude that:

… the federal funds rate was below levels suggested by some simple policy rules during this period. But a number of considerations suggest that the simple finding, taken on its own terms, may be less stark than some observers seem to believe.

The point they make is that it is important to take into account “the effect of real-time measurement … the choice of price index” and “the parameterization of the policy rule” – and under reasonable assumptions “the deviation of the policy rate actually adopted by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and that indicated by simple policy rules is not very great”.

In relation to the effect of “real-time measurement”, the authors note that:

… the benchmark against which effectiveness should be gauged is not what theoretically might have been attainable given perfect foresight of the future, but what could reasonably have been expected given what was known at the time the policy actions were taken.

In this respect they consider the settings were consistent with what the broader understanding of trends were in the economy – “Given the near attainment of both the price stability and the maximum sustainable employment objectives of the Federal Reserve, there appears to be little to suggest that the federal funds rate should have been markedly higher”.

So outside forecasters at the time broadly agreed with the monetary policy stance.

But having said all that, they conclude (page 21) that:

… the federal funds rate was a bit lower than suggested by the Taylor (1993) rule.

So did this matter?

In terms of timing, there is some dispute about when the US housing boom began. Some say it began in the late 1990s, but it is without doubt true that the escalation in housing investment coincided with the period where the federal funds rate was slightly below that suggested by the Taylor rule.

While this gives some credence to the mainstream critique of “loose” monetary policy, the authors note that in “real-time” (that is when things were happening) there was considerable doubt “about the sustainability of the increase in home values” (page 23).

The authors using simulations of the Federal Reserve’s FRB/US model to show that if the Taylor rule had have been followed at the time, GDP growth and unemployment would have been much higher earlier but that there would not have been much difference in the evolution of residential investment.

They perform other modelling (Vector Autoregressive regressions) and the conclusion they reach (page 29) is that the “the housing market developments over 2003 through 2008 were far outside the 2-standard deviation confidence bands based on observed macro variables, including the federal funds rate and the VAR’s estimated parameters”

What does that mean? It means that the rise in the share of residential investment in GDP in the US was outside what could reasonably be expected given all the information that was available at the time. They claim this suggests that “macroeconomic conditions did not drive the housing market developments in this period – at least not in a historically typical manner”.

As noted above the IMF studied whether there was a relationship between the degree of accommodation in monetary policy (that is, low interest rates) and the housing booms. If the loose monetary policy hypothesis was correct then we should expect to see a significant positive relationship between the degree of accommodation and housing prices.

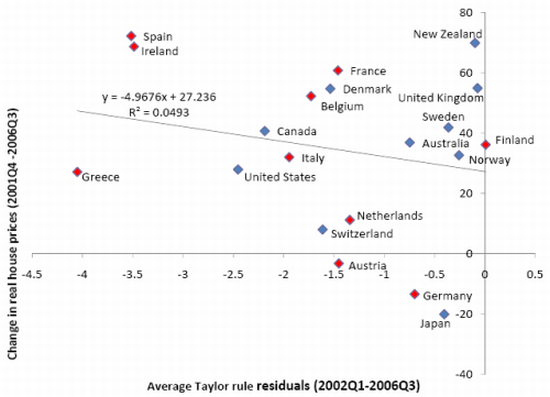

The research finds no significant consistent relationship between the two. The following graph (reproduced from Figure 12, page 32) shows the gap between the actual short-term interest rate and that predicted by the simple Taylor rule (as above) on the horizontal axis and the rise in real house prices from 2001:Q4 to 2006:Q3 on the vertical axis.

So a movement to the left along the horizontal axis would indicate that the actual monetary policy setting was further below the Taylor rule estimate and thus according the mainstream economists – increasingly “loose”. In a regression sense, there is no statistical significant relationship found between the two sets of data.

The Federal Reserve paper concludes:

Although some countries such as Ireland and Spain had policy rates that were low relative to the policy rule along with large increases in house prices, many other countries with big rises in house prices, including the United Kingdom and Australia, had small deviations from the policy rules.

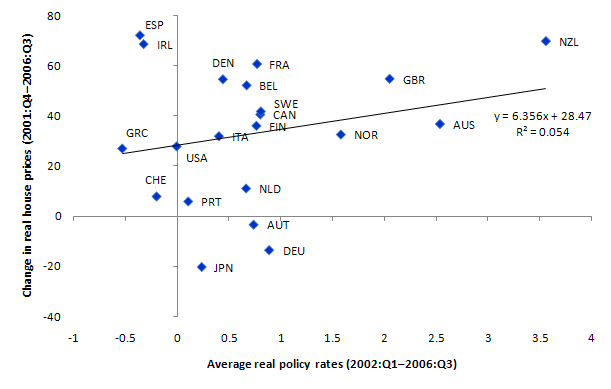

You can see an extended version of this analysis in the IMF WEO October 2009. The following graph is reproduced from their chart 3.13.

This shows the relationship between actual real policy rates and housing prices for the periods noted. The obvious conclusion is that there is no significant relationship during this period between actual monetary policy settings and housing prices. So this finding is beyond the hoopla of the Taylor rule which should be consigned to the historical wastebasket.

Conclusion

So what did cause these unusual “housing-specific developments … in this period”.

The Federal Reserve paper conclude that there is “little evidence that the setting of U.S. monetary policy could have directly accounted for a substantial share of the strength in U.S. housing markets between 2003 and 2006.”

But these unusual “housing-specific developments” were accompanied by changes in the :

… form of mortgage finance – the prevalence and nature of mortgages with adjustable rates versus fixed rates, the role of other “new” or exotic mortgage features, and the role of different types of lenders and securitization paths – all shifted during this period. These shifts undoubtedly fed on each other, with strong demand for housing and rising house prices spurring unsustainable evolution in the nature and perceived risks associated with mortgage innovations and vice versa.

They admit that while these innovations were drivers their research does not “explain why such developments occurred”.

And that takes us back to modern monetary theory and the related understandings.

Our work has documented the rising influence of neo-liberalism over this period. The impact on policy settings, particularly those relating to financial regulations, had a profound influence on the developments that the Federal Reserve authors are interested in.

For example, the relaxation of the 80-20 rule; the overturning of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 by Congress under intense lobbying pressure from the large Wall street bankers; and other moves to self-regulation set in place the dynamics for further events.

Without close scrutiny, the sub-prime boom then bust was, in part, clearly the result of mortgate brokers using fraudulent appraisals and fraudulent income statements to maximise their commissions, knowing that the assets were being chopped and bundled by the likes of Goldman and Citigroup and on-sold to unsuspecting investors who had no idea of the inherent risk in the securitised assets they were buying.

Further MMT tells us that monetary policy is the least effective of the aggregate policy tools available to government. So it is no surprise that a low interest rate did not set off chaos. This finding is also important because it should provides noe comfort for those who consider a zero short-term interest rate policy, which is implied by MMT, is likely to set off dangerous asset price bubbles.

In the period analysed by the research paper we have been discussing here – lower interest rates did not cause the housing price explosion.

That is enough for today!

The Taylor formula is a function of a “natural rate” input that’s as open to question as the Taylor formula itself. The formula is self referencing in that sense. It’s a function of a whimsical input. And it’s like a risk manager’s math formula (e.g. value at risk) that’s dangerous when relied on too heavily.

I agree that mortgage finance factors dominate low rates in the explanation of the bubble. But I also think that low rates were a lethal breeding ground for those finance methods in this cycle – particularly in accommodating ultra low teaser rates on adjustable rate mortgages. Those rates lit the fire under the fraud that took advantage of them.

Aaahh!

So I’ve been wrong all theses years?

Ah, well. I guess there’s something to be said for finally seeing the light.

Thanks, Bill. I think.

Interesting. Thank you…

Nicely done!

I think the best case that could be made for the opposing viewpoint is that tighter money in the leading market (the US) would have likely shortened the boom by a few months. But since the boom was about a decade in the making, that could hardly have been the decisive factor.

Gotta agree with JKH above that the lower policy rate extended the target area for the money-marketeers.

But this was not the cause, as lower rates elsewhere produced opposite results.

So, am I correct then to conclude that the major contributors to the fiasco were the –

“changes in the :

… form of mortgage finance – the prevalence and nature of mortgages with adjustable rates versus fixed rates, the role of other “new” or exotic mortgage features, and the role of different types of lenders and securitization paths – all shifted during this period. These shifts undoubtedly fed on each other, with strong demand for housing and rising house prices spurring unsustainable evolution in the nature and perceived risks associated with mortgage innovations and vice versa.”

Is that the shadow bankers?

I was on the ground in California at the time that this was unfolding. I can report that the principal cause of the problem was, surprise, red hot demand. Obviously, there was demand on the part of buyers looking to make a quick buck. Later, others rushed to get in before they were shut out by skyrocketing prices. The second type of demand was the demand for mortgages to securitize and sell into “the giant pool of money” that was looking for the most lucrative yield on AAA securities in which to park. Mortgage brokers were hungry for prospects, because they were making gobs of money doing deals to meet this demand. There wasn’t a whole lot of rational thinking about consequences by either debtors or creditors. It was shear passion unleashed on both sides. This was a marriage made in hell.

The temptations were too great, and fraud became rampant. Buyers fudged or lied on documents. Mortgage brokers check even in the most obvious cases. I know a women with three kids, no husband, no job, and with a recent bankruptcy that easily got a mortgage. The firms competing for mortgages to securitize didn’t really care about what they were getting as long as the requisite paperwork was there. The buyers of the securities were dazzled by Wall Street names and AAA ratings. A lot of things converged and fed on each other.

This was a gigantic crime scene that hasn’t been investigated. The problem is more a forensic one than an economic one, as Bill Black and others have been saying for some time.

Were low rates implicated? Yes, to the extent that deals had to be structured that would pass muster with respect to the monthly. Rates had to be low enough so that the deal could work for at least a year or two. But interest rates weren’t all that big an issue either. Toward the end, many exotic loans were interest only, and finally, just what the buyer could afford, even if it wasn’t all the interest.

Meantime, people already in and way ahead were taking out seconds to buy other properties. It was pretty wild. Very few people bought with the idea of holding. As far as they were concerned, they were renting a property for a year or two to flip. Monthlies were also low enough for flippers to be able to carry properties for the time it would take to turn the deal around, usually only a matter of months. I saw one scrub lot sell for $112,00, be “improved,” and sell six months later for $250, 000. The improvements (well, septic, minimal road) were less that $30,000. Enterprising flippers could have several deals going at once. Early in the game, some people quit their day jobs and made millions in a year or two flipping houses.

Unfortunately, toward the end, a lot of people renting saw that things were getting away from them and if they didn’t jump in quickly they feared they’d be shut out of the market forever. Since all you needed was a warm pulse to get a mortgage, a lot of people were suckered in this way and are now deeply underwater. I know some of them, too. It wasn’t all buckets of gold for everyone.

The game could have ended with higher rates raising monthlies beyond reach, but instead it was the skyrocketing prices. It just got too expensive to carry these deals, and when the music started to slow down, the savvy people unloaded as quickly as they could. Prices peaked, buyers disappeared, and the people who were still in were stuck. It was quite a ride, but it was over. And it wasn’t just property owners that got hit. Many builders got stuck with unfinished projects and lots they were paying on. I have a friend who picked up some lots for development but got stick with one. He had bought it at a tax auction for $17,000. He had it on the market at the peak for $90,000 and began dropping his price but not quickly enough. Now comparable lots are being offered for $5000, and taking a long time to sell.

No, it wasn’t just rates from where I was looking at it.

isn’t the point that low rates which translate into low monthlies merely act as a catalyst in an environment where the positive

exuberance is well set. As is the case now, with several months of rising prices on the back of ZIRP.

So i’m afraid i have to disagree with Bill on this one, where ‘Monetary policy was not to blame’ it was partly to blame. It clearly wasn’t THE problem, but would higher monthlies have been more or less likely to fan the flames of the fire that had already been lit ?

Prices skyrocketed to unprecedented YoY highs a year or two after the central bank in the UK reduced IR’s to ward off the threat

of recession at the tail end of 2001, as was the case in the US. Don’t they say IR changes take a while to work through the economy once they are set by the central bank ?, maybe this is what happened to create the superboom from 2002 onward. It’s undeniable there was demand and rising prices BEFORE then, it’s a question of what further distortions low IR’s created.

Are we seriously trying to suggest that low IR’s weren’t stimulatory. I’m not convinced, and it’s not as if the Fed doesn’t have an interest in saying loose monetary policy was not to blame. Same goes for any supporter of Zero interest rates, i mean for crying out load the Fed spent years denying the very existence of a bubble. And now in the period following the post-GFC revisionism their ‘save the world’ actions probably help them to believe they were right all along, There never was a problem, and monetary policy was never part of the problem.

give me a break.

“This finding is also important because it should provides noe comfort for those who consider a zero short-term interest rate policy, which is implied by MMT, is likely to set off dangerous asset price bubbles.”

Hi could you explain this please? It isn’t clear what you mean. Is a zero rate going to cause asset price bubbles, and who exactly is getting no comfort from these findings? Cheers.

As Tom Hickey says, it was the atrocious regulation and risk management that allowed the property boom and mortgage frauds to reach such high levels in some parts of the US. Zero interest rates allow some form of money illusion to help hide what is happening to the naive, but central bankers and risk managers and CEOs in banks and shadow banks were not supposed to be naive, and even outright fraudulent in some cases. Zero rates are like the tricks used by magicians to catch peoples’ attention and draw it away from where the real action is occurring. They’re so obvious that people watch them closely, assuming that this is what is causing something to happen.

If economists and regulators are worried about the effect of low interest rates on asset prices, it sounds like a job for the new systemic risk regulators that have been talked about for the last year or so. Let’s have them looking at where the credit is coming from that is supposedly flowing into the possibly bubbling asset classes and helping to stop that flow if necessary. Interest rates are far too blunt a tool to use for this.

Dear Vimothy

You might like to read the blogs Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks and The natural rate of interest is zero! – to see what I think about ZIRP etc.

The finding suggested that the lower than Taylor rule policies was not implicated in the asset price bubble. If that is true (which is consistent with modern monetary theory) then it provides no case for arguing against very low interest rates on the grounds they will be inflationary.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill.

But a great bulk of those upstream investors in the housing debacle found its origin in Asian investments seeking safe haven (from the prior panic of 1998). And that was tied back to our trade deficits that glutted their banks with huge deposits — making for banks awash in deposits, but without a strong middle-class consumer base to lend it to (they wouldn’t have had the same fat depositors demanding ridiculous returns had they not beggared their workforces into penury … same problem now ).

So their huge pool of money washed up on American (and Irish, Viking, and Spanish) shores, pressuring sovereign investment and depository banks to come up with magical ROI. Bank managers work with OPM (Other People’s Money, pron. ‘opium’) – the bigger the pile, the bigger the bonuses. Stupid, witless principle #1: Never ever turn big, huge, fat money *away* EVEN if it tips the fractional reserve ratio into excess cash, even if there’s no way to lend it fast enough, sanely, safely … we’ll just have come up with ways to lend it *dangerously.*

Maybe you can recall a similar depository bubble fed a debt bubble in New England in the mid-1980’s, with predictable results. Commentators at the time commented on how it bore the portents of damaging wealth accumulation within the USA – the specter of yet more debt bubbles going pop.

But lessons be damned, we had to go & gut Glass-Steagal, enabled all manner of shoddy debt securities (& the ADDA of 1993) and we were off to the races with a mushrooming household & real estate debt bubble, while we offshored base commodity manufacturing jobs at an accelerating rate.

It had all the classic signs of a trade deficit-fueled and investor-driven debt bubble. By 2007 more than 35 American municipalities were in recession due to jobs offshored to China (heard on NPR market rpt), all the while we were flipping houses & using them like ATMs. I’m so glad that Greenspan & the Bush admin had their hand firmly on the tiller, aren’t you?

Lo and behold, excessive wealth accumulation is now a worldwide problem, with megabets flying around without any connection to the ground beneath them. We cut taxes on our investment class so they could take amass private treasuries, pull ROI out of Asia as production globalized. Well, why not? We *knew* the Asians were going to rook their workforces & the price-point margins were far fatter, so smart money goes where?

So what if it decimated our own production? Wealth is wealth, whether its in more hands or fewer hands, as any monetarist will tell you. And with the dollar kept strong, reserve currency status kept intact, oil stays cheap, and we can slowly cram down wages (not mortgages mind, debt shouldn’t ever go away, even when you’re flat broke…). Oh, and the 1% holding 40% of the wealth can only buy so many Asian durables & commodities — that’s a benefit. Low commodity price inflation =’s low interest rates.

Devalue the dollar: Up-value our offshore ROI while devaluing our debt to China? New Mandarins no likey?

And if we boosted the downscale economy, wouldn’t that see a resurgence of velocity consumerism buying foreign goods, fueling even bigger trade deficits? Would that mean it’s national policy to beggar our own consumers and workforce, stopping us from buying any more offshored crap than we already do?

Is the upshot that policies are in place to protect Western investments in Asia for the time being, to rake the wider returns from Asia’s unfair (to both us & their own wage slave workers) price-point advantage? Is this a case of an idle & shiftless rentier class, coupled with our own zombie banks, indifferent to the working class?

And here we have the USA & the EC pressing each of our respective states into austerity so to protect currencies & investments, even though the medicine risks yet more pain. In so doing – the West protecting its currencies – doesn’t this favor Asia while exacting a toll on our workforces (yet more offshoring), thereby suppressing our own wages?

And yes, I know I’m being a bit rhetorical & painting with a broad brush; I’m no economist, but it seems to me the world has gone here before. Nouriel Roubini’s has suggested a 3-prong solution, sounds similar to what a great many reasonable people are suggesting — rebalance world wages & trade, unwind global debts (and do something about derivatives) & reinvest in infrastructure. What’s stopping us from headed *there* from *here*?

I suppose we’ll get there eventually, but not today, because do we first need to rake Asian productivity just some more, taking yet more creme off the top of offshored trickle-down?

Funny thing about domestic microcapital. It can fail too, but it doesn’t empty out the kiddy pool when it crashes.