The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

RBA is now a rogue organisation and the Government should act to bring it back into check

Yesterday (February 6, 2024), the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) released its so-called – Statement on Monetary Policy – February 2024 – which is a quarterly statement that “sets out the RBA’s assessment of current economic and financial conditions as well as the outlook that the Reserve Bank Board considers in making its interest rate decisions”. It accompanied the latest decision by the RBA, which held the policy target rate constant at 4.25. However, the Governor told the press that they had not ruled out further rate rises despite the inflation rate falling quickly and strong indications that the economy is slowing rapidly. Just yesterday, the ABS released the latest – Retail Trade, Australia – for December 2023, which showed that volume trade is down 1.4 per cent over the last year. In the September-quarter 2022, growth in volume was 9.8 per cent (a sort of pandemic overshoot after the restrictions were eased). By the December-quarter 2023, the volume growth was minus 1 per cent, the third consecutive quarter of negative volume growth. It would be totally outrageous for the RBA to consider further hikes. But it has become a rogue organisation and its statements reveal how deviant its reasoning has become.

On June 20, 2023, the incoming governor of the RBA gave a speech – Achieving Full Employment – Newcastle – where she outlined how the mainstream concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) influences RBA monetary policy decisions.

She claimed that the RBA believed the NAIRU to be 4.5 per cent in Australia at a time that the official unemployment rate had been steady at around 3.5 or 3.6 per cent.

She also said that meant that the RBA had to keep hiking interest rates to force the unemployment rate up to 4.5 per cent (a loss at the time of more than 150,000 jobs) to stabilise inflation.

This was at a time that the inflation rate was just about peaking and would soon decline rather sharply.

I pointed out at the time that the NAIRU couldn’t be 4.5 per cent if the unemployment rate was stable at 3.5 or so per cent and inflation was falling.

I analysed that speech in this blog post – Mainstream logic should conclude the Australian unemployment rate is above the NAIRU not below it as the RBA claims (July 24, 2023).

Soon after, the RBA revised their estimate of the NAIRU down to 4.25 per cent but still the official unemployment rate was well below 4 per cent.

At this time, the inflation rate was continuing to decline, which made a mockery of the RBA’s logic and justifications for the interest rate increases.

The quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy (cited in the Introduction) is more telling of how lost the RBA has become – tied up in its arrogant assertions of mainstream theoretical concepts and then abandoning them when the data defies the ‘theories’.

In the – Press Conference – explaining the monetary policy decision yesterday (February 6, 2024), the Governor admitted that the RBA had no idea of what full employment was (see from the 42 minute mark).

She referred the press gallery to Chapter 4 of the Statement, which provides a detailed discussion – “In Depth – Full Employment”.

They are now claiming that their previous statements of the NAIRU cannot be taken seriously:

Given these limitations, the RBA does not target a fixed level of full employment.

Of course, the RBA Act 1959 requires the RBA to pursue full employment.

So they “maintain a suite of models that provide a range of estimates of spare capacity in the labour market” – which is just ‘general speak’ for the NAIRU estimation.

They write:

The models estimate what labour market outcomes would be consistent with full employment based on historical relationships and economic theory. These models primarily estimate the rate of unemployment or underutilisation that puts neither upward nor downward pressure on inflation or labour cost growth.

In other words, the NAIRU.

They admit that their models and the estimates “around the central estimate” they produce are “subject to considerable uncertainty”.

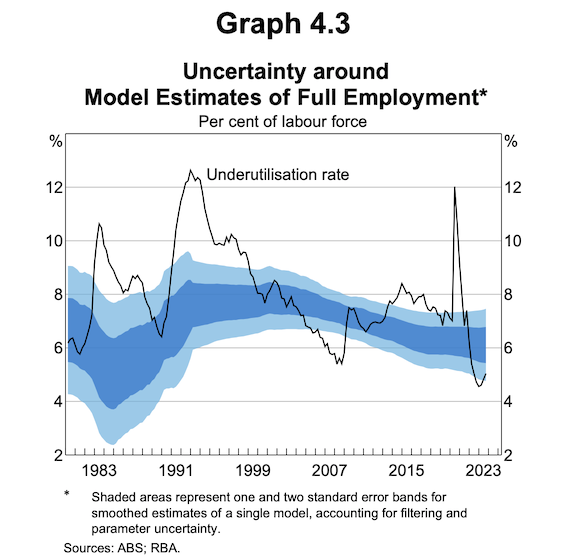

Here is a Graph (4.3) they provide to demonstrate their model estimates.

The solid line is the actual rate of hours-adjusted labour underutilisation – which takes into account official unemployment and underemployment (adjusted for the extra hours that workers would like to work).

I actually think their estimates of labour utilisation is seriously downward biased.

For example, in May 2023 (when detailed hours data was available), there were 1,594.4 thousand underemployed workers.

The ABS reported that around 45 per cent of those workers wanted to work full-time and on average all underemployed workers wanted to work an additional 11 hours per week.

In the same month, there were 520 thousand unemployed workers of which 350 thousand wanted to work full-time.

A rough calculation suggests that this wasted but available labour comprises around 7 per cent of the labour force.

The RBA estimated around then that ‘labour underutilisation’ was around 5 per cent.

Downward biased.

The blue-shaded areas comprise the confidence intervals of their estimates of the NAIRU with the point estimate being middle of the dark blue or inner shaded area.

What do these bands mean?

The widest band is the 95 per cent confidence interval which means that you are equally certain the true rate lies somewhere between the upper and lower bands with a 5 per cent change of error.

So in the current period, the RBA estimate of full employment could be 7.5 per cent underutilisation of labour or 5 per cent.

They would be equally ‘certain’ of both.

Which means for policy making purposes that this exercise is rather pointless.

Why?

Because if the economy was operating above ‘full employment’ then any inflationary pressures would be a sign of excess demand.

But how would they decide that?

What if the actual underutilisation was at 7 per cent which would be well above the lower band of their estimate range?

Should they tighten policy (ignoring whether tightening monetary policy works or not)?

They would conclude no.

But then if they used the upper band limit their answer would be yes.

So this sort of exercise provides no real guidance at all and is largely smoke and mirrors.

The problem would have been even more pronounced in the 1980s, when their error bands were much wider – for example, they could not have discerned that full employment was around 2.3 per cent or close to 8 per cent around 1984.

The Statement said that:

Given the substantial uncertainty involved with each of the model estimates, it is possible that labour market conditions are already consistent with full employment, but the probability is relatively modest.

In the press conference, the Governor indicated that the current unemployment rate of 3.9 per cent was no longer seen as an issue, despite her claims last year that the unemployment rate had to rise to 4.5 per cent to stabilise inflation.

The point is that the RBA is now a rogue organisation that previously pretended to be making decisions based on economic concepts such as the NAIRU but after that logic has been exposed by the facts now admits it no longer has any precision around these concepts.

However, based on its own forecasts, it is suggesting that inflation will enter its targetting range (2-3 per cent) in December 2025, whence the official unemployment rate is forecast to be 4.4 per cent.

That is an additional 130,000 jobs would be lost (relative to December 2023) if the RBA is correct.

But the point here is that this must be their NAIRU forecast as well because according to their logic full employment is defined as the unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation.

Those 130 thousand jobs are real people.

The smug governor can laugh her head off at press conferences (if you watched it) and pretend to be thoughtful and analytical but the RBA is pursuing a policy approach that will deal at least 130 thousand people unemployed when they admitted to the press yesterday that they really have no idea of what the unemployment rate consistent with full employment is.

That is a disgrace in my view.

Conclusion

The RBA also acknowledged that the proportion that debt holders are now devoting to interest repayments as a result of their interest rate hikes has skyrocketed and is by any measure unsustainable for a growing number of citizens.

The RBA also hasn’t a clear idea of the lagged effects of their previous interest rate decisions, yet are threatening more.

And when you think about it, the most recent (monthly) inflation rate estimate from the ABS suggested the annual rate has fallen to 3.4 per cent (and falling sharply), it seems disingenuous in the extreme to be further threatening people with more rate rises.

Especially when their statements are revealing that the RBA has no coherent logic that stands empirical scrutiny.

As I have said previously, the Governor’s salary should be inversely tied to the unemployment rate and then the threats would diminish I would guess.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Central bank independence from public scrutiny would, sooner or later, come down to this.

With the exception of the JCB, all others CB in the western world follow the fed.

Which tells us that there is no independence whatsoever.

They’re very much dependent.

The only doubt is whom they depend on.

Governments find it very convenient to blame the “independent CB” for the (intentional) failures of the policies they fake, so we shouldn’t expect their help.

The French farmers have the answers we need.

I stand by my claim that “independent” central banks are, by design, aristocratic institutions inimical to labour.

Bullock claims that three “facts” reveal that Australian inflation is homegrown and demand-driven: labour underutilisation is low, inflation is broadly-based, and overall inflation is underpinned by services inflation.

Her argument is a non sequitur. The above facts, even if conceded (and I would not concede them), do not indicate that inflation is homegrown and demand-driven.

Hi Bill,

Another great article as per usual. This is unrelated but I was wondering if you could recommend any articles on the effects of interest rates on inflation, and whether there are any empirical links between interest rate rises and lower inflation?

Looking at Australia, it seems that the recent rate rises have actually been passed on to consumers as firms have considerable market power (especially essential goods and services, Woolies etc., along with price gouging). Ultimately I was wondering if current neoclassical theory can point to evidence that justifies interest rate rises as a way of tackling inflation. Hope that makes sense.

Cheers,

Gabe