The US is now a rogue state. One example is the conduct of the US…

ECB estimates suggest meeting current challenges will be impossible within fiscal rule space

In the recent issue of the ECB Economic Bulletin (issue 4/2024) there was an article – Longer-term challenges for fiscal policy in the euro area – which demonstrates why the common currency and its bevy of fiscal rules and restrictions is incapable of meeting the challenges that humanity and the natural world face in the coming years. The ECB article is very interesting because it pretty clearly articulates the important challenges facing the Member States and provides some rough estimates of what the fiscal implications will be if governments are to move quickly to deal with the threats posed. However, it is clear from the analysis and my own calculations that significant austerity will be required in areas of expenditure not related to these challenges. Given the current political environment in Europe, it is hard to see how such austerity can be imposed and maintained in areas that impact the daily lives of families. What is demonstrated is that the architecture of the EMU is ill-equipped to deal with the problems that Member States now face. The common currency and fiscal rules were never a good idea. But as the challenges mount it is obvious that Europe will have to change its monetary system approach in order to survive.

I will comment further on the UK and French elections held in the last week or so when there is more data available.

The UK result is not what it seems – how can a system where the party that gets 33.8 per cent of the vote yet gains 63.2 per cent of the seats be sensible, especially with a turnout of only 59.8 per cent, the lowest since 2001 and the second lowest since 1918?

The Tories gained 23.7 per cent of the vote yet only won 18.6 per cent of the seats, while the Reform UK won 14.3 per cent of the vote to gain 0.8 per cent of the seats.

If we consider the Farage gang and the Tories to really be part of the same vote then it is clear in many constituencies Labour’s success does not reflect the political sentiment of the voters.

Add to that the fact that Labour’s vote actually fell (9.69 million votes compared to 10.27 million in 2019).

So this is hardly a great victory for the way Starmer has moved the Labour Party.

Significant was their attempts to destroy the career of Jeremy Corbyn in Islington North failed – which I was really happy about.

The victory of the Left coalition in the French election also suggests that Starmer’s purge of the Left in Britain was flawed.

Anyway, more on this topic when the detailed constituency data is available later this week.

Now, let’s return to the focus on the Eurozone and its so-called fiscal challenges.

The challenges identified are not specific to Europe, given that many countries (particularly in the advanced bracket) in one way or another are facing these problems.

The ECB identifies these as the “most important challenges” facing authorities in the current period:

… demographic ageing … the end of the ‘peace dividend’ … digitalisation … and climate change …

Their conjecture is that dealing with these challenges will impose massive stress on the fiscal capacities of the Member States.

First, like many places, the European nations are “witnessing a significant decline in fertility rates, coupled with steady increases in life expectancy, resulting in an ageing population.”

What is the problem?

The general problem facing societies with ageing populations is that the dependency ratio is rising, which means that there are less people of productive age relative to those who have retired and depend on the smaller group for on-going material well-being.

The opposite problem is experienced in many African nations – they have high dependency ratios because their birth rates are high and children below working age make up higher proportions of their total population than in more advanced nations.

The usual construction of the ageing society issue is that it strains public finances because deficits are likely higher to provide pension and health care support for a growing cohort.

The ECB analysis is no exception:

This demographic ageing presents challenges for government finances. With the number of elderly citizens increasing relative to the working-age population, pay‑as-you-go pension systems face mounting financial pressures. Furthermore, ageing populations typically require more extensive healthcare services and long‑term care.

Adopting this construction then leads to all sorts of dead-end discussions about extending working lives before pension entitlements and forcing private health insurance schemes onto people.

The ECB article reports complex modelling of risk scenarios about the ageing society with commensurate estimates of the “increase in the public cost of pensions” and concludes that:

The increased burden of ageing will require policy reforms or structurally increased savings in other areas.

This is the mainstream angle on the rising age dependency ratios in Europe and elsewhere.

However, this construction usually leads to policy recommendations that actually make the problem worse if applied.

The ageing problem for society is not a fiscal problem.

Rather it is a productivity problem.

The future generation of workers will have to be more productive in material terms than their parents if material living standards are to be maintained.

And that, in turn, also requires available resources.

A nation can always provide first-class health care if there are well-trained and effective health care professional staff interacting with modern equipment.

Government which have been worrying about this situation and constructing it as a fiscal dilemma implement policies that cut funding to areas that are necessary to nurture to ensure future productivity growth and technological innovation.

Look at the mess that British NHS is in, as an example.

And the way governments have cut spending growth in education and training areas over the last several decades is directly related to the decline in productivity growth exhibited by many nations over the same time period.

Now, the situation is somewhat different in the EMU because the individual Member State governments are not only constrained by real resource availability but also by financial capacity, given they surrendered their currency sovereignty in favour of adopting a foreign currency – the euro.

While the Australian government, for example, can always ‘afford’ (financially) to provide first-class health care, for example, as long as it has productive resources that are suitable to bring into use.

But a Eurozone government cannot as easily ensure such outcomes unless the ECB, itself, continues to act as a fiscal agent with the union.

However, that ‘unless’ is mired in conditionality, fiscal rules, bloody-mindedness, politics, and other dysfunctions, which makes for the whole mess that Europe finds itself in.

The European authorities address the ageing society issue as a fiscal threat, whereas they should really be seeing it as a dimension of their own failure to design a functional monetary union.

The ageing society is just one example that demonstrates the unviability of the common currency.

Second, the ECB claims that governments will have to incur the “Fiscal costs” arising from “the end of the ‘peace dividend'”.

What does that mean?

Essentially every nation is ‘gearing up’ their military capacities because of some (non-existent) threat that Russia might head West – well further west than the Eastern regions of the Ukraine.

The ECB argues that when the “cold war thawed” there was a “peace dividend” which meant that:

… governments refocused their budgets, targeting new priorities such as increased social welfare spending.

Now, they are in full-scale mobilisation.

As an aside, I am regularly reading statements from European leaders that suggest they see a war as inevitable.

It is a madness but that is the way they are pointing with their decisions and threats.

While the extra spending will boost growth in nations that produce and export weapons etc and probably “R&D-intensive investment” it will push nations to the inflation barrier, in the same way it did in the late 1960s when the US was spending big to fight the Vietnam conflict.

The other problem for Europe is that it will probably push government finances into breach of the fiscal rules and then the Commission will demand cuts to things that actually help people live their lives rather than kill others.

Third, the ECB identifies the “Fiscal costs of closing the digitalisation gap” will challenge Member State governments.

As a result of years of austerity following the creation of the monetary union, it is now clear, that like other infrastructure, Europe has significantly underinvested in “digital infrastructure and digital public services in order to maintain competitiveness”.

The Commission’s own research suggests that the EU is behind nations such as the US and China in this context to the tune of “around 0.9% of the EU’s GDP” – which is massive.

The EU has a habit of creating fancy-named programs – such as the “Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030” which is “a set of targets and objectives aimed at catching up in the area of digital transformation, supported by public investment”.

Yet, they also usually underinvest in these programs.

To meet the Programme targets, massive increases in public funding will be required and my preliminary calculations suggest (when put together with the other challenges) that the desired spending outcomes will bust the fiscal rule thresholds by some margin.

So how is that going to work?

The political shifts in Europe at present clearly demonstrate that the mainstream approach is not being supported by the voters.

Within all the current uncertainty of the French outcome, the one glaringly obvious result is that the French people have rejected the Macron-way.

That suggests that attempting to fit the extra spending required to meet these challenges within the fiscal rule envelope by cutting other areas such as welfare, education, health care, employment support etc, will not work.

Finally, the ECB identify “Fiscal effects of climate change” as being a major challenge facing the Member States as it does all governments.

There are several dimensions to this:

… from the direct costs of extreme weather events to the broader economic implications of transitioning to a low-carbon future …

The nature of these challenges are such that immediate spending is required.

For Europe, which is facing a problem of desertification across its agricultural food bowl, there is no time to delay.

The ECB recognises this:

For example, the European Commission’s PESETA IV project estimates that welfare losses from climate change in southern Europe will be several times larger than in the north of Europe, mostly because of higher temperatures and water scarcity.

Yes, the EU has a ‘plan’ – of course it does – it has a plan for everything – except how to function properly!

All governments are confronting the costs of “extreme weather events”, “disaster relief”, etc.

I was talking with an expert recently who predicted that the Australian construction industry will soon face major shortages of timber as the plantation forests get increasingly hit with major bush fires.

The industry requires stable, long-term growing conditions, yet the climate events are coming much more frequently.

The major fires in 2021 caused huge increases in the cost of house building in Australia as a result of the destruction of the forests in Victoria and NSW.

All governments are going to have to make massive outlays in spending and increase their relative size in the economy to meet the climate challenge.

Existing housing will need to be re-engineered to increase energy efficiency.

New energy efficient housing will be unaffordable to low-income families and will require governments pay the difference between that level of housing and the existing rubbish that is built by private developers.

Europe will face a particular challenge given the ageing housing stock in many nations.

The IMF has claimed that spending will have to increase by “around 0.4 percentage points of GDP over the next few decades as a result of a policy package designed to achieve net-zero emissions in 2050.”

That is an underestimate in my view.

It also ignores that fact that economic growth itself will have to decline on average which under current policy parameters will mean governments will face an erosion of “government revenues and result in higher debt servicing costs” if the mainstream paradigm that deals with public finances persists.

When I say “have to” – that is a degrowth perspective.

Climate change itself is likely to undermine GDP growth anyway, with the same effect on Member State tax capacity.

The ECB estimate that this effect alone will increase deficits and add to public debt.

Have you had your pen and pencil out and adding all these impositions on the Member State fiscal outcomes together?

The ECB article does attempt to estimate the “possible fiscal burden arising from the developments described in the previous sections”.

Well I can tell you that the fiscal rules in place, and which are now being enforced again, will not be met if the European governments actually start doing something to meet these challenges.

On average they estimate that the “euro area governments” would require primary fiscal surpluses to increase by “2% of GDP” to meet the 60 per cent debt rule.

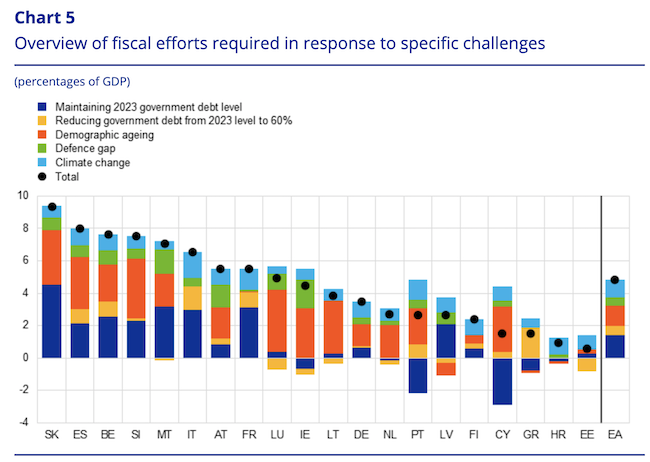

This chart shows the fiscal adjustments required.

You can see for some nations the estimated shift required is beyond belief – in the ECB’s words “the necessary fiscal adjustment is large by historical standards”.

They also suggest the scale of required adjustment could increase in the ‘medium term’ – for example, they use very conservative assumptions with respect to global warming in their simulations.

Conclusion

While the ECB paper does not exactly state the obvious the meaning is clear – even to get within a ballpark of what is required will require substantial austerity being imposed on areas of expenditure not related to these challenges.

My prediction: an on-going mess and the challenges will not be met adequately.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Season 2 of our manga series – The Smith Family and its Adventures with Money – begins July 12, 2024

Yes, we are pleased to announce that the – MMTed – Manga series will return for Season 2 this Friday, July 12, 2024.

There will be some new surprises, some turnarounds, crises, personal epiphanies, some loud music and more in Season 2.

In Season 1, we focused on the dynamics of the immediate Smith Family – Elizabeth, Ryan, Kevin and Emma – with some interaction from their friends.

In Season 2, the focus is on the school kids and their interactions with their new economics teacher Ms Allday.

Professor Raul Noitawl returns with his relentless analysis on the morning finance TV show but the real world events start testing the patience of his most loyal viewers.

Episode 1 begins with economic strife hitting the community.

Join us for Season 2, fortnightly from this Friday.

Thanks as usual to Mihana, my partner in ‘crime’ or should I say in art – her drawings are as usual magnificent. She also designed the cover of our new book (as above).

Thanks also to Mitch who helps with the translation.

New Book – now being posted out from the publisher

Our new book – Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure – is now being posted out to all those who have already ordered it.

It will be officially launched next week at the – UK MMT Conference – in Leeds (July 16, 2024).

As of today, it was #6 Amazon’s – Hot New Releases in Macroeconomics – so thanks to all who have ordered it so far.

We released a short promotional video last week to give people some idea of what it is about.

You can find more information about the book from the publishers page – HERE.

It is available through the publisher and also from all the major book sellers.

We hope you enjoy it.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Re. the UK, votes (14.3%) for Farage and his xenophobes did indeed cost the Tories many seats, rather than Labour winning them. Would these voters in the main have voted Tory in the absence of Farage, or would they in the main have swelled the ranks of the 40% who felt so unrepresented as to not vote at all? Starmer’s Labour have decided to rule off the back of a pissed-off electorate rather than an inspired one. A far far cry from 1945 and a 72.8% turnout.

Corbyn secured 49.2% of the vote in his constituency this time around. Starmer’s support was 48.9%. Good to see Diane Abbot retain her seat but that was never in doubt.

Can the Party membership hold Starmer to account? Angela Rayner was acting on their behalf when she intervened over Abbot.

@Matthew T Hoare Ah I see, Corbyn got in easily, securing 49.03% of the vote compared with 34% for Labour HQ’s candidate, while Starmer was elected with 48.9% of the vote in his Holborn and St Pancras constituency, with the only marginally significant chalenge coming from an independent anti-Starmer-Gaza war candidate, with nearly 19%. A bit more telling is that the turn-out in Corbyn’s constituency was 67.5%, whereas in Starmer’s it was 54.46%. Only a minority of Starmer’s constituents can summon any enthusiasm for him.

Yes good that Diane Abbott got elected again though it was a walkover in her constituency, with only 53% bothering to vote and the Green Party beating the Conservative’s candidate – even many in the Orthodox Jewish community didn’t think it worth bothering to vote for their Conservative. Labour HQ deigned to allow Abbott to stand for Labour only because they knew they had no chance of defeating her if she, like Corbyn, ran as an independent. Unfortunately I rather think that Starmer and his follower MPs and Labour HQ have seen off the Labour membership. The enthusiasm and increase in Labour membership that accompanied Corbyn in trying to make it into a progressive party has been drained or expelled.

Fiscal action should focus on penalizing energy consumption by the consumer-polluter, rather than on building sources of “clean” energy. Increased spending on the “green” energy transition is but a disguised wealth transfer scheme. Such spending has not, and will not, result in reduced total emissions.