The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Treasurer-central bank stoush – a case of the pot calling the kettle black

The Reserve Bank of Australia has certainly attracted headlines this last week or so starting with the claim by the Federal Treasurer that the monetary policy stance is “smashing the economy” (Source), while a past Labor Treasurer and now Labour Party National President (Wayne Swan) was much more openly critical of the RBA conduct over the last few years. Things then came to a point when the new RBA governor gave a speech the day (September 5, 2024), the day after the National Accounts came out with the news that the GDP growth rate had slumped to 0.2 per cent for the June-quarter (well below trend), and told her audience (a Foundation that “supports research into adolescent depression and suicide”) that around 5 per cent of mortgage holders were falling behind payments and many would “ultimately make the difficult decision to sell their homes” (Source) as they would be forced into default. Meanwhile, the conservatives (and economists) have claimed the Government is impugning the ‘independence’ of the RBA. It is a case of – The pot calling the kettle black – and demonstrates how ridiculous the policy debate has become in this latter years of the neoliberal era.

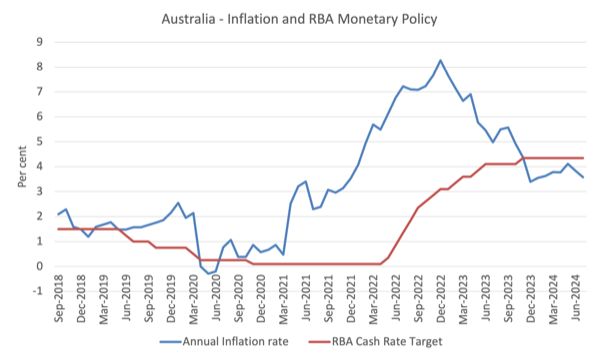

The following graph is a good reference for the debate.

It shows the annual inflation rate and the trajectory of the RBA’s cash rate target (its monetary policy interest rate choice) from September 2018 to July 2024.

The graph shows that the recent inflationary episode began in early 2021 and the RBA did not respond until May 2022 when it raised the rate from 0.1 per cent to 0.35 per cent.

Then followed 11 rate hikes over the new 13 months.

But note that the inflation had peaked in December 2022 yet the RBA continued to hike rates until its last increases in November 2023.

The RBA still claims it might hike again.

Several things are pertinent:

1. Early on in the episode, the RBA claimed that the inflation was spawning a wages breakout – they said their private business consultations told them that – and that the rate hikes were necessary to head off that wages explosion.

Of course, the wages data showed otherwise and eventually the RBA stopped hiding behind that ruse.

2. Then the RBA has claimed that there is excess demand (spending) in the economy that needed to be expunged by the interest rate rises.

Again, they claimed that business briefings were telling them that price pressures remained in the system.

Yet, last week’s National Accounts data showed private spending was going backwards – household consumption expenditure contracted in the June-quarter and that GDP growth was well below its trend rate (meaning there is excess capacity in the system).

It is hard to say there is excess spending when the economy is contracting.

3. Some commentators are now focusing on the delay in increasing rates and reducing them again (as the graph shows) as evidence the monetary policy process is chaotic.

The current Treasurer’s comments about the RBA “smashing the economy” were all about him trying to get in before the National Accounts data came out last Wednesday (September 4, 2024), which showed how badly the GDP growth rate had declined over the last few years.

With the economy now on the brink of recession and the only source of expenditure still driving positive GDP growth being from the government, Chalmers knew the Government was in the firing line.

And the Government is facing a general election within the next 6 months and it is polling badly because it has done very little in the last 2.5 odd years.

So what best to do – deflect the blame to the so-called independent central bank, the RBA.

A classic case of depoliticisation.

The past Labor Treasurer and now Labour Party National President told the media (Source):

The Reserve Bank is putting economic dogma over rational economic decision-making. Hammering households, hammering mums and dads with higher rates, causing a collapse in spending and driving the economy backwards doesn’t necessarily deal with the principal pushes when it comes to higher inflation …

I’m very disappointed in what the Reserve Bank is doing at the moment … If you look at markets, they’re all forecasting rate drops. They’re going down around the world …

The government is doing a lot to bring down inflation, but the Reserve Bank is simply punching itself in the face. It’s counterproductive and not good economic policy.

It was a coordinated attack by the Government on the RBA even if they denied that.

Chalmers was a principal Treasury advisor to Swan when the latter was Treasurer in a previous Labor government.

I actually agree with Swan’s comments – but while he was the Treasurer he did nothing to change the way the RBA operates – when he could have – and was part of the choir that told us how good it was to have an independent central bank who would fight inflation.

On September 6, 2024, another former Treasurer, this time from a past Conservative government (Peter Costello) answered the criticism by daring the Government to alter the RBA’s inflation targetting band (Source):

They’re working to the target he’s agreed to … If he doesn’t like it, then change it. He could change it tomorrow.

That was just further noise from a past Treasurer who oversaw the massive buildup of private sector indebtedness in Australia as he squeezed the economy with 10 out of 11 years of fiscal surplus.

4. What the graph demonstrates is that the inflationary episode was fast to accelerate and also fell fairly quickly.

The claims that it was an excess spending event are difficult to sustain.

The rising inflation was due to the extreme circumstances that the global economy encountered as the pandemic unfolded.

The supply constraints, then the Ukraine impact on supply, then the brief OPEC+ price gouging in the face of income support being provided by governments for workers forced to stay at home during the early years of the pandemic were always going to cause inflationary pressures.

Once the global economy worked through the constraints – either finding alternative sources of commodities or as the restrictions were lifted, the inflationary pressures succumbed as the graph shows.

The Bank of Japan demonstrated that through this period there was no reason to raise interest rates as these transitory factors would resolve themselves – as they did.

Further, the persistence of the inflation in Australia just above 3 per cent is in no small way being driven by rental costs – which are directly the result of landlords passing on the interest rate increases of the RBA.

The alleged ‘inflation fighting monetary policy’ becomes a source of inflation.

5. The Australian experience is also quite different to the US experience.

In this blog post – RBA governor’s ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ moments of disdain (June 8, 2023) – I discussed those differences.

Some think that the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position is that interest rate rises are always stimulatory.

Warren Mosler certainly articulates that view based on the US experience.

In fact, there is no single – applies in all situations – MMT rule on this.

In general, MMT economists note that monetary policy that relies on interest rate adjustments is uncertain in impact because, in part, it relies on distributional consequences whose net outcomes are ambiguous.

Creditors gain, borrowers lose.

How does that net out?

Not sure.

We also point to the likelihood that interest rate increases will have inflationary impacts via the impact on business costs and landlord borrowing costs.

But, there is some nuance that has to be applied when considering temporality – that is, the impacts over time.

My position – based on Australian experience and history – is this:

(a) No-one really knows whether the winners from the interest rate rises will spend more than the losers cut back spending.

The evidence is that wealth effects on consumption spending are relatively low when compared to the income effects.

But there are many complications – such as saving buffers etc – that make it hard to be definitive.

(b) In the immediate period after the interest rate rises, the spending responses from debtors is likely to be restrained because they have capacity to absorb the squeeze by adjusting their wealth portfolios (run down savings etc).

And, at that temporal period, the interest rate rises are likely to be inflationary as businesses pass on their increased borrowing costs in the form of higher prices, and, as noted above, landlords pass on their higher mortgage servicing costs as higher rents, which, in turn, feed into the CPI figure.

(c) But in the medium- to longer term, if interest rate rises move past some threshold, the impact is to slow spending and increase unemployment.

Eventually, those who benefit from the interest rate increases, who typically have a lower marginal propensity to consume (how much they spend out of every extra $ received), run out of things to buy and pocket the bonuses.

And eventually, the spending cuts from the debtors, particularly lower income mortgage holders, begins to dominate.

There are three other considerations:

(a) The level of household debt – the higher the debt, the more the negative impacts of the interest rate rises will be on spending.

(b) The proportion of population that has mortgage debt – the higher the proportion the more likely it is that the medium- to longer-term effects will become dominant.

(c) The proportion of mortgage debt that is fixed rate compared to variable rate.

Australia has a high proportion of variable rate mortgage debt, compared to, say the US, where most of the housing debt is fixed rate.

Australia also has a relatively high level of household debt.

So while the interest rate rises were unnecessary in terms of dealing with the inflationary pressures – given they were not of the excess demand variety – they have finally started eating into the total spending and output in Australia and helping to drive the economy towards recession.

I gave an interview for the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) in Australia last week along these lines following the release of the National Accounts data – Australia’s economic head is ‘barely above water’. Here’s how that’s affecting you (September 4, 2024).

But it should also be noted, and this is the ‘pot calling the kettle black’ aspect of all this – which is not discussed in the media at all – fiscal policy is excessively tight at present.

Since elected in May 2022, the current federal government has run two years of fiscal surplus, at the same time as interest rate have been rising.

The fiscal contraction is a much more powerful constraint on non-government spending than the interest rate rises and the combination of the two has killed economic growth.

So it is a bit rich for the Treasurer to blame the RBA for the near-recession state of the economy.

6. What the RBA can be cited for though is that it has turned monetary policy into a vehicle for engineering a massive regressive redistribution of income from poor to rich.

We usually think of fiscal policy as being vehicle for shifting income redistribution from the market outcome to the post-policy outcome.

And we usually think of that process in progressive terms – that is, increasing equity – transferring income from high to low – through fiscal transfers and progressive income taxation.

But what has happened in recent years in Australia (and elsewhere) given the high levels of non-government debt outstanding is that monetary policy has become a major tool for redistribution and not in a progressive way.

Low-income mortgage holders with massive debt liabilities (given the real estate booms have pushed up housing prices) are now paying an increasing proportion of their income to service their mortgage debt courtesy of the RBA rate hikes.

While financial asset holders and creditors (typically higher income cohorts) have been reaping an income bonanza as rates have risen.

In the US, for example, for reasons explained above, this redistribution has not killed growth by as much as it has in, say Australia.

It also shows the perversity of giving to much latitude to monetary policy – it becomes a case of the government lining the pockets of the top-end-of-town and taking loads from the poorer strata of society.

And it doesn’t help for the RBA governor to wax lyrical during her speech the other day about the RBA being aware of how tough low income families are doing it.

Conclusion

The upshot of all of this is that macroeconomic policy is not currently operating to advancing the well-being of the citizens.

It is skewed towards an errant monetary policy that is chasing shadows but causing real harm to low income families and a fiscal policy that is too tight given the longer-term challenges that the nation faces (housing shortages, rising poverty, climate change, degraded health and educational systems).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you Bill for this explanation. It clarifies (with a real world example) the “controversy” over if and when interest rate hikes are inflationary. There are many opposing factors, which also depend on the context of each country. I guess it’s better not to use categorical affirmations about the effect of interest rate changes and look more closely into the details of each country.

I think SMSF (Self-manage Super Funds) has done quite a lot to increase property prices,

Oddly, enough it’s rarely mentioned by the media or anyone as a problem.

But if you look at what happened to property prices when the Coalition allowed investment properties to be purchased through SMSF’s in 1999 it’s undeniable.

Then you get to 2007 and the changes the Howard Government made to (Section 67 (4A) of the SIS Act). Now people could also borrow to buy properties and add them to their SMSF portfolio,

No prizes for guessing how that impacted property prices.

The ALP and Coalition are both to blame – Coalition might have implemented the changes but the ALP did absolutely nothing to stop it.

Some of these SMF funds have over $50million in them – many of them are between $20m-$50m….

Sure, the RBA are terrible – but the way both major parties now lay blame on the RBA and are silent on how their Tax and Super policies fueled the housing booms is hypocrisy of the highest order.

I think interest raises have potential, depending how asset purchases are financed, potential to have significant effect on asset prices, and hence, via wealth effect, aggregate demand.

For example if economy has people who have funded investment in rental property with debt, and they are highly leveraged and when the interest rate raises they have to sell their properties because the rental income does not cover the interest expense that has effect on supply and demand of houses and therefore prices of houses.

This is very economy dependant. Nothing universal can be said about effect of changes in interest rates on aggregate demand.

Thank you for the nuanced explanation of the overall effects of interest rate rises.