In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Some debriefing on continuous fiscal deficits and debt issuance

A government cannot run continuous fiscal deficits! Yes it can. How? You need to understand what a deficit is and how it arises to answer that. But isn’t a fiscal surplus the norm that governments should aspire to? Why frame the question that way? Why not inquire into and understand that it is all about context? What do you mean, context? The situation is obvious, if it runs deficits it has to fund itself with debt, and that becomes dangerous, doesn’t it? It doesn’t ‘fund’ itself with debt and to think that means you don’t understand elemental characteristics of the currency that the governments issues as a monopoly. These claims about continuous deficits and debt financing are made regularly at various levels in society – at the family dinner table, during elections, in the media, and almost everywhere else where we discuss governments. Perhaps they are not articulated with finesse but they are constantly being rehearsed and the responses I provided above to them are mostly not understood and that means policy choices are distorted and often the worst policy decisions are taken. So, while I have written extensively about these matters in the past, I think it is time for a refresh – and the motivation was a conversation I had yesterday about another conversation that I don’t care to disclose. But it told me that there is still a lot of work to be done to even get MMT onto the starting line.

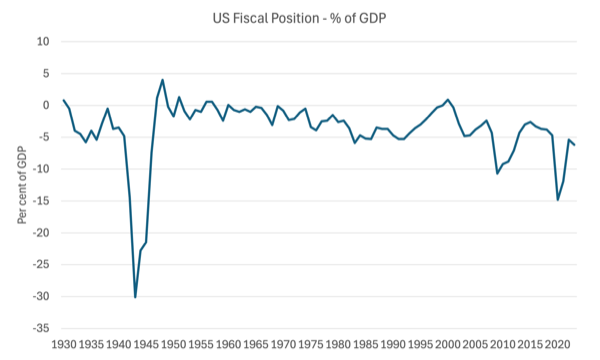

Consider the US federal government, for example.

The following graph shows the fiscal position for the US government from 1930 to 2023 as a per cent of GDP.

What do you observe?

The – historical data – shows that between 1930 and 2023, the US government ran deficits in 81 of those 95 years – or 85.2 per cent of the time.

And the other fact is that each time, the fiscal balance went into or close to surplus, an economic contraction followed soon after.

That data is indisputable.

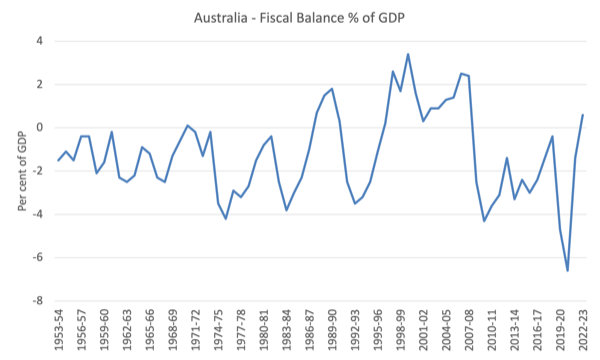

Have a look at the Australian federal data (available HERE).

The following graph shows the fiscal position for the US government from 1953-54 to 2022-2023 as a per cent of GDP.

The data currently provided by the government goes back to 1970-71, but the RBA also provides some historical data that allows us to go back to 1953-54.

What you see is mostly deficits.

In the late 1980s, when the then Labor government became obsessed with neoliberalism and the sanctity of surpluses, they recorded four years of surpluses which ended in the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

From 1996, the Conservative government, similarly obsessed, recorded consecutive surpluses until they were thrown out of office in 2007.

That brief period in our history has been held out by commentators as the ‘norm’.

But as the graph shows, it was an exceptional period in Australian government financial history.

And moreover, it coincided with the massive build up in household debt – from 51.4 per cent of disposable income in 1996 to 163.5 per cent by the time they left office in 2007.

That ratio is now around 186 per cent as governments continue to pursue austerity.

And we should understand that the two happenings – the fiscal surpluses and the rise in household debt – are intrinsically related.

The pursuit of fiscal surpluses from 1996 coincided with extensive financial market deregulation which saw an explosion of bank credit being absorbed by the household sector.

This was also a time that real wages growth was being suppressed through harsh industrial relations legislation designed to kill off trade unions and shift the balance of power firmly in favour of the employers.

The point is that the only way those fiscal surpluses were able to be recorded over the lengthy period (slightly over a decade) was because economic growth (and the resulting tax revenue growth) was maintained by the increase in household sector indebtedness, which allowed households who were being squeezed by the fiscal austerity and the real wages suppression to maintain growth in household consumption expenditure.

Had the households not built up that debt and used credit to maintain their expenditure growth, the economy would have tanked badly a year or so after the first surplus was recorded in 1996-97 and the fiscal position would have shifted back into deficit quick smart.

The other point to appreciate is that basing a growth strategy on fiscal surpluses and ever increasing indebtedness of the non-government sector is unsustainable as we saw when the GFC hit.

Households, in particular, cannot continue indefinitely to accumulate ever increasing levels of indebtedness.

Eventually, the balance sheet positions become so precarious that minor shifts in economic fortune – such as a rise in unemployment, a loss of casual working hours, or an increase in interest rates – sends the sector into crisis and cut backs in expenditure growth follow soon after.

Those cutbacks plunge the economy into recession, which is accentuated by the build up of fiscal drag resulting from the surpluses.

Those who try to characterise that period of Australian history as the ‘norm’ which all other outcomes should be judged against completely misunderstand these relationships and dynamics.

The ‘norm’ for Australia is characterised by fiscal deficits.

The data shows that between 1953-54 to 2022-2023, the Australian ran deficits for 52 of the 74 years or 74 per cent of the time.

If we excluded the ‘abnormal’ years when household debt was rising dramatically and the household saving ratio plunged below zero, then that proportion rises to 90 per cent of the ‘normal’ time since 1953-54.

So what about context

The macroeconomic sectors are interlinked – government, external and private domestic.

The net spending decisions and outcomes of each reverberate on the others.

This allows us to understand the context in which fiscal policy must be framed.

For example, in Australia’s case, as a capital importing nation, our external balance is typically in deficit – which means there is a net spending drain from the local economy to the rest of the world.

That means that some of the income that the economy produces each period is lost to the domestic spending stream – it leaks out to the rest of the world.

That leakage has been, on average around 3 to 3.5 per cent of GDP since the 1970s.

What are the implications of that?

First, if the private domestic sector (households and firms) desire to save overall, then the government sector must target fiscal deficits or else a recession would follow and the fiscal position will be forced into deficit.

Example:

1. External leakage 3.5 per cent of GDP.

2. Private domestic leakage (from overall saving) 2 per cent of GDP.

3. For national income to remain unchanged, the fiscal position must at least offset those leakages with a commensurate injection of net spending – that is a deficit.

Whenever there is an external deficit, the fiscal position must at least equal that deficit or else the private domestic sector will be forced into deficit and increasing indebtedness.

That should help you understand what represents the ‘norm’ for a nation.

In the case of Norway, for example, which currently has external surpluses via its oil and gas reserves, then it can still experience overall private domestic saving with a fiscal surplus, without compromising economic activity and the provision of first-class public infrastructure and services.

Their context is different because the external sector provides a net spending injection as opposed to nations running external deficits which must offset the spending drain with domestic spending injections.

Funding by debt?

Imagine a new country emerges and the government announces it will use a new currency and that all citizens must now relinquish their tax liabilities using that currency.

What becomes the problem?

Simply that the non-government sector, which uses the government’s currency, does not have any of the new currency and will thus be unable to pay their tax liabilities, among other things.

Solution?

The government spends the new currency into existence.

How?

Through procurement processes, pension payments etc.

The non-government sector immediately has an incentive to supply its productive resources to the government in order to earn the new currency.

The sequence is obvious – new currency –> tax liability –> public spending –> tax payments.

Should the public spending exceed tax payments then we record a fiscal deficit and the non-government sector has a flow of saving (in the new currency) which accumulates as a stock of wealth.

That wealth was only possible because the fiscal deficit occurred – that is, the government didn’t tax away all its spending injection.

Now imagine that the government announces a portfolio choice for the non-government sector: an interest-bearing bond (debt instrument) to replace the currency denominated wealth (from the prior saving).

The non-government sector now might convert some of their currency wealth into interest-bearing bonds and the statistician would record an increase in national debt.

But that would just reflect the portfolio mix in the non-government sector between in this simple case currency holdings and interest-rate bond holdings.

Where did the funds come from that allowed the non-government sector to purchase the government debt?

Answer: Prior savings accumulated as currency wealth.

Where did that wealth come from?

Answer: Prior fiscal deficits – government spending not fully taxed away.

In other words, it was the fiscal deficits that provided the funds for the non-government sector to purchase the government debt.

On what planet would we construct those dynamics and causalities as the ‘debt funding the deficits’?

The logic doesn’t change when we complicate the story with real world institutions and behaviours.

Governments do not need to issue debt in order to run fiscal deficits.

The debt issuance does not fund the government deficits.

Mainstream economists say that if the debt is not issued there would be accelerating inflation – their so-called ‘money printing’ case which they eschew.

But that is also nonsensical as a rule.

Given we understand the decision to purchase the government debt is a portfolio choice on desired mix of different components of the wealth holdings in the non-government sector, it should be clear that the ‘funds’ were not going to be spent into the economy anyway.

And if the fiscal deficit injection pushed total expenditure beyond the capacity of the economy to respond (from the supply-side) by increasing production, then we would consider that an imprudent policy position, but, equally, one that is easy to change – cut the expansion.

Conclusion

The principles are clear:

1. Governments can run continuous fiscal deficits forever and the desired magnitude will depend on the context.

2. Governments which issue their own currency do not fund their deficits with debt issuance. The deficits, rather, fund the capacity of the non-government sector to net save, which then allows for wealth portfolio choices, that might include the purchase of government debt.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi

The role of commercial banks in the process confuses me.

A new country and currency is formed, Government imposes tax liability in the new currency and spends directly, the non-Government accumulates wealth, offers people choice between cash or bonds.

“In other words, it was the fiscal deficits that provided the funds for the non-government sector to purchase the government debt.”

But isn’t there also commercial bank lending? A bank lends money to a capitalist, the capitalist pays workers, the worker then purchases Government debt using the money created by the commercial bank.

I know bank money and Government money are separate but isn’t the central bank obliged to provide the commercial banks with Government money for interbank/Government payments?

@Sidharth..

Bank lending is best thought of as providing elasticity in the money supply issued (spent) by Gov. Only Gov spending creates net financial assets (cash etc.) in the non-Gov sector.

Banks must either have accumulated money the Gov spent in Central Bank ‘reserves’, or ‘settlement’, accounts or borrowed reserves from the central bank, in order to make payment/transfers to other banks on behalf of their customers. The Central Bank is part of Gov, so in system terms, banks still require prior issued Gov funds in order to operate/clear payments.

Banks can lend reserves to each other in order to meet daily clearing to other banks, but if they are scarce, banks & Central Bank will charge interest for them – this is the primary mechanism over the years for central banks forcing a minimum or ‘base’ interest rate level, ensuring just enough Bond sales were made to drain reserves from the system to make them scarce for clearing purposes. (Later, CBs paid interest on reserves to serve the same function.)

Bond interest rates were originally set by CBs/Govs in order to manage exchange rates at some level agreed with other countries, eg. in the post WWII Bretton Woods system (which ended ~1971). Which also had the effect of also limiting Gov domestic issuance net spending/deficit & creating unemployment. The only way to guarantee & sustain full employment is to use fully fiat, floating currency – hence MMT insistence that both fiat currency & a ‘buffer stock’ Gov Job Guarantee is optimal in real output terms.

Workers never buy Gov Bonds of this modern type, which are always in high denomination, tradeable & bought & sold within the finance sector at the aggregated level, mostly by banks themselves. Varying interest rates & maturities creating a de facto casino operation called a Bond market. With floating currencies, there’s no point in doing this at all – it wastes real resources in a useless casino activity, & gives free Gov/CB money to banks & the very rich in proportion to their wealth in cash terms. The very definition of Gov welfare for the rich – no doubt why the unnecessary practice continues in our utterly fake ‘democracies’ (actually rule by rich elites’ mass media narrative control, just as it was in earlier days when religion performed the public brainwashing/propaganda function).

Not to be confused with War Bonds, which were sold to the public in small denominations but at fixed terms & were not tradeable. In practice their PR value was far greater than their value in deferring consumer spending, which was also an original rationale to reduce consumer demand & supposed inflation pressure when supply of consumer goods was curtailed in favour of war production.

“Imagine a new country emerges and the government announces it will use a new currency and that all citizens must now relinquish their tax liabilities using that currency.”

Imagine a new world where countries are simply geographical regions on a map. You wouldn’t issue separate currencies for each region surely? Why not a new single global currency – not transferable or redeemable with previously used currencies? That could never happen – right?

I’m probably a little late in coming to this point where I see money as the problem – what should have been a valuable tool in trading goods and services, has become our sole focus in life. The more money we have, the more things we can buy and do => more consumption, more growth => bigger overshoot. If you are advocating the supply of more money – via fiat currencies – to increase govt spending and all the good stuff you espouse – eliminating poverty, improving infrastructure, GND & etc – but using the somewhat corrupt financial system we already have, you’re going to make the problems far worse.

Here’s a thought: try and design a way of life without money. If you don’t think it possible, name me one other species on this planet who doesn’t?

I agree that workers could use part of their savings to buy government bonds. However, most likely this case remains only a theoretical possibility, at least over the past half century, given that wages have been stagnant and decreased in real terms.

I also think it’s much more important to understand that deficits and public debt is a creation of the law. In many countries the law requires the state to finance its deficit by borrowing through bond sales. For a monetary sovereign country this is absolutely unnecessary because as we already know it can never default on its payments, no matter the height of accumulated debt. So, public deficit spending benefits the entire private sector directly by providing the opportunity to net save and additionally the wealthy further gain through swapping sterile cash for interest earning bonds.

As for the CB it doesn’t have any responsibility to provide banks with government money but instead quite often injects liquidity into the banking sector in the form of reserves, in the conduct of interest rates management activities. These reserves are provided either via open market operations, which is the norm, and very seldom when the CB acts as a lender of last resort through the discount window.

Mark, concerning that moneyless economy, by far the most detailed description of it, or at least one version of it, was provided by an American Victorian novelist named Edward Bellamy. I came upon his work late in life and was so blown away that I undertook the impossible task of capturing the highlights of his vision in article form. My unworthy effort, if you’re interested, is still accessible by searching for “on earth as in heaven bellamy.” His two greatest works, Looking Backward and Equality, are free to read on the net. Perhaps the easiest way to determine whether Bellamy appeals to you is to check out the Socratic dialogue between Edith and Julian with which Equality begins.

Many thanks, Newton. I hadn’t come across the writing of Edward Bellamy before, but after reading your most interesting synopsis, I called my local library and they have both books in their classics section. I’ll collect later today. Your third para certainly appeals:

“In the Kingdom come to America, citizens have both equal votes in elections and equal stakes in the national economy. The Golden Rule is official policy. From cradle to grave, citizens receive an annual credit to draw upon, reflecting an equal share of their nation’s available output of goods and services. All Americans, male and female, have the same opportunities and responsibilities: during the first twenty-one years of life, to become well-educated in the public schools, where every able student obtains at least the equivalent of a college degree, and all are exposed to a wide variety of potential occupations; from twenty-one to forty-five, to serve in the nation’s centrally-planned, regionally-organized industries and professions in a largely self-chosen capacity and location; after forty-five, to devote their extended retirement years to continuing intellectual and spiritual development and volunteer community service. At no time does any citizen work for another or become dependent upon another. All live and work as peers to promote the welfare and prosperity of the nation they share and love.”

“But isn’t a fiscal surplus the norm that governments should aspire to?”

In terms of the “everybody-knows” mythology we use every day, any worthwhile enterprise will turn a profit. By that thinking then, if government is going to be worthwhile, it must create a profit, aka surplus.

You can see this attitude behind the libertarian hatred of government and reluctance to pay taxes. They know, correctly, that the government’s profit is their loss. But they don’t figure out that the government’s loss is their profit. Maybe that is the point where the idea kicks in that a truly democratic government would be their government, and should not be giving their money away.

“But isn’t there also commercial bank lending? A bank lends money to a capitalist, the capitalist pays workers, the worker then purchases Government debt using the money created by the commercial bank.”

As fr as I know, if you articulate the deal a bank makes when it grants a loan, the bank agrees to pay for the borrower’s purchases, the borrower agrees to pay the bank back later. This is true whether the purchase is groceries, or a car, or a house, or bonds.

It’s complicated by modern finance. Eg. if the bank is quick to spin the loan off in a Collateralized Loan Obligation, then investors will supply enough money to pay the vendor, but somebody, the lending bank or investors, or somebody, has to have liquid assets to pay the vendor.

@Sidarth and @Mike Hall many thanks for question posed and explanation. But I’m not so sure of, ‘workers never buy bonds … which are bought and sold, …mostly by banks themselves.’ To the extent that money, excepting cash held by actual people, is exchanged between the private banks, this is true, but aren’t superannuation funds significant bond holders/investors, and thus through them, workers are inveigled into being part of the system?

@Mike Hall

Another related question, where do state owned commercial banks fit in?

In some countries, especially before neoliberal reforms, these banks were given ‘priority lending’ rules where certain sectors like agriculture were provided with very low interest (sometimes 0 interest) loans. Private banks may not like lending because of default risk, but the Government covers any losses arising from such loans.

Excellent post Prof. “The debt issuance does not fund the government deficits.”

“Quantitative Easing” (QE) is exactly the same as a “Reverse Repurchase Agreement”. It swaps a debt (Gilts / Bonds) instruments, back into the cash that bought them originally. No new money is created in the process initially, the quantity of currency units in the non-government sector remains the same.

“Quantitative Tightening” is the same as a “Repurchase Agreement”. It swaps cash into Bonds, thus reducing the cash in the non-government sector and the threat of inflation if households go mad and spend it all. That is, the velocity of circulation of M0/M1 cash and deposits takes off.

The UK Consolidated Fund has finished each year for decades with a deficit. This is made good by the National Loans Fund (NLF). It creates new currency units that add to the units that already exist in the non-government sector.

The NLF never gets paid back nowadays. If the deficit was paid for with government debt, the owners of those Gilts / Bonds, wouldn’t get paid back either.

Have a look at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/653a25abe6c968000daa9b36/Consolidated_Fund_Account_2022-23.pdf You will see the table on document page 7. No payment back to the NLF.

The private banks are licensees/franchisees of a currency issuing government and operate within the bounds of the non-government sector. Bank licences authorise them to create repayable (debt/loan) money (horizontal money) in the currency of the state as distinct from the issuance of net money (vertical money) into the non-government sector by the government spending as monopoly issuer of the currency. Money is a creature of the law as is set out in the Australian Constitution, for example (see ss. 51(xii) & 115).

Private banks don’t take deposits and don’t make loans but that is not the way we have been educated/programmed to understand their operations. A deposit is an at call unsecured loan to a private bank. A “deposit” is no longer the “depositor’s” funds once that step has been taken as it becomes the property of the bank and a portion of the capital of the bank to be held as reserves. Banks “lend” money into existence in exchange for a debt instrument (loan contract) which they purchase from a customer/“borrower”.

Fred,

Commercial banks’ main activity is to grant loans and profit on account of the interest rates spread. Contrary to the orthodoxy, banks don’t need prior reserves in order to lend but instead they first make the loan and afterwards look for reserves, only in case they can’t meet clearing requirements. This is what is meant by banks creating loans out of thin air. Needed reserves are obtained in various ways such as overnight borrowing, selling bonds, or directly borrowing from the CB. The majority of deposits (demand or sight) are created in the loan making process but they are also created when firms and individuals open up deposit accounts in order to facilitate purchases. Finally, deposits are not to be confused with the banks’ capital. By capital in banking we primarily mean equity (tier I) and from the point of view of regulators long-term unsecured bonds issued and sold by bank is also considered capital (tier II).

Money is debt. All money is debt. If you don’t understand that, you don’t understand money. Put more formally, money is a promissory note and as such is documentation of a monetary relationship between two parties: one a creditor and the other of necessity a debtor. Paper notes and reserve deposits at the central bank are liabilities (debts) of the central bank. Treasury securities–just future money, really–are liabilities (debts) of the Treasury. Commercial bank deposits, which constitute the bulk of money in the economy, are liabilities (debts) of the respective bank. Show me money and I’ll show you debt. No debt, no money. It’s that simple.

There are different kinds of money and therefore different kinds of debt. But you can’t have money without debt, and a lot of confusion arises because of trying to distinguish between “money” and “debt”.

My first issue: I am wary of accounts that use infinite regress to explain how private monetary wealth must have come from prior government deficits funded by money creation. There are countries that started out issuing currency by using currency boards (e.g., Singapore) with foreign assets backing them, so currency got into the hands of the public without governments running prior deficits. There are also countries that have run persistent budget surpluses for most of their time (Singapore, Hong Kong, Norway), so again private sector private-held currency wealth could not have all come from prior government deficits.

My second issue: Should the external sector balance be seen as stable, and therefore determining the private and government balances? Bill Mitchell appears to think so for Australia and the US. But why shouldn’t it be as endogenous as the other balances? What about other countries?

Sidharth,

In answer to your question about where state-owned commercial banks fit in, I would suggest they have a vital role if a government takes the well being of its people seriously.

In Australia the Commonwealth Bank filled the role you described, providing competition for privately owned banks, as well as lending long term at relatively low interest to small scale industry and similarly supporting home ownership. The bank guaranteed services right across both regional and urban Australia and also incorporated a separate savings division which was widely supported.

When banking was de-regulated in Australia in the expectation of better services resulting from increased competition, the Commonwealth Bank was eventually privatized to satisfy neo-liberal ideology. One argument for this was that privatization would save the government having to put more capital into the bank to allow it to compete with the new private banks. (The usual fiscal deficit fiction.)

However, without a public bank to set standards the major banks that emerged following de-regulation have been free to gouge profits, abuse customers and withdraw services. Collusion rather than competition has been the norm, and the privatized Commonwealth Bank with its large inherited market share has arguably been the worst offender.

The poor behaviour by banks is partly due to inadequate and inept regulatory authorities. For example, the Hayne Royal Commission into bank misbehaviour received more than 10,000 complaints from victims of financial abuse. Six years later, less than 1% have received financial redress from the banks.

If publicly owned commercial banks serve public purpose as determined by our elected representatives, and can always be guaranteed by a currency issuing government, why do we tolerate barely regulated, privately owned banks whose primary purpose is to transfer as much wealth as possible from clients to shareholders?

Newton,

Not the easiest narrative to read, but Equality was an improvement. He certainly made an impression on many writers and academics – and was indeed prescient. I didn’t realise it related to Bellamy at the time, but I enjoyed Frank Moone’s take on Looking Backward when it was published a couple of years ago.

https://medium.com/illumination/looking-backward-b685cea1e034

Kind regards.

@Creigh Gordon: “All money is debt”.

Except, ideally, *public sector money*?

Obviously a currency-issuing government can purchase – debt-free to itself – resources which the government needs to implement those public services wanted by the electorate, assuming the needed resources are in fact available for purchase by the government.

That’s the mesage we need the public to understand.

Glad you got something from Bellamy, Mark. Few today would be willing to engage with Victorian novels, however prescient. Virtually everything around us now is deconstruction at best, defeatism at worst. If I could, I would do the opposite of Julian West and return, in a heartbeat, to the mid-20th Century. Problems and imperfections abounded, of course, but so did an invigorating sense of possibility, that a better, more beautiful world was within our grasp.

@Jason

Couldn’t foreign currency inflows be seen as allowing the domestic private sector to have more money in domestic currency than they would’ve otherwise?

If the two sources of widely accepted money are the Government and the commercial banks, the only way for foreigners to exchange their currencies for local currencies would be using the money already issued by the Government or the banks.

Neil Halliday, take a look at the central bank (e.g. the Federal Reserve Bank) balance sheet. You’ll find outstanding central bank notes and reserve deposits listed on the liability side, It’s true that public debt and private debt have different consequences, but they are both debt.

Creigh writes:

” It’s true that public debt and private debt have different consequences, but they are both debt.”

Not only different consequences, but also different origins, which is the bit the public doesn’t understand. Treasury can fund government services (if the needed resources are available for purchse), with (national) money created out of thin air. To whom is this ‘debt’ owing?

btw, central banks raising interest rates amounts to stealing money from those who have no savings, as well as those with mortgages – and gives money to people with savings and no mortgage. – a sick, dysfunctional system; hence the CB and the treasurer blaming one-another for the slowing economy\ and cost of living crises.

@Jason

“There are countries that started out issuing currency by using currency boards (e.g., Singapore) with foreign assets backing them, so currency got into the hands of the public without governments running prior deficits. ”

But did the Singaporean govt issue their own currency?

I want to know if a bank debt is payed say in full, does the money (principal) gets destroyed? If yes, how does that happen from the banks point of view?

Hi Bill,

What about the risk of money debasement ? for instance if the US continue to grow its fiscal deficit, could the USD ultimately continue to debase vs other currencies of low fiscal deficit countries such as Switzerland ? then could nt it lead to a continuous need to increase US deficit as spending power decrease for the private sector ?…

@Antoine

You mean the exchange rate depreciating to infinity? Bill has talked about that previously

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=40035