These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Latest scientific research points to long COVID in Australia being a significant and growing problem

I have been regularly following the scientific literature on the labour market impacts of COVID-19 and as the evidence is becoming richer we are getting a clearer idea of those impacts. The short conclusion is that public health policy makers, under pressure from ill-informed individual and corporate interests, have failed dramatically to protect the public health and there will be long-term economic consequences as a result, quite apart from the devastating personal costs. It is a very strange phenomenon that we have observed over the last several years now. One that required strong public health leadership but which has, instead, been marked by a curious cloud of denial and abandonment. We are all to blame for that abandonment. The latest evidence indicates that long COVID in Australia is a significant and growing problem that is not only undermining the well-being of the people involved but is also a major restraint of economic performance.

Today (August 19, 2024), the Medical Journal of Australia published a scientific modelling study – The public health and economic burden of long COVID in Australia, 2022–24: a modelling study – which estimates of:

… the number of people in Australia with long COVID by age group, and the associated medium term productivity and economic losses. number of people in Australia with long COVID by age group, and the associated medium term productivity and economic losses.

The motivation for the study is clear:

Evidence is accumulating that the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has effects on several organ systems, beyond causing acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19).

While there is some ambiguity as to what constitutes ‘long COVID’ the now accepted categorisation “refers to symptoms that develop during or after the acute infection, reflecting respiratory, cardiac, neurocognitive, immunological, and other organ system dysfunctions”.

There are many factors that influence the variation in estimates – including the “duration of persistence” of the “reported symptoms”, the “severity of the acute infection”, the variant involved, “vaccination status”, “other medical conditions” and demographic data (age etc).

The evidence is clear though that long COVID can still be a problem even for those with “mild or asymptomatic” COVID infections as well as for those people who succumb to multiple infections over time (even if they are mild).

The evidence also shows that:

COVID‐19 vaccines protect against long COVID, and the prevalence of long COVID is higher among unvaccinated than vaccinated people.

The researchers argue that the public health response was largely focused on minimising hospitalisations rather than dealing with long-term COVID consequences.

The likely impacts on the labour market – reduced participation, lower productivity etc – was overwhelmingly ignored by the health authorities including the World Health Organisation, which has gone weak at the knees on the issue.

Reasearchers are also noting that as the public health authorities have not required on-going testing their capacity to reveal the true nature of these impacts is compromised.

They have to resort to alternative methodologies – that is, modelling studies based on “seriological surveys”.

I won’t detail the research methodology and techniques much because it is the results that have broad appeal and those interested can consult the study which is offered on open access by the journal.

Essentially they used what is called a “susceptible–exposed–infected–recovered (SEIR) model”, which is in the class of – Compartmental models in epidemiology – that are used to create mathematical models of infectious diseases.

They thus used a standard approach and the seriological data was generated from “blood donors” spanning the ages of 18 to 84 years of age (median age 44-47) collected over 4 time periods between January 2022 to December 2023.

They then used the samples to construct extrapolations between the discrete data collection periods.

They also used blood samples from a 0-19 years cohort from hospital data but only had one time period observation.

Assumptions were made to extend that data to match the four time periods collected for the adults.

The working definition of long COVID was that used by the WHO:

… the continuation or development of new symptoms three months after the initial SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least two months with no other explanation.

The “proportions of people with long COVID symptoms (prevalence rates)” was summarised by this Table (this is the high estimate section) or the worst-case scenario.

So their estimates are quite alarming.

Their next task was to estimate:

… the productivity loss associated with long COVID using a labour supply approach. Productivity loss comprises both the reduction in the contribution of labour to gross domestic product (GDP) and the reduction in the contributions of non‐labour production factors that are influenced by labour supply.

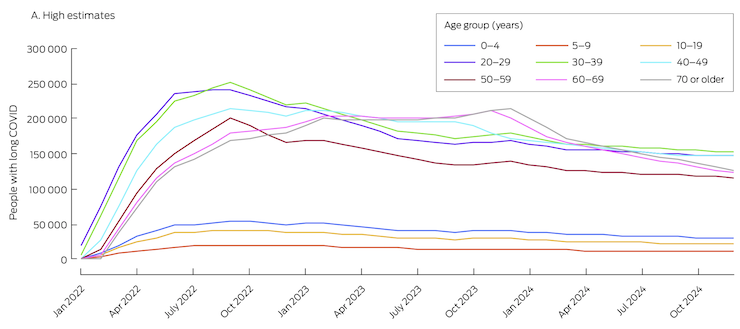

The study produced this time profile for people with long COVID by age group:

Thus, in September 2022, there were around 1.3 million Australians (total population = 26.9 million) enduring long COVID spread across the age range.

In terms of working hours lost because people with long COVID were either unable to continue working or had to reduce the hours they worked, the researchers estimated the

… mean labour loss attributable to long COVID in 2022 was projected to be 102.4 million … hours – 0.48% … of total worked hours in the 2020–21 financial year … The estimated mean labour loss was greatest for people aged 30–39 years: 27.5 million … (26.9% of total labour loss) … The second greatest loss was for people aged 40–49 years: 24.5 million … (23.9% of total labour loss) …

In terms of GDP loss as a result of the shorter working hours, the study found that:

The estimated mean GDP loss attributable to long COVID in 2022 caused by the projected decline in labour supply alone (2020–21 value) was $4.8 billion … or 0.2% of GDP. The estimated mean GDP loss caused by the projected decline in labour supply and reduced use of other production factors was $9.6 billion … or 0.5% of GDP

Which in scale terms was about one quarter’s GDP for that year.

The researchers note that their lost output measures are understatements of the likely losses because they didn’t take into account third-parties:

… who cannot work because they are caring for non-employees … ill people requiring isolation, or other employees affected by COVID-19 or long COVID.

Other factors that make their estimates conservative were also identified.

The public health authorities did not consider any of these impacts in its decisions regarding health measures (masks, vaccines, etc).

And the researchers emphasise that the authorities should focus on “preventing and treating acute COVID-19”, including:

… regular access to vaccine boosters and antiviral medications for all working adults, accessible testing, promoting mask wearing during epidemic waves, optimising indoor air quality by improving ventilation, and encouraging the use of high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters.

The reality is that the authorities have dropped the ball on most of these simple measures.

Even the access to antiviral medication is highly restricted in Australia, despite the evidence showing it reduces the “risk of long COVID”.

One of the considerations that the policy makers claim shapes their policy response is cost – the dollars they don’t want to spend – for fear of running out money!

This is a classic example of how ignorance about the capacity of the currency issuer leads to poor policy design and execution.

And, the researchers noted that “the cost of long COVID was much greater than putting in place better frameworks” (Source).

And the problem is getting worse.

Conclusion

As time passes we get more solid research evidence as to the devastating impacts of COVID, yet policy makers are in denial.

The rest of the population also seems to be totally uneducated as to the consequences for the long term health of the community.

It is hard to understand this apathy.

Anyway, I have my mask at the ready when in risky situations, will soon get my 8th vaccine shot since 2020, and regularly use an air purifier.

The science and data suggests that is not a bad personal strategy, which could be amplified if the public authorities took the problem seriously.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“COVID‐19 vaccines protect against long COVID, and the prevalence of long COVID is higher among unvaccinated than vaccinated people.”

The study reports:

“COVID‐19 vaccines protect against long COVID, and the prevalence of long COVID is higher among unvaccinated than vaccinated people. An Italian study found that 41.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37.0–46.7%) of unvaccinated health care workers had developed long COVID, 30.0% (95% CI, 6.7–65.2%) of those who had received one vaccine dose, 17.4% (95% CI, 7.8–31.4%) of those who had received two doses, and 16.0% (95% CI, 11.8–21.0%) of those who had received three doses.11 COVID‐19 vaccines may also reduce the severity of long COVID and improve the quality of life of people with the disorder.“

I would certainly consider the methodology and scope in making the above determination. For the vaccinated; did LC develop after vaccination or from infection? What interval between vaccination and infection?

It’s very early days in this pandemic disease to make any unequivocal opinions on the effectiveness and long term safety of a new delivery platform (mRNA) for the treatment of a novel virus, which is still undergoing rapid mutational development. Despite early claims, it doesn’t prevent infection nor does it prevent replication after infection. And it’s worth remembering that all other vaccine trials for coronavirus genus – MERS & SARS – were unsuccessful mostly because of antibody dependent enhancement (ADE) after challenge.

That aside, isn’t it a ‘good’ thing that productivity is falling if economic degrowth is desirable? Isn’t it perhaps a blessing that more of us are unwell and may very well experience a shorter life expectancy especially with the catastrophic impacts from human (8.3billion) related activity? When the oil stops flowing in a few years time, the human endeavour will return to a pre-industrial population as the FF bounty ends – and if we continue on the same socio-economic road, the standard of living may be well below that of our great, great grandparents, where survival rather than productiveness is the most important consideration.

The long-term effects of Covid, I suspect, will go far beyond the health of individuals and the economy. The greatest damage will be to public confidence in expert opinion in many areas of scientific endeavor. If top-tier experts could be so wrong, so conflicting, so scornful of opposing views, then perhaps it’s time to reconsider the so-called scientific consensus on a wide variety of issues from global warming to gender fluidity–indeed, to materialist reductionism itself.

@Newton Finn re: ‘if top-tier experts could be so wrong.’ But they haven’t been proved to be so very wrong about the new and fast moving covid virus have they, and there is even less of a scientific consensus breakdown on global warming, The damage comes primarily from mixing with politicians and the commentariat. We might note a difference from expert economists who maintain their consensus despite real world evidence because of their underlying ideological bias shared with politicians.

Bill said the following: ‘and regularly use an air purifier’

Great advice, an air purifier that use ultra-violet light (UV) does the following

‘A UV light installed in an air conditioning (AC) system serves two main purposes: Air sanitization: UV-C light can kill airborne microorganisms like bacteria, viruses, and mold spores as the air circulates through the HVAC system. This helps improve indoor air quality by reducing the number of harmful contaminants in the air.’

The federal government should be making it mandatory for all Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems to have UV-C filters especially in international aircraft (for obvious reasons)

Corporate media are now trying to hide or play-down the evidence that Mpox (monkey pox) can be transmitted via the air, read the following article regarding the scientific evidence of the Mpox virus staying in the air for 90 hours.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/08/mpox-monkeypox-round-up-history-wastewater-r0-and-is-it-airborne-yes.html

Due to the Washington consensus (Neo-liberalism) people in west and central Africa have to eat bush meat to survive, mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a viral zoonotic disease. Zoonotic means the virus passes from animals to humans.

Africa is intentionally kept poverty stricken by the US empire for the sake of cheap resource extraction by multinational corporations. The US empire have the power of veto over the world bank and the IMF.

I think it’s worth pointing out that ‘Long COVID’ is not a disorder isolated to COVID – for example, there is evidence that any infection can cause Chronic Fatigue, the biggest example probably being influenza.

Heck, I know personally know someone who has ‘Long tick bite’ CFS.

Long COVID certainly gets all the attention, but I would wager that Long Influenza would have a similar effect on the economy, allowing for differences in infection levels. I would certainly be interested in a comparison.