Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australian low-paid workers get a 3.75 per cent nominal wage increase but are still worse off in real terms

On June 4, 2024, Australia’s minimum wage setting authority – the Fair Work Commission (FWC) issued their decision in the – Annual Wage Review 2023-24 – which provides for wage increases for the lowest-paid workers – around 0.7 per cent of employees (around 79.2 thousand) in Australia. In turn, around 20.7 per cent of all employees, who are on the lowest tier of their pay award (grade) receive a flow-on effect. The FWC “decided to increase the National Minimum Wage and all modern award minimum wage rates by 3.75 per cent, effective from 1 July 2024”. The decision reflected concerns for “cost-of-living pressures” being particularly endured by “those who are low paid and live in low-income households”. However, the decision, which was vehemently opposed by the employers, still leaves the lowest paid workers worse off in real terms compared to where they were at the onset of the pandemic. We should have done better than that.

In this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017) – I outlined:

1. Progressive minimum wage setting principles.

2. The way staggered wage decisions (annually) lead to falling real wages in between the wage adjustment points.

I won’t repeat that analysis here. But it is essential background to understanding why the decisions taken by Fair Work Australia have been inadequate for a long time.

Who is affected?

The FWC notes that:

The Australian government had “estimated that 0.7 per cent of the Australian employee workforce is reliant on the NMW — that is, the NMW sets their actual rate of pay — and thus would be directly affected by any adjustment made to the NMW. This estimate was taken from a submission made by the Australian Government that approximately 79,200 employees are NMW-reliant … However, we consider that this estimate now requires significant downward

revision …The upshot of this is that the NMW has very limited practical effect in the Australian industrial relations landscape notwithstanding its role in the statutory annual wage review scheme.

The FWC, however, notes that:

Approximately 20.7 per cent of the Australian workforce, or about 2.6 million employees, are paid in accordance with minimum wage rates in modern awards. They, and their employers, are directly affected by this decision.

What this means is that a small number of workers actually get the National Mininum Wage (NMW) but a much larger number (the 2.6 million or 20.7 per cent of total workforce) are paid at minimum levels on so-called ‘modern award’ arrangements, which apply in each sector.

There are 121 modern awards in the industrial structure.

The practice is that when the NMW is changed, that decision then flows directly into these minimum levels for the modern awards.

The FWC notes that:

The characteristics of employees who rely on modern award minimum wage rates and are therefore directly affected by our decision are significantly different to the workforce as a whole. They mostly work part-time hours, are predominantly women, and almost half are casual employees. They are also much more likely to be low paid.

Which means the decision directly improves the outcomes for these low-paid workers but “the broader economic effective of the Annual Wage Review decisions is limited. The total wages cost of the modern-award-reliant workforce constitutes less than 11 per cent of the national ‘wage bill”.

Which then should discourage anyone from believing the employer organisations that have conniptions when the FWC provides some wage relief for the very low paid workers in Australia.

Their claims reflect their own greed and willingness to exploit the most vulnerable workers rather than being based on any economic analysis.

Further, last year, the then RBA governor tried to use the FWC decision to demonstrate his narrative that there were dangerous wage pressures building up in Australia, which justified the on-going interest rate hikes.

Trying to suggest that the minimum wage decision would be inflationary was always an act of desperation from the Governor.

He was not reappointed in his role.

The new governor claimed yesterday that there would be no inflationary impact from the latest RBA decision.

Funny how a year completely changes the conclusions.

The FWC also made it clear that:

Despite the increase of 5.75 per cent to modern award minimum wage rates in the AWR 2023 decision, the position remains that real wages for modern award-reliant employees are lower than they were five years ago. This has undoubtedly placed financial stress upon such employees who, as earlier explained, are disproportionately casual, part-time, low paid and female and are therefore most vulnerable to adverse changes in economic circumstances.

Where the parties stand

The FWC received bids (submissions) from various parties in the process of making its decision – the ACTU (peak union body), government, various employer groups.

The Australian Chamber Commerce and Industry (ACCI), which represents around 400,000 employers demanded the FWC limit the increase to 2 per cent.

The FWC responded:

This proposal would result in a further significant real wage cut for modern award-reliant employees in circumstances where such employees are already subject to financial stress for the reasons earlier explained.

ACCI claimed “all parts of the economy must play their role” in reducing the inflationary pressures but that didn’t rub with the FWC who responded by noting that:

The principal difficulty with this proposition is that it would require modern award-reliant employees, who are by definition the lowest-paid group of employees in each industry sector or occupation in which they are employed, to be required to take a real wage cut over the forthcoming year. By contrast, it is forecast that wages growth in aggregate will exceed inflation over the next 12 months.

The FWC could have also noted the extensive price gouging that is now clearly evident among many of its own members who are doing nothing to ‘play their part’.

The other large employer group, Ai Group, demanded a wage increase of less than 3 per cent, was also rejected for the same reasons as noted above.

The ACTU wanted a 5 per cent rise, but that was rejected because while the FWC said “We do not consider that there is a sound basis at this time to award wage increases that are significantly above the CPI”.

Well it depends on the perspective.

The current inflation rate is much lower than it was when the NMW was last adjusted 12 months ago.

Between the nominal adjustments, however, there has been significant real purchasing power erosion, which could have been reduced by an above the CPI increase now.

While the Federal government supported a specific wage increase last year (a 7 per cent increase) which they said “would preserve the level of their real wages” for the lowest wage workers, this year, they went soft (as usual) and did not specify a quantum only to say they wanted to ensure that “the real wages of low-paid workers do not go backwards.”

The Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) Decision

In its 2024 decision – Fair Work Australia wrote:

We have decided to increase the National Minimum Wage and all modern award minimum wage rates by 3.75 per cent, effective from 1 July 2024 …

In determining this level of increase, a primary consideration has been the cost-of-living pressures that modern-award-reliant employees, particularly those who are low paid and live in low-income households, continue to experience notwithstanding that inflation is considerably lower than it was at the time of last year’s Review. Modern award minimum wages remain, in real terms, lower than they were five years ago, notwithstanding last year’s increase of 5.75 per cent, and employee households reliant on award wages are undergoing financial stress as a result. This has militated against this Review resulting in any further reduction in real award wage rates. At the same time, we consider that it is not appropriate at this time to increase award wages by any amount significantly above the inflation rate, principally because labour productivity is no higher than it was four years ago and productivity growth has only recently returned to positive territory …

The increase of 3.75 per cent which we have determined is broadly in line with forecast wages growth across the economy in 2024 and will make only a modest contribution to the total amount of wages growth in 2024. We consider therefore that this increase is consistent with the forecast return of the inflation rate to below 3 per cent in 2025.

Staggered adjustments in the real world

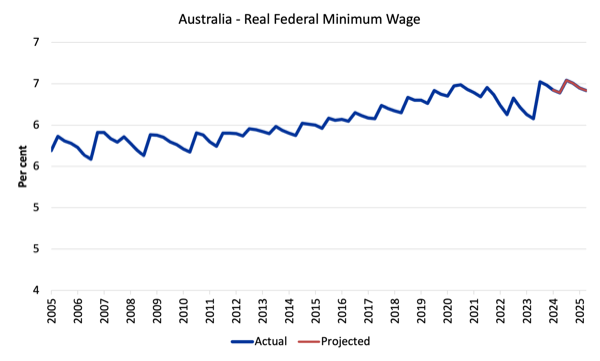

The following graph shows the evolution of the real purchasing power of the NMW since 2005.

We have extrapolated the current decision, which applies from July 1, 2024, over the next 12 months (until the next decision) using RBA inflation forecasts to deflate the nominal NMW.

The familar saw-tooth pattern is clear.

I explained this pattern in detail in this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017).

Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the Fair Work Commission so that at the time of the nominal adjustment (July 1 each year) the real NMW usually rises somewhat (perhaps not back to where it was 12 months earlier).

Each period that the curve heads downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded.

That is, in between the decision periods, the inflation is on-going and erodes the nominal NMW.

That is one problem with these discrete adjustments and I would much rather the FWC built into the system, a feature that is common on most multi-period bargains, escalation.

That is, they could easily index wages to the quarterly inflation rate which would better protect real wages.

You can gauge the annual growth in the real wage by comparing successive peaks.

The decisions since 2012 have provided for some modest real income retention by these workers although it depends on how inflation is measured.

You can also see the troughs became shallower between 2012 and 2016 than in the past because the inflation rate moderated as a result of the GFC and the austerity since that has kept economic activity at moderate levels.

In more recent years the peak-trough amplitude has risen again and the FMW adjustments have failed to redress the purchasing power erosion to the nominal FMW even though each adjustment provides some immediate real wage gain for workers, those gains are ephemeral and the inflation process systematically cuts the purchasing power of the FMW significantly by the time the next decision is due – these are permanent losses.

Last year’s decision meant the purchasing power of the FMW returned to a level not seen since 2020.

The current decision almost holds that line.

The other issue is that in the 12 months ahead, there is modest real wage erosion compared to the real NMW at the end of 2023.

The other problem relates to the appropriate measure of inflation.

I discuss that issue in detail in this blog post – Real wage cuts continue in Australia as profit share rises (May 15, 2024).

In a nutshell, the FWC uses the CPI as the measure.

However, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recognise that there was a “need to develop a measure of ‘the price change of goods and services and its effect on living expenses of selected household types” and they now publish their so-called Selected Living Cost Indexes (SLCIs), which use expenditure patterns of different cohorts in society (as weights in the index) to assess the “the extent to which the impact of price change varies across different groups of households in the Australian population”.

One of their SCLI is the Employee Households index.

In the March-quarter 2024, for example, the annual growth in the CPI was 3.6 per cent, while for the Employee SCLI it was 6.5 per cent.

Over the recent inflationary episode the SCLI has been well above the CPI in growth terms.

What this means is that recent nominal wage adjustments designed to preserve real purchasing power that use the CPI as the inflation measure will seriously understate the real wage erosion.

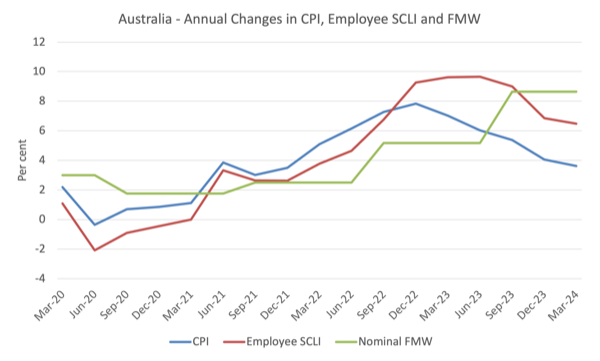

The following graph shows the problem – it shows the annual movements in the CPI, Employee SCLI and the nominal FMW since the March-quarter 2020.

When the FMW is above the other lines then the real purchasing power of the minimum wage is rising and vice versa.

You can see that since the December-quarter 2021, the real erosion in the nominal FMW has been significant up until last year’s FMW decision.

But the erosion was greater in the period between the September-quarter 2022 and the September-quarter 2023 if we use the Employee SCLI.

And last year’s rather large FMW increase which provided some real wage gains if we use the CPI only just caught up with the cost-of-living rises as measured by the Employee SCLI.

And we compared the real FMW at the start of the pandemic with its current value using the Employee SCLI as the deflator then we would see it was lower by around 2 per cent.

Lowest-paid workers improve relative to other workers but all workers still fail to share in productivity growth

Another perspective is to compare the movement in the Federal Minimum Wage with growth in GDP per hour worked (which is taken from the National Accounts).

GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity and tells us about the contribution by workers to production.

Labour productivity growth provides the scope for non-inflationary real wages growth and historically workers have been able to enjoy rising material standards of living because the wage tribunals have awarded growth in nominal wages in proportion with labour productivity growth.

The widening gap between wages growth and labour productivity growth has been a world trend (especially in Anglo countries) and I document the consequences of it in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009).

But the attack on living standards has targetted more than the bottom end of the labour market, although the minimum wage workers have certainly been more deprived of the chance to share in national productivity growth than other workers.

The recent FWC decisions provides some relief to that trend.

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (red line), GDP per hour worked (blue line), and the Real Wage Price Index (green line), the latter is a measure of general wage movements in the economy.

The graph is from the June-quarter 2005 up until June-quarter 2024 (indexed at 100 in June 2005 and extrapolated as above out to 2024).

By June 2022, the respective index numbers were 117.6 (GDP per hour worked), 106.6 (Real WPI), and 108.9 (real FMW).

All workers have failed to enjoy a fair share of the national productivity growth. However, the most recent FWC decision has seen the lowest paid workers improve their position relative to other workers.

Like all graphs the picture is sensitive to the sample used. If I had taken the starting point back to the 1980s you would see a very large gap between productivity growth and wages growth, which has been associated with the massive redistribution of real income to profits over the last three decades.

In my view this represents the ultimate failure of capitalism.

Conclusion

The FWC did not follow through on their excellent decision last year, which provided for full cost-of-living adjustment for the minimum wage workers.

However, note the discussion above as to the best purchasing power measure to use.

The latest decision will leave low paid workers worse off in real terms than where they were at the onset of the pandemic.

Of course, the employers were aghast at the decision while at the same time pocketing record profits as a result of their profit gouging.

Fortunately, their greed was mostly rejected by the Commission.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What is your view on Net Zero Migration proposed by Neil Wilson. Stealing skilled doctors from places endemic malaria and rickets is wrong end brain drain. Appeared to be part of UK post war consensus: https://news.sky.com/story/why-farage-getting-his-dream-of-net-zero-migration-would-probably-not-be-a-good-sign-for-the-uk-economy-13147745 “The (possibly surprising) answer is that for much of Britain’s post-war history, it had negative net migration.

For nearly every year from 1947 through to the early 1980s, there were more people emigrating from the country than coming in. This was not seen as a particularly positive story at the time.”

Writing in “The Wealth of Nations”, Adam Smith gave a warning about those who live by profit.

250 years later it is pertinent to the powerful lobbying and propaganda on behalf of big business, and the continual undermining of real wages and denial of a fair share of productivity gains to workers.

Smith concluded Book I with the following apparently timeless observation, aimed principally at the very wealthy and influential merchants and master manufacturers.

“The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public……….The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same as that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even oppress the public, and who accordingly have upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.”

hi, i tried to recreate Bill’s chart (had to index from June 2010 – all the NMW decision data I could get from the FWC) and the chart looks like the real NMW has crossed the GDP per hour worked line since June 2023. Could anyone please tell me what that means (big assumption that I’ve done the chart correctly). Would it mean that workers are now getting better outcomes, or that productivity is just slowing down or something to do with output gaps? Not sure if we can post graphs but the other two lines look pretty much the same as Bill’s when I reindex from June 2010, just with slight changes at the end of the line.

sorry should have mentioned that its Bill’s last chart and also I used CPI as the deflator