I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

RBA governor’s ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ moments of disdain

The RBA governor had a few ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ moments in the last week when he responded to criticisms that his manic interest rate increasing behaviour is driving low-income families into crisis by, first, saying that people who couldn’t find cheap housing should move back with their parents. Then he followed that with the recommendation that people should work harder and get second jobs if they couldn’t make ends meet as a consequences of the squeeze on their mortgage payments from the RBA’s monetary policy changes. Nice. This is an extraordinary period of policy chaos – we have an out-of-control central bank pushing rates up and using various ruses (chasing shadows) to justify the hikes, when inflation is falling anyway for reasons unconnected to the monetary policy shifts. All the RBA will succeed in doing is increasing unemployment and misery. The unemployed will ultimately bear the brunt of this chaotic policy period. But then ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ and they can move back in with their parents!

RBA policy decisions over the long-term

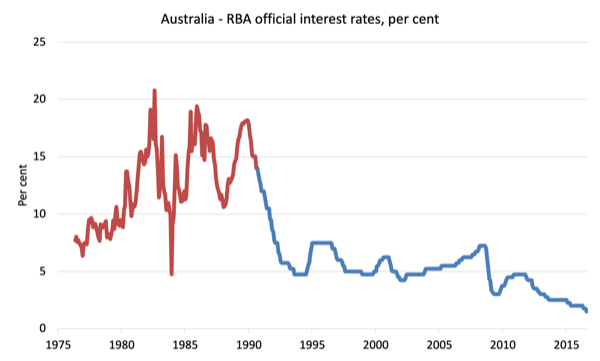

The next two graphs show the interest rate policies of the RBA since the mid-1970s.

There are two graphs because the currently available data was published differently after January 2011 (daily basis) whereas the first graph is monthly in frequency.

Further, for the first graph, the RBA’s Cash Rate Target data (blue line) began in August 1990 and the data prior to that (the red line) is, in fact, the monthly average of the Interbank Overnight Cash Rate, which closely follows the Cash Rate Target.

By splicing the two closely-related series together we get a better picture of the period leading up to the 1991 recession, which was caused by excessive interest rate increases coupled with the pursuit of fiscal surpluses by the then, Labor government.

You also see in the period around the GFC how the RBA was pushing rates up just before the crisis claiming that a major inflation outbreak was about to occur and then were forced into a major policy reversal by the financial collapse and then, without justification, before any recovery had occurred in the real economy, starting pushing up rates again, claiming again that they were worried about the potential for inflation.

That premature tightening was abandoned in 2011 as the economy slowed dramatically and the risk of a recession increased.

The point is that the culture of the RBA biases them to knee-jerk policy responses which are often shown by the facts to be excessive and wrongly directioned.

The second graph shows the daily data from the beginning of 2011 to the current period (last observation June 7, 2023).

What you glean from this data is the rapidity of the tightening in the current cycle.

The current rate hike period is one of the fastest escalation of rates in the RBA’s history.

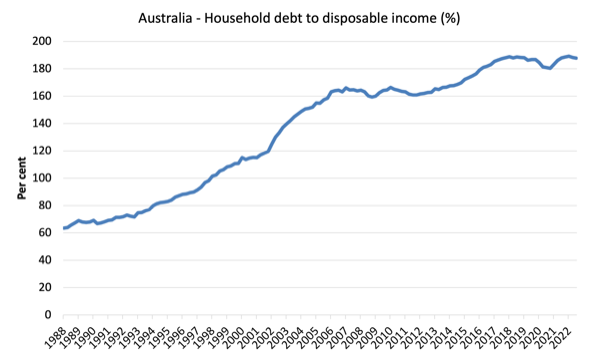

The difference now – as shown in the next graph – is that Australian households are carrying record levels of debt relative to their disposable incomes and have very little room to move, especially at the bottom end of the income distribution.

Considering the two interest rate graphs alongside the debt graph, we realise that while monetary policy tightened massively in the lead-up to the 1991 recession, the burden of those interest rates changes on household viability compared to the tightening now was actually lower because the debt levels were lower.

The average mortgage balance was quite low in the 1980s compared to now.

The degree of vulnerability to insolvency and foreclosure is much higher now.

Elite disdain

When the French philospher Jean-Jacques Rousseau published his 1790 (English version) autobiographical book – Confessions – he recounted the story of a “great princess” who “when told that the peasants had no bread, replied ‘ Then let them each brioches’.”

This has become reduced to – Let them eat cake – and is often attributed to the last Queen of France Marie Antoinette, although that attribution is clearly wrong given she was aged nine at the time the quote entered the lexicon and had not even ventured to France by then.

But the general intent of Rousseau was to illustrate the sheer disdain and dislocation that the elites had for the workers, the poor, those who struggle to make ends meet.

I thought about Rousseau’s Confessions, which I studied at university, in the last week when the RBA governor made several extraordinary intrusions into the public sphere.

First, people are starting to realise that the RBA itself is causing the persistence of the inflationary pressures because they are pushing landlords into raising rents, which are a significant weight in the CPI.

I analysed that link in detail in this post – RBA loses the plot – Treasurer should use powers under the Act to suspend the RBA Board’s decision making discretion (May 3, 2023).

There is a rent crisis in Australia now and the RBA is making it worse.

As mortgage rates rise, landlords are using their ‘market power’ to push up rents significantly to protect their real margins and probably gouge some higher mark ups.

When confronted with reality last week, the RBA governor denied the monetary policy tightening was contributing to the problem and instead offered a sort of quasi-psychological, quasi-sociological explanation.

Apparently, we have adopted lifestyles where we don’t crowd into houses – fit as many people as can possibly fit and then some.

Further, we should be staying with our parents for longer.

He said:

As rents go up, people decide not to move out of home, or you don’t have that home office, you get a flatmate … Higher prices do lead people to economise on housing …. Kids don’t move out of home because the rent is too expensive, so you decide to get a flatmate or a housemate because that’s the price mechanism at work …

We’ve got a lot of people coming into the country, people wanting to live alone or move out of home …

So all you characters out there who want some space or want to mature and leave your family home or face domestic violence and have to live alone suck it up and listen to the RBA governor and squeeze in.

Maybe see if he will offer you a bedroom in his own house.

And remember he was able to purchase his then $A1.075 million house in inner Sydney in 1997 courtesy of a home loan provided by the RBA itself which “was locked at half the standard variable rate” (Source).

If that little ‘mangent de la brioche’ moment wasn’t enough for one week, the RBA governor addressed the financial elites in Sydney yesterday and told the gathering that (Source):

… struggling Australians can cut back spending or pick up more work to reduce financial stress …

The stress being deliberately inflicted by the RBA.

He also claimed that workers should suck up the real wage cuts because “we have to make sure that higher inflation doesn’t translate into higher wages for everybody”.

That’s for sure, eh?

We only want CEOs and other higher income types to get the higher pay, not the rest of us.

What does Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) say about all this?

Of course, the interest rate increases are unnecessary – just ask the Bank of Japan which has held to its low rates since this supply-side inflationary episode started and also seen the fiscal authorities hand out cash to households and firms to get them through the cost-of-living crisis.

I wonder why none of the journalists out there decline to ask the RBA governor to compare his record with that of the Bank of Japan’s record?

But the current period has raised issues relating to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

When I was working in Kyoto last year, I spent a week or so with my colleague Warren Mosler who came across to Japan to catch up with us.

Each lunchtime I would cycle down to his hotel from my office and we would sit out on a rooftop terrace discussing the progress of the MMT project as well as reflecting on all manner of things.

One topic relates to today’s blog post specifically.

I note that there is discussions out on the Internet about the split between Warren’s current position on monetary policy and inflation and the view held by the so-called MMT academics (which must include yours truly).

The point is that there is no single – applies in all situations – MMT rule on this.

In general, MMT economists note that monetary policy that relies on interest rate adjustments is uncertain in impact because, in part, it relies on distributional consequences whose net outcomes are ambiguous.

Creditors gain, borrowers lose.

How does that net out?

Not sure.

We also point to the likelihood that interest rate increases will have inflationary impacts via the impact on business costs and landlord borrowing costs.

But, there is some nuance that has to be applied when considering temporality – that is, the impacts over time.

The crude version of the ‘split’ is that Warren believes the interest rate increases are in actual fact expansionary because they are prompting a fiscal policy expansion via the interest payments on the outstanding debt.

In our discussions in Kyoto, I outlined my position (the ‘academic’ position) like this.

1. No-one really knows whether the winners from the interest rate rises will spend more than the losers cut back spending.

The evidence is that wealth effects on consumption spending are relatively low when compared to the income effects.

But there are many complications – such as saving buffers etc – that make it hard to be definitive.

2. In the immediate period after the interest rate rises, the spending responses from debtors is likely to be restrained because they have capacity to absorb the squeeze by adjusting their wealth portfolios (run down savings etc).

And, at that temporal period, the interest rate rises are likely to be inflationary as businesses pass on their increased borrowing costs in the form of higher prices, and, as noted above, landlords pass on their higher mortgage servicing costs as higher rents, which, in turn, feed into the CPI figure.

3. But in the medium- to longer term, if interest rate rises move past some threshold, the impact is to slow spending and increase unemployment.

Eventually, those who benefit from the interest rate increases, who typically have a lower marginal propensity to consume (how much they spend out of every extra $ received), run out of things to buy and pocket the bonuses.

And eventually, the spending cuts from the debtors, particularly lower income mortgage holders, begins to dominate.

The Australian data clearly demonstrates this temporal effect.

The problem is that when a nation reaches this point, given the delays in data publication etc, the damage is already done.

So in trying to understand these different accounts we have to appreciate several things, which includes:

1. The level of household debt – the higher the debt, the more the negative impacts of the interest rate rises will be on spending.

2. The proportion of population that has mortgage debt – the higher the proportion the more likely it is that the medium- to longer-term effects will become dominant.

3. Crucially, the proportion of mortgage debt that is fixed rate compared to variable rate.

This last consideration is important in understanding why we might consider the dynamics of interest rate rises in the US (which is the basis of Warren’s conjectures) to be different to elsewhere.

On December 14, 2021, the OECD published an interesting Economics Department Working Paper (No. 1693) – Mortgage finance across OECD countries – which provided a detailed breakdown of the incidence of variable versus fixed rate mortgages in the OECD nations as well as other statistics relating the points above.

We learn that:

1. “Homeownership rates and the number of households with a mortgage show large differences across OECD countries …”

2. “Several countries combine relatively high levels of homeownership and low take-up of mortgages.”

3. “Homeownership and mortgage use is substantially lower for young or low-income households … ”

4. “Low-income households spend larger shares of their income on mortgage payments with considerable heterogeneity across the OECD” – Lower income households in the US are less likely to have a mortgage than in say, Australia.

5. In Australia, for example, variable rate mortgages dominate (around 84 per cent), whereas in the US the vast majority are fixed rate (around 2 per cent are variable).

6. The US also has a relatively low mortgage debt service ratio (around 8 per cent) compared to say Australia, which is just below 20 per cent of household income.

If you consider those differences, then we can see why the conduct of the Federal Reserve Bank at present is not likely to generate recession.

The debt levels in the US are relatively high by historical standards, the outstanding mortgages are mostly fixed rate over long durations and held by those further up the income distribution, which means that the rising interest rates are less likely to cause major spending cutbacks from mortgage holders.

Then the higher incomes that the wealth holders gain from the Federal Reserve rate hikes dominate.

But consider Australia (and other nations in Europe, the UK, Canada etc) where the vast majority of mortgages are variable rate and more likely to be held by low-income families, then the rising mortgage payments will squeeze disposable income and ultimately a bust occurs.

In its – Financial Stability Review October 2022 – the RBA conducted a sensitivity analysis on the impact of interest rate hikes on indebted households’ spare cash flows.

They found that:

Interest rate increases of 21⁄2 percentage points … the net effect would be a reduction in monthly spare cash flow (relative to April 2022 levels) of around $1,300 – or 13 per cent of household disposable income.

That was for “a highly indebted household earning $150,000 of gross income (around the median income for a couple family with dependent children) with $800,000 in debt.”

The situation would be worse for lower income households.

But that squeeze is massive and a similar analysis for the US would find a much smaller impact.

So there is no ‘split’ within the MMT ranks on this issue.

The difference is outlook in the present situation relates to the different circumstances that can arise across nations.

One always has to be careful when appraising a situation not to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ analysis.

The world is complex and the nuances are important.

Conclusion

At any rate, the RBA is driving the Australian economy towards recession and forcing low-income mortgage holders to bear the brunt of its misconstrued fight against inflation.

Inflation in Australia has been falling for months now for reasons unrelated to the monetary policy changes.

All the RBA will succeed in doing is increasing unemployment and misery.

The unemployed will ultimately bear the brunt of this chaotic policy period.

But then ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ and they can move back in with their parents!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’ve always used the phrase, which I think came from Bill, that interest rate changes have ‘uncertain distribution characteristics’.

But this issue does shed some light on why mainstream are obsessed with ‘debt to GDP ratios’. The higher the debt to GDP ratios the more interest rate rises add to interest income flows. This is exacerbated when much of the ‘debt’ is index linked and responds automatically to changes in inflation. The UK’s index linked debt has contributed to a 4% of GDP injection – larger than the energy subsidy – which has pretty much offset any reduction in flow from any contraction in mortgage lending.

Only 20% of UK mortgages are on floating rate. 80% are on fixed rate, but largely short term. Estimates are that a quarter of those fixed rate mortgages will have expired by the end of 2023. The rate on new mortgages has moved substantially – 1.6% to 4.5% if the BoE figures are to be believed – but outstanding rates on the fixed rate majority have hardly moved at all yet: 2% to 2.3%.

The main impact so far is a 30 to 40% reduction in housing production in a country that is desperately short of accommodation to house a rapidly expanding population. That’s real output that is gone forever. This approach creates a boom/bust scenario in housing production meaning that viable career development in the area can never happen – one of the reasons houses are still ‘hand built’ in a manner little different from the 19th century. It’s no wonder they leak energy like a sieve.

Interest rate changes are like trying to steer a car by having the kids in the back seat shift their weight around from left to right. Even though there is a driver in the front seat and a perfectly good steering wheel available.

Monetarism responded to the 1970s by putting the driver in a straitjacket and then, when that didn’t work, taped up the driver’s mouth so those in the back seat could writhe around ‘independently’.

It’s time to take the straitjacket off and tell the kids to sit still.

“5. In Australia, for example, variable rate mortgages dominate (around 84 per cent), whereas in the US the vast majority are fixed rate (around 2 per cent).”

Should that be 92% for the US? Or some other figure?

Getting a bit far afield from the discussion of mortgage terms, but—what do you think has been the impact of short-term rentals on real estate markets? I guess the other thing I don’t know is, over here in the US of A, what the breakdown is between residential and commercial mortgages vis-à-vis short-term rentals. After all, commercial mortgages tend to have very different terms from residential, including terms that are more interest rate sensitive…

I’m somewhat skeptical of the inflationary effects of interest rate increases on the income side because most of that additional income accrues to people who won’t spend it, or at least their increased spending won’t compete with my spending and raise my prices. But then I haven’t seen evidence that interest rates have much effect either way. As you say, it’s complicated, and reviewing some of the ways that it’s complicated was useful, so thanks.

“Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”

Milton Freidman claimed that the severity of the Great Depression was caused by the US Federal Reserve’s monetary policies.

It seems that the historical lesson may in fact be to let the market sort itself out since we never seem to get the interventions right.

I don’t know if MMT would change anything.

I too noticed the RBA Governor’s arrogance and disdain towards young renters and not only to young renters. It is disgraceful and so completely out of touch. It shows why these pampered, disconnected elitists should never be let near public policy. They so clearly have nothing but a complete lack of respect for real workers and have obviously never done a tap of real work themselves. They are the real bludgers and parasites in our society along with their capitalist and rentier mates.

Hi Bill,

What I really like about your work is that is has a basis in the real world and delving into what the figures actually mean. In this piece for example the differing effect likely with different levels of mortgage type. I have been watching some debate between economists and find that they are very black and white rule types of guys. By that I mean they think that inflation is caused by “whatever the text book says” and to stop it you must raise rates until unemployment hits x%. All very godly and hands off.

There is also some commentary regarding house pricing ATM and that pure upzoning and dropping regulatory standards will fix it. After 35 years in the building industry it is clear to me that they have never been in a developer meeting discussing which sites to buy and how they can game the system. Unless they are being disingenuous and acting as a front for developer friends and using their position to do it? The solution is far more complex, but a good start would be to increase public housing back to 1981 levels which would add about 120,000 houses into the market. Given private building is probably about to tank with the changed interest rates this would also be a great time for govt investment, counter cyclical and hopefully not inflationary?

Lastly, word on the street from the local post office that relies on parcels for income is “people are doing it tough and really pulling back, we are stuffed”

I’ve never seen it as a contradiction or a split.

@Darren, do you realize that your post has no meaning, because the subject of the sentence is “it”, and the ‘it’ could mean anything?

Government investment will be inflationary if it has to compete with households and businesses for resources unless it reduces the demand by households and businesses for those resources through taxation. State and local governments will be impacted since as currency users that behave like households and businesses.

All economic players (Federal/State/Local governments, businesses and households) are constrained by the availability of resources. All players except the Federal government as the currency issuer are money constrained.

The Federal government, however, regardless of the macroeconomic theory it chooses, cannot spend at will. It is always constrained by the fear of causing inflation and unemployment.

There are no guarantees that unemployed labour can be utilised since their utilisation implies the availability of unconstrained materials and services, which may not be the case.

I don’t think that the competition for resources can ever be avoided and that means that periods of inflation and unemployment cannot be avoided.

All the Federal government as the currency issuer can do is to guarantee a stable monetary framework and provide unemployment support payments that are non-inflationary except when we are in a deflationary period, where supply (materials, services, people) is greater than demand.

What state and local governments can do is as little or as much as households and businesses.

Fantastic clarification of the uncertain impact of interest rates on aggregate demand. Thank you. Makes a lot of sense.

That RBA governor is such a stereotypical member of the privileged elite is he not? High rates for the plebs and mates rates for himself. What a cliché – socialism for the rich, capitalism red in tooth and claw for the poor etc etc. Hope he enjoys his Sunday morning brioche cause he can certainly afford it.

@steve_american – It is funny you say that, as Grammarly typically tells me the same thing when I use the word “This”.

However, given the context in the blog post is as follows:

“I note that there is discussions out on the Internet about the split between Warren’s current position on monetary policy and inflation and the view held by the so-called MMT academics (which must include yours truly).

The point is that there is no single – applies in all situations – MMT rule on this.

In general, MMT economists note that monetary policy that relies on interest rate adjustments is uncertain in impact because, in part, it relies on distributional consequences whose net outcomes are ambiguous.

Creditors gain, borrowers lose.

How does that net out?

Not sure.

We also point to the likelihood that interest rate increases will have inflationary impacts via the impact on business costs and landlord borrowing costs.

But, there is some nuance that has to be applied when considering temporality – that is, the impacts over time.

The crude version of the ‘split’ is that Warren believes the interest rate increases are in actual fact expansionary because they are prompting a fiscal policy expansion via the interest payments on the outstanding debt.”

My intent should be clear.