I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Wall Street lobbying helped bring the economy unstuck

In yesterday’s blog, I discussed one of the more novel ways that the conservative lobby against government spending is mobilising to present their case. In that paper, it was argued that spending “funded” by taxation is always captive to political lobby groups who ensure the government will waste spending and undermine the productivity of the economy. Alternatively, the author claimed that government spending should be disciplined by financial markets who would reduce the waste that is inherent in public outlays. While there were several flaws in the argument the one that we deal with today focuses on the assumption that financial markets allocated resources optimally.

The paper said that projects “funded” by taxation “encourage individuals to lobby to be members of favored groups … Economies prosper, however, when governance institutions reward productive efforts, and suffer when individuals instead seek redistributive rents”.

So the answer proposed is to reduce spending and taxation overall (that is implied by the conservative agenda) and force whatever minimal spending is required to be “funded” by debt issuance because the financial markets “can give us a better idea of the appropriate scope of government activity and encourage a less wasteful employment of public resources once that scope is set”.

Note the “funded” is always in inverted comma when I report some mainstream mis-representation of the role of taxation. Modern monetary theory (MMT) leads to an understanding that taxes do not “fund” anything because the notion of “funding” is inapplicable to a sovereign government which issues its own currency. Such a government never needs to fund its spending.

This is true despite the institutional arrangements and supporting rhetoric that makes it look as though a sovereign government collects tax revenue, pops it into a bank and then subsequently spends it. The role of taxation is to reduce the private sector purchasing capacity to either give more real space to the public to conduct its socio-economic program without inducing inflation.

Anyway, apart from fundamentally misunderstanding the way the fiat currency system operates and confusing the roles of taxation and debt-issuance, the writer seems naive in the extreme about the relative lobbying behaviour of taxpayer groups and financial market interests. The implication is that the latter is an impersonal, market-driven approach where competition and arbitrage create optimal cost-minimised outcomes and the former is a viper’s nest of pork-barrelling and special interests.

The naivety of this position is highlighted by an IMF working paper that was released late in 2009. The paper – A Fistful of Dollars: Lobbying and the Financial Crisis – written by Deniz Igan, Prachi Mishra, and Thierry Tressel. The paper is somewhat technical with lots of regression analysis but is generally accessible.

The authors claim it is “the first study to examine empirically the relationship between lobbying by financial institutions and mortgage lending in the run-up to the financial crisis”, which is probably correct.

They “identify lobbying activities on issues specifically related to rules and regulations of consumer protection in mortgage lending, underwriting standards, and securities laws”.

There were two types of legislation that were targetted. Money was spent to derail legislation that was promoting tighter restrictions on the financial markets. For example, “tight restrictions for lenders focus primarily on predatory lending practices and high-cost mortgages … many bills contain restrictions/limits on annual percentage rates for mortgages, negative amortization, pre-payment penalties, balloon payments, late fees, and/or the financing of mortgage points and fees. Expanded consumer disclosure requirements regarding high-cost mortgages (such as including the total cost of lender fees on loan settlement paperwork or disclosing to consumers that they are borrowing at a higher interest rate) are introduced in some of the bills.”

Some of the bills would have forced the banks to make more complete assessments of the consumers’ ability to repay the loans and that loans should not be in excess of 50 per cent of the reported income.

The study focuses on 33 federal bills in the US that would have reduced predatory lending and introduced more responsible banking. The Appendix provides many examples of this type of legislation that was targetted by the lobbyists. For example, the Predatory Lending Consumer Protection Act 2001; the Predatory Mortgage Lending Practices Reduction Act 2003; Responsible Lending Act 2005; Predatory Lending Consumer Protection Act of 2002 and others were never passed by the US House or Senate after the lobbying efforts.

They show that the lobbying efforts in this area of legislation was overwhelmingly successful.

Money was also spent to promote legislation that reduced restrictions on financial markets including “lower down-payment requirements; state and local grant funding to provide down-payment assistance for certain borrowers; hybrid adjustable rate mortgage programs; revised mortgage insurance premiums and cancellation policies; and financial assistance when purchasing homes in high-crime areas or low-income areas.”

There were also bills that relaced the the oversight on the large mortgage providers such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These large providers would originate the mortgages which would then be bought and packaged by the big investment banks and on-sold to other investors. You see bills like “American Dream Downpayment Act” passed which was the target of lobbying and made it easier for low-income families to gain a mortgage.

Again, the lobbying efforts in this area of legislation was very successful.

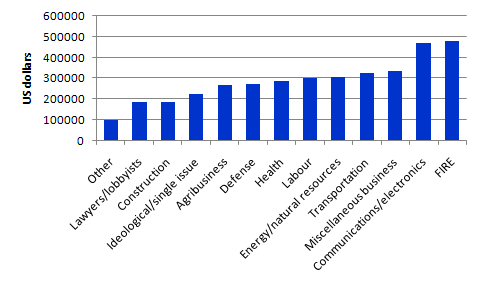

The following graph is reproduced from their Figure 1 which shows the “lobbying intensity (defined as lobbying expenditures per firm) by sector” in US dollars in 2006.

It is clear that firms in the FIRE industry (Financial, Insurance and Real Estate) spend more on lobbying that firms in other industries. “Firms lobbying in the FIRE industry spent approximately $479,500 per firm in 2006 compared to $300,273 per firm in defense or $200,187 per firm in construction”. The paper also shows that the “the lobbying intensity for FIRE increased at a much faster pace relative to the average lobbying intensity over 1999-2006.”

On page 65 (Table A2) you can see an actual copy of the Lobbying Report Filed by Bear Stearns where they paid $US500,000 to buy votes that would water down the The Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act of 2007 in the area of “lending and securitization standards”.

On Page 67, you see that Bank of America paid $US1,020,000 to derail a number of financial market bills.

So what did they find?

It turns out that the US banks that spent the most on lobbying the US government to ease financial market regulation in their favour:

… (i) originate mortgages with higher loan-to-income ratios, (ii) securitize a faster growing proportion of loans originated; and (iii) have faster growing mortgage loan portfolios. Our analysis of ex-post performance comprises two pieces of evidence: (i) faster relative growth of mortgage loans by lobbying lenders is associated with higher ex-post default rates at the MSA level in 2008; and (ii) lobbying lenders experienced negative abnormal stock returns during the main events of the financial crisis in 2007 and 2008.

That is, the firms who lobbied the most were mostly likely to be the firms that created the crisis.

After considering a number of possible explanations for the finding that “lobbying is associated ex-ante with more risk-taking and ex-post with worse performance” they conclude that the evidence is consistent with the view that:

… lending behavior is to some extent affected by politics of special interest groups. They provide suggestive evidence that the political influence of the financial industry might have the potential to have an impact on financial stability.

The conclusion supports the claim that major financial institutions were successful in undermining regulation that would have made it harder for them to engage in the more risky and predatory antics.

It also is clear that the Wall Street lobbyists funded votes that made it easier for them to escalate the housing boom in the US driven by the sub-prime market.

It is clear that from any perspective this lobbying led to a “misallocation of resources” which means that financial markets are not good judges of the best use of a society’s resources nor provide effective discipline to ensure the socially optimal configuration of private (and public) spending is achieved.

Anytime you hear some economist say that private markets allocate resources better than the government you should just laugh. There is overwhelming evidence that the proposition is simply untrue. All allocations require regulatory forebearance and transparency in decision making.

In the case of financial markets we could reduce these unproductive activities by outlawing most of the activities in that sector and only allowing those aspects that advance public purpose (that is, increase real welfare standards) and maintain financial stability. The clock has to start ticking on this industry. There should be as large a mobilisation by citizens against the influence of this industry as there is about climate change. Both issues are central to our future.

The UK Guardian carried a column about the IMF report (January 4, 2009) and quoted a fraud investigator who helped uncover the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) scandal in the 1990s. He said:

In my entire career investigating financial fraud, fraud was always explained away as perpetrated by a few bad apples. This is plainly untrue. There has been a systematic refusal to look hard at how this has happened. I’m delighted the IMF are using mathematical formula to look at something that has been obvious to so many for so long. There’s nothing new and surprisinmg about this. The question is where was the IMF when this happened?

When you evaluate what sort of regulations have been introduced to date – some 24 months into the crisis – you will have to search hard for tighter mortgage controls of the sort that were contained in the US government bills that were successfully derailed by the Wall Street lobbying efforts.

There is also clear evidence that US banks pocketted billions in federal government bailouts (under the TARP) yet continued to heavily lobby legislators who were considering increasing financial market regulation (Source)

Further, in Australia even the central bank gets involved with shady political lobbyists. On August 4, 2009 there was a report in the Melbourne Age entitled – Cash for contract claims which said that:

A Reserve Bank of Australia subsidiary allegedly paid a six-figure sum to an Indian political lobbyist as part of a campaign to break into the world’s biggest banknote market.

A complainant with intimate knowledge of the operations of polymer banknote maker Securency has told Australian Federal Police that a senior company executive allegedly disclosed to him in 2007 that a $120,000 donation was made to Indian political figures.

This was not the first allegation made against this company which is half-owned by the Reserve Bank. It seems that they have been bribing foreign officials in a number of countries to to win banknote supply contracts.

The same authors reported in November that:

Securency’s senior managers shredded documents and hid files to stop RBA auditors learning the full details of its arrangements with foreign middlemen.

The RBA wanted to examine Securency’s agent arrangements in 2006-07, but well-placed sources claim Securency’s management stymied RBA auditors to the extent they could not conduct a proper examination.

The company was allowed to continue using its vast network of foreign middlemen and it continued to send millions of dollars into offshore tax haven accounts.

You might wonder what this is all about. Well the RBA developed and introduced the first polymer banknote 22 years ago which was a world first in high technology currency development.

The motivation came in the late 1960s when there was a major counterfeit $10 bill scandal just after the new decimal currency was issued. As an aside, I went to school with a person related to one of the counterfeiters.

Securency was formed as a 50-50 joint venture in 1996 between the RBA and Innovia Films, which had had produced the polymer material. The original joint venture was between the RBA and Belgian polymer manufacture UCB who later sold its interest to Innovia.

At the time, public-private partnerships were becoming the flavour of the decade. The neo-liberal distaste for public sector activities forced a number of enterprises to be privatised and/or forced into PPPs. The RBA should never have got involved with a private firm in this context.

It could have simply purchased the polymer and exploited the opportunities itself. But the rhetoric was always that the “market” knows best and public companies are inefficient and wasteful.

The recent financial crisis has certainly knocked a few of those claims “out of the ground”. (cricket term).

Propaganda machine steps up a notch

Just before Xmas there was a press release announcing that:

The Fiscal Times, a new independent digital news publication devoted to quality reporting on vital fiscal, budgetary, health care and international economic issues will launch in early 2010 … The news operation will begin publishing with a roster of experienced journalists and leading opinion contributors, whose reporting and insights will aim to drive the conversation surrounding our nation’s most pressing economic issues.

Further, the Washington Post which in its glory days undid the corrupt US President Nixon has entered a partnership with the Fiscal Times to “jointly produce content focusing on budget and fiscal issues that will be available to both publications.”

The Fiscal Times is being funded by Peter G. Peterson, the right-wing Wall Street billionaire who pumps out material and buys exposure for his ravings about the fiscal crisis and the impending disaster as the US Social Security system goes broke.

The first joint venture article – a propaganda piece against US social security spending was published in the Washington Post on December 31, 2009. Shameful.

Cartoon source: The cartoon was drawn by David Horsey and was published on Thursday, October 29, 2009.

The role of taxation is to reduce the private sector purchasing capacity to either give more real space to the public to conduct its socio-economic program without inducing inflation.

Perfect example of the academic gobbledygook I’m talking about. What we have here is nothing more than a $5 phrase for taking one group’s money (and, by implication, freedom) for purposes of funding another (supposedly much smarter) group’s objectives.

Further, out of this inability to properly define taxation grows the crazy notion that government can somehow make an end run around real expenditures and obligations (spending and debt) by creating money (in the short run) and wealth (in the long run) out of thin air.

The only situation in which this scenario could be remotely plausible is if the scarcity problem were already solved for ALL participants in an economy (i.e.; resources were unlimited and therefore “free”). Only in this case does distribution surmount production as the prime problem within an economy, allowing this redistributionist strategy to function without wrecking money as both a store of value and transactional tool. IOW, there is no free lunch.

I am unclear on how the following works: Pimco’s Bill Gross recently said the following to Time, “They’re [the Fed} are buying a trillion dollars of them [MBS], or have over the past 9-12 months, and so we sold them a lot of ours. Now, what did we do with the money? We bought Treasuries, we bought corporate bonds, and so the bond markets in general have benefited, as have stocks because this available money effectively flows through the capital markets. … How that affects the markets, I just don’t know. I’m not eagerly anticipating the answer, but I think it holds some surprises in 2010, not just in mortgage securities but stocks as well. We could miss the money, put it that way.”

I didn’t realize that the Fed can purchase things like MBS directly by creating the money to do so. My understanding had been that the Fed swaps reserves for collateral on loans in OMO, rather than making purchases as a principal. Wouldn’t that qualify as spending and have to offset $4$ by Treasury borrowing according to US law? Is this not figured into the deficit? What does the accounting look like for this? Is it a straight exchange of MBS as Fed assets for reserves as Fed liability, and add to M0? Is this part of the Fed’s emergency powers? Thanks.

Hey, come on Prof. Bill.

Tom Hickey’s question is just a little nuanced on the difference between real government obligations and those that are only contingent liabilities because the Fed creates the ($USD loan) money out of nothing to make the PIMCo purchases.

Good education opportunity, I think.

Or is it covered somewhere else?

respectfully.

Billly writes: “It is clear that from any perspective this lobbying led to a “misallocation of resources” which means that financial markets are not good judges of the best use of a society’s resources nor provide effective discipline to ensure the socially optimal configuration of private (and public) spending is achieved.

Anytime you hear some economist say that private markets allocate resources better than the government you should just laugh”

I read this exactly the opposite. Your example is exactly a point that financial institutes + government don’t allocate resources efficiently. I’m not at all a believer in financial markets being optimal, but to claim that governments are somehow better is bordering on the insane. Of course the finance industry is going to lobby for more resources to be allocated in its favour, just like every other industry. They are self interested. The fact that they were successful is more evidence that government should have as little say as possible in such decisions. Without the help of the government, they would not have been able to do much of what they got away with. The fact that governments are not benevolent means that they will act in their own self interest as much as those in private markets. The only difference is that the funds they are spending are not their own, so they will be less careful with their decisions.

Dear Timbo

Yes, the government has a role to play. It needs to regulate private economic activity. I would also never say (as you suggest I do) that “governments are somehow better” at allocating resources than the private sector. Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

The point that you acknowledge is that the claim that the financial markets are somehow independent arbiters of optimal resource allocation is false which was my only point.

But then the reason they are successful at lobbying just tells you that there are corrupt officials in government who will distort the legislative pursuit of public purpose in favour of particular sectors who demonstrably have not been “good” for advancing public welfare. It does lead one to your conclusion that “government should have as little say as possible in such decisions”. Financial stability is a public good (as we are seeing in spades during this current crisis) and that requires strong oversight by government.

The other point is that whether you advocate larger or smaller government is a reflection of your ideological position – but you cannot escape the essential issues that modern monetary theory raises in terms of the monetary relationship between government and non-government and the implications of changes in that relationship for GDP, employment etc. If the non-government sector wants to save then the government sector has to deficit spend up to the desired level of non-government sector or else a recession is the next stop! Like it or lump it, that is strictures of the monetary system we (mostly) all live within. So if you don’t want the government sector to be larger then you better be advocating a low non-government sector saving ratio.

Most small government advocates who also want budget surpluses to be pursuit but like lots of cheap imported goods (so that there is a current account deficit) fail to understand that those aspirations are only possible if the private domestic sector increasingly goes into debt. That is not a sustainable option and ultimately the reversal back into public deficit is very painful

best wishes

bill

Dear Tom

Sorry for the delay in replying. Joebhed stimulated my memory today.

You might like to read this information – http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/mbs_faq.html

The transactions were conducted via some chosen (via tender) investment managers who dealt with primary dealers (those eligible to transact directly with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York).

The MBS bought and held by the Federal Reserve are not eligible for lending through the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) or the daily System Open Market Account (SOMA) securities lending operations.

The purchases are transacted by the creation of additional bank reserves.

It does not figure in the deficit nor should it be because there are not net financial assets being created in the non-government sector. A swap of a MBS for a bank reserve. This is a basic insight provided by modern monetary theory and I have covered it in many previous blogs.

Apparently, and I haven’t read the act before writing this but the transactions are “permitted under Section 14(b) of the Federal Reserve Act”.

best wishes

bill

Thanks for clarifying this, Bill. I had not understood that the Fed has the authority to deal in securities other than Treasuries.

So the Fed simply adds reserves by crediting the liability side of the balance sheet and then debits its assets, which are reflected on the asset side of the balance sheet as the securities purchased. I assume that when the Fed sells the securities, then it simply records a profit, loss, or wash. If there is a loss, this is essentially immaterial since this is not “paid for by taxpayers” as the fiscal scolds claim. It’s just the substitution of one asset (security) for another (bank reserve) on a PD’s balance sheet. Simply a liquidity operation akin to OMO.

However, since QE is a Fed purchase rather than loan, the Fed takes on the exposure to loss instead of the bank. In this case, the bank potentially receives more than the security is worth if marked to market, and the Fed eats the difference if there is one when it sells the security. This isn’t adding anything to the system from the accounting point of view, however, because it is a swap of one type of asset for another. This is important because there is a general perception going around that the Fed is adding to the system by taking the potential (and almost certain) loss instead of the banks, whereas this is not actually the case since there is no change in NFA. Just as the Fed can create reserves, it can uncreate them in taking a loss.

But I understand that the Fed is planning to withdraw liquidity through reverse repos. If it uses non-tsy securities on its balance sheet for this purpose instead of selling them in the market at market price, how are they valued – at the nominal purchase price or market value? If it’s at nominal purchase then the deal is a wash when reverse repo’d, and the PD will takes the loss if there is one on subsequent sale. If not, then the Fed takes the loss.

My question is, then, was the contemplated as a temporary liquidity provision, or was it intended to take some losses onto the Fed balance sheet. The general perception seems to be that the Fed was intentionally absorbing potential bank losses to protect their capital.

If this is correct, I get it. Thanks.

Tom, Bill

Section 14(b) basically allows the Fed to do purchase most anything it wants if it declares that special authority to do so is needed (namely, in a time of crisis). There are some limits, of course, but this is where the authority to do most of the standing facilities comes from.

Note that in the program the Fed is only buying MBS that are backed by the GSEs, so there’s little, if any default risk, and they claim to be doing a buy/hold strategy, so capital gain/loss isn’t an issue either. The purpose of the program was mostly to create a more liquid secondary market to bring down mortgage rates, not QE or to take losses onto the balance sheet (again, the MBS are GSE guaranteed).

Of course, yet again, the Fed missed the point. If they wanted mortgage rates at X%, they should have just announced the rate they would buy MBS at and let qty float. Instead, they announced a qty and let the rate float. It came down at bit, but certainly not any overly significant amount (not enough for it to be worth if to me to refinance, for instance). An even easier method would have been for the Fed to instruct the Treasury to do this, since it owns Fannie and Freddie.

Thanks, Bill and Scott. There is a lot of misinformation flying around, and I’m glad to have this straight in order to be able to pass it on with confidence that what I am saying is correct.

BTW, Randy Wray is out with a post today on Bernanke’s (mistaken) preference for quantity.

Hello Timbo

Have not seen you comment here before, welcome!

I just want to question one of the assumptions you made in your comment to Bill. You said that the govt is not spending their own money as if the money they spend “belongs” to someone else. This is patently false form an MMT perspective IMO. The govt IS the currency issuer and in fact “owns” every cent until they “spend” it and then WE “own” it. We dont own it til after they spend it. The whole language of using taxpayer money as if they are taking something of ours is false operationally and unhelpful politically.

Good day

Thanks, all.

Only thing I am not so sure of is Tom’s conclusion that there is no net liability possible to taxpayers.

First, I kind of think this MBS-GSE-Fed thing should be under Treasury completely.

But I also feel that the potential loss from these transactions can come back to taxpayers from reduced “profit” repatriations back to Treasury. Increasing the deficit. Increasing government borrowings – a taxpayer obligation.

But I know that’s another story.

Question: Assume I take for granted the assumption that the private sector players act in their own best interest. Let’s ignore for a moment the fact that the very existence of government officials allows for bribing in the first place. If we simply look at those countries where the private sector was basically obliterated (Cuba, USSR, Venezuela, North Korea etc) what conclusion is one to draw about the “wisdom” of government control of resources and spending?

Can one point to private sector failures? Certainly, but those companies should be allowed/forced to file for bankruptcy and consumers move on. OTOH, bankrupt governments can keep their citizens captive. They don’t declare bankruptcy, they just slowly bleed the entire economy dry and ban freedom while they’re at it.

Dear Jason

First, I would be careful in lumping this collection together. And further, for example, what do we actually know about these countries, particularly North Korea other than what we read or watch in a loaded anti-socialist media?

Second, Cuba is not going to help your case because its prospects were artificially constrained by mean-spirited and paranoid US government policy. But if you get beyond the biased media coverage and get down on the ground there and see it for yourself, you might be surprised at what they have done there. Better health care than in the US for more people. Excellent education system. Less people (as a percentage) in dire poverty than the US. Excellent sports programs and wonderful music and cultural development. Yes, they are poor generally – and with a total blockade from the US and the collapse of their sugar markets when COMECON collapsed – how would have the US coped with that? Yes, there are political issues – they don’t seem the understand that you can have socialism with zero purges.

Third, Venezuela has not obliterated its private sector.

Fourth, the evidence from the USSR is mixed. I have spoken at length with people who lived in that system – they had secure employment; reasonable housing; adequate food; access to excellent education and health care; good access to cultural sophistication; reasonable retirement benefits etc. Now, especially in the old satellites, the older workers who expected to retire on their pensions have lost them and are paying so-called “market” rents which have forced them out of housing; have poor access to health care, and the education system is in decline. They now vote in elections. Are they better off or worse off? Its ambiguous in the extreme. Certainly not clear cut as you might think.

Fifth, how much freedom does an impoverished black ghetto dweller in one of the US cities really have?

Whether you like it or not – in a fiat monetary system, the government is a central player and an engine for prosperity or the opposite. You cannot rely on the private market for that. It plays a part but has to be supported by public net spending if the private sector desires to save. You cannot escape from that reality of the system you live in. Those who enjoy prosperity should therefore get over the dislike of public activity and make it work better. A strong government always will mean a prosperous private sector.

best wishes

bill

Hey Jason

I’m not sure you are making the right distinction. You need to make a distinction between dictatorships like Cuba, USSR and North Korea and better run ( I wont say well run because that is completely subjective) govts like the US, Canada and much of Western Europe.

I’m not even sure if N Korea and Cuba are sovereign currency issuers. You also seem to think that this blog supports government “control” of the resources and spending. I think that is patently false. In one of his previous blogs Billy talked about how any attempts by central banks to control money supply were futile. They cant do it in the US, Aus, GB and Canada. When a private entity wants a loan and is deemed a good risk by the bank he gets it and that increases the money supply as soon as the new deposit is made (which can be spent) All the govt/CB controls is the prime rate.

The govt can only control its own spending and not all spending. It can use taxation to decrease private demand when necessary (not as a source of its funding) but Im pretty sure even Billy would say the tax policies of most of the world are not sensible. There certainly is plenty of room for finding smarter tax policy.

What I think I can say for most of the MMT advocates is that they believe that sovereign currency issuer should not let fears of govt bankruptcy enter the discussion (as long as the govt is not using anyone elses currency in addition) and that maintaining employment is the best way of maintaining equity values and having stable prices.

The problem I think is not govt vs private sector its people. Good people vs not so good. Smart vs not so smart. Why do we cower at the thought of our govt using monopoly power to control the price of something that is for common good yet we applaud WalMart using its monopoly power to bully its vendors into giving it lower prices than everyone else? I find no difference between the two.

Actually there are way more private sector failures. 80-90% of new businesses fail in the first 12 months, thats a lot. I’m not saying that govt should just employ all these people because I’m in favor of the freedom to chase your dream and start something, however when they “fail” it should NOT mean, no health care and no income. They should stay afloat to fight another day.

Amplifying on what Bill said, an important point that is often missed in all this is that only the monetary sovereign as currency issuer (in the US, the federal government) can increase or decrease non-governmental net financial assets, since since all non-government financial transactions involving credit money net to zero. If government doesn’t provide through currency issuance, non-government NFA = zero.

This implies that the currency issued to create non-government NFA is for public purpose, not the special use of any privileged party. Government spending and taxes come from this provision, not the credit money created by non-government finance. Government borrowing is net to zero, since it is simply the exchange of one kind of asset (tsy’s) for another (bank reserves). although interest paid on government debt, like other types of government spending, increases non-government NFA.

Currency issuance is therefore a public utility provided for public purpose, according to the Preamble to the US Constitution, “the general welfare. The federal government is not only granted the prerogative of monopoly issuance, it has the corresponding responsibility to issue the necessary currency for the general welfare, that is, not only to facilitate commerce but also to provide for pubic purpose.

Hi Greg,

Thanks for the welcome 🙂 I have just discovered this blog. I am a complex systems person, so take a keen interest in these subjects. I remain entirely unconvinced by the benefits monetary and fiscal policy, but reading blogs such as this will (hopefully) help me to keep an open mind.

Your comment about MMT theory is exactly where I differ in opinion from a lot of people. It is true that governments can create new currency and spend it, but this currency devalues the existing currency that citizens hold. Therefore, this is simply a tax on those who hold money (mainly savers), and should be considered as such. The net product is the same. Creating new currency does not increase the amount of resources available. It increases the purchasing power of the people who get to spend it first (in this case the government), and decreases the purchasing power of anyone holding existing money. Furthermore, the increased purchasing power enjoyed by the government is used to buy resources (including labour) from citizens, and at the expense of those few who miss out on the resources due to being priced out by the government spending. This is clearly taking something that would have otherwise been used by the private sector.

My comment that the funds are not their own holds: the individuals within the government do not own government money; i.e., they are unable to go out and buy themselves a new house with it, and when they leave office, they lose any control over it. Yet at the end of the day, the decision made by governments are made by the individuals within the government, not by an abstract entity called “the government”, and can be used to benefit individuals within the government. If they spend it wastefully on pork barreling, this will actually benefit them and the few that they are helping directly. I doubt many politicians would spend their own salary on such wasteful endeavours such as building new school halls that are not needed, and on $900 stimulus handouts. I’d be happy to see them do so!

See you all in future discussions!

Timbo

Dear Timbo

When you say that creating more purchasing power just “devalues the existing currency that citizens hold” you are assuming a perpetual state of full employment. Take a look around you. I think you will see plenty of real capacity that can be taken up if there was nominal demand for it.

Net government spending is not inflationary as a matter of course, just as private investment spending is typically not inflationary.

best wishes

bill

Bill said: <>

OK, firstly, I have been to Cuba. Their infrastructure is rotting away. Burros can still be seen in place of some cars. There are shortages of decent food and the local stores carry very little and prostitution seemed to be the main business in Havana. You can try and blame this as you have on U.S. foreign policy but this is a straw argument. Cuba is free to trade with every other country in the world. (The problem is they have nothing to trade other than sugar and cigars and private production is strictly limited). Their education system seemed good (but this is not that uncommon in dictatorships which use education as a means of indoctrination).

I also have spoken to may folks who fled the Soviet bloc at various times. They don’t have any nostalgia for the way things were. In fact, they are typically rabidly anti-state (and don’t like what they see in the U.S. drift as it reminds them of home).

North Korea??!! YOU MUST BE KIDDING. Have you seen satellite photos of the two Koreas at night? That alone speaks volumes.

All in all, let’s just observe that there is/was no immigration into Cuba, North Korea, and USSR pre-dissolution but lots of people were willing to die trying to escape.

Inflation can happen with “perpetual unemployment” the two are not mutually exclusive. The money printing may not go into food or commodities, but it will go into something (real estate, dot coms etc) and distort market signals. As such, I have the same doubts as Timbo.

“and prostitution seemed to be the main business ”

Sounds a lot like Wall Street.

BTW, this just in on the paradise of Venezuela. If Chavez hasn’t appropriated all private property he’ll just ruin the existing ones. More wonders of socialism. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aTtr11jqdrdM&pos=4

Dear Jason

I think you are confusing my blog with one that seeks to advance the unambiguous benefits of socialism as practised in this imperfect world of “socialist” states.

The specific blog you are commenting on above is about the problems that the misuse (and criminality) of “Wall Street power-bases” around the World have given citizens in all states – most of whom live in capitalist systems.

I would also note that the US has the worst child poverty in the advanced world and it is the largest private economy in the world. There are bad facts everywhere.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

I did get off on somewhat of a tangent, but I initially pointed out that in those countries where the government has control over a significant amount of the economy (which MMT seems to endorse), very bad things happen. You proceeded to defend Cuba, the USSR and somewhat dismissed concerns about North Korea by stating ‘what do we really know?’ and you brushed aside concerns about Venezuela. I countered that these regimes had/have serious problems both economic and perhaps more importantly with regard to freedom. Today’s news on Venezuela comes an no surprise to me. Your take seems to be (and I certainly could be misreading it) that socialism just hasn’t been done correctly yet while I believe it is inherently very flawed.

Dear Jason

Thanks for the comment. I didn’t really defend anything. My point was that things are never as simple as they seem. I have no doubt that if I was offered residency in North Korea I would decline. In the case of the USSR, the work I have been doing in the Central Asian republics with the Asian Development Bank highlights a mixed bag. Many older people are disenfranchised and are feeling lost in the market economy whereas the younger generation have embraced it. Cuba – that is another story.

In terms of MMT we should be clear that it endorses no specific size for the public sector – significant or otherwise. My ideological preferences might be for a larger government sector than other people (perhaps yourself) would desire but that is a separate matter.

What MMT tells us is that for a given size of the non-government sector then to have full capacity utilisation of resources the government then has to be of a particular size. It also tells us that if you try to cut the size of the government sector when the private sector are wanting to spend less on real goods and services then you will end up in a poor situation. This also means that the budget deficit is largely endogenous and driven by the saving desire of the non-government sector.

I often tell business people when I am giving talks – if you don’t like the size of the deficit then there is a simple way that you as a sector can deal with it – spend more!

best wishes

bill

Thank you for your responses. On another issue (hinted at in an earlier post above), inflation is one of my big concerns with the adoption of MMT policy. Since it was clearly established in the 1970s stagflation era that inflation can happen even with sub-optimal growth and employment, can you point me towards any writings on MMT and the inflation issue? Like another reader above, I have concerns about the government devaluing the currency with too much money printing. After all, currency should not just be a medium of exchange, but it should be a store of value as well.

Jason,

“After all, currency should not just be a medium of exchange, but it should be a store of value as well.”

Should it really be? Don’t you think it is a gold age left-over? What is your personal share of savings in currency (by which I assume you mean cash)? Liquidity – yes, store of value – hardly so any more. However with bank overdrafts and credit cards even liquidity argument is much less important.